Babe Ruth became a superstar during the 1920 season. He’d smashed the home run record the year prior with 29 and was traded from the Red Sox to the Yankees after the season. After an inauspicious start to spring training—it took him three weeks to hit a home run and, per SABR, he knocked himself out running into a palm tree in the outfield in Miami—Ruth went on to have the best season of his career. He ended up hitting 54 home runs.

Playing in the biggest city in a booming country, Ruth became a pop culture phenomenon as well. “Right now America is worshipping a 26-year-old lad named Babe Ruth,” a story in The Billings Gazette read. Grantland Rice wrote that Ruth made “normal humans look like Pygmies.” A wire story from the time says New Yorkers went wild over the Bambino, telling tourists to go see Babe Ruth when they visit the city. His wife—always seemingly identified as Mrs. Babe Ruth, as it was the 1920s—got big feature stories about her. Some of the Babe’s nicknames were still being worked out, as the Los Angeles Record called him “the King of the Swat” and the “Emperor of the Swat.” The Red Sox were so embarrassed they tried to spin the signing of Ben Paschal as “the second Babe.” (Paschal would hit only 24 homers in his career, but did become a teammate of Ruth’s on the Yankees in the second half of the decade.) According to one story, Yankees owner Colonel Ruppert was so enthused by a Ruth homer that he smoked his first cigarette in six years.

But Ruth's season almost ended 101 years ago this week. Babe Ruth, driving down Baltimore Pike in suburban Philadelphia, crashed his car in Wawa, Pennsylvania. It flipped, trapping him under the vehicle. Fortunately, he and the car’s other occupants were able to climb out from underneath it. He then had the $5,000 car towed to a garage in Media and told them to sell it.

The Yankees had just finished a 10-game road trip against the Athletics and Washington Senators when Ruth crashed. He’d swatted two homers on the first day of the trip, one in each game of a doubleheader, but didn’t hit any more the rest of the trip. The Washington Times reported that “Rock ’Em Ruth Isn’t Rocking Them” and that his lack of homers on the trip meant "little or no enthusiasm has been stirred by his coming” to D.C.

The Yankees had a day off on July 7. After a 17-0 win against the Senators a day earlier, Ruth planned to drive his wife and three others members of the team—outfielder Frank Gleich, catcher Fred Hofmann, and coach Charles O’Leary—in his “brand new” touring car. They were headed back to New York. This was before the days of the interstate, so by the time he got to Pennsylvania, he was driving on Baltimore Pike—an auto trail that connected Baltimore and Philly. There were about 7.5 million cars and trucks by 1920.

Ruth approached Wawa, Pa.—the eponymous dairy farm existed, but the deli/gas station chain built out of it would not open its first location until 1964—when he approached a curve in the road near the house of Coates Coleman, a Philadelphia tobacconist. Ruth crashed, and the car flipped upside down.

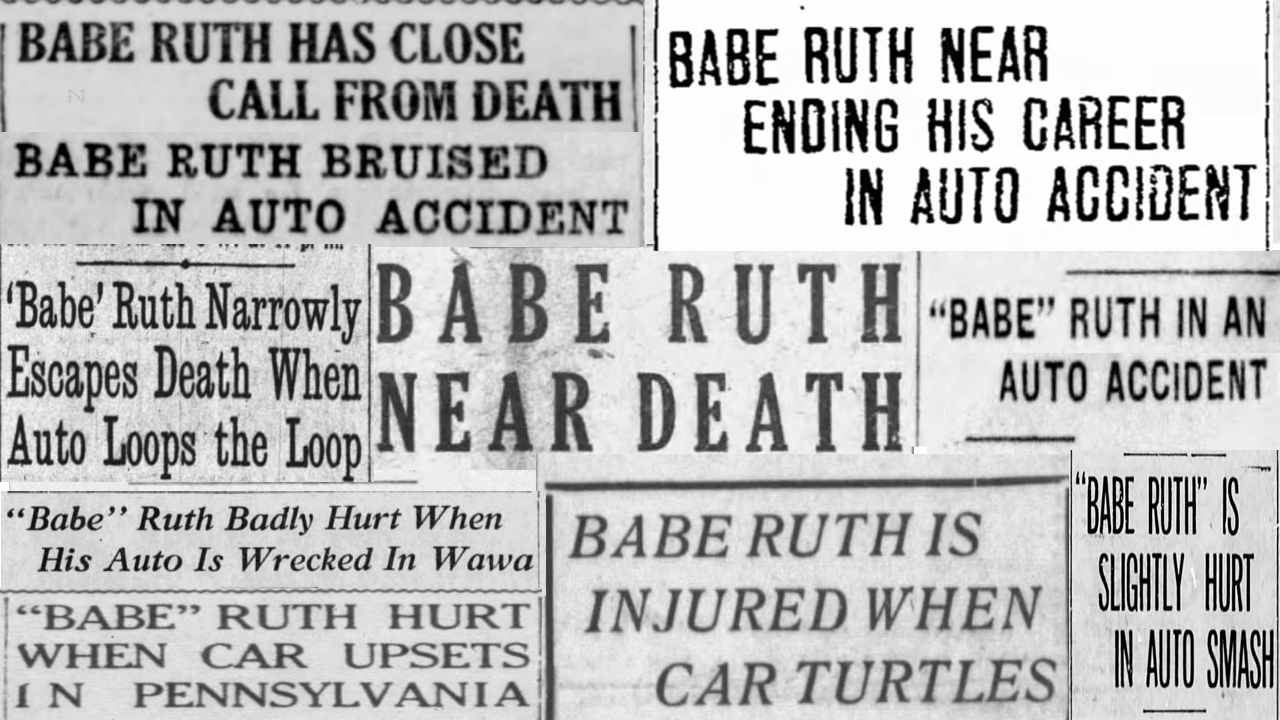

Newspapers around the country reported the accident, often quite differently. Due to old-timey newspaper style, lots of papers called him “‘Babe’ Ruth.” (The Medford Mail Tribune called him “‘Babe Ruth’”, as if his last name were a nickname as well; the Beatrice Daily Sun of Nebraska called him “Big ‘Babe’ Ruth.”) The Fitchburg Sentinel in Massachusetts ran a banner headline: “‘Babe’ Ruth Slightly Hurt As Car Turtles.” (Several outlets used “turtle” to show the car flipped upside down; the Brooklyn Daily Eagle wrote “car turns turtle” in a headline. This century, it seems like only news outlets in India use it.) The Richmond Daily Independent put it in “Late Wire News” on its front page, above a story out of Paris, Texas of two black men being burned at the stake.

Other places did not consider it big news: The Sacramento Star put it in the corner of Page 7, below a story headlined “Elevators To Be Repaired.” The Star called Ruth “unhurt.” Not every newspaper did. The Marion Star said he “escaped serious injury.” The Bismarck Tribune said he was “slightly hurt.” The Lancaster New Era disagreed, saying he was “badly hurt.” The Green Bay Press-Gazette deemed him “bruised.” Omaha Daily Bee: “Hurt.” Arizona Daily Star: “Not hurt.” The Associated Press wire story did deem him “badly hurt about the knee,” with the source of, as they called her, “Mrs. Coates Coleman.” The International News Service, Hearst’s wire, instead said he and the other occupants “escaped serious injury.”

A Ruth biography, Robert Creamer’s 1974 Ruth: The Legend Comes To Life, says a newspaper in Philadelphia reported that Ruth had been killed. I wasn’t able to find that story, and neither was Philadelphia Inquirer writer Frank Fitzpatrick five years ago; that assertion appears in other Ruth biographies but there’s no evidence of it in microfilm archives. One newspaper, The Montgomery Times in Alabama, did run the headline “BABE RUTH NEAR DEATH.” But given that the story said he escaped serious injury, the headline seems to be saying he “cheated” death, much like this headline in The Oregon Daily Journal: “‘Babe’ Ruth Narrowly Escapes Death When Auto Loops the Loop.”

A story in a Philadelphia paper that I was able to find appears in the Evening Daily Ledger the day of the accident. That detailed how the auto flipped over and landed in a clay bank; the paper said the roof being up saved the lives of the passengers in the car. "I was asleep, when the grinding of Ruth's breaks awakened me,” Coates Coleman said. “From the noise I judge he must have been going pretty fast. There is a very bad turn at this point in the pike. Ruth told me afterward that another car had come along and cut in suddenly in front of him, making it necessary for him to throw on his breaks.”

Coleman said two of the players were crawling out from under the car when he reached it. He helped the five passengers escape the vehicle. Some stories make Ruth into the hero: “Ruth, by a Herculean effort,” one report said, "tipped the car sufficiently to permit his wife and the three ball players to crawl out. They in turn lifted the car so Ruth was able to escape.” Ruth and his pals hung at the house until about 5 a.m., when they caught a train passing through Wawa headed for Philadelphia. They then caught a train to New York.

As for the car, the Evening Daily Ledger quoted Ruth directly (probably via Coleman): “Aw, keep it and sell it for what you can get, I’m in a hurry. I'll get a new one when I land in N’Yawk.” A garage owner in nearby Media towed the car away, which cost Ruth $5,000. “Babe struggles along somehow on $20,000 a year,” the paper wrote, proving that the tradition of newspapers complaining about high pro athlete salaries goes back more than a century.

The New York Tribune’s “Sheriff” W.O. McGeehan reported that initial accident reports shook up the Yankees management, “for the Yanks already have the largest sick and convalescent list in organized baseball.” He also reported Ruth as the hero: "If it had been the average brittle ballplayer instead of Ruth, there would have been a fatality. The greater part of the tonneau was wrapped about the neck of the infant swatigy, who arose on his haunches, lifting the car with him and permitting the others to crawl from under.” He ended his column with a cute line: “Colonel Ruppert has issued a general order to the effect that from now on Yankee players are under no circumstances to wear automobile tonneaus as collars, nor are they to let the… engines or other heavy parts of automobiles rest on their necks.”

The Yanks played the Tigers at the Polo Grounds on July 8; Ruth was honored by the Knights of Columbus and went 1-for-4 with a run scored in a 4-3 loss. He homered in the next three games against the Tigers, all Yankees wins. He broke his own home run record on July 19. Clearly, he was not hurt.