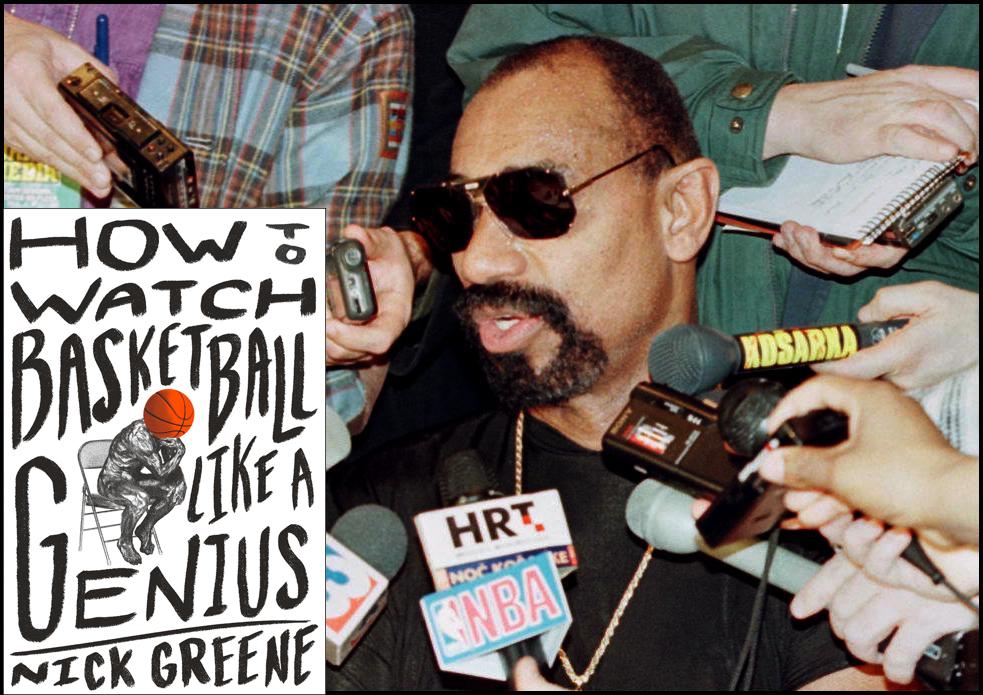

The following is an excerpt from the new book, How to Watch Basketball Like a Genius: What Game Designers, Economists, Ballet Choreographers, and Theoretical Astrophysicists Reveal About the Greatest Game on Earth, by Nick Greene. The book is published by Abrams Press © 2021 and is available for pre-order now.

If it weren’t for eye-witness testimony and a surfeit of concrete documentary evidence, one could make a compelling argument that Wilt Chamberlain didn’t actually exist. His individual statistical achievements look like typos. Or, better yet, like an imaginative prankster snuck into the NBA’s offices and sprinkled this fictional character throughout the league’s record books. Though, if somebody wanted to get away with that kind of jape, they really should have made the records plausible. What this “Wilt Chamberlain” fellow accomplished was anything but.

Chamberlain famously scored 100 points in a single game, but he didn’t think much of that particular record. “A lot of people ask me if that 100-point game was my biggest thrill in sports. Frankly, it isn’t even close to the top,” he wrote. “[A]nyone can get lucky.”

That quote comes from his 1973 autobiography, Wilt: Just Like Any Other 7-Foot Black Millionaire Who Lives Next Door. In it, he writes that, hours before he scored 100 points against the Knicks, he also set the high score on a shooting gallery-style arcade game near the stadium. He seems more impressed with that virtual achievement than the basketball one, and he dedicates about as much space in his book to each feat.

Wilt is a bizarre autobiography. There’s an entire chapter dedicated to the design and construction of his sprawling Los Angeles mansion that suddenly digresses into a lengthy defense of him not offering his dates tickets to see him play. (In regard to environmentalists’ concerns about the use of nose fur from arctic wolves on the playroom furniture: “I’m deeply concerned about the environment, too ... I hadn’t ordered the wolves killed; I just bought the fur after they were already dead.” And, a few paragraphs later, describing his dating strategy: “I’d rather have her appreciate my other skills in a more appropriate setting—ordering dinner in a good restaurant, talking on a sunlit beach, driving in a fine car, making love in a warm bed.”) While chock-full of tales about romantic conquests, this particular book does not include the claim that he slept with 20,000 women during his life. That appears in a later autobiography, 1991’s A View from Above, and it should be noted that he uses some pretty specious math to reach that infamous number.

Chamberlain is a charming and erudite megalomaniac, and if you’ve ever wanted to read hundreds of pages detailing how great he was then this is the book for you. Hell, I’d recommend it to those who don’t care to learn about his glamorous lifestyle and various triumphs—Wilt is still a remarkably entertaining book. He portrays himself as both the main character of mid-century America and a bemused loner who just wants to hang out in his mansion festooned in ethically sourced arctic wolf hair.

Do I think he actually set the record for the fastest single-person transcontinental automobile trip when he drove from New York to Los Angeles in 35 hours and 53 minutes? Maybe? What about his claim that he trounced three Russians at a drinking contest during a state dinner in the Soviet Union, an event that also happened to mark the first time Chamberlain ever drank vodka? I want to believe.

Nonetheless, the thing that I would argue to be his most astonishing achievement is undeniably true, and the record books back it up.

Chamberlain was bored heading into the 1967–68 season. He was also sick of being called selfish, a pejorative that followed him around even more than “loser” did, and so he resolved to do something about both issues. “I’d already proved I could outscore everyone. That was no longer much of a challenge,” he writes. “I’ve always been the kind of person who needs specific, concrete goals and challenges ... so I decided I’d lead the NBA in assists.”

Astonishingly, Wilt did it. He actually did it.

Chamberlain finished the season with 702 assists, 23 more than the runner-up, Hall of Fame point guard Lenny Wilkens. It was the first and only time in history that a center led the NBA in assists. “I probably got more satisfaction out of winning that title than almost any other,” Chamberlain writes.

We hail assist leaders as altruistic paragons of team ball, but Wilt Chamberlain’s triumph was hilariously egocentric. “I remember a few games when I’d tell whoever was hot on my team, ‘Look, I’m just going to pass the ball to you for a while. I keep setting these other guys up, and they keep blowing easy shots. How am I going to beat Wilkens that way?’”

The joy of sharing should be its own reward, but Chamberlain didn’t finish the 1967–68 season leading the league in joy. His year of giving ended in familiar fashion, with his 76ers bowing out of the playoffs at the hands of the Boston Celtics. This defeat was particularly frustrating, as Philadelphia blew a 3–1 series advantage. It was the first time a team had ever endured such a collapse in the postseason.

Chamberlain made a show of being unselfish and attempted only nine field goals during the deciding Game 7, which Philadelphia lost by four points. “In earlier losses to Boston—in other years—I was blamed for shooting too much and not playing team ball. This time, they said I didn’t shoot enough, particularly in the second half, when I didn’t take one shot from the field,” he writes. “But I was playing the way we’d played—and won—all year.”

It’s not that Chamberlain was incapable of self-reflection—he frequently recounts moments of failure throughout Wilt—it’s just that he almost never comes to the conclusion that he was responsible in any way. “Boston had half their team guarding me,” he writes of that Game 7. “That left my teammates open for easy eight-to-ten foot jump shots. I kept passing the ball to them, but they kept missing. Hal [Greer] hit only eight of twenty-five shots. Wali [Jones] hit eight of twenty-two. Matty [Goukas] hit two of ten. Chet [Walker] hit eight of twenty-two. Those four guys took most of our shots, and hit less than a third of them. But I got the blame.”

In his book, Chamberlain says that Chet Walker eventually apologized for that Game 7. The two were on vacation when Walker “got all choked up one day in Stockholm” and told him, “We were wrong.” Wilt seemed to think this apology was the least he could do, writing that “[t]he other guys had blown cinch shots, too, but none of them had come forward to accept the blame for the loss; they’d all let me be the whipping boy.”

If true, that story makes Chet Walker seem like a dream teammate: empathetic, communicative, and willing to accompany you to Sweden after a bad loss. Was the tearful forward actually “wrong” in that situation? According to couples therapist Alicia Muñoz, it doesn’t even matter. She sometimes tells her patients, “You can be right, or you can be in a relationship. You can’t be both, so take your pick.”

Muñoz is the author of a series of relationship guides, including No More Fighting and The Couple's Quiz Book. When I tell her about Chamberlain’s quest for the assists title, she says his approach to performative unselfishness is actually rather common. “Oh my God, it happens all the time. I’ve been guilty of that early in my relationship with my husband as well,” she confesses. It’s the kind of thing that, if left unchecked, can take its toll. “The idea is that there really is no sacrifice in relationships, and you’re not manipulating a situation, you’re not trying to check the boxes, you’re not trying to get kudos from your partner. You’re not saying, ‘Well, I did everything you asked, why are you still unhappy? Why are you still complaining?’ A lot of times we—not just as couples but as human beings—have this innate sense of egotism and self-focus and self-centeredness.”

That is not to say that being in a relationship requires acquiescent servitude. Quite the contrary. The term Muñoz uses is “enlightened self-interest,” which is the ability to understand that the individual shares the success of the collective. “Even if you may not be the superstar, whatever you do in support of your team or whatever you do in support of your relationship is actually enlightened self-interest,” she says. “That team is your home. It’s a network of connectivity. Whatever I do that serves you and supports you truly is my best bet at success.”

I worry that comparing romantic relationships to a basketball team is a bit of an oversimplification, but Muñoz assures me they share plenty in common. “Many of the troubles and conflicts and struggles that couples get into are about a lack of teamwork—a lack of alliance, or a sense that there are two me’s versus a we. Not only being a team, but feeling like a team. Figuring out what makes each person feel like they are in a true alliance is critical.”

I’m not sure that Wilt Chamberlain, by virtue of the fact that he was Wilt Chamberlain, could ever stop thinking about Wilt Chamberlain. He possessed just about the precise physical specifications one needs to dominate Naismith’s game, and this random bit of genetic happenstance ensured that he would lead a completely singular life full of fame and expectation. “I feel that stardom and fame really reinforce a lot of the negative aspects of our minds and our egos,” Muñoz says. “You don’t have that with normal couples so much.”

When he enrolled at the University of Kansas, Chamberlain says that Phog Allen, the school’s legendary head coach, told everyone, “Wilt Chamberlain’s the greatest basketball player I ever saw. With him, we’ll never lose a game; we could win the national championship with Wilt, two sorority girls and two Phi Beta Kappas.” During his sophomore year, famed columnist Jimmy Breslin wrote an article, titled, “Can Basketball Survive Chamberlain?” He essentially was a fictional character in people’s eyes, but this Paul Bunyan needed more than just a blue ox to get by. Chamberlain never won a national championship at Kansas. Basketball did, in fact, survive his existence.

As he laments in his autobiography, “Even Wilt can’t do it alone.”