Welcome to Sports Stories, a publication at the intersection of sports and history: written by Eric Nusbaum, illustrated by Adam Villacin, and delivered to your inbox every Tuesday. If you’re not already a subscriber, please sign up here.

“Perfection belongs to narrated events, not to those we live.”

Those are the words of Primo Levi, a writer I admire a great deal. Primo Levi survived Auschwitz and wrote about it in a number of books. These particular words are from his book The Periodic Table.

On its face, the thought seems almost too obvious to be profound. Levi was writing about his desire to look into the eyes of one of his tormentors, and about the insufficiency of general “we’re sorry” type repentance he heard a lot of from Germans after the war.

But Levi’s words also get at something true about all historical writing, all nonfiction. As the narrators of ostensibly true stories, we can invent a sort of perfection: arcs and tension and drama. We can make beginnings and middles and endings feel inevitable. But in the present tense of a life, we are denied that logic. It’s always messy.

There is a perfect version of Victor “Young” Perez’s life. There is version that fits neatly into the archetypes of sports writing. The rise of a champion from obscure origins and the tragic, inevitable fall.

But then there is Auschwitz.

Victor Perez was born in Tunis in 1911. By the time of his birth, Tunisia had been a French colony for thirty years, which of course was but a blip in the long history of the land that had once been the site of Carthage. Empires come and empires go.

Situated on the edge of a wide Mediterranean bay, Tunis was a bustling, diverse, international city. Among other groups, Tunis was home to a sizable and fairly well-assimilated Jewish population to which the Perez family belonged. The Perez family would have spoken French at home, in addition to a dialect known as Judeo-Tunisian Arabic.

The family was poor. Victor and his siblings scrounged to get by. Victor would get into street fights and steal oranges from the marketplace and tag along with his older brother Benjamin, who had become obsessed with boxing. There was a light heavyweight champ at the time named Louis Mbarick Fall, better known to his admirers as The Battling Siki. Siki was from Senegal, which was also under French rule, and he captured the imagination of the Perez boys. It was possible, they saw, to make it from the streets of an African city to international renown.

Unlike the Battling Siki, who fought against famed bruisers like Georges Carpentier, the Perez boys were small and fast. They were flyweights through and through. Benjamin Perez picked up the nickname “Kid.” And Victor, a few years later, became known as “Young.” They both turned pro: first Benjamin in 1925, then Victor in 1928.

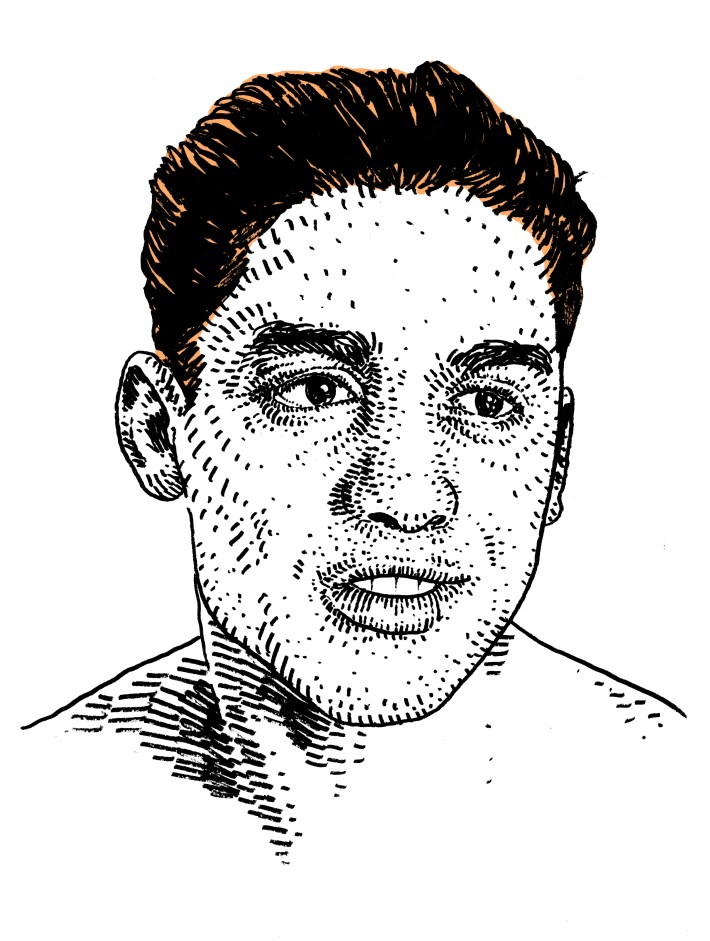

Benjamin was a fine talent, but Victor—Victor was something special. He was only 5-foot-1 but he was a powerful puncher and had the kind of looks that boxing promoters dream of. He debuted as a pro at just 16. Less than a year later, he was recruited by a French manager to come to Paris and try his hand there.

The rise of Young Perez had a mythical quality. He was one of those people who took naturally to stardom. He won fight after fight, wearing a star of David on his trunks in the ring, and elegant tailored suits outside of it. He became an instant idol amongst Tunisians, amongst Jews, amongst the French, and ultimately across all Europe. In 1931, Perez knocked out the great American flyweight Frank Genaro to become the world’s undisputed champion. He was only 20 years old.

His face was on candy wrappers. He returned to Tunis a hero, his ship greeted by thousands of wellwishers at the port. He dated a French movie star named Mireille Balin. She would pick him up at the gym in his car, an American-made convertible. They were all over each other, the statuesque French actress, and the tiny Tunisian Jewish boxer.

But none of it was meant to last. Perez spent his money as quickly as he made it. The rest he gave away to friends and mooches and whoever else. He lost a couple of big fights in a row: First he dropped his title to American flyweight Jackie Brown. Then, after moving up a weight class, he was knocked out by the legendary bantamweight Panama Al Brown. He was still Young Perez—still beloved by his fans, still proud, still deceptively powerful. But that wasn’t enough to make him a champion again.

Instead, Perez became something of a journeyman. He trained young fighters at a gym in Paris called the Alhambra. He fought across Europe and Africa: in Barcelona, in Manchester, in Cairo. Sometimes winning, sometimes losing. He tried to ignore the news reports about Germany. He even fought there in 1938, falling on points to an Austrian boxer named Ernst Weiss.

As the Nazis neared Paris, Perez’s older brother Benjamin tried to convince him to return with him to Tunisia. But he rejected the idea. He wasn’t built to see the worst-case scenario. Benjamin went back alone and Victor remained in Paris. He fought twice in Occupied France in the summer of 1941. The following year, Hitler ordered Jews in Paris to sew a yellow star on the left side of their coats. Young Perez, who had once proudly worn the star on his boxing trunks, refused to do so.

In 1943, Perez was denounced by some mysterious acquaintance. He had been a world champion. He had been famous. It could have been anybody. Perez was sent first to an internment camp in Drancy, France, then on a convoy to Auschwitz.

A few years ago, an Israeli-French actor named Tomer Sisley made a documentary about Perez called Searching for Victor “Young” Perez. One of the people he spoke to was a survivor named Charles Palant. Palant had been on the same convoy from Drancy as Perez. He had recognized him instantly.

Palant described the cold morning when their train arrived at Auschwitz. He described the sorting process: the prisoners walking forward and the SS officer deciding their fates, declaring seemingly at random whether they should go left, right, left, right. There were exactly 1,000 people on the convoy, records show. 240 were sent to a subcamp called Auschwitz III, also known as Monowitz. The other 760 were never seen again.

Perez and Palant were both sent to Monowitz. Their numbers were tattooed on their arms. They were stripped naked and shaved and humiliated. Did the heights that Perez had once reached make this exercise somehow even more painful for him? Did it rob him of something that even his fellow prisoners didn’t have? They were all human beings. They were all losing something.

Palant said that Perez’s mere presence in the camp gave his fellow prisoners something meaningful to hold onto. “Everybody who was famous linked us to our lives before.”

Perez’s celebrity was not lost on the Germans either. Monowitz was essentially a slave labor camp. Prisoners toiled in factories making rubber products for the I.G. Farben company. Many died from the cold or disease or overwork. The camp was commanded by an SS officer named Heinrich Schwarz.

One of Schwarz’s quirks, or diversions, was that he was an obsessive fan of boxing. On Sundays, he would hold outdoor matches between inmates in the camp’s main square. The boxers of Auschwitz were given more manageable jobs, an extra portion of soup, and a half-day off each week to train in a boxing gym that Schwarz had outfitted in one of the barracks. Perez was one of these boxers.

“Knowing they had a toy called a world champion gave them ideas,” said Palant. “They didn’t rush him to his death. They thought, ‘What can we do with him in a concentration camp?’”

Perez worked in the kitchen. Just as he did when he was a boy stealing oranges from the marketplace, he snuck food out for his friends. One of the other boxers at Monowitz was a teenager named Noah Klieger. Klieger had never boxed before, but lied to an SS officer about it, hoping it might help him survive. Perez trained him and helped him pass as a real fighter.

The other boxers were from Central and Eastern Europe. Perez and Klieger were the only ones in the group who spoke French. They became close. Klieger remembered Perez sneaking pots of soup out from the kitchen every night and serving his friends through a side door. He remembered asking Perez why he did it, when getting caught would have meant being hanged in front of the entire camp.

“A man can’t live on his own,” Perez told him. “He lives to help others.”

This was how Young Perez survived in Monowitz. He boxed. He stole. His job in the kitchen ensured that he had enough to eat. In January of 1945, the Auschwitz camps were evacuated overnight by the SS. More than a million people had been murdered there during the war. Less than 60,000 remained. The prisoners, malnourished and underdressed, were forced to walk for days and days through the snow as Soviet troops approached from the east. The war would soon be over.

At some point, early in what became known as the Auschwitz Death March, Perez came into the possession of a bag of bread. This was a precious thing. Starved, frozen Jews were laying down and dying in the snow by the thousands. As Klieger remembered it, Perez was trying to bring the bread to some of his friends when an SS guard spotted him, armed his machine gun, and shot him in the back.

“He wasn’t just a world champion,” said Klieger in the film. “He was a really great man.” Then he paused, and shrugged.

“What can you do?”

In Tunis, Benjamin Perez and the rest of the family waited for word from Young. They knew, deep down, what had likely happened. Then in 1947, a survivor knocked on their door. He had come all the way from Canada to thank them, to tell them that Young Perez had saved his life in Auschwitz. This was when they knew for sure that he was dead.

Soon afterward, Benjamin Perez traveled to Germany to look for his brother’s body. His brother who had refused to come back to Tunisia. His brother who had become world champion. Perhaps Young’s body had been discovered after the snow melted away. Perhaps he had been buried in some small town after the war. Benjamin searched for months, but he never found his little brother. Once again, he returned to Tunis alone.