Not to mount a horribly marketized argument about something so fascinating, but when there is both sufficient incentive to break the rules and safe opportunity to do so, in any sort of competition, people will cheat. The object in a competitive framework is winning, not process for process's sake or anything as subjective as "fair play," and oftentimes, the simplest way to adhere to the Edwardian theory is to cut corners. This can take many forms: deflating footballs, huffing strychnine, putting a hidden motor in your bicycle, or rigging $7 million worth of children's charity raffles over a six-year period to fund your lavish lifestyle.

Chess, a 1-v-1 regicide-themed tactics board game with an only recently displaced reputation as a banal pastime for boring gentlemen, is no exception. Because it is a physically simple and mentally intricate game, chess is insulated from a variety of the more outré cheating methodologies. Nobody is going to de-inflate their opponent's queen or guzzle illicit steroids, since the game has no physical element. But that doesn't mean the history of chess is any less riddled with scandals and cheaters. On the contrary, the history of chess is inextricable from the history of cheating in chess. Cheating is much easier now than it used to be, and since a cheating scandal at the highest level of the game has ignited into a genuinely global news story, it seems useful to contextualize the Hans Niemann vs. Magnus Carlsen imbroglio within chess's rich, outrageous lore, and also explain the mechanics of how it works. Some methods of cheating—making illegal moves, agreeing to draw or lose to an opponent to manipulate a bracket—are boring. Almost all the other methods of cheating are interesting.

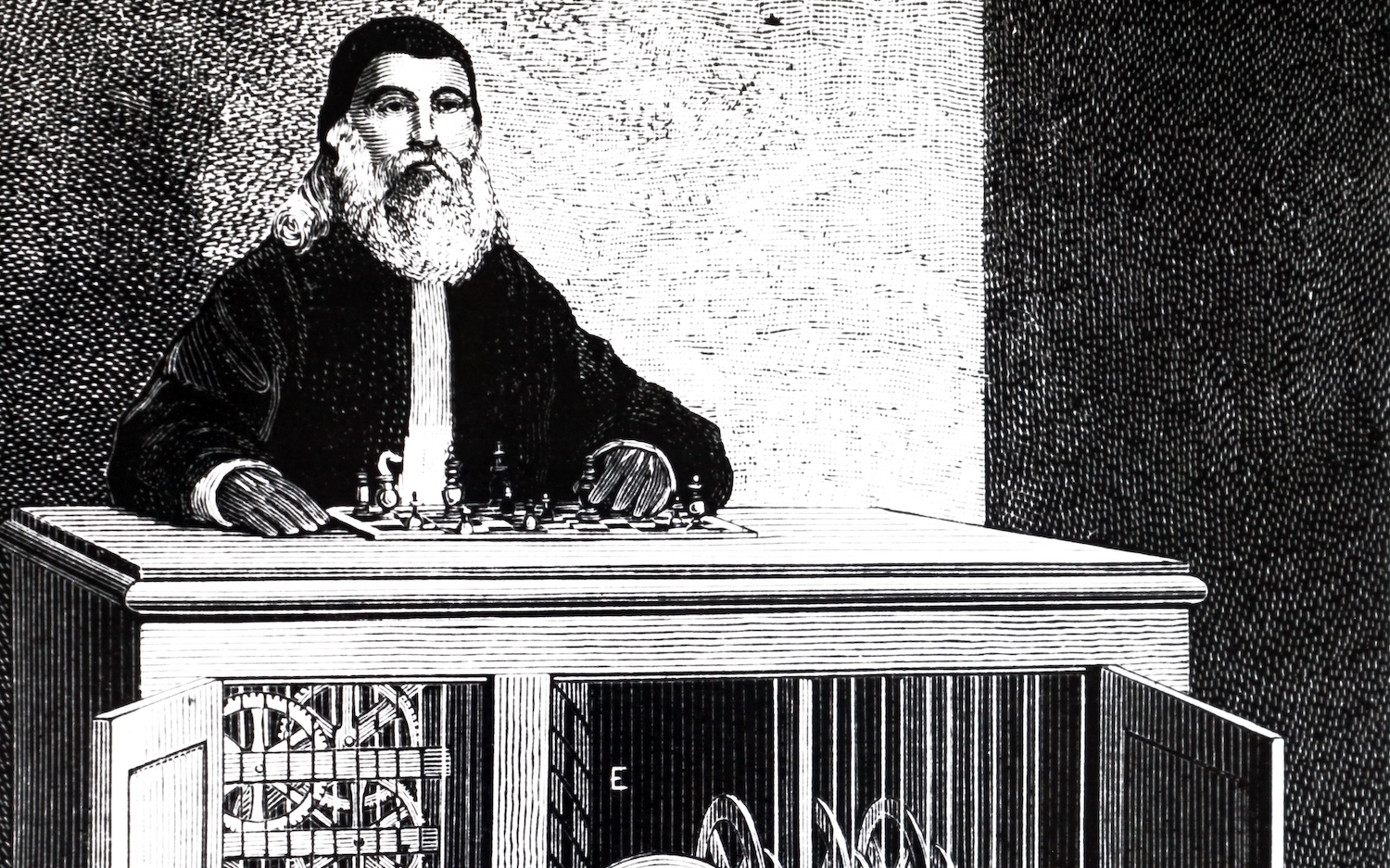

Chess is not deterministic, and positions on the board necessarily require inputs from both people. There are no decks to be rigged or dice to be loaded. Pre-computer cheating, then, was bound up in charlatanry. It was more like magic, where today's cheating is more like surgery, aligning with the evolution from paintbrush to film camera that Walter Benjamin laid out in 1936. Here is the story of the Mechanical Turk.

The Automaton

In 1770, Austria-Hungary's court scientist Wolfgang von Kempelen announced a new bit of court science: a chess automaton. At this point in the 18th century, automata were quite popular throughout Europe. Von Kempelen's was not atypical in design—his simulacrum of the human form was made to resemble a stereotypical Turkish man, which thus earned it the famous moniker of the Mechanical Turk—but for the chess board atop its surface, in front of the robot. The Austrian scientist showed it off in court, assured everyone that the cabinet below the Turk was empty, and set a game up on the board. Some clown from Empress Maria Theresa's court agreed to play, and his ass got smoked. Thus the legend was born.

The Mechanical Turk set out on a world tour, "hanging out" at the prominent Parisian chess salon Voltaire and Rousseau spent time at, playing and beating Benjamin Franklin and Napoleon Bonaparte, and narrowly losing to Philidor, who claimed that the machine possessed a genuine intelligence. Wrong. Humans needed another few hundred years to invent a machine capable of surpassing them. Oliver Roeder, in the chess chapter of his fantastic book Seven Games, explains how the Mechanical Turk functioned:

The Turk was a fraud, of course, though a mechanically impressive one. Over the decades, the device concealed a series of human chess masters inside a small, well-hidden compartment. [...] The operator held a small chessboard f his own, which was connected to a sophisticated mechanism that controlled the movements of the Turk's arm, and a knob, which clenched its fingers. And there were magnets involved. They sat under the public board connected to metal disks, and the secret operator watched these to see when and where the Turk's opponent had moved. The identity of the secret original operator is unknown.

Roeder, p. 64-65

The legacy of the Mechanical Turk, as Roeder lays out, is pretty staggering. Its intricacies and deceptions helped inspire Edgar Allen Poe to write about spooky, mysterious things, and its mechanical ingenuity was an early inspiration for Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace, two of the founders of what is now computing.

The Infamous Polgar-Kasparov Incident Of 1994

Two hundred years later, Garry Kasparov was near the peak of his powers. Kasparov had broken with FIDE, though he continued to win what everyone agreed were legitimate world championships, and he was halfway through a 21-year-reign as the No. 1 player in the world. He had also not yet lost to Deep Blue, who is a computer/demon that IBM constructed with the express purpose of showing that machines could defeat humans in chess. Kasparov would lose occasionally, but he was winning most tournaments he entered. His best chess was still ahead of him, somehow.

Anyway, 1994: a then-17-year-old Judit Polgar made her big-time tournament debut at the Linares International, one of the biggest tournaments in the world. The participants in the 1994 edition had the highest average ELO of any chess tournament to date, and the field included five past, present, or future world champions. Polgar got crushed, finishing 13th. However, the tournament is most notable not for anyone's particular performance, but for an incident that took place between Polgar and Kasparov in their fifth-round meeting. On Kasparov's 36th move of the game, as he was seeking to convert his one-pawn advantage and positional edge into a win, he appeared to make a poor move, advancing his knight to c5. After holding the knight in position, with Polgar staring him down, Kasparov faltered for the briefest of moments, fluttering his hand off of the knight before coming to his senses and making the correct move (knight to d2).

Kasparov violated what is known as the "touch rule." Once you lift your hand off of a piece, it has been legally played. To move it to a different square after after would be to illegally travel back in time, and the rules of some chess tournaments even stipulate that you must play a piece once you touch it. Did Kasparov cheat here? Indisputably. Whether he meant to or not, he attempted some takesies-backsies at a time when he should not have been permitted to do so. Polgar didn't immediately challenge Kasparov's move, which is probably why he was allowed to keep playing, and by the time she said something a day later, it was too late. Polgar confronted Kasparov in person for cheating to beat her, and asked, "How could you do this to me?" The Russian champion became extremely irritated. "She just publicly said I was cheating," he said. "I think a girl of her age should be taught some good manners before making such statements." This was not the first dismissively sexist thing he had said about Polgar, probably the greatest woman to ever play chess. When she first began making a name for herself by beating some of the best men's players in the world, Kasparov called her a "circus puppet," and said she should stick to having children. She beat him in a rapid tournament in 2002, using a line Kasparov himself had once played at a high level.

Computer Time

A good deal of the early history of computing is tied to chess, from Babbage and Lovelace's interest in the Mechanical Turk to Alan Turing's creation of the program capable of making correct decisions through an entire game. While the Mechanical Turk was a phony, legitimate chess robots are over 100 years old. Spanish inventor Leonardo Torres y Quevedo, most famous for inventing the aero car that runs suspended over Niagara Falls, also built the first functioning chess automaton, a robot called El Ajedrecista (the chess player) that could produce checkmates in three-piece endgames with a king and rook against another king. He did all that in 1912, which is impressive even if it only involved three pieces. I personally have bungled three-piece endgames, so it's not like Torres y Quevedo was inventing a machine that could answer something as simple as three nesting binary questions.

Since then, things have obviously come a long way, to the point that no human has a chance to do anything but salvage a draw against the best chess engines. You can download Stockfish right now, boot up Chess.com, and cheat to win as many games as you want, until you get caught and I end up writing about you on Defector. Given any position, Stockfish (or better yet, the new hot robot, AlphaZero) will instantly spit out the most optimal move. Stockfish is an open-source engine built with iterative human input. It calculates, checks the historical record, and makes moves that, though played by a computer, are the result of a string of human decisions. AlphaZero, on the other hand, is an outrageously well-tuned learning algorithm applied to the rules of chess. Its creators claimed it surpassed Stockfish within four hours of blinking into existence. Again, here's Roeder:

It didn't play like a human, with a human's intuitive grasp of strategy. Nor did it play like a computer, with a machine's cold mastery of tactics and its deep calculation. Rather, it played the chess of some other species entirely. Demis Hassabis, a former chess prodigy and one of Deep Mind's cofounders, says it plays in a way that is "almost alien."

Roeder, p. 87

AlphaZero is not available to the public, but the point here is that anyone with an internet connection can, within seconds, learn the correct move to play in any chess position to a degree of certainty our meaty human brains cannot come close to guaranteeing. Thus, almost all forms of modern cheating are all about finding novel ways to do essentially the same thing: put positions into a computer, execute the move recommended by the computer, and do both without getting caught. When people are caught, it is usually because they are doing something suspicious. When Magnus Carlsen made his accusation against Hans Niemann, he noted, "[T]hroughout our game in the Sinquefield Cup I had the impression that [Niemann] wasn’t tense or even fully concentrating on the game in critical positions." The best players in the world calculate impossibly complex lines and consider as much of the spectrum of possibility that they can before making a move, especially in classical chess. If someone makes moves quickly, especially if they turn out to be brilliant moves, it naturally draws suspicion. The higher the level then, the more difficult it is to cheat.

Here are some notable examples, in no particular order, chosen for their novel methods, occurrences at the highest levels of play, or uses of the phrase "PIPI in your pampers":

- Boris Ivanov: In 2012, a 25-year-old Bulgarian named Boris burst onto the scene and strung together a series of impressive games. When asked how he had improved so rapidly, he said, "Chess is my passion. Every day I practice three to four hours at the board. I have no girlfriend. I play brilliantly because I have good training, that is the answer." The chess world was instantly skeptical. An American computer science professor ran the numbers and determined that Ivanov's performance had a million-to-one chance of being legitimate. Several players refused to play Ivanov, and in 2013, Maxim Dlugy noticed something up with his feet. "He walks in a very funny gait," he said, "like he is afraid to step on a part of his shoe." Dlugy showed feet and challenged Ivanov to do the same. He refused. The Bulgarian was caught months later hiding a device in his jacket. Dlugy has been banned from Chess.com multiple times for cheating in online tournaments.

- PIPI: The Armenia Eagles scored an upset win in the 2020 Chess.com Pro Chess League Championships, led by a strong performance from grandmaster Tigran Petrosian. American grandmaster Wesley So insinuated that Petrosian had been cheating, and many noticed that he had an odd habit of looking down, away from his webcam, before he played any moves. Petrosian was banned for life from Chess.com shortly after the tournament, and while nobody has revealed exactly how Petrosian was cheating, that's less relevant than what he said once he was accused.

GM Tigran Petrosian responds to Wesley So's cheating allegations 🍿 PIPI IN YOUR PAMPERS!!!! pic.twitter.com/VuVuUukIoc

— NoJoke (@NoJokeChris) October 1, 2020

- Stockpiss: The single most common method of cheating in over-the-board tournaments is hiding a phone in the bathroom, and sneaking in to get some hints from the computer during bathroom breaks. Like Dlugy, Petrosian once helped catch a cheater using this method, when he caught a Georgian grandmaster using a secret phone to cheat against him in 2015. There have been hundreds of such incidents, at every level of the game. If you ask me, players should simply not be allowed to take bathroom breaks in such a way that allows them to access forbidden knowledge. If I was organizing a chess tournament and wanted to prevent cheating, I would not allow anyone to use the bathroom at all.

- Hauchard, Feller, and Marzolo: Notable for its sophistication and brazenness, the French player Sébastien Feller was caught cheating at the 2010 Chess Olympiad and banned for two years and nine months for an elaborate scheme that involved teammate Cyril Marzolo and coach Arnaud Hauchard. As Feller was playing, Hauchard would relay the positions to Marzolo, who was at home. Marzolo would then check the engine, get the move, and relay it back to Hauchard. Hauchard would then position himself in certain places to communicate certain information to Feller. The table he stood next to indicated the relevant file, and his orientation relative to the table indicated which piece Hauchard wanted Feller to play. Marzolo got the whole crew caught because his phone went off while he was visiting French Chess Federation vice president Joanna Pomian at her home. It was a text, from Hauchard, reading filer les coups sur le portable—"send moves on the cell." That is as unsubtle as it gets.

The Hans Niemann Question

This brings us back to where we started: How could Hans Niemann have cheated? I would like to be clear here that I am not accusing Hans Niemann of cheating, and I've found the virality of the entirely speculative, Elon Musk-driven anal beads theory to be a bit exhausting. A commenter watching the streamer ChessBrah floated it as a clear joke, and its salaciousness has pushed this story into a distinct tier of weird national news.

That is not to say it's logically incoherent, as theories go. Before his match with Alireza Firouzja, after Magnus Carlsen had withdrawn from the Sinquefield Cup, Niemann was subject to an extensive, 90-second metal detection scan. He didn't take any bathroom breaks during his game with Carlsen, and he didn't fidget with his feet. If he was receiving information, it was via a small, well-hidden device of some kind. A player of Niemann's level would not need a very granular level of information to be able to cheat. A grandmaster already sees the board and the interlocking possibilities with clarity and tactical nous. Presumably, the best move in any given position is not a completely counterintuitive sacrifice or something equally boneheaded, and can therefore be hinted at without needing to communicate something as fully formed as "knight e6 check." If a player sees the game at an extremely high level and is told the file, or the rank, or even the side of the board, they will probably be able to determine the correct move for the correct piece. The anal bead theory, while outlandish on its face, at least does correctly hint that a player of Niemann's caliber would only need a small amount of information to play brilliant moves, in sequence, against the best players in the world.

Contextualized within the history of cheating in chess, the Niemann-Carlsen affair is probably going to remain in frustrating stalemate (chess metaphor) for a while. When cheaters are caught, it tends to be because of a flukey piece of luck or because their ill-gotten success becomes too outrageous to ignore. There's something alluring about the mystery at the heart of this story, simply because legitimate chess at the very highest level, played perfectly between two evenly matched geniuses, will necessarily equal or at least approach chess informed by computers. It is almost Icarian. Fake chess is often more beautiful than real chess, too spatially sophisticated and furnished by too fine a degree of forethought to be the product of a human mind. Chess fans are drawn to the game presumably to witness brilliance, which is why cheating in chess is necessarily so fascinating.