I spent the majority of this year in the headspace of Moby-Dick.

The sea! God! Language! Horror! Sperm! A good portion of whoever and whatever I was in 2023 kept thinking about such things throughout. In many ways, 2022 was a bad reading year for me. I don’t give much credence to counting towards a numbered goal, or rating books, though I do have an ever-growing list of titles on my phone that I’d like to get to. But my attention was particularly aimless last year. I spent a good chunk of time with Gene Wolfe and his Book of the New Sun series; it was time well-spent, and so notable that most everything else felt a little stale by comparison. These slumps happen, the ebb and flow of enthusiasm, the indecipherable “I don’t know, maybe?” of picking up a book and putting it back down again, the feeling that I’ve read my last book forever.

Moby-Dick was not on my list. Before January, my only concrete memory of the novel, or its pop cultural significance beyond the requisite comparisons of various tyrannical assholes to Captain Ahab and chasing one’s proverbial “white whale,” was a short sequence in the forgotten 1994 children’s movie, The Pagemaster. Through a combination of live-action and hand-drawn animation, the film follows Macaulay Culkin’s Richard Tyler, an uptight nerd who is terrified of life and only finds solace in statistics. One day, during a driving storm, Tyler seeks refuge in a library where Christopher Lloyd’s Mr. Dewey persuades the boy to get a library card and find a special book. Tyler goes deeper and deeper into the building, eventually tumbling into an animated world of anthropomorphic books and stories, one of which includes a truncated version of the climatic scene in Moby-Dick where Ahab finally catches up to the whale and meets his inevitable fate. So I knew about that part.

I bought Moby-Dick late last year, a tome of infinitely variable historical and literary consequence by an author whose work I had never engaged with. One hears about Herman Melville the way one hears about Leonardo da Vinci or Jesus or Shakespeare. One hears about a man from a very long time ago, known popularly for a specific event or artwork that has been entirely subsumed within the cultural consciousness, whose reputation is cemented as important but still contested as vital. One hears about a man who, through his sheer ingenuity or genius or singularity, remade the world. Still, “big whale” summed it up for me for most of my life. Of course, the whale is not even half of what’s really going on here.

“With finger pointed and eye levelled at the Pequod, the beggar-like stranger stood a moment, as if in a troubled reverie; then starting a little, turned and said:– ‘Ye’ve shipped, have ye? Names down on the papers? Well, well, what’s signed, is signed; and what’s to be, will be; and then again, perhaps it won’t be, after all.’”

Moby-Dick begins with a long section of extracts from works of literature that mention whales: Paradise Lost, the Bible, the logs of captains throughout history, Darwin, “Thomas Jefferson’s whale memorial to the French minister in 1778.” I did not know a single thing about the novel before starting it, and knew it at all only as a received cultural object that was too long, too digressive, too weird for some, and absolutely perfect in every way to others. Before you get to Ishmael or Ahab or the open ocean, you barrel headfirst through a selective yet sprawling history of seemingly every human encounter with the species heretofore known as Leviathan. One of Melville’s most enduring strengths is his method of capturing the simultaneously mythical and lackluster realities of nature. Throughout Moby-Dick, Ishmael narrates humanity’s relationship with the whale, a creature that inspires awe and disgust and no shortage of searching, pseudoscientific conjecture.

“And how nobly it raises our conceit of the mighty, misty monster, to behold him solemnly sailing through a calm tropical sea; his vast, mild head overhung by a canopy of vapor, engendered by his incommunicable contemplations, and that vapor—as you will sometimes see it—glorified by a rainbow, as if Heaven itself had put its seal upon his thoughts.”

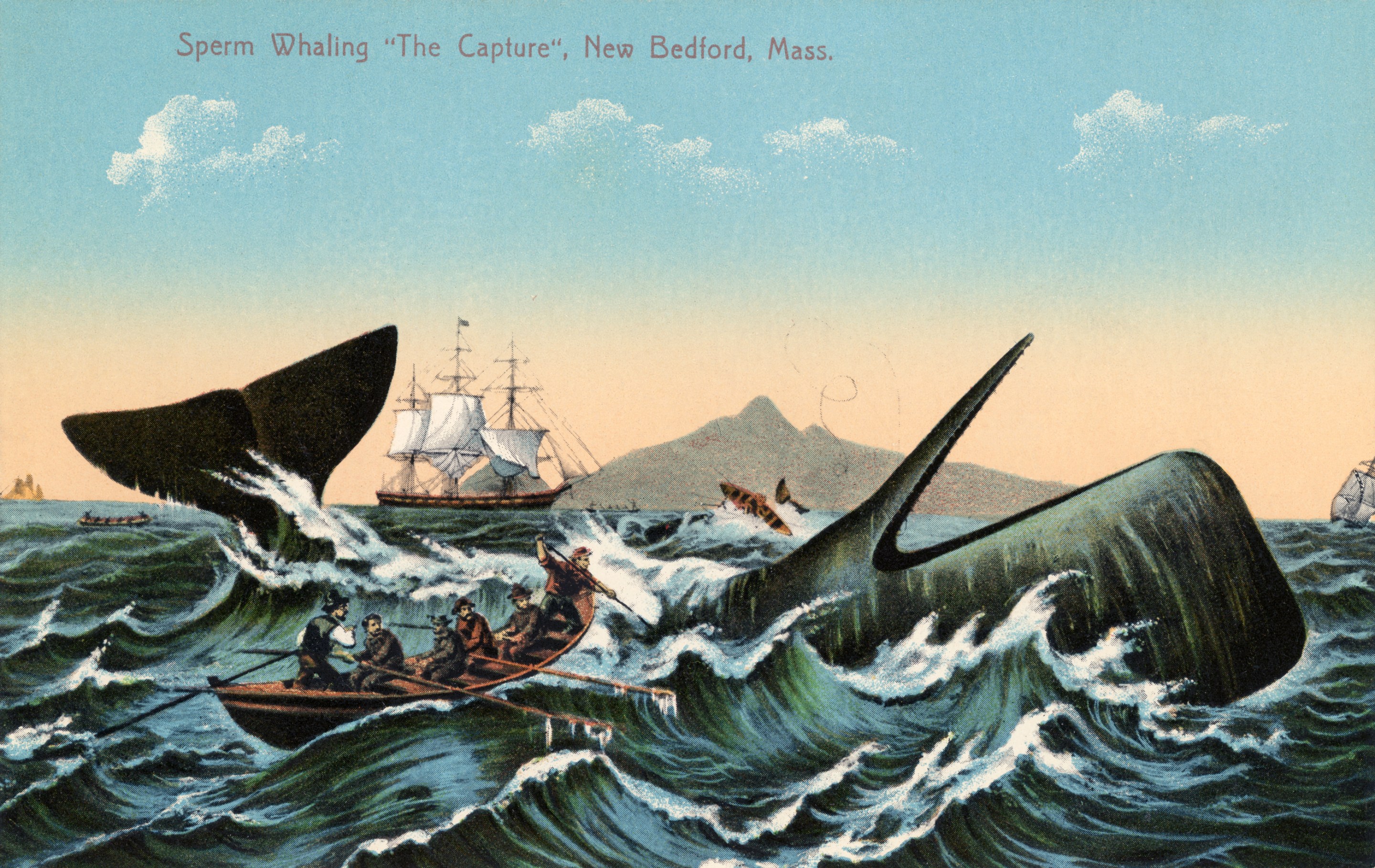

Yes, there are those many chapters of cetology, arriving seemingly at random and serving seemingly as filler, and therefore pretentious. But what Melville achieves, what many of the best books achieve, is a consuming rhythm, an internal logic that makes it so almost any digression feels motivated, interesting, even important. Here is a novel that follows men trapped within the groove of a destructive and dying industry, one whose violence and cruelty is held up as one of the few remaining paths to glory. “Perseus, St. George, Hercules, Jonah, and Vishnoo!” Ishmael exclaims. “There’s a member-roll for you! What club but the whaleman’s can head off like that?”

Indeed, Moby-Dick’s kaleidoscopic structure and kitchen-sink vernacular makes it a novel of surprising breadth and energy. It’s a polemic and a farce and a found document and a fantasy and a cautionary tale. At a certain point, it felt as if Melville had hit me over the head so squarely and relentlessly that I was forced—and glad—to give up any notion of figuring out what the book was about.

I read the first 400 pages of Moby-Dick with these feelings in mind. I vibed with what I had gotten through, constantly surprised by the novel’s vastness, its humor, its accessibility amidst long, sweeping sections of Shakespeare-inflected soliloquy. It can be embarrassing to admit that a book, whether because of its length or age or reputation or some combination, intimidates you. No one wants to feel stupid engaging with something that a lot of people “got” a long time ago, especially a classic that appeared on a high school or college syllabus you didn’t have. During this last year of so many ridiculous, bad-faith screeds—against reading things that are old or long or confusing or so permanently ingrained in literary culture that it seems pointless to revisit them—the prevailing sentiment, to me at least, was a kind of militant insecurity over one’s own taste and intelligence, and how that mapped onto the supposedly correct way to engage with a work of art.

That very dilemma—the expansive, tangled web of associations and parallel histories that inform and shape a novel as hallowed as Moby-Dick—makes up the structure of Dayswork, a novel by Chris Bachelder and Jennifer Habel published this year that might be the main reason I finished Moby-Dick. Because I started out the year with Moby-Dick in hand and a vague interest that quickly turned into genuine attention—this is how I ended up reading Dune three years ago and most of the Slough House series this year and Janet Malcolm last year and Brian Evenson every year and Tolkien and a number of other books I’d heard of but didn’t think were for me. I read all these first with almost amused skepticism, then with helpless feverishness—and then found I couldn’t keep going.

There wasn’t any single thing about the novel that kept me from finishing it. I told friends who asked that Moby-Dick had become my before-bedtime book, but eventually I kept falling asleep after a few pages. Days and then weeks went by and I’d start to feel guilty about how much time had passed since I last stepped onto the Pequod. I’d feel even worse whenever I did pick the novel up again because every page I read would remind me of the beautifully insane thing I was missing out on.

Dayswork takes place during lockdown and features a married couple, one of whom, the wife, becomes obsessed with the life of Herman Melville. “My husband says that I seem to have contracted Melville,” the narrator writes, “and it’s true that some mornings we find one of my crumpled sticky notes in the sheets like a used tissue.” Made up of stand-alone sentences separated by white space, the novel is both collage and diary, research project and intimate self-portrait. Melville comes across as an alternately brilliant, terse, earnest, blinkered, meandering observer of myriad forms of life that often don’t extend to his own family. “One of Melville’s friends called him a ‘Blue-Beard who has hidden away five agreeable ladies in an icy glen.’”

The narrator of Dayswork falls a bit in love with her subject and makes no exception for Melville’s cruelty. It’s less that the novel tries to cut Melville down to size and more the case that, like many other men of distinction, the finished product we revere was perfected by hands deemed less worthy of attention. In this case, Melville’s wife and daughters. “With the exception of Billy Budd, found in Melville’s desk after his death, all of his prose was copied by the women in his family…The nearly illegible manuscripts of male geniuses: One of Victor Hugo’s publishers likened his writing to a ‘battlefield on a piece of paper.’ One of Balzac’s manuscripts allegedly drove a typesetter to insanity. As for Robert Louis Stevenson, ‘No printer could ever make out what he had written.’”

Andrew Schenker, reviewing Dayswork for The Baffler, writes that the novel “is quite obviously informed by the upheavals of the #MeToo era, reconsidering the life of a prominent male author in the light of his treatment of the women around him.” As Schenker notes, there’s nothing didactic about that framework or its execution. Indeed, what makes the novel so moving and, for me, what made it so compelling to me as a springboard for my return to Moby-Dick, is how Bachelder and Habel distill history down into a kind of personal microcosm. Melville, the person, is glimpsed alongside Melville the sailor, the poet, the husband, the scholar. There is no triumphalism to Melville’s life; by the time he died, he had fallen into obscurity and Moby-Dick had been largely forgotten. More powerful, then, when the narrator of Dayswork re-emphasizes the sheer magnitude of Moby-Dick’s long afterlife. “‘Call me Jonah,’ begins Kurt Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle. ‘Call me Smitty,’ begins Philip Roth’s The Great American Novel. ‘Call me Monk,’ culminates the opening paragraph of Percival Everett’s Erasure.” It’s this context that makes Melville’s opus a surviving text as much as a towering achievement.

This fall, I got back to it. “It is noon; and Dough-Boy, the steward, thrusting his pale loaf-of-bread face from the cabin-scuttle, announces dinner to his lord and master…” I found I didn’t need a refresher on what had transpired months prior. Ahab continued his fruitless search amidst an international crew of silent brooders, ruffians, craftsmen, and broke(n) sailors. The ocean stretches forever in each direction, interrupted by the occasional brief conference with a passing ship. The grotesqueries of whaling itself make up a good chunk of the book. There are brief moments of grace, like when a warm breeze breaks through Ahab’s stern exterior —“More than once did he put forth the faint blossom of a look, which, in any other man, would have soon flowered out in a smile.”

Moby-Dick is long, sure, but its length teaches a reader how to engage with it. In some places, boredom is the point. In some places, there is monotony and circuitousness and restlessness, and then suddenly everything goes wrong. The life of a whaler, as Ishmael tells it, is dictated by divine precedent, luck, and the flaw of human interpretation. Life itself is a thing laid out simply and made more inscrutable with time. This concept spreads in many directions throughout the novel and sometimes, after so many short chapters on wildly divergent topics, Melville fires a stray, deadly arrow. For example, Chapter 42, titled “The Whiteness of the Whale,” stands out as one of the most arresting, bewildering things I’ve ever read. “Though in many natural objects, whiteness refining enhances beauty, as if imparting some special virtue of its own…yet for all these accumulated associations, with whatever is sweet, and honorable, and sublime, there yet lurks an elusive something, in the innermost idea of this hue, which strikes more of panic to the soul than that redness which affrights in blood.”

Through a contemporary lens, the chapter reads almost like a polemic against racial whiteness. Indeed, along the voyage, Ishmael vacillates between aversion and sensual admiration of his “savage” shipmates, their cultures, American culture, the realities of war and social division, even the category of man versus animal. Moby-Dick’s publication ten years before the American Civil War invites all kinds of analyses of its narrator’s anxieties, and of the maniacal enterprise of Ahab’s quest. Ahab’s wound is not only his missing leg, but his undying obsession with avenging something he can never get back, an obsession he’s aware of but powerless to change.“Forty years of continual whaling!” he cries to his level-headed chief mate Starbuck. “Forty years of privation, and peril, and storm-time! forty years on the pitiless sea! for forty years has Ahab forsaken the peaceful land, for forty years to make war on the horrors of the deep!”

Having spent so much of this year thinking about Moby-Dick, knowing how it ends only made it more tragic. It’s rare to be so caught up in a novel of any size. In an odd modern wrinkle, it’s also rare to read something that feels totally unsuitable for any kind of filmic adaptation. Idly reading the novel during lulls at work, whenever I’d forget what the tryworks of a ship looked like or how tall the main sail was, I’d Google “pequod ship illustration” and be disappointed to find that any real-world representations of Ahab’s vessel tended to be collectible wooden miniatures.

In that scene from The Pagemaster, Ahab, rendered as a white-haired, hook-nosed sailor, single-handedly alters the color and tone of his surroundings by the sheer force of his obsession. He spots the whale and everything—the sea, the sky, the boat—turns red. The Pequod isn’t even there. Instead, Ahab rides in a smaller whaling vessel propelled by oars. Moby-Dick rushes out of the ocean in a brief flash of gray before crashing down onto Ahab and his crew, a blur too massive and horrible to witness. This is maybe as close as one could come to approaching the emotional experience of the novel, unbound as it is from the constraints of objectivity, of rationality, of real life.

Starting and finishing Moby-Dick should have been fairly simple; I’m still not sure why it accrued incalculable resonance for me. Maybe because I had to keep returning to it and, in between, the books I read only made Melville’s novel seem even more detailed and refined than before. I wonder, in the future, when I revisit the novel, if I’ll still feel the same magnetic pull. I hope so. As described in Dayswork, “what D.H. Lawrence called ‘one of the strangest and most wonderful books in the world’ and what E.L. Doctorow called ‘the book that swallows European civilization whole’ and what William Faulkner called ‘the book which I put down with the unqualified thought ‘I wish I had written that’ and what Marilynne Robinson called ‘the most spectacular exploration of the metaphorical acts of consciousness’ and what Robert Coover called ‘the beast we’re all chasing,’” is indeed all of those things.

It’s also the product of mundane determination. “After eating his own breakfast, Melville went to his study, made a fire, then fell to with a will—He had until 2:30.” I’ve never been enamored with the craft of writing and so I find the genius narrative a little dull. The writers of Dayswork do, too. Instead, what lingers are the passages that feel ripped from the soul, the result of skill and acumen, of course, but also individual personality and the efforts of a mind that existed at a particular time and place. If one is lucky, you get to write a few of these passages. If one is lucky, you get to read a few. So I’ll end here with one of my favorites:

“Were this world an endless plain, and by sailing eastward we could for ever reach new distances, and discover sights more sweet and strange than any Cyclades or Islands of King Solomon, then there were promise in the voyage. But in pursuit of those far mysteries we dream of, or in tormented chase of that demon phantom that, some time or other, swims before all human hearts; while chasing such over this round globe, they either lead us on in barren mazes or midway leave us whelmed.”