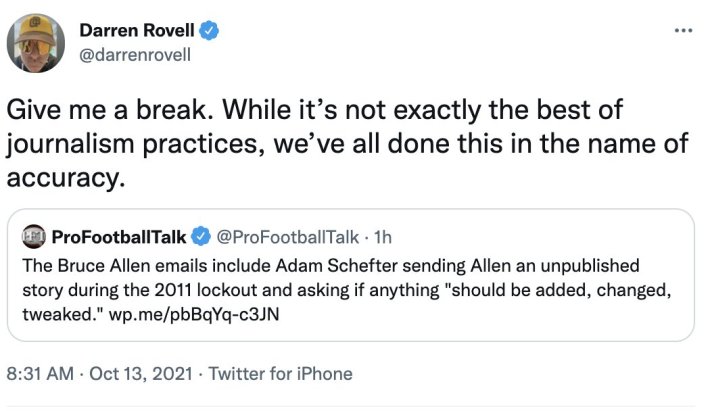

I do not know how many times Adam Schefter is going to climb to the rooftops and shout, I am a little worm! What I do is not journalism! before ESPN decides to care. Today is apparently not that day, though I guess we should thank Schefter for shouting it so loudly.

ESPN's scoophound shows up in the trove of emails to and from former Washington Football Team president Bruce Allen, which has already led to the forced resignation of Jon Gruden and presumably has a lot of NFL-connected folks gnawing their fingernails—the ones capable of feeling shame, anyway, and there's no reason to believe that includes Schefter.

The Los Angeles Times examined a cache of Allen's emails found in a federal court filing (and which is the source of some, but interestingly not all, of the Gruden emails so far reported on) and wouldn't you know what they found? Schefter committing one of the cardinal sins of reporting by sending a draft of a story to a source:

Several emails between Allen and journalists are part of the filing too. In one of them from July 2011, ESPN NFL Insider Adam Schefter sent Allen the draft of an unpublished story that was published later the same day.

“Please let me know if you see anything that should be added, changed, tweaked,” Schefter wrote. “Thanks, Mr. Editor, for that and the trust. Plan to file this to espn about 6 am ….”

LAT

"Mr. Editor"! Incredible. What a weasel.

It is probably worth explaining here not only that it is bad to send a story to a source for pre-publication review, but why it is bad. While I assure you this is not normal practice, and is indeed right up there as one of the basic tenets of journalism along with "spell people's names correctly" and "don't make shit up," and that all reporters know not to do it (both innately and from having it drilled into their heads by competent and ethical instructors, colleagues, and bosses), there is no reason a normal person would ever spend a minute thinking about it. But it's not some arcane, ivory-tower, j-school ethical holdover; it's common sense. Every source for every story is by definition an interested party, and their interest is in the story being reported in a certain way. That's not necessarily intentional or nefarious, but it's without exception—why else would they talk to a reporter? They want something out there, and they want it to be their version. That's a conflict of interest that's unavoidably inherent in the very idea of sourcing. This doesn't mean that sources shouldn't be trusted, but it does mean that they should not be the final arbiter of the story's content—especially when, as was the case here, the story was one about a conflict between two sides, and only one side was handed the rubber stamp.

The story in question was not the typical Schefter pap. It would be one thing if Schefter was asking someone to sign off on the sort of disposable, 300-word filler item he usually traffics in. Tom Brady, please let me know if you see anything that should be added, changed, tweaked in this story reporting that you still have "the will to win." That wouldn't be fine, exactly, but also who cares. But this story was actual news. It was a story about CBA negotiations between the players and owners during the 2011 lockout. It was a labor battle, with both sides keen to get their spin on events in front of the public. It was a story with real implications for the livelihoods of the people involved. And Adam Schefter chose to let someone from the management side of the bargaining table have final say on how it was presented.

This isn't about management = bad, either. It wouldn't have been OK if Schefter had sent his draft to an NFLPA source instead or in addition. Don't let anyone see the story! Talk to them for the story, then write the story by triangulating the facts as best you can given the various motivations of your sources. That's how reporting works, especially on a topic like labor negotiations where there's not always going to be one objectively true version of events. If you want a story to be both comprehensive and accurate, the very last thing to do is let one side have veto power over the other's words.

But how do reporters make sure they haven't made mistakes in their story, you might and should ask. They (or fact checkers, at the few outlets that still employ them [and for what it's worth, ESPN in 2011 was one of those outlets]) do this by running by their sources individual statements of fact, not entire stories. "Is it true that [fact X]?" would be a perfectly fine thing for Schefter to have asked Allen. "I have you here as saying [quote X about fact X], is that right?" would be not strictly necessary, but it would be acceptable. Because those checks are about accuracy. What Schefter did was hand over control of presentation, something that under no circumstances should belong to a source. When it does happen, it's a scandal. And it is a fireable offense in a good newsroom.

This all feels very obvious, doesn't it? You would think so, anyway.

ESPN released the following statement in response to the correspondence: “Without sharing all the specifics of the reporter’s process for a story from 10 years ago during the NFL lockout, we believe that nothing is more important to Adam and ESPN than providing fans the most accurate, fair and complete story.”

LAT

This non-response is more galling than Schefter's original transgression. Because we already know who Schefter is; he's been very clear about that. It should be on his employer to act as if it cares that core best practices aren't being followed. ESPN, which has pretensions to being a real newsroom, gives the lie away here—and does a disservice to the actual reporters it employs by not holding everyone to the same standards to which those actual reporters hold themselves. In fact, I'll go further: ESPN does a disservice to the entire industry of reporting, by the decades it's spent actively blurring the line between "journalist" and "personality" and insisting that basic ethical standards don't apply to all.

To give a source or subject of a story the power of approval of said story is not a thing that is done, for many and clear and good reasons. Not in the job in which Adam Schefter and his bosses pretend he works. It's common, however, in the jobs of stenographer or publicist. Maybe that's a more useful lens through which to view Schefter and ESPN.

Update: Schefter responds.

Statement from Adam Schefter pic.twitter.com/rBjBl9Km6b

— ESPN PR (@ESPNPR) October 13, 2021