Given that established, franchised intellectual property seems to be the last remaining thing that movie studios value, it's striking how careless they are with it. Some of this surely owes to the fact that "caring" is not an action that comes naturally to any executive cohort, and some of it reflects the naturally diminishing returns that come with telling the same stories, in the same ways, over and over. More worrying is the broader sense, which is sadly not limited to film and television, that years of stridently cretinous hyper-exploitation have eroded the culture's capacity to make anything besides money. There are a number of obvious reasons to question the belief that an industry can go on turning a profit without making anything that people actually want, but the most convincing of those might be the people who believe it.

Sometimes their dopey-smug button-mashing produces a proper boondoggle, but most of the time it just produces increasingly degraded and insulting reiterations of a familiar product; in that sense, it's easy to see why these executives are so impressed by AI. The actual intoxicant is stepped on until its only effect is inducing a mild headache and a faint sense of nostalgia. Franchises that started with real skanky magic, like Alien, end up as operatic and pompous as an old rock star; franchises that began lean and nasty, like Halloween, are tortured for decades until they become About Trauma, or Myth.

I want to believe that there is a reason why The Exorcist has thus far managed to resist this fate; David Gordon Green, whose planned three-film sequel arc begins this weekend with The Exorcist: Believer, was brought in to end this. Green is a strange case, a masterful technician and total goofball who still does vintage work directing The Righteous Gemstones but has otherwise become a specialist in this kind of reverent, formalist genre-IP resuscitation for big studios. As Keith Phipps noted at Slate, Green is also the latest in a line of distinctive filmmakers to take a crack at The Exorcist after William Friedkin—in order, these are John Boorman (Exorcist II: The Heretic), William Peter Blatty (Exorcist III: Legion), Paul Schrader (Dominion: Prequel To The Exorcist), and Renny Harlin (Exorcist: The Beginning). In a testament to what a hash previous attempts at leveraging this particular bit of legacy IP have been, Schrader and Harlin somehow wound up making the same movie—the studio, aghast at Schrader's version, had Harlin remake it almost entirely. It is a further testament to what a hash etc. etc. that the tantalizing concept "Director of Die Hard 2 remixes a Paul Schrader movie" produced some of the dullest work of either director's career.

I love The Exorcist, and am also pretty unbearable about stuff like this, and so part of me wants to believe that there is something in the original that is simply too uncompromising for the pressures of this industrial extrusion process. But while it's true that there is something hard and despairing at the center of the first film that makes it great, its tropes and beats have been riffed on and ripped off often and easily enough to prove that there's no such thing as a kitsch-proof cultural product. It might be more correct to say that no other potentially franchise-able blockbuster has been quite as serious as The Exorcist. It can be commodified, but it resists being cheapened.

While The Exorcist has inspired any number of cheesy knockoffs, its sequels are not really like that. I'm going to leave out the Schrader/Harlin mess of Dominion/Exorcist: The Beginning, from 2004; it's an illegible text, lousy with Shitty Early '00s CGI Hyenas and replacement-level "where is your god now?" dialogue. The Schrader Version, irresistible as it is in theory, is in fact very easy to resist.

It's easy to see why some people love 1977's The Heretic, in which a clammy and pained-looking Richard Burton investigates the exorcism from the first film and tries to determine whether the demon Pazuzu is still lurking somewhere within Regan MacNeil. It's also easy to see why many more people hated it. Blatty, who adapted his novel into the screenplay for the original, loathed it; Gene Siskel wrote at the time that it was "the worst major motion picture I've seen in almost eight years on the job."

What the film offers, in lieu of any actual scares or coherence, are some truly berserk 1970s aesthetics, a bizarre cast, some striking photography, and a few memorably jarring dream sequences. For all the Catholic kitsch and literal exorcism stuff it includes, The Heretic has more in common with more commanding movies from the era like Peter Weir's The Last Wave, where the membrane between dream-time and reality becomes first unsettlingly permeable and then just disappears. It honors the grim '70s doominess of the original only glancingly and with little conviction, but the scope of its metaphysical ambition is a tribute in its own right—maybe the studio's idea was to cash in on some lucrative IP, but Boorman was more interested in universal consciousness. It's a mess; the version released on home video is 17 minutes shorter than the theatrical.

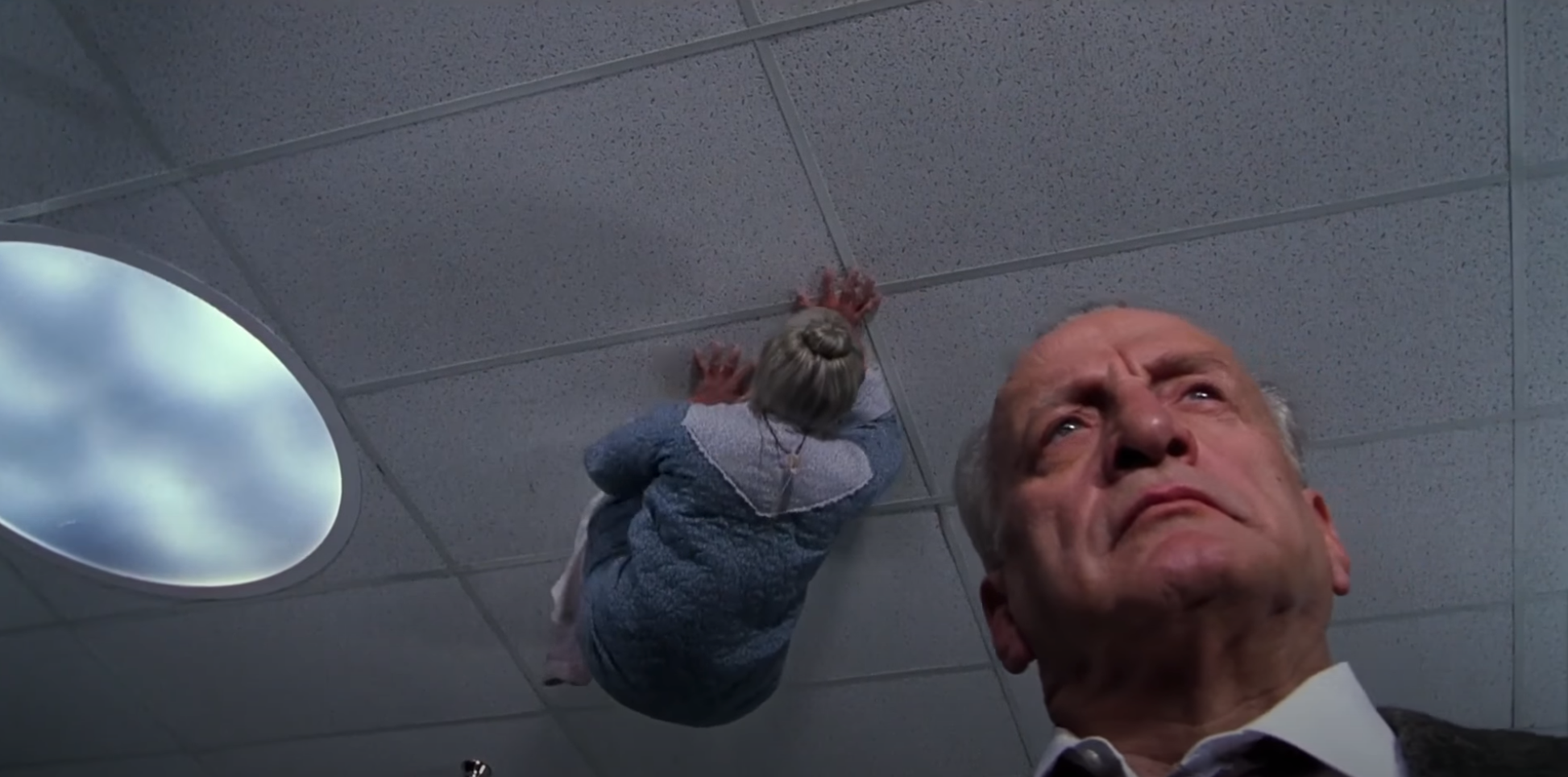

That rough treatment is nothing compared to the travails of Exorcist III: Legion, which came out in 1990. The film had such a troubled production that it currently exists on Blu-Ray as two similar but identifiably distinct films. Blatty wrote and directed both, and they have a great deal in common; I love them both, and if I am defensive about David Gordon Green making three reverent, formally accomplished, ultimately forgettable new sequels to The Exorcist it is in part because of how weird and wonderful I think Blatty's spectacularly heretical and formally psychotic attempt remains.

Blatty only directed one other film, the ultra-woolly 1980 existential comedy The Ninth Configuration, which is the only movie I can think of that remotely resembles Legion in tone or content. Both are cluttered, visually and intellectually, with Blatty's crew of character actors exchanging wild burns and windy comic disquisitions on faith in chaotic visual frames; in both cases, it is hard to imagine that a film so clearly and sincerely preoccupied with serious things could also include so much banter. A number of actors who showed they could do The Blatty Thing in The Ninth Configuration—Ed Flanders, Scott Wilson, Jason Miller, George DiCenzo—return in Legion.

It helps, here, that the banter is so strange and often extremely funny; the relentless comic back-and-forth makes for an especially bracing contrast when interrupted by some ominously unhurried horror set-pieces and Blatty's signature busy deep visual compositions. The cut Blatty gave the studio didn't even have an exorcism in it, which did not please them any more than you'd expect. "The first one was never what he wanted, the second one was unspeakable, and the third one was where he was going to make his case," the film's co-editor Todd Ramsay says of Blatty in a special feature on Legion's Blu-Ray release. “And there’s nothing wrong with that except where it collides with commercial interests and millions of dollars, which is what a movie is.”

The studio demanded that Blatty do a bunch of stuff that he didn't want to do, and he did it. George C. Scott, playing the detective character that Lee J. Cobb played in the original, now on the case of what might or might not be a body-hopping serial-murdering demon, came back to snarl through that exorcism scene. The film historian Mark Kermode describes Scott, disgusted, as saying that the studio "wouldn't have been happy unless Madonna showed up and sang a song at the end." Brad Dourif, who gives one of the best and scariest genre performances I've seen, was cut out of the original entirely, then replaced with Jason Miller, who played Father Damian Karras in The Exorcist, and then called back to reshoot his entire part in three days when the alcoholic Miller struggled to remember his lines; the final studio version includes both actors. For a film that flew in Shakespearean actor Nicol Williamson to shoot an emergency exorcism scene that was written on the fly—an effects hire talks about Williamson offering him "Heineken and strawberries"—the result is rather shockingly good.

Many years later, Blatty was able to piece together something more like his original version; it's called Legion, and is also something of a mess. The original 35mm film was lost; editors used what a pre-credit card calls "a pallet of film assets from the original shoot," including dailies shot on VHS, to recreate something more like the original. This includes the brilliant and more fully inhabited performance that Dourif gave the first time, and doesn't include Miller at all. It is patchy, and not notably more coherent—a lot of what Blatty restored, delightfully, are bits of oddball dialogue—but it is singular, and pared back to Blatty's main concern, which is what kind of God would let things be the way they are. Where The Exorcist's anxieties resound with the tumult and shame of the 1970s, Legion's have a distinctly '80s feel—a sense that things have not merely slipped out of joint and into a vast cruelty, but been left to become stuck there. Also there are cameos from a lot of '80s Guys: C. Everett Koop, Larry King, Patrick Ewing, Fabio. Everyone in the hospital smokes.

A production designer sniffs in the special features that Blatty thought his original version was "a masterpiece." This is said with disapproval; the production designer thought it was "totally leaden, and without redemption." The first bit is a matter of taste; the second, though, is not just a choice, but something like The Exorcist's defining aspect. It fits that the studio-mandated reshoots to every previous sequel tried, to some degree, to make it clearer that the good guys had won.

The Exorcist, for its part, ends on what is only barely a hopeful note; there is not the sense that evil has been defeated, by ritual or various brave people's sacrifices or anything else, so much as that it has been temporarily displaced. Lore aficionados will be happy to hear that Green apparently brings back the demon Pazuzu in his sequel. But, in Legion as in The Exorcist, even demons are just soldiers in a sprawling campaign of terror in which every human is overmatched and at great risk of becoming collateral damage; some great cruelty is at work, taunting the righteous and punishing the vulnerable, and that is just how it is.

Legion, the movie the writer wanted to make and sort of did, has people talking about this a lot; The Exorcist, made by a master, makes that threat feel more urgent. The other sequels grope toward that vastness without much in mind, but every Exorcist movie kind of has to be about that to be an Exorcist movie. This is not a universe waiting to be expanded so much as it is just the same story, repeating itself and defying resolution—less like one of those more malleable properties that wind up being About Trauma, and much more like trauma itself.