COVID-19 vaccinations are coming. Our ragged, under-resourced system is chugging its way up to speed; 1.7 million people—a new record!—were vaccinated on Feb. 4. On Feb. 5, Lloyd Austin, the new Secretary of Defense, approved FEMA's request to deploy active-duty military personnel to assist with state's efforts to distribute COVID-19 vaccines. Whoever you are, wherever you are, whatever your particular relationship to the virus and its vaccine, the progress of the U.S.'s accelerating vaccination program is going to shape your future, fairly soon.

But that is not the same thing as saying that everyone is going to be vaccinated. People with suppressed or compromised immune systems may not be able to be safely vaccinated; people with certain severe allergic reactions to any component of the available vaccines, or to injectable medication generally, may not be able to be vaccinated; children have not yet been approved for any of the stateside COVID-19 vaccines.* And then there are those who do not fit into any of those groups who will refuse to be vaccinated. And buddy, there are a shocking number of those types out there. Roughly 38 percent of Americans say they probably or definitely will not get vaccinated against the SARS-CoV-2 virus, according to a Pew Research poll from December. And that awful, frightening number represents an increase in confidence in vaccines among the general public.

America, you may have noticed, has a screwy relationship with vaccines. You are familiar with the general anti-vax movement, fueled and sustained by falsehoods and misinformation spread among brain-wormed crazies in deeply deranged online cesspools. As ugly as that whole scene is, it would almost be comforting to think that it constitutes the entirety of the vaccine-hesitant segment of the population, except that would mean damn near 40 percent of the American public has had their brains ruined by the Facebook ravings of divorced uncles and Jenny McCarthy. Still, if vaccine skepticism were just one thing, then you might reasonably address it with one solution.

It's not one thing. Our whole healthcare system is a mess, and for people toward whom that big mess has historically and recently been overtly hostile, skepticism of its latest breakthrough is both a distinct challenge and a whole hell of a lot more justified. Black, Latinx, and Native American people are roughly four times as likely as white people to be hospitalized due to coronavirus infections, and are roughly three times as likely to die from COVID-19, according to CDC data. A whopping 71 percent of black Americans know someone who has been hospitalized or died of COVID-19. As with all our other cruelties and afflictions, the ongoing pandemic disproportionately affects these marginalized, underserved, vulnerable groups. Which is why it is especially vexing to learn that black Americans are in general more hesitant to be vaccinated than the general population.

So it's a complex problem. To help Defector get a handle on this stuff, I spoke with Dr. Jamie Slaughter-Acey, an epidemiologist and assistant professor at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health. Dr. Slaughter-Acey focuses her research on inequalities in our healthcare system and how they are manifested by the forces of social class, racism, and patriarchy. She has thought long and hard about the challenges of distributing an absolutely vital vaccine to an American public with a deeply beshitted relationship to the healthcare system more broadly, and to vaccination programs more specifically, and also has a remarkable ability to explain how medicine works to moron bloggers. This conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

So, what is a vaccine? Like, what is it, and how does it work?

OK, that's a really good question. So, a vaccine is meant to trigger our immune response to a virus, without us developing a disease from the virus. That's what a vaccine is, in the most basic sense. It's solving the problem of how we trigger our immune response so that our immune response protects us from the virus, as well as the disease that is associated with the virus.

So it's like, how do we get our immune system to fight this virus without first becoming sick? By the virus?

Exactly. And that's really important when the symptoms of the disease that's associated with the virus can be really severe and lead to reduced quality of life, and morbidity. It's important when there is a relatively high mortality rate associated with acquiring the disease. And so very early on with COVID—or with the SARS-CoV-2 virus that leads to COVID symptoms—we noticed that there was this high mortality rate when people did develop symptoms, and so a vaccine then becomes very important, because we don't want people to acquire immunity just by being exposed to the virus and risking their life.

That would seem like a pretty inefficient way of developing herd immunity, yeah?

Exactly. And if you go back to the late 1700s to early 1800s, and look at a virus like smallpox, one of the first ways we inoculated people to protect them from dying as a result of smallpox was by exposing people who had never had smallpox to material from the smallpox sores or cowpox sores so they would build up an immune response. And that's really dangerous! The development of vaccines was really a game-changer in the way that we can practice public health and protect the population from infectious diseases.

Now I have what is probably a very dumb question.

There’s no dumb questions! I tell this to my students all the time.

You might be surprised! So my extremely not-dumb question is: Are there viruses out there—common viruses that people can catch—that are so benign that we would not bother developing a vaccine? Because the human body will just kick its ass or whatever?

There are some viruses that are quite prevalent or common within the population that we don't have vaccines for because they are rarely harmful. An example of that would be cytomegalovirus. A person can be exposed to cytomegalovirus at birth; most people who acquire cytomegalovirus, they acquire it in their early adolescence to young adulthood; most who acquire cytomegalovirus have a healthy immune system that fights off any illness from it. And the virus remains dormant in our body until the day we die.

For women who become pregnant, there's an increased risk of a dormant infection of cytomegalovirus becoming reactive, which in rare cases leads to possible neurodevelopmental disorders with the developing fetus. But otherwise that's an example of a virus which for the general population we're not so worried about its effects.

And then with scarier viruses, the viruses that are treated with a vaccine, how do we know the vaccine is working? Like, what is meant by “efficacy?” Is it preventing the virus from making you sick? Preventing the virus from killing you? Preventing you from spreading the virus?

That's a really good question. And actually what you did there was packed in, like, several questions.

Sorry, I am getting myself all worked up, here.

I'll first start by just sort of disentangling the questions. So part of what was in there was, is the vaccine effective against transmission of the virus? That's A. B: Does the vaccine prevent one from developing symptoms? And then C was the prevention of death.

So the way that the trials were developed, in terms of testing the efficacy of the vaccines that different pharmaceutical companies were creating, the primary goal was trying to create a vaccine that would prevent severe complications related to the virus, the conglomerate of the worst symptoms caused by the virus that we call COVID-19, and where we see high fatality rates. Then the question is how well does this vaccine perform in terms of preventing someone who is infected with SARS-CoV-2 from developing mild to moderate symptoms related to COVID-19.

Now, the question of, does the vaccine prevent the transmission of SARS-CoV-2? The answer to that is we do not know.

Rats.

And that is because the trials were designed to answer that first question. Do the vaccines prevent you from developing COVID-19 complications? That was the first layer of data that all of the clinical trials were trying to assess, as well as the safety of the vaccine itself. And so it sort of remains to be seen whether or not data is going to come out of the trials that demonstrate whether or not the vaccines also reduce the transmission.

So we will learn that at some point, we just haven’t learned it yet?

Right. It wasn't the primary focus. If you think about this sort of as an iceberg, the tip of the iceberg is mortality. And then just underneath that is the morbidity and the reduced quality of life of COVID-19 sufferers. The base of that iceberg is made up of people who have tested positive or have acquired SARS-CoV-2, but they're not exhibiting symptoms, at least as we know of them. And so from a public health perspective, when you're thinking about creating a vaccine, when you have something that once the complications start to set in has such a high fatality ratio, then you want to focus in on creating a vaccine that's going to prevent those complications. And that's why that first set of data is to answer that question. I suspect that additional data about efficacy in relation to transmission will come out later.

I saw what I thought was a pretty bold take, in Wired, that argued that vaccination efforts should prioritize superspreaders over the vulnerable. But I guess in the absence of information about the efficacy of the vaccines at preventing transmission, that would be a bad idea.

Absolutely. Right now we think that the vaccine is most likely helpful in reducing transmission, but we don't have the science to back that up yet. So we can't do what I guess you could describe as sort of a reverse plan, vaccinating the superspreaders. The ethical piece here, or the moral piece, is that you would be vaccinating the people who put others most at risk first. Right? And eliminating their risk of developing COVID-19. But they would still be going about their regular business, and could be spreading virus to other people. So that puts you in a little bit of a moral and ethical dilemma. I think once we get that science out, and if it shows that these vaccines actually reduce the risk of someone transmitting the virus to another person, then I might take that approach of prioritizing the superspreaders.

I suppose another challenge of prioritizing superspreaders, even if we learn the vaccine prevents transmission, is some relatively high number of superspreaders, almost by definition, will be COVID-truthers, and so are probably more likely to reject the very idea of a vaccine.

Yeah, I mean, we're in a really complicated situation! And it is a situation that didn't have to be as complicated as it is, right? There's always going to be people who are going to be never-adopters, right? Who dismiss the science, who are going to believe this is, you know, “fake news.” There's gonna be people who are very self-oriented in thinking about the health of society and their contribution, their role within that.

But I think you also have this group of people in there who are potential superspreaders who, if we’d had a clear message around the pandemic and around mitigation strategies from day one, would in fact be in the opposite group, right? They wouldn’t be in the group of superspreaders! I think, you know, you probably have some readers that are just like, “I'm hearing so many different things, I'm tired, I don't know what to do, I just want my way of life.” It may not seem like we're asking people to do a lot, right? Like we say, just lay on your couch and watch Netflix. It doesn’t seem like the same type of sacrifice our grandparents made when they had to, you know, deal with rationing food and other items to support a war effort. This is an invisible war. And that makes it so much harder for people to get on board in terms of what their role is, in helping to form a resistance.

Even dead-simple, no-brainer stuff, like wearing a mask, I think there’s still a lot of confusion about what a mask is exactly for, and what it actually accomplishes.

Absolutely. I mean, one of the things we do in this country, and this is actually just human nature, is that we break people into groups. We “other” people, right? It makes certain circumstances seem more distant from us, or less likely to be relevant or affect us personally. And that's one of the ways that we as humans try to deal with fear, or things that can cause fear and anxiety. I think that's one of the things that we're dealing with in terms of people wearing masks or social distancing, that they don't recognize the severity of the danger until a close family member becomes infected and has severe complications, or they themselves have severe complications.

Part of it is just making the issue more proximal to people, but I think the other piece of it, if we just look at the mask issue, there was a lot of mixed messaging from day one, about the efficacy of masks. Does any type of mask work? Do masks protect me, or do masks protect others? Who should wear masks? You know what I mean? And because the messaging as well as our understanding of the virus was changing—we didn't have science around all of this at the beginning—some people were making bold statements about masks before we actually had the data, about whether masks work and these types of masks work in these types of settings.

But with the science that we know of today about the virus, we know that wearing a mask that consists of two layers not only gives you some protection, but it also protects others around you. Now, a mask that has a more effective filtration system increases how much that mask protects you and how much that mask protects others. And we know that the efficacy of masks is at its highest when we all wear masks, and goes down as individuals opt out of wearing a mask.

Confusion about vaccination is even worse, right? The other day Michele Roberts, the head of the NBA players union, made comments about her own hesitancy about the vaccine. It’s sort of alarming to hear that from such a prominent person, but it also drove home, for me, that there’s a lot of vaccination hesitancy out there that gets sort of drowned out by the anti-vax movement. Like, there’s a very vocal group of online-brained conspiracy theorists, but I also saw a Kaiser Family Foundation poll from December showing that almost 40 percent of black adults in America expressed some level of hesitancy about getting the COVID vaccine. That’s gonna be a big challenge, right? Overcoming the skepticism of people who weren’t radicalized by like Jessica Biel, and who come by their mistrust of our healthcare system more honestly.

That's a huge challenge. And you're right, they're two different groups, the thinking at the core for each of those groups is very, very different. With anti-vaxxers, I really don't know if you could change their decisions on this. Because I think their decisions are based more off of belief than fact. I distinguish anti-vaxxers from people who have vaccine hesitancy. A person who has vaccine hesitancy might still believe in the value of vaccines, but maybe they have questions about whether a given vaccine is safe for them, based on either knowledge or miscommunication, misinformation, or past experiences with, let's say, the healthcare system or the government. Whereas an anti-vaxxer does not believe in the very idea of vaccines.

So these are two completely different things and groups. When talking about the group with vaccine hesitancy, I think you can actually sort of break them out into two subgroups. There are those who are hesitant—or they're saying they're not going to take the vaccine—but it's based on misinformation. Because we know that there's a lot of misinformation out there, in terms of how vaccines work. Is it the live virus being injected in you, and so forth. And if you can clear up that misinformation, then for these individuals their hesitancy around the vaccine begins to disappear.

Then there's the group whose hesitancy is stemming from mistrust that develops because of poor community provider-patient communication, their past experiences with the healthcare system, as well as historical experiences that these social groups like African Americans have had, with respect to vaccine development, or investigating the manifestation of certain diseases, like the Tuskegee syphilis study. And those stories very much are carried forward, whether black Americans consciously know it or not.

Well, and I realize this is too big a question, but how do we overcome or reset that relationship so that folks are comfortable with the vaccine? It’s obviously narrow and insufficient to just look at it as a COVID vaccine problem, but obviously there’s some great urgency there because, like, that group still needs to be vaccinated.

Yeah, no, that's a really good question. Because you're right, this isn't something that has occurred overnight, and it's bigger than just the COVID vaccine. It is a consequence of intergenerational and structural racism, this mistrust between African Americans and other people of color who are marginalized by systemic racism, and the healthcare system. And that directly plays into the way that individuals interact with the healthcare system.

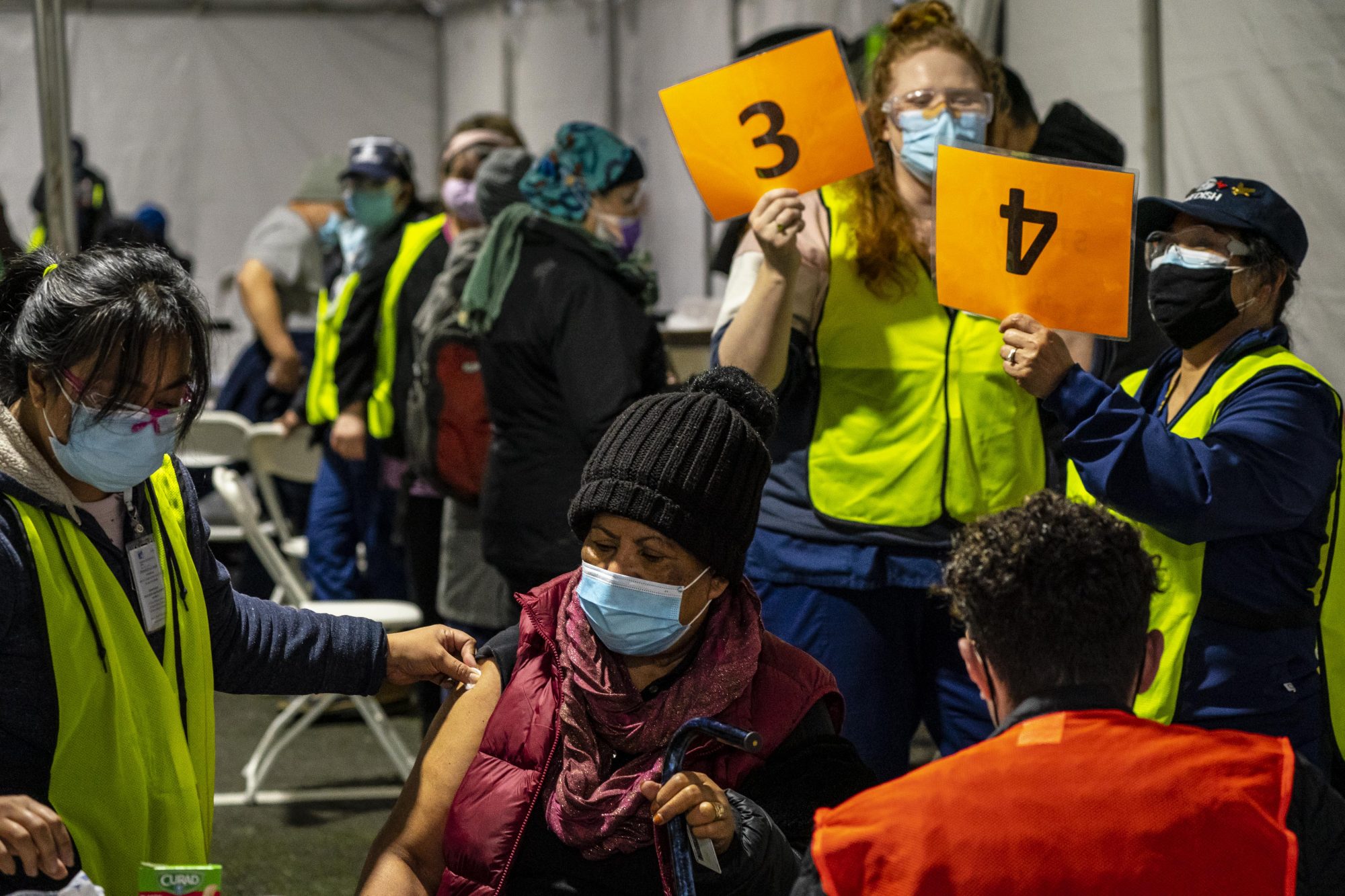

We can't go back, we don't have a time machine, so we can't go back in time and undo all of that. Knowing that we're stuck in the present, and COVID is exposing those consequences in a way that nothing else has, we have to sort of think about addressing this problem from multiple avenues. So, for example, one aspect of structural racism is neighborhoods that are majority black or of color tend to be less resourced. If we're thinking about using pharmacies as a way to disseminate the vaccine supply, that's gonna be an issue. And so it's recognizing where structural racism creates a barrier that will inhibit the administering of the vaccine. These under-resourced communities often are pharmacy deserts. Or even healthcare deserts, more broadly.

The use of mobile clinics would help, or partnering with churches, you know, the resources that are available in those communities to create clinic sites, existing structures that can house these clinic sites. Community clinic sites become more important.

Another solution is ensuring that we're communicating the right message, the truthful message and being very transparent about the vaccine. Because some of the hesitancy that's coming from this group grows out of structural and intergenerational racism. You have to be really transparent: this is the benefit, this is what you stand to gain from being vaccinated, and these are the risks. And clearly talking through the risks, so that they understand what these risks are. And then there’s developing an understanding of what they perceive to be the risks of taking the vaccine. Right? We can often mitigate that mistrust.

There's some really good research that has been done around flu vaccines and the lower rate of flu vaccination among African Americans. And one of the things that this research speaks to is that the perceived risks of getting vaccinated are not universal across populations. Some groups are going to perceive risks associated with vaccination that another group doesn't. And so it's really understanding the risk/benefit ratio that the individual sees, and having that conversation about those benefits and those risks.

So for my family, I'm a black epidemiologist, right? So I'm an epidemiologist, I understand the science. And I'm also an African American, who knows the stories of Tuskegee along with, for example, the forced sterilization program in this country. And I've had my own experiences with the healthcare system, I have not always felt like I've gotten the best treatment because of my race. Or when the staff found out I am an epidemiologist, the way that I'm treated is completely switched or changed. So I understand that, but at the same time, the risk of me not getting the vaccine, and what that could do to my family, my community, that risk to me is greater than any side effects of the vaccine.

And I've had this conversation with my extended family. I have an elderly cousin, 87 or 88 years old, she’s like an aunt to me, and she has diabetes, she lives by herself, she's lonely. And she's very committed to her church. And so we've had to have a conversation about going to church. You know, if she says, “Jamie, I miss my favorite little cousin. I can't wait to see you. etc.,” my literal response is, “You know, Cousin Shirley, I'm not coming to visit you until you get vaccinated, because I am not going to have your death on me. And given that, if you want to see your little cousin, you know what you have to do?”

Was that approach successful?

Her response to me was, “I have been told, and you don't have to worry.”

And she’s gotta be coming up on her turn, right? At her age, she’s gotta be in the group!

The group’s gonna grow, you know, as long as there’s the supply. And then getting it to her.

For me, as an African American, but also as an epidemiologist who understands the science, I have to think about my role in the family, right? Who falls into that vulnerable group? The extended family—I speak to them about why it’s important to have a vaccine.

And I also think it's important for me to use science communication as a platform to speak to black Americans about why they should get the vaccine. And really the bottom line is that COVID-19 has ravaged the black community. Any potential risk of this vaccine is so small compared to what continued lack of vaccination will do to the black community.

Well, and that raises questions about the prioritization hierarchy of the vaccination program. Right now it seems like it’s healthcare workers and this sort of narrowly defined range of vulnerable groups, like the elderly and people with diagnosed comorbidities. But by all measures black people have been disproportionately harmed by the coronavirus, including and especially with respect to severe complications and deaths. It would seem to make sense, then, to treat black people as a vulnerable group? For the purposes of establishing a vaccination order?

It makes absolute sense. I will say it will never happen, because that would require the portion of our population that is privileged to give up some of their privilege.

That would require people who live in well-resourced neighborhoods, who don't have any comorbidities, who have reasonably secure income, to kind of absorb a little bit more of the economic shock. They would have to kind of give up a little of their privilege, give up their place in line, for someone else who's less privileged to become vaccinated. And while it's not 100 percent synonymous, it very much goes in line with that idea of white privilege. In this country—and it's because of racism—there is this white privilege. And as long as this country honors the idea of white privilege within its policies and laws, designating vulnerable groups based off of complication and death statistics, the racial statistics, will not happen. Because then public health will run up against a legal wall.

U.S. policies practice what we call in my world “colorblind racism.” They’re colorblind policies. They don't acknowledge color. They are supposed to be representative for everybody, but they don't consider that everybody isn't necessarily starting off at the same place. And so these colorblind policies disproportionately burden those who are already disadvantaged, and privilege those who already are privileged.

The workaround with it is sort of looking at where do black Americans, Latinx, indigenous people, those groups that are most affected by COVID-19, where do they fall in terms of their engagement with the economy? If you look at the distribution of who is an essential worker?

Overwhelmingly made up of people of color, and low-income people. And so identifying essential workers as a group, that's an extremely vulnerable group. They should be at the front of the line for vaccination. But what you would have is someone with white privilege getting mad that someone with less privilege is being given the vaccine first and filing a lawsuit.

God, that’s hideous to think about.

It is! But we're conditioned! Our society is conditioned to think like that.

What was that really stupid affirmative action case, about college admissions? There was one with like the University of Texas that was just this total bad-faith argument being used to defend an existing hierarchy of privilege. Anyway, it would be exactly that.

You would get someone yelling about “reverse racism” or “reverse discrimination.” Which there's no such thing as reverse racism! I mean, you're not giving up privilege to become disadvantaged, right? You are just becoming like everyone else.

When you talked just now about the disproportionate burden taken on by already disadvantaged groups, that brings to mind your study I saw recently, about racialized microaggressions in hospital environments leading to delayed prenatal care for some pregnant black women. It was a really bleak reminder that in addition to the big-picture burden of less access to healthcare overall, there’s also this kind of death-by-a-thousand-cuts burden that comes from entering a hostile environment in order to get even the care that’s available.

So there was a national survey that was conducted by a partnership between the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, NPR, and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. They surveyed individuals, representative of the five major racial groups we use in a census—so whites, blacks, Asian Americans, Latinx, and Native Americans. And I'm just going to speak to the African American data, because that's what's fresh off the top of my head. The survey asked: How often do you avoid needed services because of fears of discrimination? Of individuals who participated in this survey, 20 to 30 percent of black Americans say they avoid asking for, going to, or engaging that needed service, in order to avoid discrimination. It was like 20 percent said they did that with respect to healthcare, in general. And 30 percent said they did that with respect to the police. And so the idea behind the study that you're talking about, the one that I did, looking at whether racial microaggressions are associated with women not getting prenatal care, is really built off of that idea, that people avoid needed services because of fear of being discriminated against, or based off of their past experiences of being discriminated against. They don't want to subject themselves to additional maltreatment.

A lot of people focus on discrimination within the healthcare system. And that's really, really important. But if we were to solve that, and administer quality care for everyone who used the health care system, we'd still be faced with health disparities, because there's a large group of people who don't interact with the healthcare system, because of their past experiences with racism.

And it's not just past experiences with discrimination within the healthcare system. We're talking about experiences of discrimination or racism within any system. Racism within any institution in our society has implications for the way people engage with the healthcare system. So if you really want more of a long-term strategic approach, if you want to address mistrust of vaccinations, or vaccine hesitancy, or mistrust of the healthcare system; you would address the structural racism that's in the criminal justice system, in the ways that police interact with black communities or communities of color; you would address the structural racism in the education system, how teachers and how administrators in school districts engage with communities of color; you would address structural racism in housing; you would go sector by sector through this country and overhaul it to employ anti-racist policies.

You would have to shift the culture. The culture within each of these institutions must uphold anti-racist ideas, which really is everyone is treated, you know, justly, with equality, as a whole person. And in addressing that you address the mistrust with the healthcare system. Anything else is like a band aid.

That would be a real shock to the system, because the system is also positioned to take advantage of the fact that large percentages of people from marginalized groups will just sort of opt out of engaging with it, as a result of racism. This came up when NEC Director Brian Deese talked to the press recently about economic stimulus, how in previous rounds of stimulus under the Trump administration resources were not making it to black- and brown-owned businesses, because those businesses tend to keep more of a distance from banks and the government. That doesn’t mean they don’t need and deserve the stimulus! Just that the way our system operates, it tends to help only those people who are best positioned to engage with it, and to leave out anyone else. And in the case of stimulus, that sure kept the financial commitment down!

There’s a philosophical difference there, between a theory of government that has something for you so long as you can get to it, versus a theory of government that sees where there’s need and then reaches out with help. We have the former, and that naturally advantages the privileged.

Absolutely. I mean, it's a difference between a government being active versus reactive. In supporting the health of its citizens, the way that we've handled COVID-19 has been reacting, not just from day one, but even today. Right now, it’s all reaction to what's going on. And some of that, the way that we have addressed the pandemic, stems from the fact that we are a capitalist country. We have created a healthcare system that has a goal of creating capital. And if creating capital is what's most valued by a system then anything that relates to the quality of life is naturally going to fall below that.

One of the things that I say all the time when people talk about the healthcare system not being designed to address those who don't proactively interact with it is that that's not a bug in our healthcare system. It was designed that way. It wasn't designed to include communities of color. And we can look at history. It's only since the passage of Medicare that we've had desegregated hospitals. The reason why they were desegregated is that in order to receive Medicare funding, you had to desegregate. So what's that? That incentive? What's motivating that change? Money!

In order to stop being reactive to this pandemic, and shift to being proactive in dealing with it, we're going to have to change that hierarchy. Money can no longer be number one in the hierarchy. People—human life—that has to be number one.

So I guess it goes without saying that you would support Medicare For All?

I would definitely support Medicare For All! Or another type of universal healthcare program. Yeah, I’ll just leave it at that.

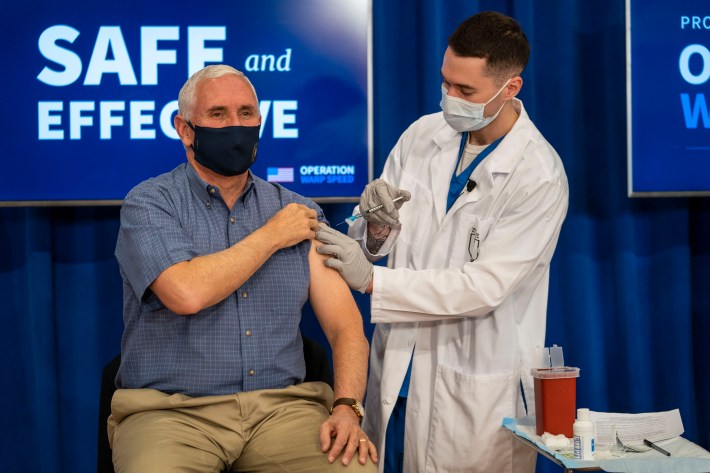

Who in your estimation should be handling the vaccine rollout? It’s going pretty slow, right? We have someone on staff here who is convinced that the National Guard should be administering the vaccine.

I mean, I think you have to be very careful about who you're going to have as the disseminators of the vaccine. Maybe for the general white public, having the National Guard disseminate the vaccine, that is probably fine. But you have to think very carefully about that when you're talking about communities of color, especially in geographic areas that have been over-policed, or, for example, here in Minneapolis, St. Paul. The National Guard was recently called out this past summer over the death of George Floyd. Think about, how does the National Guard interact with communities of color here? Right? And if that is the only, or the most recent interaction that they've had, then they would not be the ones that you'd want to disseminate the vaccine. You would want to identify another partner.

You would favor more of a multi-pronged approach.

But not a thoughtless multi-pronged approach. I mean, I think the federal government definitely should have the leadership role in ensuring that we have the vaccine supply, that states have the funds in administering the vaccines or setting up the infrastructure. That would help with the administration of the vaccine, ensuring that we have enough PPE, and that PPE is distributed in an equitable way. The federal government has different resources at hand that can be used to help, in terms of manpower. You mentioned one of them, the National Guard, so I will mention another: the Public Health Service Corps.

I’m not sure I knew there was such a thing as a Public Health Service Corps before this very moment.

I didn't know until I got into public health! But there is a Public Health Service Corps! I can't remember exactly how long their terms are, but you enlist in the Public Health Service Corps, and you do a stint of service. I think it's like four or five years at a time, it operates just like another arm of the military, but it's not housed under the military, it’s housed under the Department of Health and Human Services. Many of the Public Health Corps have been long-time workers for the Centers for Disease Control, or they've been working in local health departments. But they're very much committed to the health of the nation.

And they were called upon when we had that SARS outbreak back in the early 2000s. They were called upon to help do screenings or do tracing for SARS. For example, I had a colleague who was called up to do screenings at the airport. So they can play a very important role. And for this they may have better trust, a better trust relationship. So that could be a piece of it.

But I do think the other piece of it in terms of the approach for distributing vaccines, especially when you're talking about marginalized groups, communities of color and also low income people, or people experiencing homelessness, is that you have to center at the margins, right? You have to put them first and think about the conditions of their daily life. You want to get their input and you want to include their leaders. So that you create a distribution process that is both realistic and that they can and will engage with.

As someone who is probably pretty far down the priority list for vaccination, should I hold out for the one-shot Johnson & Johnson vaccine? Or should I go first-available?

If you are someone who has a huge fear of shots—like, if that is the difference between you getting the vaccine and not getting the vaccine, then sure, absolutely. Hold out, sure.

But the likelihood is—you know, the Moderna vaccine, because it’s two shots, and because it does require some refrigeration, or the Pfizer, because it requires special freezers, I think those will be made available in areas where the infrastructure exists, or where the infrastructure can be built relatively easily. And you're going to see the Johnson & Johnson vaccine distributed more widely in rural areas, places that are pharmacy deserts, or healthcare deserts. And also probably even within, like, urban settings. Maybe if you go to a community pharmacy, I can see maybe the Johnson & Johnson one being distributed more than say, the Pfizer or the Moderna.

I do live in a rural area! My concern with the Pfizer one—and I picked this up from a contractor guy who rocked my world with it over the summer—is the question of whether it’s gonna make my arm freeze solid like the T-1000 when they inject it. That’s, uhh, not likely, yeah?

[a look of befuddlement]

My understanding of the Pfizer one is that it is stored at these very, very cold temperatures, but when they're preparing it for you, it is thawed, and placed in refrigerators that are at temperatures more familiar to us: between 36 degrees and 46 degrees Fahrenheit (that's two to eight degrees Celsius). But it's not entering your arm at painful or dangerous sub-zero temperatures.

OK, that makes me feel somewhat more secure. I will pass that to the contractor.

You might not be young enough to have gotten the chickenpox vaccine. But, you know, any of the childhood vaccinations I would just ask, did any of those feel like they were at, like, negative degrees? I think sometimes it's just, like, asking people to think about the questions that they're asking.

There was this thing on, I think it was CBS News, I’m blanking on the reporter’s name but he went to North Dakota and was interviewing people going into bars. They’re doing their normal Thursday night, Friday night, Saturday night kind of thing, going out. There were these two women, one of them actually happened to be a nurse. And he asked, you know, “What are you gonna do tonight?” They're like, “Oh, we're getting ready to go into this bar and hear this music.” And he's asking, “You're gonna go do that, in the midst of this pandemic, even knowing that you may get COVID?”

And then he asked the one that's the nurse, “What do you do?” She said, “I'm a nurse.” She works in the COVID ward. And in talking through this, you could see that they were like, well, this isn't really a good idea. He did say he followed up and said that after the interview, they decided it just wasn't worth it, and they went home. That happened more than once, when he was out in the field, interviewing people, you know, about going to bars and restaurants and whatever else.

And it's like, when you get people sort of, in dialogue, asking questions, and then you ask them to sort of think about things, then they start to understand what does and doesn't make a lot of sense.

Hmm. That makes me feel somewhat bad about asking you what would happen if I mixed all the many vaccines in a Big Gulp cup and then just chugged it down.

Probably nothing good! Um, we don’t have an exact answer on that. We haven’t asked Dr. Fauci about that one.

But as far as you know, I should definitely not consume a delicious cocktail made of all available vaccines.

You should not make a cocktail of all the vaccines, no. And you should not for your first shot get Pfizer and then for your second shot go get, for example, the Moderna. Stay with your brands! If you’re a Gucci person, stay with Gucci! If you’re a Prada, stay with Prada!