In 2018, a question burned in the minds of six pediatric healthcare professionals: How long does it take for a small ingested object to pass through a child's digestive system? Unwilling to ask actual children to experimentally swallow a foreign object, these skilled workers volunteered their own gastrointestinal tracts for science, and published a paper detailing their experiment in the Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, which went viral in a way that papers published in the Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health usually do not. On that fateful day, on opposite sides of the globe in the United Kingdom and Australia, the six each swallowed a Lego head and waited for the plastic noggins to meander through their large intestines and emerge, triumphant, in a toilet bowl. Five of the pediatricians recovered their Lego heads in a matter of days. One pediatrician never recovered his Lego head. This is their story.

It all started with one pediatrician at a conference, wishing more people had come to his lecture. Andrew "Andy" Tagg was speaking to an audience at a local children's hospital in Australia. He decided to talk about about the danger of swallowing or ingesting foreign bodies, a topic he'd chosen as a way to talk about recent high-profile cases involving children swallowing button batteries. The tiny batteries can get stuck in and severely burn the esophagus within two hours, which can lead to major injury or death.

Dr. Andrew Tagg (emergency physician with a special interest in pediatrics): I was super-prepared for this. I started my talk by talking about how some kids come in and they swallowed worms from the garden, and I'd give out gummy worms to people in the end. I did a lot of research, because I'm the sort of people who nerds out and likes to read all the primary-source literature. There were 300 people at the event, but maybe only 15 were at my talk, in a little side room. And then by the end of my talk, there were only 10 people. I thought, all this huge amount of work, I wish I could do something more with it. So I turned it into a blog post for Don't Forget the Bubbles.

Dr. Henry Goldstein (adolescent and young adult physician and general pediatrician on Queensland's Gold Coast): We founded The Bubbles in 2013. The four founders—Tessa, Ben Lawton, who didn't have a part in this paper, and Andy and I—hadn't met face to face until 2017. We'd run this website, and subsequently a conference, entirely online. Our mission was to help anybody who cares for children to make meaning of information in pediatric care. We would read the primary papers, and our goal is still to direct people back to that primary literature, but to interpret it in a way that kind of cognitively offloads a lot of the low quality or impenetrable writing that science offers us. To give it to people straight. And say, actually, "this is what you need to learn from this."

There's these ginormous studies that change the world and change clinical science, and we're exposed to those early on after the publication, and they change practice. But actually, a fair whack of medicine is learned at the bedside. And our profession is inherently based on an apprenticeship model, where you can talk through a case with one of your [senior colleagues] and they challenge you. Those little corridor conversations or bedside conversations or conversations at nurse's station every couple weeks—that's really how most of medicine is learned. So right at the start when we first wanted to put together The Bubbles, it was on that premise.

All of us in our work in pediatrics, and certainly a pediatric emergency, had had met these parents, who, after a month, would bring their child and say, "I've checked through every single one of my kids' posts for a month, and I can't find this thing." That's yuck! And it's classic. It's just what caring, loving parents do, who are very, very worried.

Dr. Katie Knight (pediatric emergency medicine consultant at North Middlesex Hospital): Probably every other shift you work, someone comes in having swallowed something.

Andy: We know that number one ingested foreign body in children are coins. They're the things that kids swallow. They put them in their mouths just see what happens. Number two was plastic toys. I was thinking, plastic, what does that actually mean? And then I remembered back to when I was a kid, and I would try and bite open those little bits of Legos that are stuck together and I couldn't get them apart. I had definitely swallowed a Lego as a child. I thought, well, there's no real data about how long it takes Lego to go through. There's data about how long it takes coins to go through. It'd be really interesting to see how long it took to go through. I wondered if I could convince some of my friends to take it.

Henry: [Poo] is not the bodily fluid that grosses me out the most. I think snot does, actually. Those deep-throat hocks. That stuff clags up airways and can be a life threat that you're going to have to manage. Because you can hear the gurgling, and you're thinking, oh gosh, oh, please don't block your airway. Whereas someone pooing? Pooing is normal. Everybody poos.

Dr. Damian Roland (honorary professor and pediatric emergency medicine consultant, Leicester Hospitals and University): I've been shown loads of poo. That's a really common thing to be shown, because parents get worried about poo all the time. So I've seen lots of poo, but I've never had to look through it myself.

Lovely piece of work 😉. As I child, we had a single piece of Lego with the number ‘7’ upon it. It was used for every house built. It had been thru my, and my siblings (totalling 4), guts at least once each. If only this research had been done in the 70s. #poorparents

— Simon Whittaker (@bluesaint72) November 23, 2018

The pediatricians weren't just in it for the poo; they had an ulterior motive: to be published in the Onion of pediatric journal issues. One of the world's oldest general medical journals, The BMJ (formerly the British Medical Journal) is prestigious, peer-reviewed, and generally very serious. But at the end of each year, the journal publishes an discerningly goofy Christmas issue. One paper in the 2017 issue investigated whether Doctor Brown Bear, the GP on Peppa Pig, contributes to unrealistic expectations of primary care in his practice, such as the time Doctor Brown Bear turned on the sirens of an emergency vehicle on his way to see a 3-year-old pony who had coughed three times. Getting published in the Christmas BMJ is a bit of a milestone—a sign that you can save lives and also make people laugh. When Tagg pitched the idea during one of the group's remote meetings—of everyone swallowing a Lego and seeing how long it would take for the plastic to pass through poo—no one batted an eye.

Dr. Tessa Davis (consultant in pediatric emergency medicine at the Royal London Hospital and a senior lecturer at Queen Mary University of London): I read the BMJ every week, and I love the Christmas edition. I've had a longstanding career goal to get into the Christmas BMJ.

Katie: It's a bit of a legendary thing within the medical community.

Andy: A part of me thought, well maybe I could do something around Paw Patrol and how awful they are at responding to real emergencies. But then I thought that was gonna be far too complicated and far too hard to do.

Damian: We were looking for a good idea. We were trying to do something which perhaps hadn't been done before, and might have some tangible benefit.

Henry: There was this kind of pause in the conversation. And then Andy says, "Actually, I'm going to put an idea forward, and it's probably a bit yuck. There's a bit of poo involved. But I want you to hear me out."

Tessa: I loved it.

Damian: We just thought that was brilliant.

Katie: I thought it was quite a crazy idea, as you can imagine. But coming from the people who I knew who were involved, I knew they were on to something—something interesting, at least.

Henry: Over the next two weeks, we hashed out exactly what the protocol was going to be.

We would swallow them at a particular time, and we talked about whether that would be a time of day or a GMT time, and decided that most appropriate would be at the same time of day. We would do a stool diary sort of for three days in advance, to see if the Lego head would change our pattern of stooling. The normal range of stooling can be three times a day or once every three days, and some people are farther apart than that. So we wanted to have that for our participants.

Damian: If you only pooed every three days, then that actually that would bias the results, because you'd only be able to find it in three days. Whereas if you pooed twice a day, then clearly it would be unfair. I came up with this thing called the stool hardness and transit time. The idea was that what we would measure for a couple of days before we swallowed it was the stool hardness scale and how often we went, and we would do it after as well, to make sure we were all pooing at the same frequency. I thought that would add a bit more science to it.

Henry: I came up with the acronyms kind of on the spot, about the Stool Hardness and Transit (SHAT) test and the Found and Retrieved Time (FART).

We had this long discussion about the most effective way to find the Lego head. I would say we had pages and pages and pages of communication, which easily could have been an entire other paper on what is the most effective way to catch a poo. For pediatricians, that's actually a really significant thing, because we collect poo samples all the time. But we actually decided not to put that in the paper because it ran counter to the overall message, which is don't look through your poo. This is like little trove of knowledge that's kind of sitting back there in the past waiting for a moment to publish.

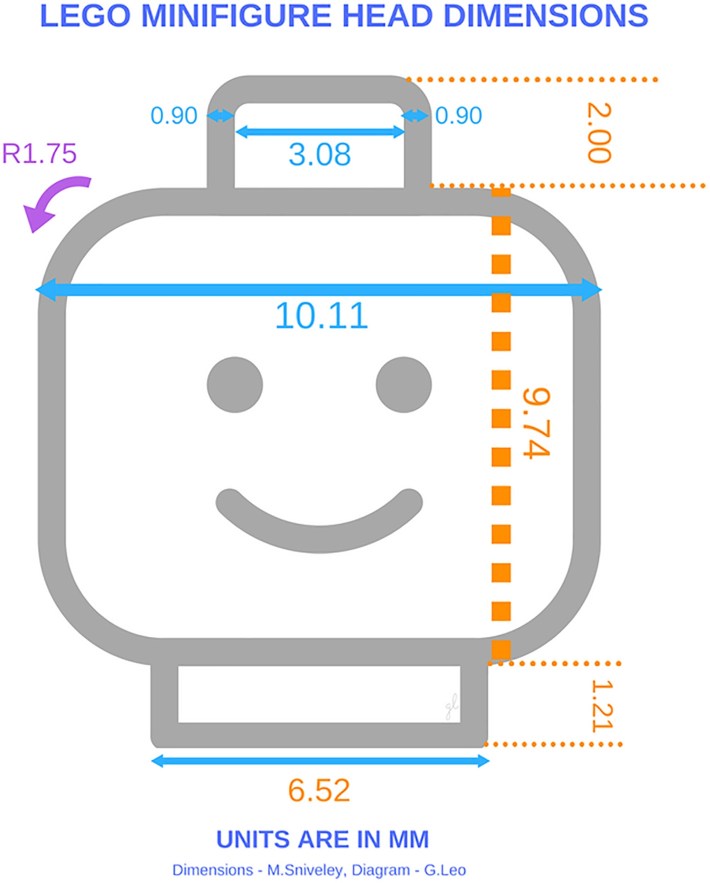

Henry: We get people to swallow pill cameras all the time in our gastro department, and they're bigger than that. The numbers that we'd learned, although I'd learned as part of my pediatric training around what you will and won't pass and where the danger zones are, is that if something's greater than 110 millimeters, then it won't get around your duodenum. And if it's pointy and spiky, then there's a risk of it stabbing into stuff. The Lego heads were neither of those. We've kind of talked about that right at the point of designing the study because we talked about swallowing the classic two-by-four Lego brick, and then decided that that was going to be too pointy. Really, a Lego head is just like a piece of corn, isn't it?

Andy: We decided we could just do a waiver of consent, because we're all just doing it to ourselves, as opposed to trying to get ethics approval for doing it to our children. In the same way that you know, Barry Marshall swallowed Helicobacter just to find out if it would give him stomach ulcers, we just thought we'd just carry on and do the same sort of thing.

The swallowing commenced between 7 a.m. and 9 a.m.—morning wherever they were in the world—and then the search began in earnest. The six pediatric healthcare professionals, including pediatric doctor Grace Leo, then went about their days as if nothing had changed, as if there was no tiny plastic head beginning its epic voyage through their guts and into the colon. One member of the group was excused from participation to ensure he would not need to search his poo from an airplane lavatory—the least desirable kind of mile-high club.

Ben Lawton (co-founder of Don't Forget the Bubbles): There is 30 hours of travel time between my house and my parents house, it wasn’t really practical.

Henry: Three days in advance, we're like, "OK, we're gonna start doing a stool diary now." There's this, like, mounting excitement. And then someone goes, "Oh make sure you record yourself swallowing the Lego as proof for each other." I made sure that I'd done a poo beforehand, because we'd agreed that you have to check through every poo after you swallow that Lego.

We discussed at the study design phase about mitigating the risk of corn in our diets—acknowledging the risk of a false positive.

Andy: I don't think anyone specifically went out to buy Lego heads to find which was the tastiest looking one to have. It was much more of a case of which head had the best-looking face to swallow. You want one that looks kind of shocked and scared as it goes down.

Katie: Tessa's children had a big bag of Lego heads, so she brought in some heads for us. My head had a bit of a grimace, which was a bit appropriate.

Tessa: I have three children of my own. I probably have about five billion of them floating around. There's literally just a bag of floating body parts.

Henry: It felt like swallowing something marble-sized. It was firmer than I would have expected.

Andy: We just carried on with life as normal. Well, life as normal except for searching through the toilet. We had a Slack channel that we were using just to communicate how we were going, making sure no one was suffering with horrendous stomach pains or diarrhea or anything else like that. It was much more of an anticipation of who was going to be the first person to find it. It's like waiting for Christmas or hunting for Easter eggs.

The pediatric healthcare professionals did not agree on a single strategy for retrieving the Lego head, opening up the field to innovation.

Tessa: In hospitals, we've got these cardboard bowls. I basically mashed up the poo to try and find the Lego head. It was really disgusting. Thankfully mine was in my second poo.

Katie: I thought a lot about the strategy because I didn't want to miss it and keep searching. So I came up with the idea that the best thing to do to minimize the mess and just the grossness of it was to put the sample in a Ziploc bag, so it was all sealed but the bag was see-through. You could push around to find the Lego head. I took a vomit bowl from the hospital, pooped into that, and transferred it into the bag.

Luckily, I found mine the first time I searched, within 14 hours. I was quite surprised to be honest. I didn't think it would get through that quickly. I felt relief I wouldn't have to do it again.

Andy: For me, it was very much a case of looking and then squishing through the poo. So going to the toilet normally. I used one of those wooden tongue depressors.

I hadn't known I'd passed it. It wasn't like I felt it go "oop!" and then squeak out. But it was very satisfying to see. It took two days for me. I didn't have to keep on going on searching my poo anymore. Once it was out, that was it. I could forget about it.

Henry: The first attempt was incredibly messy. I had been taught as a junior that the way to collect stool was to—which you're going to scoop off and sieve for sampling—is that you put an ice cream bucket in your toilet. In Australia, we have [low-flow] toilets, so you don't have to catch it really up high. There's only this much water. So you put one of those square, two-liter ice cream containers. And the poo goes there. And I thought ah, maybe what will make that easier would be if we put it through a sieve. So I had set it up so that I could poo into the sieve and then have a way of like using a plastic bag like a glove to search. I made a hell of a mess.

I committed our family's best flour sieve, which is plastic and metal. I broke the handle off and wedged it into the bowl and decided that I was going to use chopsticks to search through. That's the classic mistake because as we all know from stepping in a dog poo it doesn't smell that bad until you break it, and so things got gross. So I searched through and then couldn't find it and took it out and was like, "Oh, this wonderful baking sieve is covered in poo. I'm not going to use this again." There was some unhappiness about using the sieve. It was a good sieve.

At the time I was the chief medical registrar, which is like the most senior junior doctor at my hospital, which is the biggest training institution for pediatricians in Queensland and in Australia. No one knew that I was doing this study, so I had to go and find the right toilet far enough away from everything else, and I had to rework my strategy in the meantime. I was a suit and tie guy at that point. I knew that it was coming. I had a reasonable break in not too many meetings. I got the vomit bag. And the South Australian Health had a really nice diagram about how to put poo into a vault pack. I did that; it was kind of awkward. I managed to catch it all, twisted it up, and sort of squeezed through, and I knew there was nothing firm enough in there to equal a Lego head. And then I was like, "Oh no, I've got a vomit bag full of poo. I cannot flush a vomit bag. And there's no rubbish bin in this toilet. What am I going to do now?" I had to shove the poo down the toilet, twist the vomit bag up, wrap it in another one, take it out to the clinical toxic waste pile, walking through the hospital in a suit and tie, trying to walk as short a distance as possible. And I wasn't near the gastroenterology department so I had no reason for a poo smell. And then I washed my hands, straightened my tie, and got back to work.

The third poo was at home. I went straight into the vomit bag, feeling like an old pro at this point. I caught it. I think I just looked and saw it there. It was sitting right there at the top, and I thought, "Oh this is fantastic. I'm not going to have to get the chopsticks out and have a feel-through." I think I might be one of the only in the group who actually took a photo of successful retrieval. I don't know if I still have that photo, but I did take a photo and send it to the group as proof of saying "First!" I was absolutely stoked that it happened so quickly, but I also kind of put it as a warning to the other guys to say, "Hey, check your early ones, because this happens faster than you think."

Damian: Yes. I remember that. The interesting thing is that I kind of thought it had proved my approach that you didn't need to search through it. It should just be there.

After five of the six pediatric healthcare professionals had gone to extraordinary lengths to find and rescue their excreted Legos, all eyes turned to the sixth, whose Lego was nowhere to be found.

Tessa: We all just started saying we'd found ours. And eventually, we realized that Damian was still looking and it was getting on a few days.

Katie: Damian was sending increasingly desperate messages: "You guys, I'm still doing this, when can I stop." I think we were finding it quite amusing.

Henry: He goes, "I'm still searching. Do I have to keep searching? How long should I search for?" And we said, oh, probably 14 days is reasonable.

Tessa: For the first few days, we thought maybe it could still be in there. Because obviously we didn't know how long it would take.

Damian: It turns out my colleagues did a proper, like, break open the poo and see if it was there. Clearly I'd not been that enthusiastic or that diligent. I kind of looked at it, maybe prodded it around, but I certainly wasn't going to open up the poo to see if it was inside.

I don't remember people declaring what their chosen Lego head search would be. In fact, perhaps had we done that maybe I would have made more effort. Because I presumed everyone was doing what I was doing. It absolutely shocked me when I found out that people were searching their own poo.

I'll hold my hands up and confess that I never really did.

Tessa: He's been fully punished, because he just didn't look properly. And that's what happens when you don't look properly.

Henry: It was his reflection that he might not have looked adequately over the first couple of motions, which is regrettable.

It's one of my frustrations with the study, is that we have a very high suspicion that he passed it early. But the interpretation is that it was not found and therefore could still be inside him, which is the exact opposite of the core message that we wanted to deliver.

In the end, Katie and Grace found their Lego heads in their very first poos. Tessa found her Lego in her second poo, on the second day after swallowing. Henry found his in his third poo, on the second day. Andy found his in his third poo, on day three. After two weeks of peeking at his poos, Damian concluded his futile search, finally freeing the pediatricians to write up the study. They all piled into a Google Doc one night to bang the paper out. Once it was finished, they submitted it to the journal of their dreams, the dream that spawned the days of sifting and searching through feces, the legendary Christmas BMJ.

Andy: The Christmas BMJ said no outright.

Tessa: They don't allow self-experimentation.

Andy: We actually got rejected six times from different journals.

Henry: Rejection is just part of academic writing.

Damian: We were a bit worried that it wasn't going to get published anywhere.

Henry: We started off as a website. We do blogs. We could have put this on our own blog, and we could have just left it at that.

Katie: Tessa was the main author who was in charge of submissions. She was very tenacious when it came to finding somewhere that would accept it.

All our conversations, right down to the intricacies of how to search a poo and taking the time and doing good enough quality research, we knew that we had something that was worth publishing.

Andy: We went for the Christmas BMJ, the MJA, Medical Journal of Australia, and then another three or four different journals until Journal of Pediatrics and Child Health said, Yeah, go on then. Not because we were hassling them! But because they thought it was funny. And quite rightly so. It was the most widely read and quoted paper of the year.

Tessa: I've had various Twitter threads and things go viral. But honestly, the news cycle, it went through every media and news outlet I could think of over the course of a week, and it just escalated, escalated, escalated. And it was everywhere, literally everywhere you could think about it, it was there. It culminated in James Corden and Jimmy Fallon using it in their opening monologues of their shows making a joke about it.

Katie: It was kind of mad. It just kind of blew up out of nowhere.

Andy: That was the best thing ever. You know for us, who are really just a group of normal people, hearing this, it just made our day.

Damian: Andy Tagg was on the Melbourne news. Someone from the BBC contacted me, and this to me was the biggest unintended consequence: I had one of their digital teams came out, and we did a little interview in the hospital. But there I was able to talk about, yes, love Lego heads are a bit fun, but actually, swallowing a button battery is really serious. And actually, this is something that you need to take very seriously.

That's what I'm most pleased about. We managed to get an important public health message out on the back of this.

Andy: I emailed [the marketing people at LEGO Group] but never got anything back, probably because they didn't want necessarily to be associated with people swallowing Legos.

Jennifer MacDonald (Director of Communications, Americas, at the LEGO Group): The study came out four years ago in 2018 for a special Christmas edition of the Journal of Pediatrics and Child Health but the LEGO Group wasn’t involved in putting it together.

Henry: I've worked in three or four different teams since the study, and occasionally people will say, "Why do you have that Lego thing on you?" And then, occasionally, someone will say, "Ah, he did that Lego study."

Katie: Even the other day, I had a small child who swallowed a small bit of plastic. I could say to the parent I did take part in this experiment one time, and I can tell you it will pass very quickly. You don't need to be concerned.

Damian: I've been brought various kinds of Lego items. My lanyard is lots of Lego heads at work because someone brought me that as a present. I'm the doctor who couldn't find their Lego head.

I'm now a now a professor of pediatric emergency medicine, I have a quite large research portfolio. For what it's worth, I'm probably one of the leading children's emergency medicine researchers in the UK. But the research that has probably had the most impact is this, out all the stuff that I've done. I'm not sure how I feel about that. But if I go to my deathbed, and this is my most important contribution to science, well maybe that's not such a bad thing.