Anchor Brewing was a cockroach. The San Francisco brewery survived the great earthquake of 1906, the subsequent fire that destroyed the city, its owner being run over by a cable car right after the fire, World War I, the Volstead Act, World War II, a series of midcentury closures and re-openings, and 127 years of foundational changes to both the social geography of the Bay Area and the American beer-drinking palate, until Anchor finally met a foe it could not outlast. The Japanese brewing giant Sapporo purchased Anchor in 2017, and on Wednesday, they gathered workers at the company's Portrero Hill offices and told them that after six years of disastrous leadership, the company would be liquidated. Vinepair's Dave Infante reported that the company had been scrambling to find a buyer, and absent a last-second deal, Anchor will be shuttered and stripped for parts. You used to be able to get an Anchor Steam at any bar in San Francisco, but those days are over. The oldest operating craft brewery in the United States is dead.

It is tempting to read this as another grim story about the pandemic claiming a beloved business, given an extra bit of apocalyptic flair by the degree to which Anchor is synonymous with San Francisco. In that light, the death of one of the city's most iconic companies goes hand in hand with the narrative that San Francisco is a dying city riven by the tripartite scourges of unchecked crime, spiraling unaffordability, and, uh, wokeness. Even if you don't want to go that far, you can correlate San Francisco's high office space vacancy rates, declining national craft beer sales, and "inflation," and conclude that this economy was too harsh for Anchor to survive in. Indeed, how can any small business keep its lights on under such conditions? That is the story Sapporo's PR goons are selling and the San Francisco Chronicle is buying, without any pushback or worker perspective, even though it's not true. Economic conditions matter, though they aren't nearly as relevant to the Anchor story as Sapporo's uniquely catastrophic stewardship of the company.

after i heard they were ceasing all operations this morning, rode my bike by anchor brewing on the way to work. the flag is flying upside down.

— Grant Marek (@Grant_Marek) July 12, 2023

dark, dark day for san francisco beer drinkers. pic.twitter.com/0UL5xyAWHT

Like Levi's, perhaps the most famous San Francisco company, Anchor was a picks-and-shovels Gold Rush venture founded by German immigrants. The company traces its early history to a "beer-and-billiards" hall opened by Gottlieb Brekle in 1871, though it would be 25 more years until the father and son-in-law duo of Ernst F. Baruth and Otto Schinkel Jr. bought the brewery and slapped the Anchor name on it. As luck would have it, Baruth died suddenly shortly before San Francisco burned down in 1906 and Schnikel Jr. was killed by a cable car right before the brewery reopened a year later.

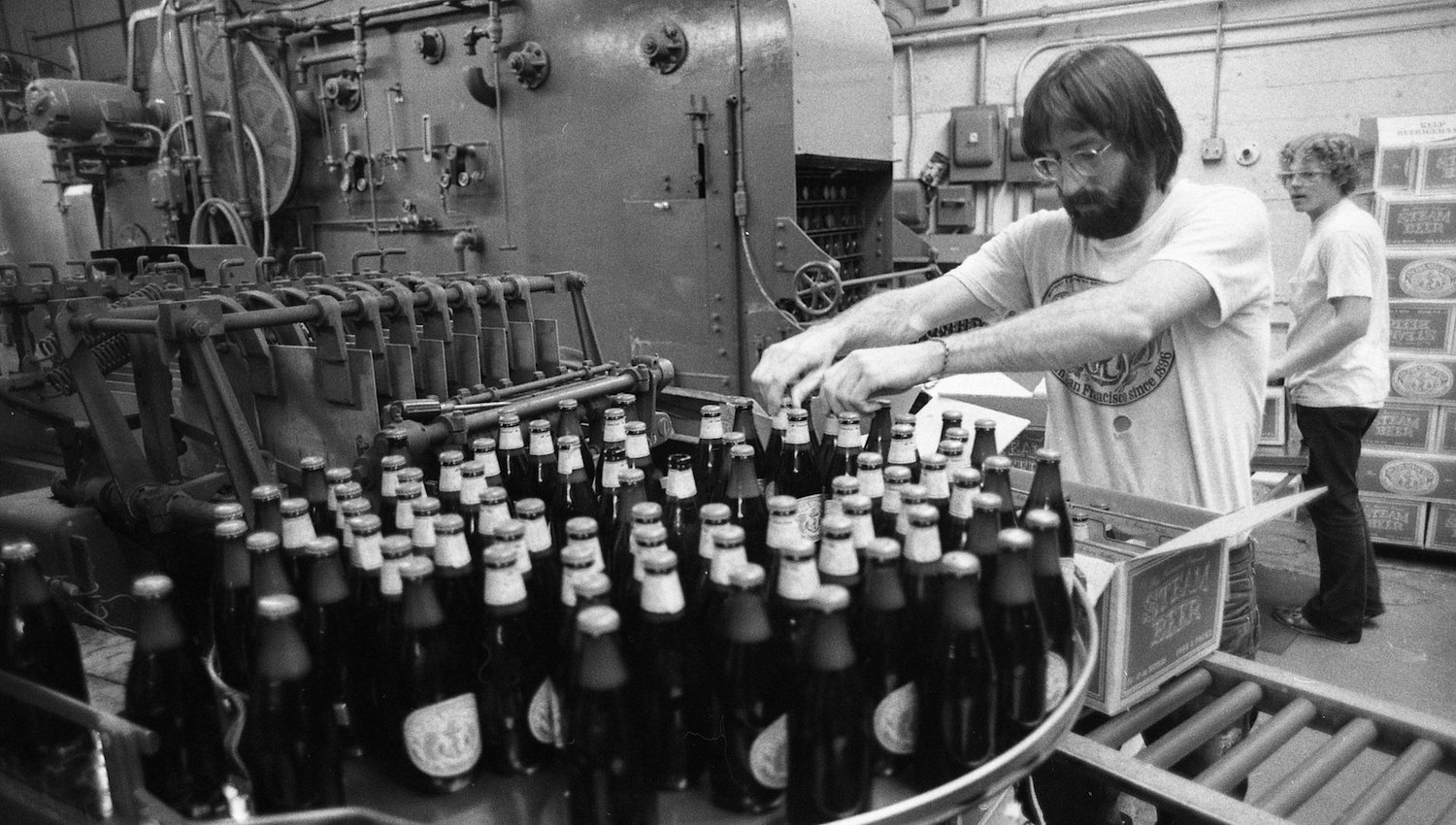

There's no record of what happened during prohibition (probably they just kept selling beer), though the brewery burnt down again less than a year after Prohibition was repealed in 1933. Under Joe Kraus's leadership, Anchor hobbled along through the war, but aging equipment, Kraus's death in 1952, and some really nasty brews forced it to briefly close in 1959, before some guy bought it in 1960, lasting five years before he was on the verge of closing it for good. That's when Fritz Maytag—yes, one of those Maytags—had his first Anchor Steam at the Old Spaghetti Factory, which inspired him to take over the brewery and establish it as a fixture when it was at risk of permanent closure in 1965. Under Maytag's careful leadership and with his considerable investment in new equipment, Anchor boomed, establishing itself as one of the premier craft breweries in the United States by the 1970s.

The brewery is most famous for its signature "steam" beer—tons of Bay Area locals still call the company Anchor Steam Brewing—of which Jack London was a fan and which is a reasonably distinct as a style. It's named (probably) for the rooftop vats that the company used to cool the wort in the cold San Francisco air, and it pours darker (a robust amber) than it tastes (nutty and rich, with a frisson of opening bitterness). Maytag was a "stickler" for quality, and he never used artificial carbonation, insisted on barley malt and real hops instead of corn slurry and other extracts, and didn't sell to distributors that wouldn't keep the beer cold in transit. Anchor made a few other good beers, staying away from the truly hoppy stuff but producing one of the first domestic barleywines and a killer porter, though the brewery is probably second-best known for its Christmas Ale.

Anchor began brewing the dark spiced brew, officially called Our Special Ale, in 1975. The vague shape of the beer was always the same, yet the particular recipe changed every year, along with the hand-drawn tree on each year's label (Jim Stitt did it every year until 2021). The arrival of the Christmas Ale on shelves and in bars in the Bay Area was always the surest sign that the winter holidays were upon us, and my partner's uncle Todd would always bring a magnum to holiday parties. But Anchor announced in June that they would not be producing this year's Christmas Ale, and would cease distribution outside of California.

That was the last, most ominous sign that Anchor was in trouble before today's closure announcement, though trouble had been—sorry—brewing since Sapporo took over. Maytag sold Anchor to a couple of Skyy Vodka guys in 2010, who then sold it to Sapporo seven years later after plans to dramatically expand brewing operations with a huge new facility near Pier 48 went kaput. Sapporo was always a strange owner. The Japanese giant owns very few foreign breweries, and established the subsidiary Sapporo USA exclusively to operate Anchor (they also bought San Diego's Stone Brewing last year). Maytag had kept salaries high, but new ownership slashed hourly wages, to the point that Sapporo was paying minimum wages and some full-time employees were earning $40,000 per year, an impossible salary to live on in San Francisco. So the brewery unionized with the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, and they became the nation's first union craft brewery when they ratified their contract in December 2019.

Anchor's place within the city was long established by then, though the union drive drove home exactly how important the brewery was. Every bar posted signs in their windows in support of the Anchor Union, organizers and union reps were treated like celebrities when they showed up to drink-ins or other public outreach events, and the city rallied behind the union to a truly inspiring degree. Then the pandemic hit, and Sapporo bumbled their way through it like morons. First, they used the occasion to install a bunch of prohibitively expensive automation equipment (a former union organizer said the new robots dramatically decreased the amount of beer Anchor could produce, by as much as 60 percent), and then came the rebrand. Clearly Sapporo paid a bunch of design consultant types to tell them that they should streamline and blandify their logo for frictionless consumer identification and peak modularity, though it still baffles that they would ditch their instantly recognizable old-timey anchor logo to become Twisted Tea.

According to Infante (who really has been all over this story), local craft brew giants Russian River and Sierra Nevada briefly sniffed around a sale, but whatever deal may have been in place fell apart. Workers at Anchor have been screwed over by Sapporo since they bought Anchor, and over the last few years, Sapporo slashed the workforce from 85 to 61 and eliminated the entire sales department. When they announced the discontinuation of the Christmas Ale, they cited costs, though they neglected to mention that they had already bought all the ingredients needed to make the seasonal beer.

The Anchor statement crafted by crisis PR guy Sam Singer, which forms the outline of the Chronicle story (the Chronicle is also a Singer client), expresses admiration for the company's history before sighing that "the impacts of the pandemic, inflation—especially in San Francisco—and a highly competitive market left us with no choice but to make this sad decision." While the craft brewing industry has contracted around the edges, none of the breweries that have shuttered in the past two years have been subject to the same harmful meddling from a corporate parent. The "unprecedented economic times" argument doesn't hold water for a company like Sapporo that spent its brief, ignominious ownership haranguing its workers and flailing wildly from bad idea to worse.

Read any account of the company under Maytag, tales from the union drive, or even Infante's latter-day reporting and it's clear that Anchor's workforce has always viewed the beer with a real reverence, and why wouldn't they? When Anthony Bourdain visited to film No Reservations in 2009, he left charmed after discovering that San Francisco was not the hoity-toity enclave he feared, but rather a "beer for breakfast" town. That beer was undoubtedly Anchor Steam, which is now as dead as that loving vision of the city is.