It’s almost time for the 2022 World Cup. To help get you ready, we will be providing you with precious information about every team in the tournament. You can read all of our World Cup previews here.

The United States' tortured soccer history is the story of one of the most obvious problems in international sports not being solved. By sheer force of demographics, money, and general sports culture, the United States should be one of the best international soccer teams in the world. Instead, they have won exactly one World Cup knockout round game since the first-ever tournament in 1930 and have a negative-25 goal difference at the tournament. If you don't closely follow soccer, this incongruity might not make much sense, especially when one considers the dominance of the U.S. women's national team or how well the U.S. fares at the Olympics.

Even as a fan of the USMNT, I must admit there's something beautiful about the team's inability to fall backwards into a World Cup, especially when considering how scattershot the U.S. soccer system has been for decades. U.S. soccer should not have been validated for prioritizing the college game and running MLS like a carnival show with penalty kicks at the end of draws, and the fact that it has taken them this long to become—well, whatever they are now; good, maybe—suggests something beguiling, something elemental about what suite of factors produces the best soccer in the world. The discrepancy suggests the almost tautological notion that to succeed on the international stage, a country must be a true soccer nation. It suggests that the skills it takes to become the best player in the world cannot be taught, they can only be learned. It's no coincidence that this current U.S. team, one of the youngest in the tournament, looks like one of the better USMNTs while it's stocked with the first generation of players who've come up within something resembling a normal soccer development track.

This is not to say the U.S. has never had good players. Brian McBride, Clint Dempsey, and plenty of other stars of yore could play for this current team in their primes. There has long been a steady flow of Americans traveling eastward across the Atlantic. The difference now is that players are going over to Europe in significantly larger numbers, and at significantly younger ages than ever before. (For more on this, there's a whole series.)

There's something fundamentally different about the program now, and I can assure you the flow of well-regarded prospects is only picking up. Yet the rarity and brutal difficulty of World Cups is such that that seismic level of improvement may not manifest itself in meaningfully better World Cup results for some time, and maybe not even ever. What good are 50 European-level players if none of them are as good as Antoine Griezmann?

This team here is at the vanguard, and they're in a tough group, and they looked like shit the last time we saw them all together. They can and should be gunning to beat England, win the group, and pull off an upset in the knockout rounds, but also, a group-stage exit would not be a ludicrous outlier outcome. The most exhilarating thing about this team is that their window of possibility is thrown wide open. Yet, despite their youth, the expectations are serious. A team full of players in their early-20s, almost none of whom were in the program when the USMNT lost to Trinidad & Tobago in 2017 to crash out of qualification, have a good deal of pressure on their shoulders, none more than . . .

Who Is Their Main Guy?

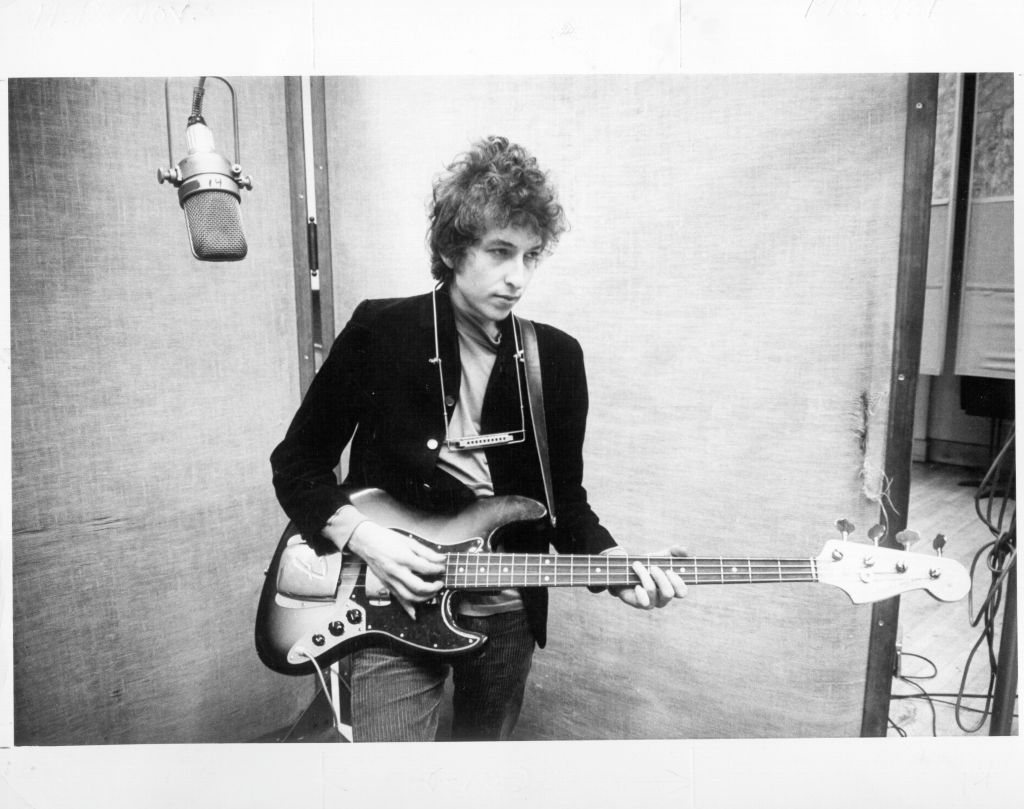

. . . Christian Pulisic. If you know one player on this team, you know Pulisic. His face is on every advertisement for the World Cup. He plays for Chelsea, one of the most popular teams in the world, and he won the biggest competition in club soccer with them. He has also been on the national team for a deceptively long time, playing eight seasons as a professional, debuting for the USMNT in 2016 as an 18-year-old, earning the captain's armband two years later, and surviving as the only real remaining bridge piece from the accursed Bruce Arena teams. He has been the future of U.S. Soccer for so long that it's easy to forget that he is now its present, playing in the prime of his career, set to take the stage at a World Cup for the first time. There is real pressure on him to deliver, given the failures of 2018, Pulisic's own murky club future, and the zeal with which he has taken up the mantle and eagerly said: This is my team, we won't back down, and we are here to win.

As for that club form, Pulisic swapped the chill, sane situation at Borussia Dortmund for the circus of Chelsea in 2019. He has had genuinely transcendent moments as a Premier League attacker, scoring in the Champions League at Real Madrid, distinguishing himself as Chelsea's youngest-ever hat trick-scorer, and nearly finishing off a spectacular move in the UCL final. Pulisic has shown that, when he is on his game, he is a world-elite left-winger, capable of starting and finishing scoring moves and providing a constant sense of danger.

He has also struggled to stay healthy and cement his spot in the starting lineup even when healthy. The thing about a club like Chelsea is that always have what feels like seven (or more) players for four (or fewer) spots, a state of ferocious, internecine competitiveness that greatly rewards success and quickly churns out plenty of very good players who, for whatever reason or for no reason at all, didn't produce enough. Pulisic found himself buried down the depth chart late in the Thomas Tuchel era, and is currently fighting for a place in Graham Potter's rotation. His versatility works against him here, as he's started two games as a right wingback, which, if you know how soccer fields are set up, is the opposite of his preferred position. That doesn't mean his failures are not his own. Pulisic hasn't been at his peak in a while. He might leave the club soon.

The good news for United States fans is that Pulisic seems to be healthy and he consistently shows out in a U.S. shirt. He gets to be on the ball as much as he wants, and he has a habit of doing disgusting things with it. The U.S. is at its best when it runs through Pulisic and when it supports him so that he doesn't have to track back to put out fires. Tyler Adams is the team's most tactically critical player (see below), Sergiño Dest its most likely to score the goal of the tournament, Gio Reyna its best prospect and maybe best player, but Christian Pulisic is its heart.

Who Is Their Main Scoring Guy?

Who's actually going to score the actual goals? is, like, the operative question about the USMNT. Their whole thing is having one million strikers, all of whom are equally flawed in unique ways, and thus they don't really have one "main guy" who "will" score goals. So rather than focus on that, let's turn our attention to the midfield.

Under Gregg Berhalter, the USMNT has solidified into a team that plays a 4-3-3 with both fullbacks dedicated to springing forward. That necessarily involves leaving both center backs to cover more space than most teams would feel comfortable with, thus the USMNT's formation is essentially a gambit. The bet is that Tyler Adams, Weston McKennie, and Yunus Musah can do the work of four men, that Musah can bust the lines with his running, McKennie's ability to push out wide can overload the attack at the right time, and that Adams will snuff out attacks before they even start by running everywhere.

McKennie scores goals from set pieces because he's such a good athlete, but the goal of this group is facilitate the bucket-getters up front. If McKennie can't go (it'll be close), Berhalter faces some uncertainty, though both Gio Reyna and Brenden Aaronson can ball out from the midfield. So, while the team may be forced into some minor structural changes, the foundation remains the same. Adams and Musah are still the bedrock of the midfield, and a true passer's passer (Reyna) or an all-action shit-stirrer (Aaronson) ahead of them fits in very well.

Where's The Beef?

Which teams or players does the United States not like? Do the USMNT's players like each other? We investigate the United States' potential enemies.

"When you're the top dog," Charles Barkley once said, "everyone wants to put you in the pound." The USMNT is not the top dog, yet everyone still wants to put them in the pound, because the jersey reads United States. Maybe your country had its democratically elected government overthrown by the U.S. State Department between 1950 and 2022, as U.S. group-mates Iran did in 1953; if they didn't do so, probably they tried at some point. Maybe you, a soccer nation with a rich history, resent the up-jumpedness of a team whose talismanic best player is a rotation piece for Chelsea and is still conceived of by his home nation as God's Honest Truth. Maybe you think the uniforms are stupid. Maybe the U.S. yoinked one of your dual nationals and you hate the inexorable gravity of money. Maybe you are a fan of Mexico and you think the the dos a cero thing is cringe, and even if you don't, you probably hate the USMNT because that is how you are supposed to feel towards a rival.

Mexico is obviously the main rival here, and the U.S. has pretty soundly whooped that ass over the past 18 months. Canada looms as a future foil as they grow into themselves as a soccer nation. Outside of CONCACAF, England and the U.S. will always have a certain animosity because each sees in the other all the worst qualities of themselves that they refuse to recognize. Oh, the English? They're a sclerotic empire, clinging desperately to "glory" days that will never return, bitterly attached to a way of life that's gone, an American fan might think, blissfully unaware that sometimes the light at the end of the tunnel is a train. The Americans take themselves so seriously and have no perspective or interest in the rest of the world, a Brit, whose country is no longer in the EU and who thinks Jordan Pickford is a world-class keeper, might think. They're both right, in more directions than they would like to be, and the U.S.-England rivalry is fantastic because it's suffused with anxiety.

Also, the last time out, the U.S. squeaked away with a hilarious draw, and will really want to beat them on Black Friday. A side plot here is that Yunus Musah was supposed to be one of the best players in Arsenal's and England's youth setups, yet he spurned the former for Valencia, which led to him spurning the latter. I hope he scores three goals.

Most Likely To Go David Ospina Or James Rodríguez Mode

Who is the USMNT's best candidate for a breakout performance that earns them a career-changing transfer? Might this potential post-tournament transfer go well, like when Colombia's James Rodríguez went to Real Madrid after starring in the 2014 World Cup? Or could it go poorly, like when Colombia's David Ospina went to Arsenal after starring in the 2014 World Cup?

As the USMNT is one of the youngest teams in the World Cup, they are stocked with guys who are roughly in the prime age range to get Rodríguez'd/Ospina'd. Many of them are already rumored to be coveted by huge clubs, and a few of them already play for Champions League-level teams. The number one guy here is Gio Reyna.

Reyna is maybe the team's best player, and while everyone has known his deal for years as he's distinguished himself as one of the best prospects to emerge from one of the best talent incubators in Europe, he has yet to put together a full season's worth of the top-tier soccer he is clearly capable of. Many teams have been rumored to be making doe eyes at Reyna, and he's not going to stay at Dortmund until the next World Cup no matter what, though a good performance in Qatar probably accelerates his timeline and raises the prestige of the club that eventually buys him.

Other candidates include: Weston McKennie (rumors attach him to both North London clubs, which I'd say would each be a prime situation for an Ospinazo), Antonee Robinson (same deal but with Manchester City), and Yunus Musah (a prime Rodríguez candidate; who doesn't want this guy???).

Fun Geographical Fact

Which United State is closest to Africa?

. . .

It's Maine!

Good Flag Or Bad Flag?

From a purely vexillological perspective, I must begrudgingly admit that the United States has a pretty sick flag. Red, white, and blue is probably the single most iconic tripartite combination, and instead of horizontal stripes (Russia, the Netherlands), vertical stripes (France), or Texas (Chile, Texas), the U.S. flag is reasonably distinct, and the white stars on the field of blue always look cool. If only they could convert on this advantage and make some cool uniforms.

Good Anthem Or Bad Anthem?

Oooh say, can you see?

That this anthem sucks ass

Notable Moment In World Cup History

It is 2014. I am sitting in the foul-smelling apartment I'm renting with my brother and a bunch of friends the summer after graduating college. I am working a copywriting job in Downtown Oakland, and I have just sold my first few stories to Deadspin. It has been five years since I got into the United States men's national team, five years since they beat Spain at the 2009 Confederations Cup run, four years since Landon Donovan's goal against Algeria, and five months since future Bayern Munich superstar Julian Green picked the U.S. over Germany. I have locked in for the 2014 World Cup. I have harrowingly precise opinions about Brads Davis and Evans. After Portugal score an equalizing goal in the 95th minute of their group stage game with the USMNT, my partner is aghast at my despair. I have to go take a walk for an hour. I am invested.

I've spent the first 92 minutes of the team's round-of-16 game against Belgium palpitating, seeing little hope, yet investing too much of my heart into the U.S. hopefully triumphing. Tim Howard is doing stuff. The ball bounces to Chris Wondolowski. All that stands between the United States and the quarterfinal, is, well, nothing. That's kind of the whole thing: Thibaut Courtois is flapping towards the action, yet he's barely there. This is a hinge point. On the other side lies either failure—expected, bitter, harder-edged for enduring as, still, the most recent World Cup game for the USMNT—or a new frontier for United States soccer history—boldly stepping from the post-Landon Donovan era into something new. Isn't there real beauty in so much hanging in the balance for ephemeral moments at a time? Don't the high stakes of a World Cup afford it some kind of transcendence? Astride a fault line in history, the ball bounces onto Chris Wondolowski's right foot.

Wondolowski sends the ball into low Earth orbit. The U.S. loses.

How Can They Win The World Cup?

The United States can win the World Cup under the following conditions: England melts down into a stew of recrimination after losing to Iran, causing them to lose to the U.S. 3–0 (Musah 11', Reyna 68', Pulisic 71'); Qatar throws their weight around as the host nation (literally tilting the pitch towards their opponents' goals) and finishes second in their group, setting up a date with the U.S. in the knockout rounds, only to be forced to play on level ground after Joe Biden points to a chart with the words PLANES, MONEY, and OIL on it; by the quarterfinal, France's players have been in such an alarming state of proximity to each other that they start actively playing for the U.S. to make a point about how the federation needs to hire a manager who has more affairs, leading the Yanks to an unprecedented 171–1 (Aaron Long, OG 1') victory; somehow Canada wins Group F and makes it to the semifinal, where the heat gets to them and their defenders are seen sitting down and resting while the offense has possession, letting the U.S. win 3–2 (Aaronson 33', 42', 61'; Aaron Long OG 1', 2'); in the final, the U.S. draws Brazil. Overcome by the failures of Jair Bolsonaro to do Brazilian January 6, Neymar is benched, and the U.S. wins.