The fact that Autostraddle has lasted for over 14 years is a medium-sized miracle. Founded by Riese Bernard and Alexandra Vega as an outgrowth of the online fandom around the TV show The L Word, the website has stayed independent, stuck around through the increasing homogenization of the internet, and become, for lesbians and plenty of other queer people, the definitive website for our particular view of the world. Autostraddle is the kind of place that constantly surprises you with the breadth of its talented writers’ work without ever feeling like it’s carelessly throwing junk into the content machine to juice its traffic. It’s where you can read a long and intense history of Janelle Monáe and Tessa Thompson’s relationship; an exploration of queer cheerleaders in TV and film; friendly advice on dating; personal essays about COVID, Buddhism, race, relationships, and strap-ons; interviews with community members you wouldn’t see anywhere else; and a quiz that tells you what gay Bruce Springsteen song you are.

"I still don’t know of other sites that are really full of collective cultural knowledge specifically on queer people who are not cis men," said Kamala Puligandla, a former editor-in-chief.

With Bernard still in charge as CEO and CFO, Autostraddle has lasted beyond the shuttering of Bitch, the end of The Hairpin and The Toast, the sunset of Feministing, the far-right pivot of AfterEllen, and the decimation of a once-vital Jezebel. There aren’t a lot of sites like this left, for the gays or even for straight women. The ones that are still technically alive feel like they’re scraping by on brand recognition. But Autostraddle in early 2023 felt more vital and wide-reaching in its scope than ever before. Its continued presence as a publisher of smart, funny, and intimate queer writing made it a flower in a publishing landscape otherwise scorched by the twin fires of social media and SEO optimization.

But miracles can be messy. Like basically every other website, especially the independent ones, Autostraddle has struggled financially to stay afloat. And while corporate media possesses the strength to steamroll over the contradictions of growth and red ink, indie sites without rich benefactors can only briefly sustain even minimal losses before failing. Autostraddle has continued publishing posts to this day. But in May, the sudden and poorly communicated elimination of three critical contractors—subject editors Shelli Nicole, Ro White, and Vanessa Friedman—shook the site and its community to their core, threatening Autostraddle’s very existence. In the aftermath, a large number of contracted writers decided not to produce further work for the site; the director of operations went on unpaid leave; and after weeks of pressure, both public and private, Bernard sent a statement to the staff in mid-June saying she would soon no longer be CEO, either because she’s sold the site, or shut it down.

In addition to two past full-timers who provided historical context, Defector has spoken with eight current or extremely recent Autostraddle contractors for this story, most of whom asked for and were granted anonymity because the Autostraddle employee handbook explicitly forbids sharing internal discussions with anyone outside of the site. These contractors uniformly described a failure of leadership by Bernard, as well as frustration with her handling of the cuts in May and her lack of clarity around the site’s finances. Most of all, with the entire future of the site up in the air, they worried about what would happen to the underpaid contractors who had found a home for their work in this increasingly rare space.

Two weeks before publication, Defector reached out to Bernard, who said she was unable to do an interview by phone but could answer questions by email. After spending a week with the questions I sent her, she decided not to comment on most of them.

What follows is by no means the definitive history of Autostraddle. The site affected many more people, for better and worse, than could comfortably be covered here. But it’s a step toward understanding why a prominent force in independent queer media is teetering over the abyss.

Autostraddle was much more insular in its early days—Bernard and Vega were dating when it was founded, and it was built from the love of one TV show—but at least within its niche, it had buzz from almost the very beginning. In 2011, a writer for Rookie (also defunct now) called it “the best lesbian blog on the Internet,” adding that it was “at once lighthearted, thoughtful, and critical in addressing topics that range from economics to Pretty Little Liars to body image.” In 2014, it was notable enough for The Baffler (still kicking) to take aim at its self-consciously cutesy tone that reflected much of the internet at that time. “Cosmo for queers,” the headline called it. A year later, Vice (recently bankrupt) called Autostraddle “The Internet's Most Popular Lesbian Blog” in a lengthy feature that laid out much of the site’s early history and structure. At the time, according to Vice, the site paid contributors between $25 and $100 per post. It had 1,300 Autostraddle-Plus (or A+) members paying between $5 and $25 a month for extra stuff. And the year before, it had charged $595 per person for five nights at “A-Camp,” a gathering out west that was part vintage summer camp, part social justice conference, part life-changing week.

"Being surrounded by like 300 other queer people, it was like the best experience of my life," one contractor told me. "I had never experienced anything like it."

A-Camp had 11 incarnations from April 2012 to June 2019. For many in the Autostraddle community—readers, contributors, and future contributors—it was an all-too-rare opportunity for a week of fun as part of a gigantic group of other gay women. But other attendees, specifically from marginalized groups, had more difficult and hostile experiences. A post on Medium in July 2019 detailed many accounts of POC and trans attendees feeling othered and disrespected by white, cis campers and those in leadership roles. (The camp’s power structure was distinct from that of the site but featured some overlap, like Bernard on senior staff.) In response, Bernard announced in December of 2019 that A-Camp would be put on hold for 2020 with an eye on a reboot with POC leadership. It hasn’t returned since.

In response to the A-Camp controversy, which fed Autostraddle's reputation as being by and for a specific clique of white lesbians, the site put visible effort into diversifying its editorial staff. When current editor-in-chief Carmen Phillips lost the “interim” tag on her role in June 2021, a post from Bernard announcing the news said, “We have broken through our recent goal of publishing 50% of our posts by writers of color and making it explicit that being a home for lesbian and queer communities also means being a home for trans people of all genders.” Still, Bernard’s presence at the top of the site through the A-Camp reckoning kept Autostraddle inextricably tied to the entirety of its past. And for those who have been around Autostraddle long enough, the lack of real closure or the arrival of a better A-Camp foreshadowed the ignorance and confusion that have defined these last few months.

"The problems that are weighing on Autostraddle now are the same problems that were weighing on Autostraddle all along," one contractor said, "which are the blind spots of privileged cis white leadership."

The more recent trouble began in March, with the launch of the latest Autostraddle fundraiser, the first since quickly meeting its fundraising goal of $145,000 last fall. While past fundraisers at the site were marked by a kind of let’s-put-on-a-show queer community camaraderie, this March edition furthered a trend from the last one with messaging that was intense, desperate, and signaled that Autostraddle had limited time left to live. Fundraising director Nico Hall’s post “We Need You To Buy Us Some Time Before Time Runs Out” set off alarm bells both in and outside the company. “I’ve never felt more at the end of my rope in this role or as uncertain of our future as I am right now. I’ve also never felt the extent of this gnawing guilt and anxiety that has made writing this post, draft after draft, harder than it’s ever been,” Hall wrote. “We need to raise $175,000 by March 29th, or we’ll be gone before Pride,” they added in bold. Readers and writers alike were extremely worried for the future, but like previous fundraisers, this one, too, was a quick success, implying to the community that disaster had been averted.

In April, largely as a result of concerns about the fundraiser’s messaging, Autostraddle’s three subject editors had a meeting with Bernard, Phillips, and director of operations Laneia Jones to discuss their concerns. (Jones, whose LinkedIn lists her experience with Autostraddle as dating back to March 2009, acted as the site’s human resources department, per the employee handbook.) The subject editors had a unique role in the company in that they weren’t full-time staff but had significant influence over the day-to-day experience of reading the site. Each of them had a particular beat—community for Friedman, culture for Nicole, and sex and dating for White—and got a $400 monthly budget to commission articles under that category. But in the context of the fundraiser, they had no more insight into the company’s financials than any reader or contributor. After Hall’s worrying posts, they sought clarity and confirmation that their jobs were not in immediate danger.

At the meeting, the subject editors were told that, while the macroeconomics of independent digital media weren’t exactly luxurious, they could relax about their jobs for the time being.

"We left the meeting feeling like, OK, mom and dad said ‘We’ve got money issues, but you’re good,'" Nicole told me.

Three weeks later, on May 10, the subject editors received—without warning—a Slack DM from Jones, informing them that their positions would be eliminated in three months’ time, and that afterward they would have the option to stay at Autostraddle for $500 a month while doing a fraction of their previous work. When Friedman, Nicole, and White made this news public a few weeks later, the community that supported Autostraddle was shocked and furious. How could a website that had so recently begged for money and received it turn around and cut key positions? Without any real financial transparency, writers and readers couldn’t figure it out.

Though it does fundraising, Autostraddle is not a non-profit. This means the way Autostraddle talks about its finances can be annoyingly opaque and coy—gesturing at the idea of transparency while still forcing an outsider to work out the pieces of a puzzle.

"Part of what’s confusing for a lot of folks, myself included, about what’s happening right now at Autostraddle is that, in many ways, there has always been a commitment to public transparency," said Rachel Kincaid, who rose from unpaid intern to managing editor at Autostraddle before leaving in 2021. "There was always a lot of numbers available, but it’s in a way that I think I still never really felt clear on the holistic financial picture."

“A lot of it was very much Riese’s own personal way of managing finances, that were certainly not particularly clear to anybody else,” Puligandla said. “We did talk about the budget together, but there were certain parts of it that were not totally clear to me, like where they’re going to, where they’re coming from, and how Riese expected different things to happen.”

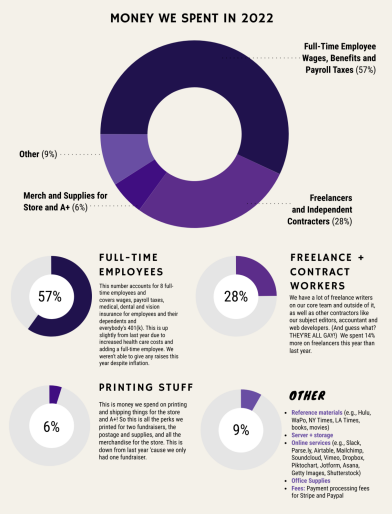

This opacity is most evident in the “By The Numbers” annual report available to A+ subscribers, which presents different pieces of spending and revenue not as dollar figures but as percentages in a pie chart, like so:

And these reports don't give much explanation for why certain decisions were made, even if it gives numbers, like in this flippant paragraph written by the CEO/CFO, from the 2022 report:

Some big wins this year: We made huge gains in advertising in 2022 thanks to our new Brand Partnerships Director Anya Richkind and our partnership with Q Digital — a 238% increase from 2021! We had an incredibly successful and very fast fundraiser in 2021! (Sic: I think this means 2022.) Unfortunately, we also spent $200k more than we earned in 2022 — even after the fundraiser — which’s approximately the size of that loan. As one might say: yikes!

Some basic algebra can add at least some specifics to the budget. In the 2022 report, Bernard mentioned taking out a Small Business Administration (SBA) loan for $199,000, which then accounted for 15 percent of revenue. That number implied overall revenue of approximately $1.3 million, broken down like this:

- A+ Members: $637,000

- Advertising: $273,000

- Loan: $199,000

- Donations: $170,000

- Merchandise: $65,000

- Affiliate Links: $26,000

Meanwhile, this post from March 2023 referenced a budget of $110,000 per month, which also worked out to approximately $1.3 million, cut like this:

- Full-time Employees: $741,000

- Freelance + Contract Workers: $364,000

- “Other” (Site upkeep, payment processing fees, etc.): $117,000

- Printing and Shipping: $78,000

Defector viewed By The Numbers posts dating back to 2018. The critical change in the site’s financials in that time has been the loss of A-Camp, which accounted for 39.4 percent of overall revenue in 2018 and 28 percent the following year. Advertising, too, continues to be a trouble spot for media generally, and particularly for a site so unabashedly about gay women.

"A lot of our advertisers were in sexuality and sexual wellness spaces, a lot of sex toy companies, some queer porn," Kincaid said. "Which, to be clear, I loved working with those companies. It just was sometimes frustrating that it felt like those were the only clients … When somebody looks at your content and what they’re seeing is a dozen different sponsored articles about different kinds of dildos and what they want to sell is, like, a home seltzer machine, I think they make a different choice."

Bernard told me that, for most of Autostraddle’s existence, its spending was determined by how much money it made, not how much it hoped to make. That point is backed up Kincaid, who said that layoffs due to budget cuts were nonexistent in her decade-plus at the site. But during a moment of optimism in 2019, Bernard said, "The senior team decided that we shift our focus: Instead of determining our budget based on what we earned, we’d decide what we needed our budget to be and figure out how to earn it, even if that meant more fundraisers."

Not long after this shift in approach, the site’s situation was a precarious one. In 2020 and 2021, without A-Camp and amid the difficulties of COVID-19, Autostraddle leaned on a pair of PPP loans, which could be forgiven. Per Bernard's 2022 By The Numbers, Autostraddle then took out an EIDL loan from the SBA, which must be repaid. A+ memberships (which have a variety of tiers but number overall at a claimed 6,900) along with donations now amount to the clear majority of the site's revenue, which makes Autostraddle’s regular fundraising drives a wobbly but necessary pillar of the business—even though, Bernard noted, they get more difficult the more you do them.

If they hadn’t met their goal in March, Bernard told me that Autostraddle had been in legitimate danger of closing by Pride. "We raised around $200k in the fundraiser and had $230k in the bank on June 1st. And we had $195k left on our SBA loan to pay off," she wrote.

"It seems like they’ve run it for so long in this Rube Goldberg machine and paperclips way," a contractor said. "It’s worked, somehow, but at some point you have to start trying to move toward something more sustainable that burns fewer people out. And it didn’t seem like that was being addressed at all."

"While I was there (in 2020), I was like, 'I could imagine a way this could be profitable,'" Puligandla said. "Were those things a high priority? I don’t think so. I don’t know that they’re particularly the most business savvy, and it was at this turning point where it needed to become business savvy to pay people the amounts of money that are worth the kinds of changes they wanted to make.

"Was there someone who was there to be like, 'Oh, this is what a business plan looks like'? No."

An ongoing tension in the site’s "Rube Goldberg" structure is the divide between full-time staffers and contract workers. A full-time job at Autostraddle, which covers three editors and three people on the business side, plus Bernard, pays between $55,300 and $85,000, per a June email from Bernard to A+ members. According to the 2022 report, those salaries come with medical, dental, and vision insurance for employees and their dependents, plus a 401(k) program. (When Defector reached out to five of Autostraddle’s six current full-time employees, three did not respond, while two directed my questions toward Bernard.)

While that’s a solid gig by independent media standards, the contractors are not so flush. The subject-editor tier of workers, whose elimination sparked the site's present difficulties, received a base rate of $2,000 per month for a stated 20 hours per week that, one editor said, often was much more. Contractors, meanwhile, received below-market rates. The highest per-piece payment I heard from anyone I talked to was $300 for certain personal essays, and typically closer to half that. An early 2022 call for writers from Autostraddle lists the rates as between $80 and $200, with "our most common rate" being $80 to $120 for less than 1,000 words. (I was told by several contractors that the floor has since been raised to $100.) While Autostraddle said it had been adding more writers of color, it wasn’t lost on contractors that the living wages enjoyed by white full-timers (specifically on the business side) were paid for by the exploitation of Black, trans, and other marginalized contributors.

"They had embedded in us, 'We are an indie company, we never are gonna have a lot of money, but you’re writing for a marginalized audience that truly digs you, and you’re helping them be seen,'" said Nicole, a writer before she was a subject editor. "It was that kind of vibe that made me feel like, 'Oh, I’m supposed to be getting paid 80 bucks to write a piece that takes me a very long time to write and edit.'"

While the site’s strides toward diversity grew Autostraddle beyond its more cloistered early audience, and some contractors described extremely positive experiences with the readers and commenters outside of the typical random trolls, others felt keenly aware of its history as a near exclusively cis, white space with some readers who seemed frustrated that trans women and women of color had a new platform.

"It was the easiest place for me to write as a trans person, and I never had to explain myself, like I've had to in other spots," said Niko Stratis, a now-former contractor. "But there weren’t a lot of trans people in positions of power or leadership. There definitely were no trans women with any power or leadership at all. And on a queer-focused website, where a lot of the comments were denigrating trans women specifically, it would have been nice if at least one of us had any sort of power there at all." (Bernard gave no comment to my questions about whether Autostraddle had a problem with transphobic commenters, or if it was a weakness that the site had no trans women in leadership roles.)

Nicole, too, described a double standard with white leadership—that they could be rude to her, but not vice versa—that ultimately led to her feeling tokenized. (Bernard gave no comment when I asked her about this.) She also noticed, as she attempted to build up the site’s Black readership as a subject editor, when pieces she commissioned from Black writers brought in minuscule traffic and engagement compared to posts by white writers on the same day, which underscored both the difficulty and the potential payoff of expanding the site’s scope.

"I wasn’t going to stop using these writers and making this content just because the white folks who were used to coming to Autostraddle for years were so used to not seeing it," she said.

Bernard tried to smooth over the concerns of the site’s community with a post on May 23, the day after the subject editors went public with the news that their roles were ending. She noted that, despite what those donating might have believed, Autostraddle didn’t go back on any explicit promises by getting rid of the subject editors. "During our last fundraiser, we asked you, our readers and funders, to buy us some time to figure out a way forward," she wrote. “In the past we made other promises—new hires, improvements—and in the past, we promised we would avoid cuts. We didn’t make that promise during this year’s fundraiser because by the time we got there, I already knew cuts were possibly on the horizon."

Bernard blamed the need to pay back the SBA loan and the decline in advertising for the necessity of the cuts. (In her A+ email from June, she elaborated that ad revenue has fallen 77 percent from last year.) She advanced the message that the fundraiser stopped Autostraddle from dying but didn’t prevent it from shrinking. "We’re drawing in our defenses and doing our best to fortify what we have left," she wrote.

The site’s writers nevertheless remained confused and upset. That Bernard, who is white and made the call to eliminate the subject editors, had more say over the direction of editorial than Phillips, who is Black and has the title of EIC, seemed to undermine the site’s larger post-A-Camp re-envisioning.

Bernard gave no comment when I asked about this interpretation of her power. Phillips declined to be interviewed for this piece and directed me toward Bernard. But Puligandla’s experience working with Bernard in her CEO/CFO capacity after she stepped down as EIC in June 2020 illuminates the failure of Autostraddle to clearly define the limits of its leader’s duties. While Bernard portrayed the change at the time as a necessary passing of the torch, especially in the midst of nationwide protests against racism, Puligandla said that she continued to exert editorial control from above.

"I think that she was really afraid of being called out again after the whole A-Camp thing," she said. "And I think she just felt like it would be easier for her if I were in charge, and then, like, no one would come for us.

"I ended up leaving because it felt very clear to me that it didn’t matter what my title was—Riese was in charge … I did feel like there was not a lot of power attached to my position."

The end of Nicole’s tenure as subject editor was met with particular alarm, as a space that had at least superficially aimed to elevate Black voices in recent years suddenly and unceremoniously lost one of the crucial people who had helped those voices in.

"I think the people who made the decision to fire the subject editors were really taken off-guard by the fact that that decision had significance beyond firing one person," one contractor said. "And I don’t think they had given much thought to what it meant to fire the Black pop culture editor, and what that would mean for the Black readers who came because of that editor’s work, and the Black writers who were submitting because of that editor's work. I don’t think they understood that there is a specific inter-community goodwill that those editors represented and cultivated. And because they didn’t know that, they weren’t prepared for what happened when they lost that goodwill.”

Said another contractor, "If I was in charge, I would’ve probably shut the site down before laying off Shelli, because she’d done so much to shape the culture of the site for the better … To let someone go who, along with Carmen, did so much to make the space less white shows a real failure of leadership and failure of priorities."

Bernard, in her message to readers, wrote: "Shelli is a treasure. She’s a star. Nobody with the money in the bank to keep her in that role would ever not do so." I mentioned this line to her and asked, “As long as some people at Autostraddle were continuing to be paid, why cut Shelli specifically?” She gave no comment.

Said Nicole: “Imagine how stupid I feel I look to Black and brown people who I told could trust coming to the site, that could trust this space was good for them.”

Even a great leader would have trouble maintaining morale in the face of such disappointing news, but the actions of both Bernard and Jones, the operations director, in the aftermath of the cuts only added fuel to the fire. Jones’s behavior turned combative and erratic, with consequences that resonated across the entire site. When the subject editors informed her that they wouldn’t take the new $500/month deal, her tone became, Nicole said, “increasingly rude and reckless” in their conversation, as she was apparently frustrated by the idea that she’d be seen as a villain due to a difficult business decision. An Autostraddle newsletter Jones wrote in May after the subject editors were told the news signed off with the line "I hope you have the least petty, most normal weekend you’ve ever lived through in your entire life!" which writers saw as unprofessional and disrespectful. (Bernard acknowledged this later in an internal note to staff but said a public apology would be "legally inadvisable.")

And on May 26, as everyone still tried to sort through the rubble, the subject editors also found themselves unexpectedly locked out of key programs needed to finish off their work, while some contributors realized that editing privileges they made use of to streamline the site’s workflow were no longer available.

Slack messages from Phillips viewed by Defector said that none of the site’s senior staff members, aside from Jones, were aware of the change until it was brought to them. Jones later apologized via text to Nicole and Friedman for what she called a mistake, but three people who spoke with Defector as well as internal communication shared with Defector indicated the scope of the lockouts required multiple steps, and cast doubt that such a measure could be taken on accident. Furthermore, Jones seemed to be leaving the public-facing internet entirely. Her Instagram is private, and the Twitter formerly linked in her Autostraddle profile has been deleted within the past two months. On May 30, Defector witnessed, all of the posts she’d authored disappeared from Autostraddle, only to return the following day.

"When I was seeing stuff happen that I knew Laneia was in charge of, I was just like, 'What the fuck is going on here?'" Stratis said.

"It started to become sinister," Nicole said, "And it started to feel very retaliatory."

Defector emailed Jones multiple times at both her personal and professional addresses and got no response. When I asked Bernard for Jones’s phone number, to ensure she had an opportunity to answer questions before the piece ran, Bernard responded, "Laneia's aware that the article is happening!"

Jones was initially placed on paid leave after these issues were discovered. In a meeting on May 31, three contractors told me, writers voiced their concern about the light consequences for this behavior: It touched a nerve that Jones would be getting paid, more than these contractors had ever made, to not do her job in a period when Autostraddle was making gut-wrenching budget cuts. In response, Bernard agreed to make Jones’s leave unpaid, and in an internal note to staff, she wrote, “We will work with an outside HR professional for any HR issues going forward.”

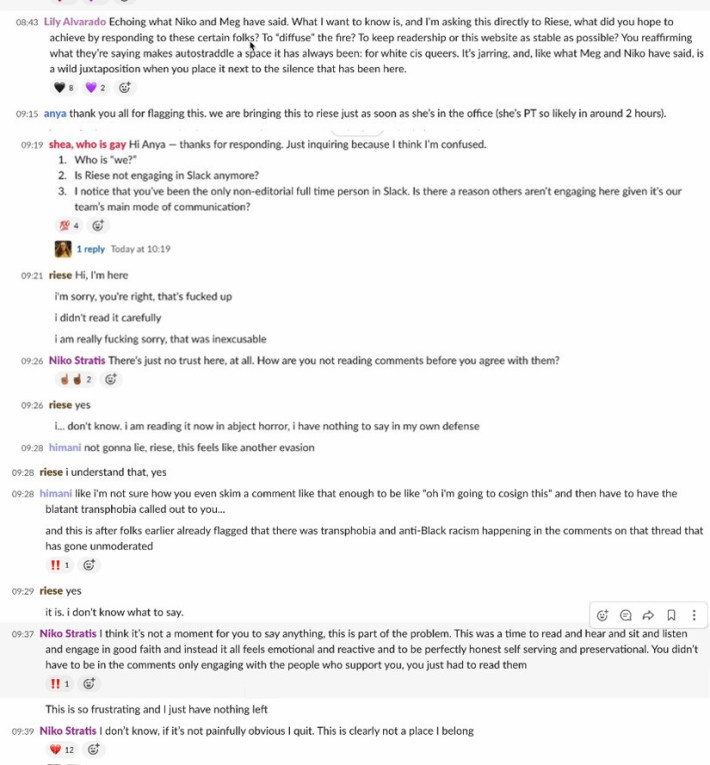

While the director of operations was especially unhelpful at answering questions or assuaging concerns, the CEO/CFO scarcely did any better. After Bernard's excuse-heavy post hit the site, writers remained incensed that, while they themselves struggled to get ahold of her to figure out concrete steps moving forward, she remained in the comments responding to views sympathetic to her own. One comment in particular, which seemed to take aim at the ways the site had become more Black and more trans since its early days, earned a "thank you" reply from Bernard the night of May 30 and a disavowal of that reply the following morning when a staffer brought it up in Slack. This moment in time from that morning, in an Autostraddle Slack channel with dozens of members, provides a snapshot into the complete lack of direction provided by the company’s leadership.

"She tries to make herself a victim in these situations by starting to cry, and it’s like weaponized incompetence," Nicole said.

In response to Defector's request for comment, Bernard wrote: "I’ve never wanted to be CEO of anything! But keeping me in that role enabled us to save money, because normally CEO/CFOs expect larger salaries than mine and ‘cause I write a lot of our high-traffic content." (In a lightly revised set of answers sent the following day, the exclamation point was replaced with a comma.)

A statement from a coalition of Autostraddle writers, who ended up in a Discord together after being particularly vocal about their frustration in Slack, laid bare to the public the site’s many flaws. They questioned whether Bernard’s cuts undermined the power of Phillips, the EIC. They wondered openly whether the power of the white non-editorial staff dwarfed that of POC editors in leadership positions. Ahead of a site-wide meeting, they asked for a separate human resources contact, detailed financial reports, and a plan for the site to center Black and trans communities.

"The stated commitments to transparency and equity are not coming through in actual, material ways. That needs to change," the group wrote.

The Zoom meeting on May 31 was scheduled for two hours, lasted for three-and-a-half, and further soured the mood. Per contractors present, Bernard came completely unprepared to address the future, reflexively apologizing when confronted with her writers’ grievances but unable to take real responsibility for any of them.

"So much of the meeting was us basically repeating back to Riese her own patterns of behavior and her own actions. And then she would hear her own actions said back to her, and she would be like, 'Yeah, that's bad,' or 'That shouldn't have happened.' She was figuring out what needed to change, but there was a lot of what and not a lot of how," a contractor said.

"It’s very frustrating to watch, and to continually feel let down by somebody," Stratis said. "And for someone to just repeatedly have no answer, or plan, or idea of what she’s going to do. Just a lot of saying 'I’m sorry,' and 'I need more time,' which is basically like saying nothing at all."

"My impression of Riese during the Town Hall meeting was of someone who believed that if they sat there for two hours and engaged minimally within the meeting, that it would blow over within a week," wrote A. Tony Jerome, a former Autostraddle contractor, in an email exchange with Defector. "The precedence was still given to cis white queer people in this space, and there was a moment when I was talking about how Autostraddle made me hate writing/not want to write anymore, that I could really feel like nothing about what I was saying, who I am, or how important this is to me permeated her at all. It felt like I was yelling into a void, and though I’m glad I said my piece, I wish it had been said to someone who cared."

The consequences of Bernard’s inaction was a greater burden placed on the site’s POC editors, who were left to deal with the fallout of all this uncertainty.

"Editors who I hold in the highest imaginable esteem were breaking down crying on camera because they were hearing that the multiply marginalized writers who they personally had recruited to write for the site had never felt safe or welcome," a contractor said.

Amid these difficulties, the publication schedule of the site essentially screeched to a halt, and it’s still struggling to recover from both explicit departures and quiet quits. In a paywalled curated staff chat with A+ members on June 28, Phillips said that in addition to the three subject editors, nine writers "have decided that their time at Autostraddle has come to an end," while "a smaller group of writers" haven’t made a choice yet in either direction. As a result, senior staff including Bernard have taken on a larger share of the day-to-day writing duties. Their contributors had written for little money because they believed in the site and its mission, but with that belief irreparably shaken, there was nothing left to stay for.

"I’m embarrassed to be one of the people who left in 2019, believed there was a substantial amount of change done and re-applied to come back in 2022," Jerome wrote. "I wanted things to be better, and it’s time I stop putting my faith into something that has not proven worthy of that trust."

"It’s really devastating to watch people who you love be disillusioned right before your eyes," a contractor said.

It’s clear to everyone that Bernard is all but done at Autostraddle. While the site is, in some ways, her life’s work, she was consistently described to me as burned out and absolutely exhausted by the compounding difficulties of running this company. One contractor described her to me as "living in a blast bunker. She’s kept us alive for so long, but she’s just kind of assumed a crash position."

"Autostraddle is something (Riese) built from, like, a room to what it is now," Nicole said. "So I understand wanting to keep it safe. But at the same time, you have to evolve and grow. And if you’re not willing to do that, then you should have left a long time ago.

"I’m sure she is exhausted. I would be exhausted too if a whole bunch of my Black and brown and trans writers left."

In that June email to A+ members, Bernard wrote, "What is overwhelmingly clear to me is that Autostraddle’s next chapter requires a new CEO with a fresh perspective on how to structure and grow this community, and I’m actively working towards making that happen as soon as possible." In her internal note to staffers, she stated that even more drastic changes to the site were coming—potentially its end. "I will have a definitive sell or shutdown path determined by the end of July at the latest," she wrote. None of the writers I’d talked to said they’d even heard a rumor of who might currently be interested in a purchase.

There was chatter in May about the adrift Autostraddle writers "doing a Defector"—starting a new independent site, this time worker-owned—but that project remains hypothetical today. The future of these writers, instead, feels lonelier. Nicole is writing on Substack. So is Stratis. So even is Heather Hogan, who’s still employed full-time as a senior editor but recently turned on subscriptions for her own newsletter. Their writing still has a place to exist. But if other writers follow suit and leave Autostraddle either a husk or museum of its old self, something meaningful will have been lost. Even with all of its problems, Autostraddle was an honest-to-god coherent website where queer people gathered to share a piece of themselves and see the world through each other’s eyes. Though it clearly fell short of its goals, it attempted in its ideals to welcome all corners of the queer community and shut out those who wouldn’t do the same. Substack isn’t that. Twitter isn’t that. Without Autostraddle there will continue to be a lot of queer writers in precarious positions, only this time they won’t be in each other’s eyeline.

"The remaining writing staff is still largely POC and trans, along with other intersecting marginalized identities," one contractor said. "If Autostraddle folds tomorrow, those people are out of jobs."

The contractor added, however, "I hope whatever happens happens quickly, because this current limbo is impossible and sad."

Kincaid noted, too, that the difficulties Autostraddle had in finding advertisers outside the queer community could affect the writers trying to get work at more mainstream places.

"When you’re applying to staff writer gigs or showing your portfolio to potential content writing clients, worst-case scenario, people are grossed out and it feels radioactive, and best-case scenario, honestly, they see it as very niche and very siloed. Like, 'That’s great, but I’m not looking for gay stuff.'

"It’s frustrating, because there are so many talented people there who have done such an incredible range of work. Especially with the industry and the job market what they are right now, I’m not sure what it would look like for anybody to try to get work or position themselves as a media worker outside this very narrow, identity-based niche."

That’s scary in itself, but for those who poured their hearts and souls into the site they could not ever own, there remains an additional regret. Regardless of her mistakes, it’s Bernard who retains full control of this place in its capacities as both a publisher and a symbol. For those who’ve left, their writing and their community still hold promise, but everything related to Autostraddle still requires Bernard’s approval. Even if that also means shouldering the financial responsibility, owning such a beloved place is no small thing.

"She’s gonna get another chance," Nicole said. "Even if she sells, she still wins, because she has all that money, and I am sitting on nothing from that site."

I asked Bernard if she agreed that she’d be the most financially and professionally secure of all those at Autostraddle after this chapter wrapped. She replied, without elaborating, “No.” The next day, she added, “I have no way of knowing this.”

This is not how miracles are supposed to end, awash in confusion and anger, with an uncertain and doubt-filed future. But miracles and the people who make them happen are two different things, and anyone who appreciated Autostraddle should hope the next chapter makes that clear. Just as the closing of a concert hall doesn't remove its musicians' ability to play, or the shuttering of a restaurant doesn't stop its chefs from knowing how to cook, the end of Autostraddle isn't the end of the writers who gave it meaning. There will still be queer writing on the internet for as long as there's an internet. And after it's gone, there will still be queer writers.