In 1954, Elgin Baylor left the largely black and wholly segregated metropolis of Washington, D.C., to play basketball at the College of Idaho, a small, almost all-white private institution located in the small, almost all-white town of Caldwell in the western part of the almost all-white state. The integrated team, led by the dominating freshman who'd eventually get credit for changing the way basketball was played, went on to have the best season in school history. Administrators at the college reacted to the good fortunes brought on by this amazing invader by blowing up the basketball program. And then Baylor was gone.

Baylor was already a legend back home on his side of town and would later become one of the greatest NBA players of all time with the Los Angeles Lakers. His short stopover at a school that didn't care about basketball and was located in a remote burg where no townies knew him or looked like him remains among the bizarrest quirks in hoops history So, how the hell did the greatest player ever born in D.C. and among the best ballers born anywhere find himself in Idaho?

“W.W. got me out there,” Baylor tells me.

That would be Warren “W.W.” Williams, a pal of Baylor’s since they were kids on the D.C. playgrounds, and a teammate on the meteoric C of I squad. I’d called Baylor, who turned 86 years old this month, to talk about his old friend, who died in late spring at 85 years old. According to Williams’s family, the cause of death was COVID-19.

After his death, surviving loved ones recalled Williams’s full life, and the large presence he’d had in D.C. for more than half a century. He was a schoolboy superstar in multiple sports, a guy who helped run an illicit but popular neighborhood numbers racket as a kid, and later got D.C.’s legal lottery launched as a grownup. He was a military veteran, restaurateur, philanthropist, and club owner who was close enough to former Mayor for Life Marion Barry and other local power people that for a time he was allowed to run a go-go out of the city government’s downtown headquarters. (That didn’t end so well.)

For sports fans, however, nothing in Williams’s legacy is cooler or more significant than his close relationship with Baylor and the impact their alliance had on basketball history. Some 65 years ago, that friendship got them out of D.C. during an era when it was gripped by racial segregation and social upheaval, and brought them some 2,400 miles west of the nation’s capital, to the proverbial middle of nowhere. Baylor, known as the inventor of “hang time” for being the first guy to play the game above the rim, was responsible for getting the outside world to recognize his hometown as a basketball capital. But he had to leave for that to happen—and Williams was the guy who got him out of town.

Williams wasn't Baylor's athletic equal in high school, nobody was, but he was no slouch on the playing fields: He’d been named to all-city teams in football and basketball at Dunbar High School even before his senior year. Baylor, meanwhile, was already a hoops legend in the city’s black community while starring at crosstown rival Spingarn High School.

In a more equitable world, high school athletes as talented as them would have had plenty of college options. But by then they’d learned the hard way that the real world was not fair. Throughout Williams’s and Baylor’s entire childhoods, the best public playgrounds and swimming pools in the nation’s capital were reserved for whites. In a 1999 interview, Baylor told me about having to walk past a nice rec center near his home, located just blocks from the U.S. Capitol Building, on his way to school every day, but not being allowed to use the pool, tennis courts, softball fields, or basketball court, because that was reserved for whites only.

“The police even put chain locks on the gates around the basketball court so we couldn’t get in when the park was closed,” Baylor said. “The older kids would sneak in at night over the fence and play with whatever light they could get, but most of the time, we just played stickball in the streets.”

In his 2018 autobiography, Hang Time, Baylor wrote that the nearest "black park" had only "a sandbox and a swing." That lack of facilities kept Baylor from starting to even play basketball until he was 15.

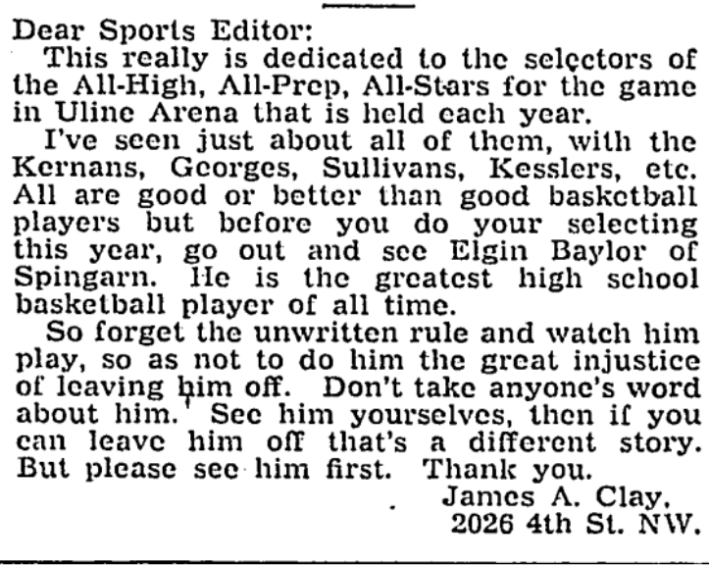

And like the playgrounds, all the public schools in their hometown had been segregated by race their whole lives to that point—Dunbar, like Spingarn, was all black. As a senior at Spingarn, Baylor broke all the city’s major scoring records, marks set a year earlier by Jim Wexler of all-white Western High School. Baylor’s 63 points against Phelps High in 1954, which topped a 52-point Wexler outing, is still the single-game boys record for D.C. high schools. Wexler had gotten tons of attention from the mainstream, or white, media, which mostly ignored Baylor. A letter to the editor in the Feb. 18, 1954 edition of the Washington Post from a reader named James A. Clay implored the paper to waive its “unwritten rule” that limited coverage of players from the city’s black schools and send sports reporters to “go out and see Elgin Baylor of Spingarn.”

“He is the greatest high school basketball player of all time,” Clay said.

To get word out about the underheralded wunderkind, benefactors including Sam Lacy, the legendary sports editor of the Afro-American, promoted several games at D.C. arenas pitting Baylor’s youth team, Stonewall A.C., against squads of white stars from local high schools and colleges in 1954, after his senior season. “The reports I got all said that [Baylor] was playing a different brand of basketball from other youngsters at the time,” Lacy told me in 1999, when he was 95 years old but still working as the Afro-American’s sports editor. “And the mission of the Afro was to get the word out about the black schools and kids like him.”

Opposing players in the contests, which were described in newspaper previews as “mixed basketball battle” and “interracial cage tourney,” included Wexler and Gene Shue, a future Hall of Famer who was then a senior at the University of Maryland just weeks away from being taken by the Philadelphia Warriors with the third overall pick in the 1954 NBA draft. Baylor outscored and by acclaim outplayed both.

“He showed me basketball at a totally different level—another world, heads and shoulders above anything I’d ever seen,” Wexler, who died in 2011, told me in 1999. “He reverse-dunked on me! You have to remember: Nobody did that before Elgin Baylor.”

"Elgin’s still in high school,” James “Sleepy” Harrison of Stonewall A.C. said in 2012, “but he put [Shue] in his hip pocket.”

The racial dynamic of D.C. and the whole country was changing in 1954 as Baylor and Williams were getting out of high school: A schoolmate of Baylor’s and member of the Spingarn basketball team named Spottswood Bolling was a lead plaintiff in the litigation that became known as Brown v. Board of Education, which initially legally challenged D.C.’s refusal to admit black students to the city’s white schools and ultimately challenged segregation in all U.S. public schools. On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court ruled in that case that D.C.’s system of separate and only allegedly equal schools was unconstitutional.

But the changes inspired by the Brown v. Board of Education ruling would come too late to change their high school experience—the Supreme Court's ruling came mere weeks before Baylor and Williams’s graduation from their all-black high schools. And systemic racism severely limited their college options. Baylor had already decided he was done going to segregated schools; he turned down Virginia Union, a historically black university in Richmond, Va., the only school that had offered both him and Williams scholarships. But most colleges in and around the nation’s capital were years away from even allowing black athletes to suit up. George Washington University didn’t allow non-white athletes until 1963. Maryland, whose best player Baylor had bested in those exhibition games, wouldn’t enroll its first black player until 1965. Even Georgetown, which by the 1970s under head coach John Thompson could rightfully boast about the blackness of its basketball program, didn’t integrate the team until 1966. (Thompson, a D.C. native who died last month at 78 years old, became the first African-American coach to win an NCAA championship in 1984. Thompson shared courts on the city's playgrounds with both Baylor and Williams as a kid.)

The police even put chain locks on the gates around the basketball court so we couldn’t get in when the park was closed.

Elgin Baylor

So the pals cast a wider net. A February 25, 1954 report in the Washington Post said both Baylor and Williams were being looked at by Indiana University, then the reigning NCAA basketball champs. Both Baylor and Williams told me over the years that the school never made an offer. The absence of any college commitment offers led to rumors that Baylor would be going straight to the NBA, an unheard of leap for a high school player at the time. The Post reported that same month that the Boston Celtics were hot for Baylor’s services. “If he isn’t going to college, we want him with the Celtics now,” said Ralph “Shag” Shaughnessy, identified by D.C.’s top newspaper as “chief scout for Red Auerbach’s Celtics.”

In a 2005 interview, Auerbach told me that he had indeed been in awe of Baylor during his Spingarn days, but said stories that the team pursued the schoolboy star were pure hokum. “At that time I was the [Celtics’] general manager, the coach, the chief scout, the guy who arranged travel things, the marketing guy, everything. So I’d know if that was going on,” said Auerbach, who despite being the Celtics guru lived in D.C. his whole adult life. “As great as Baylor turned out, I didn’t have any time for high school kids.” (In 1962, Reggie Harding of Eastern High School in Detroit became the first player to go straight from high school to the NBA when he was drafted in the fourth round by the hometown Detroit Pistons.)

With the summer after graduation almost over and still no takers, Williams got his first serious bite. A neighbor had a brother who played for the Harlem Globetrotters who told Williams that during the traveling troupe’s recent visit to Idaho he heard about a college in a small town that was looking for football players of any color. Soon enough, Williams was on a train out West.

In 2005, Williams told me that during that visit he met with Sam Vokes, the head coach on the C of I football team, and was quickly offered a gridiron scholarship. Williams wasn’t the first black player to play for Vokes. R.C. Owens gets credit for breaking the school’s athletic color line in 1952. Owens, a future star tight end for the San Francisco 49ers, Baltimore Colts, and New York Giants, is best remembered as the inventor of the “alley oop” pass and catch play in the NFL.

Vokes was also C of I's head basketball coach. When Williams found out that Owens played both sports for him, he asked if he’d be allowed to go out for hoops, too. Vokes said sure.

But Williams wasn't negotiating with the school just for himself. Turns out that before he got on the train for Idaho he'd already made a deal with Baylor to find a college where they could play together. Dick Hahn, then a member of C of I's basketball and tennis teams, said it was common knowledge among athletes at the small school (total enrollment: 500) that Williams and Baylor were shopped as a tandem. "I was told several times at the time that they'd pledged to each other that wherever Williams was given a scholarship, Baylor would attend the same school," said Hahn, adding there was wonderment among the student body that a superhuman like Baylor had dropped in their lap.

He reverse-dunked on me! You have to remember: Nobody did that before Elgin Baylor.

Jim Wexler

Williams through the years told his family about that same pledge. “My Dad always longed for a sibling,” said his son, Warren Williams Jr. “And he was probably never going to go anywhere without somebody he wasn’t close to. That was Elgin.”

So after landing himself the free ride to C of I, Williams talked up his buddy back home. In 2005, Williams recounted the sales pitch he made to Vokes about a half-century before about Baylor: “I’ve got a friend who’s the best basketball player in the country!” Williams told Vokes.

Vokes was out to get the best athletes on all his teams, racial concerns be damned. Roger Reynoldson, a white Idaho native who was a reserve on the 1954-1955 team and Owens' roommate, said that C of I athletes were “the first black people I’d ever had a single interaction with.”

“Caldwell was as white as could be, you know?” he said.

After hearing that Williams's basketball wizard friend was 6-foot-5 and well over 200 pounds, Vokes gave him the go-ahead to bring Baylor out West, too. With one qualification: Baylor would also play football. Williams knew Baylor had never played organized football before. But he called back to D.C. to persuade Baylor to join him across the country at a school he’d never heard of to play a game he’d never played.

“W.W. says, ‘Come out to Idaho!’” Baylor said of their August 1954 phone conversation. “So I say, ‘Where’s Idaho?’”

In our recent conversation after learning of Williams’s death, Baylor told me that apart from staying with relatives in Virginia or Maryland, “going to Idaho was really the first time I’d ever been anywhere outside D.C.” But Baylor, who'd been spending his summer playing ball with Stonewall A.C., had no better offers. He ignored any geographical or athletic misgivings and jumped on a train from Northeast D.C. to the Great Northwest.

Vokes saw immediately that Baylor really could live up to Williams’s hyperbolic-but-true basketball billing, so he excused him from having to suit up for football games. "We all tried to get him to play," recalls Ed "Buzz" Bonaminio, a halfback from 1952 to 1956. "R.C. [Owens] on one side and Baylor on the other side? Can you imagine? That would have been a helluva combination. But he was a basketball player."

Vokes was so taken by Baylor and Williams that he gave the D.C. duo the OK to invite other playground pals out West. So they asked Gary “One-Arm Bandit” Mays to join them in Caldwell. Mays was a recent graduate from Armstrong Tech High School and local legend in part for reasons related to Baylor. Despite losing his left arm as a five-year-old in a shooting accident, Mays became a multi-sport star. He attained hero status among his peers by shutting down the deified Baylor and knocking out previously undefeated favorite Spingarn in the 1954 city championship basketball tournament. More eye-opening: Mays, again with just one arm, was also regarded as the best schoolboy baseball player in the city ... as a catcher. Mays, who died in 2018, once lent me his incredible scrapbook of news clippings from his teens, which included a 1954 article from D.C.’s Daily News that said that Mays hit .375 his senior year at Armstrong and that “no one has stolen a base on him all season.” Mays had been holding out hope that he’d get a professional baseball contract. But with the school year already underway and no pro team having offered to sign him, Mays got on a train to join Williams and Baylor. The journeys of these three black buddies, transporting them over three days from a segregated, urban existence to a land full of white people and mountains—same country, but a different world—seems the stuff of cinema and literature.

“I’d never seen anything so beautiful,” Mays told me of his first glimpse of Idaho on the ride out. (Full disclosure: Mays was a personal friend and hero of mine who for the last 20 years of his life acquiesced to all my pleas to tell me stories from D.C.'s greatest generation of athletes.)

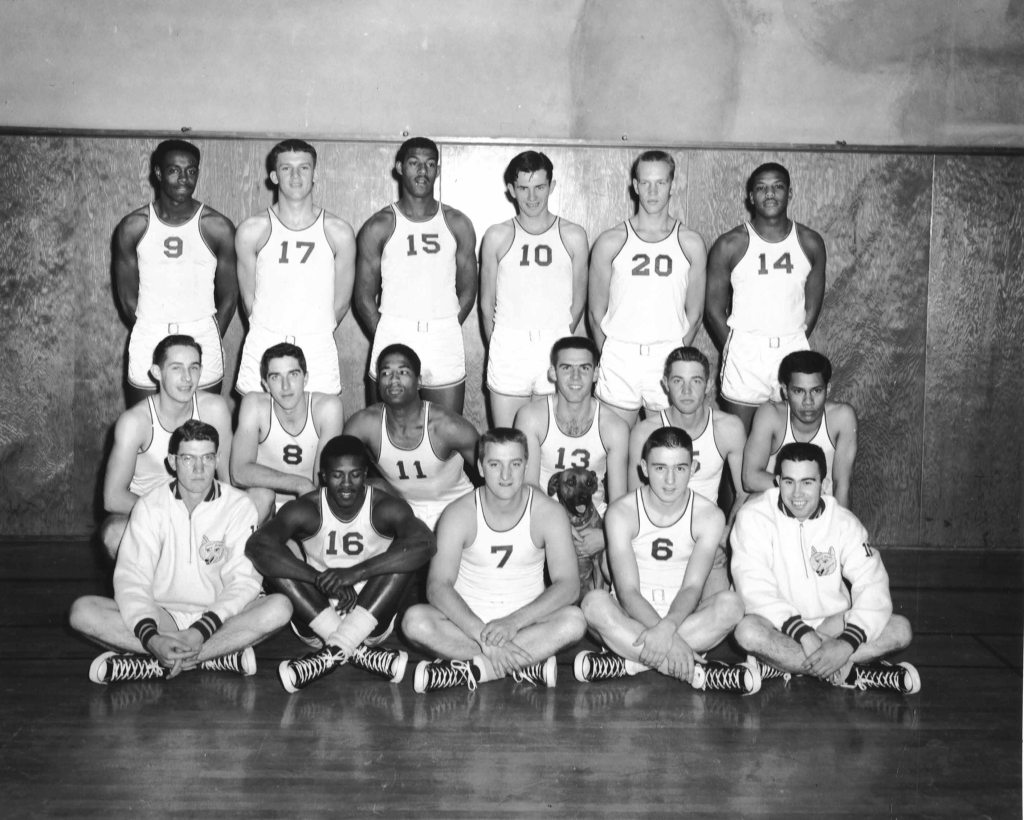

The C of I basketball team Vokes assembled, with six black players and a trio of D.C. freshmen led by Baylor, went 23-4 overall in the 1954-1955 season. The squad posted an 18-game winning streak and a 15-0 record in the Pacific Northwest Conference. That was the first time in school history they’d gone undefeated in league play. The team would go another 65 years—until last season, in fact—before posting another unblemished conference record. Baylor broke every major scoring record, averaging 32.8 points a game, and notching 53 points in a single game.

It wasn't how much Baylor scored as much as how he scored that dropped the most jaws. Everybody in the Caldwell gym was as wowed by the regular show the newcomer from D.C. put on as Jimmy Wexler was that night of their one-sided match game at Terrell Junior High. "You can't believe how high up he got when he shot," says Dick Hahn. "When you watched him, it was like he was shooting down at the rim, even from the top of the key."

Teammate Reynoldson remembers lots of humorous moments when locals on his squad and others from the Great Northwest first witnessed Baylor’s seemingly otherworldly gifts. Like the time an opposing coach ordered a full-court press defense to start the game. “They had these two guards that were just ballhawks, quick, good ballplayers, and they were all over our guards, and so we had trouble getting the ball down the floor,” he says. “So there’s a timeout, and Baylor says, ‘Just give the ball to me.’ And on the next inbounds, he takes it, dribbles all around and through their whole team, all the way down the court, and just slams it. I was laughing. They were good ballplayers, like I said, but no match. They didn’t have a chance against Elgin Baylor.”

Mays and Williams didn't start or put up big numbers, but according to Baylor and other C of I teammates, played beneficial roles that didn't show up on the stat sheet. Mays averaged just 1.7 points per game on the season, according to stats provided by the C of I athletic department. But his scrapbook also included a clipping from a Caldwell paper that lauded him and Baylor for performing “Globetrotter-like” halftime routines showcasing their dribbling and shooting skills at home games. Reynoldson and Bonaminio remember seeing Mays showcasing his unique hitting and throwing abilities as an invited guest at games of the minor league Boise Braves. "He'd hit 'em out of the park, and show the fans how he flipped his glove off to make the throws," says Reynoldson. "Gary was a star in his own right here." Williams didn’t play much, averaging just 2.3 points per game. But Reynoldson remembers him as "the team comedian" from their time together on the bench.

Baylor, in our recent conversation, said that his play at Idaho was greatly enhanced by always having Williams and Mays close by. “We knew each other and had played against one another on the playgrounds,” he told me, “so it wasn’t like I’m in a strange place so much. We like one another, we know one another. That made it easy.”

The locals and schoolmates made him feel at home, too. In Hang Time, Baylor wrote that he and his buddies couldn’t help but notice they were surrounded at all times by white people in Caldwell. According to the 1950 U.S. Census, there were 1,050 black people in all of Idaho, or about 1.7 percent of the total state population of 590,000. But when he looks back at those days, Baylor said, he feels as if they’d landed on the set of Leave It To Beaver, the sitcom with an all-white cast that debuted at the end of the decade. The only racial profiling Baylor noticed in Idaho was of a sort that amused him: Lots of white classmates, men and women, asked him for music recommendations or dance lessons. He always complied.

“It feels as if W.W. and I have wandered into a private and exclusive members-only club,” Baylor wrote, “but rather than feel intimidated or excluded like I do in D.C., I feel invited.”

The year ended with C of I being upset by Montana State, 78-76, in a preliminary round of the 1955 National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) tournament for small schools. But the amazing turnaround—the team had gone 13-14 the previous season without the D.C. invaders—and unlikely makeup caught the attention of Sports Illustrated. An article in SI's March 7, 1955 issue said that the school’s 1,000-seat arena went from being empty on game night (one game the year before Vokes’s arrival had total gate receipts of $2.40, the story said) to regularly sold out by the end of Baylor’s freshman season. But according to the piece, the key to C of I’s “seemingly miraculous” success was to give scholarships to players “whose scholastic abilities were not quite comparable to their athletic powers.” SI writer Gerald Astor specifically mentioned three black players—Baylor, Mays and Owens—as beneficiaries of the loosening of the alleged academic standards. He called Baylor and Mays “sensational recruits,” but indicated neither would have made the cut, grade-wise, at any of the Pacific Northwest Conference schools that the Yotes had pummeled all year.

“Burdened by personal problems or after-school work, both Baylor and Mays had marks that were well below the average of their high school classes,” Astor wrote. The reporter did say that school had provided tutors for all athletes, and that Baylor had “turned into something of an academic whizz as well as a basketball star as he brought in a string of B's in his first semester.”

In a 2008 interview with the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Baylor said he was still pissed about the vintage rumors that he’d only gone to Idaho because of academic issues at Spingarn.

"They always said I had bad grades and that was bull," Baylor said. "I never got a grade below a C. None of the white scouts came to our games."

But Idaho administrators clearly gave weight to SI's accusations that the school had bent academic standards to get the black players that turned the school into a winner. Tom Shearer, the C of I president, fired Vokes shortly after the SI story’s publication, telling the Idaho State Journal, a newspaper based in the city of Pocatello, that Vokes had to go out of “the necessity of keeping the athletic activity in its proper perspective with relation to the other departments of the college.”

Vokes was peeved by the dismissal, and didn’t hide it in interviews. "The administration evidently does not approve of my philosophy of winning," Vokes told the State Journal. "I cannot give up this philosophy that winning within the rules and the spirit of the game is important."

The D.C. contingent broke up and left the school after the administration jettisoned Vokes and signaled it would deemphasize the basketball program through an elimination of several scholarships. Mays turned down a personal offer from Abe Saperstein to join the Harlem Globetrotters and went back home. Williams also went back to D.C., and any thoughts about trying to find another college squad for him and Baylor were quashed when he was notified that he’d been drafted into the U.S. Army. He couldn’t get a deferment, and was deployed overseas while Baylor continued his school search. After his military stint, Williams got another shot at college basketball, this time at Virginia Union, the only school that had recruited both him and Baylor back in 1954.

Baylor, however, had no interest in going home when the Idaho experiment imploded. Even after just one season playing ball in Idaho, his renown in the Great Northwest rivaled his reputation back in D.C. In a 2012 interview, Baylor told me he’d made some demands that he felt would make him more comfortable. Just as Williams had found Idaho for him, Baylor wanted to share Seattle with friends who for racial and economic reasons hadn't been extended a college invite.

“I told them that to get me to go there, they had to take my friends, too,” Baylor says. “I knew the guys back home were good enough, and the coach wouldn’t be disappointed.”

Seattle University Coach John Castellani fell in love with Baylor, and gave him carte blanche to bring all the D.C. players out West he wanted.

They always said I had bad grades and that was bull. I never got a grade below a C. None of the white scouts came to our games.

Elgin Baylor

Mays and Williams were no longer available. So Baylor went home over the summer of 1955 and tried coaxing other playground pals to join him in Seattle. Francis Saunders, a former Spingarn teammate who’d recently gotten his high school diploma, told me in 2012 about Baylor showing up at his front door one night as fall approached. Baylor asked where Saunders was planning to go to college.

“I told him I wasn’t going anywhere, I would probably join the military,” Saunders recalled. “But he says, ‘I’m going to Seattle tomorrow. Come with me. I’ll pick you up!’ So I walk into the kitchen and say, ‘Mom, I’m going to college tomorrow!’ She got sad and said she couldn’t afford to send me. I told her, ‘Don’t worry, Elgin’s going to take care of it!’ And he did! The next day, Elgin came by and picked me up and we drove across the country. I went to college and that never would have happened without Elgin.”"

Baylor had already convinced another former Spingarn teammate, Lloyd Murphy, to also jump in the car in exchange for a scholarship at Seattle. The deal worked out great for all concerned.

Baylor sat out a season as per NCAA transfer regulations, but upon his return to the court was even more dominant than he’d been in Idaho. Baylor took over the Seattle team and immediately had everybody in the Great Northwest waxing as hyperbolically as Williams ever had. In a preview of the 1956-1957 college season that ran on Dec. 11, 1956 in the Eureka (Calif.) Standard, Al Lightner, an official with the Pacific Coast Conference and sports editor of the Salem (Ore.) Statesman, called Baylor “the greatest basketball player I have ever seen.”

In a 2012 interview, Castellani still gushed about his first big recruit at Seattle. “He did so many things nobody else did,” Castellani said, “things with the ball, like putting the ball behind his back on a fast break while cutting from his left to his right, and from a guy his size! He was way ahead of his time, and he brought all these things from the playground, things nobody had ever seen. I remember the coach at Portland put a sign up in their locker room: ‘If you’re going to stand around and watch Elgin play, then pay admission!’ That was perfect.”

Baylor led Seattle to the greatest season in school history in his second year on the team. The Chieftains made it all the way to the NCAA finals, facing Adolph Rupp’s Kentucky squad in Louisville. Baylor, playing with broken ribs and much of the night with four fouls, had 25 points and 19 rebounds, but Seattle squandered an 11-point lead and lost, 84-72. Despite the loss, Baylor was named MVP of the Final Four.

Castellani and Baylor’s run at Seattle ended in unseemly fashion, amid cheating allegations. As had happened in Idaho, Baylor’s upstart Seattle program got blown up just as it reached its highest heights, and the school’s pursuit of D.C. talent was again scapegoated. Mere weeks after Seattle’s appearance in the NCAA final, Castellani was accused of providing improper financial benefits, in the form of plane tickets, to recruit Ben Warley, a friend of Baylor’s from Stonewall A.C. The school's administrators quickly forced Castellani out. Seattle’s hoops program was put on probation for two years by the NCAA, and Warley, who would go on to a 10-year career in the NBA and ABA, was banned from ever playing alongside his buddy at Seattle. Even back then, the NCAA seemed intent on keeping kids who could use a break to get to college from getting one.

The firing of Castellani and probation left Baylor at a crossroads. If he stayed in school, the penalty would deprive Baylor, with only one year of NCAA eligibility remaining, of another shot at a national title. He declared himself a professional. The Minneapolis Lakers used the first overall pick in the 1958 NBA draft to take him.

Saunders stayed in school and made his mother proud by getting his bachelor of arts degree in English in 1961, according to Seattle's sports information director, Shaney Fink; Murphy got his B.A. in economics in 1962.

Williams Jr., who followed Williams Sr. into a successful business career in D.C., said his dad lost touch with Baylor in his later years, in no small part because Baylor stopped coming to D.C. But the elder Williams brought his old friend’s name up in conversations fairly often. Whenever anybody in the family even hinted that Michael Jordan was the best basketball player of all time, for example.

“That was Elgin in our household,” Williams Jr. said. “Nobody else.”

Williams Jr. also spoke up to defend Baylor for almost never visiting his hometown after college. “Dad said people complaining that Elgin never came home didn’t understand how bad it was for Elgin here, the pain he felt,” Williams Jr. said. ”Washington, D.C., was just a different town then.”

Despite the sudden and sad way their time in Caldwell ended, according to Williams Jr., his father never expressed anything but joy about their time so far from home. Williams Jr. says he often wondered what it was like for his dad and buddies to just transport themselves to such a different environment as teenagers. The son's wonderment was only intensified when he made his own trip to Idaho as a grownup.

"About 50 years after my dad was there, I went on a business trip with folks from the D.C. government to Idaho,” said Williams Jr., who like his father was a lifelong resident of the nation’s capital. “We were the only African Americans in the Boise airport. I gotta say, I felt weird in Idaho and I grew up in an integrated city! I can’t imagine what they felt like, from Spingarn and Dunbar in 1954! But, to hear Dad or Elgin or Gary, they talked about Idaho like it was the time of their lifetime.”

Baylor went on to win NBA Rookie of the Year in 1959, and was named First-Team All-NBA 10 times, and an NBA All-Star 11 times. He averaged 27.4 points per game over his career, which puts him behind only Michael Jordan and Wilt Chamberlain in career scoring. He still holds the record for points in an NBA Finals game (61 points in Game 5 of the 1962 Finals against the Boston Celtics) and series (284, also in 1962). Baylor also showed that he was done putting up with the systemic racism he’d endured during his childhood but had avoided out West: As a rookie, after a Charleston, W.V., hotel refused to give him and his black teammates rooms, Baylor staged what was likely the first civil rights-based walkout in NBA history. He sat out a Jan. 16, 1959 game in that city between the Lakers and Cincinnati Royals. Teammate and Charleston native Hot Rod Hundley asked him to change his mind about the strike. Baylor declined. “I’m a human being,” he told Hundley, according to Baylor’s memoir. “I’m not an animal put in a cage and let out for the show.’’

But Baylor had already left a historic mark on the game even before he’d left the Great Northwest: His play at College of Idaho and Seattle forced folks to recognize D.C. as a hoops hotbed. Proof of his impact on the basketball reputation of his hometown came in 1957, when Wilt Chamberlain, a Philadelphia icon and likely Baylor’s only rival for best baller alive at the time, spent a summer in the nation’s capital playing pickup on the city’s playgrounds.

Baylor’s hometown subsequently produced as much hoops talent per square mile as anywhere. Among the other NBA players born and reared in D.C.: Dave Bing, Adrian Dantley, Kevin Durant, Austin Carr, Johnny Dawkins, Sherman Douglas. (When the NBA named its 50th anniversary all-time team in 1996, Spingarn was the only high school that could claim two members, Baylor and Bing.)

“We didn’t ever think of Washington, D.C., basketball up here,” Sonny Hill, himself a Philly streetball legend and childhood friend of Chamberlain’s, told me in a 2012 interview about the fantastical Chamberlain/Baylor summer series. “Nobody did. It was just us and New York. Then Elgin Baylor came out and we all heard about it. He put D.C. on the map.”

Would all that have happened had Baylor not gone West as a young man? Williams Jr. said that a couple years before he died, his father pondered out loud his role in the momentous migration of basketball talent out of D.C. that started with him and Baylor, perhaps basketball's version of Lewis and Clark.

“One time Dad just started talking about Elgin,” said Williams Jr. “And he goes, ‘I wonder how long it really woulda taken the world to see the greatness of D.C. basketball if we hadn’t gone to that little town.' That was kind of powerful."

According to Mike Safford, now the sports information director at C of I, all of Baylor's scoring records at the school still stand, 65 years later, and to this day he's the only alum to ever make the NBA.