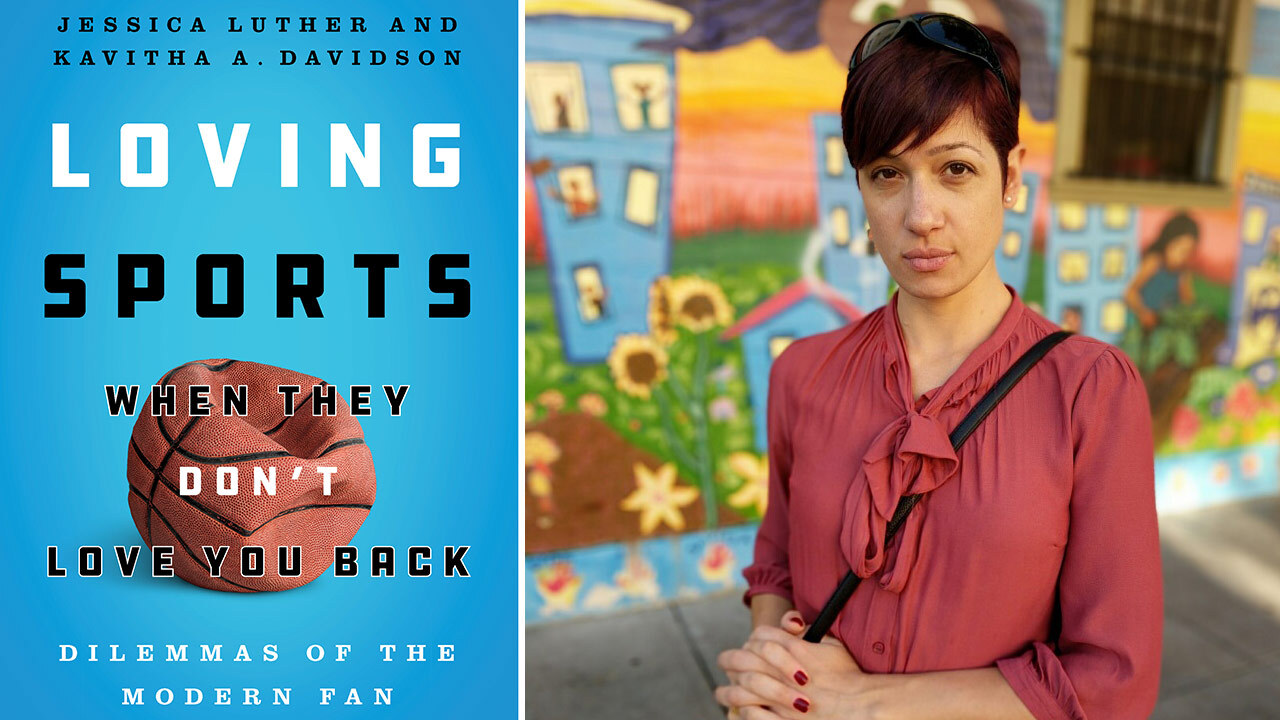

This excerpt from Loving Sports When They Don't Love You Back is published with the permission of the University of Texas Press.

Toni Smith-Thompson grew up in New York City and began playing basketball when she was 9 or 10 years old. She attended Manhattanville College, a small liberal arts college just outside the city. The school was predominantly white. Smith-Thompson is the daughter of a Black man and a white woman, and she identifies as Black. Halfway through her time at Manhattanville, 9/11 happened. There were, she says, “significant changes on the court after the attacks.” The American flag was added to the team jersey, and ceremonies were dedicated to alums who had died that day.

These changes paralleled her studies, which included courses on “the prison-industrial complex, military-industrial complex, [and] gender studies,” and furthered her development as an activist, she says. “Senior year, I became the co-captain of the team and at the same time was ... knee-deep in research on the impact that media has on our society and our consumerism.”

Then she had a conversation with her boyfriend, who, like Smith-Thompson, had a white mom and a Black dad. "We shared those experiences of living in a country, being born in a country that does not want you and has targeted you, but knowing no other home,” she says. “I really got clear that the way the flag and patriotism are used is not really representative of my life experience or my values or political beliefs, yet it was something that I was expected to do in order to play basketball. [But it] really had nothing to do with basketball.”

When her boyfriend asked why she was standing for the anthem and then challenged her answers, she couldn’t “shake what I felt like was really the truth: that I didn’t have to do this, I shouldn’t have to do it.” Smith-Thompson identified the basketball court as a specific place where she could practice those values. “I could kind of assert a different truth or a different way to engage in democracy,” she says, “and if I didn’t have the courage to do that, then what does that say about the kind of activist I say I am?” She was 21 years old.

And so, to protest the obligation to stand for the anthem, as well as the United States potentially going to war in Iraq, she decided to turn her back during the anthem. For two months she did this without much attention. And then she became the center of a national story.

On Feb. 26, 2003, the New York Times wrote a piece about her: “Player’s Protest

Over the Flag Divides Fans.” Manhattanville was playing at home against the Merchant Marine Academy, and Smith-Thompson believes a coach or player from a previous opponent had called ahead to let that school know about her protest. To say it didn’t go over well with the Merchant Marines is an understatement, and the result was something you rarely see in a Division III women’s basketball game: a sold-out crowd.

Smith-Thompson remembers lots of American flags in the stands, “cadets in uniform lined up along the sideline holding six foot flags,” and the taunting. “The whole game they were like, ‘Go back to Iraq, you bitch,’” she recalls. “Curses and all kinds of other slurs. And they weren’t really just directed at me, either. The slurs were aimed at the entire team.” Manhattanville won, 67-51.

I really got clear that the way the flag and patriotism are used is not really representative of my life experience or my values or political beliefs, yet, it was something that I was expected to do in order to play basketball. [But it] really had nothing to do with basketball.”

Toni Smith-Thompson

In comments she made to the media after the game, Smith-Thompson said: “A lot of people blindly stand up and salute the flag, but I feel that blindly facing the flag hurts more people. There are a lot of inequities in this country, and these are issues that needed to be acknowledged. The rich are getting richer and the poor are getting poorer, and our priorities are elsewhere.” When a member of the media asked if her protest (“a half-revolution of the body,” as Bill Pennington described it in the Times) would empower Saddam Hussein, Smith-Thompson replied coolly: “I doubt Saddam Hussein is watching me right now.”

The president of Manhattanville supported her, as did her family, her coach, and the Black and Latinx student caucuses on campus. Her teammates were less supportive. Recalling a team meeting about the issue, Smith-Thompson says: “We just ended up having to agree to disagree. Then I was not on great terms with most of my team after that.” There were two women on the team who had her back, standing on either side of her in the lineup before the game and holding her hand during the anthem. She received some credible death threats, even while she received mail from around the world supporting her.

It was six weeks of her life, she believes, that the news media focused on her, though she admits it is hard to remember the exact time frame. It was a very lonely path to take, as friendships fell off and she felt like a pariah on campus. There was no social media at the time, only her immediate surroundings. And it affected her love of the game. “I was so jaded by the end of that season that I didn’t want to do basketball anymore as a professional or other serious endeavor,” she says. “A lot of it was really tainted for me.”

However, this was the beginning of a journey that led her to become an organizer in the advocacy department of the New York Civil Liberties Union. And despite how hard her experience was, she believes that athletes who care about issues of social justice should use their platforms to draw attention to inequities and oppression.

“I think athletes certainly occupy a very unique and important place because sports are our biggest public gathering place," she says. "The importance of sports is embedded into the culture itself.”

But Smith-Thompson cautions that the message can’t get lost in the commodification of sport. “How do we retain ownership over our own messaging, so you don’t have a protest against police violence turn into a stand for something even if it means sacrificing everything?” she asks, nodding to Colin Kaepernick’s Nike ad. These are necessary critiques in the current climate of athlete activism.

This excerpt from Loving Sports When They Don't Love You Back is published with the permission of the University of Texas Press. It is available for purchase now.