About 16 million years ago in what is now Virginia, a long-snouted fish called a gar drifted through the water, stalking prey in the shallows, when a sinking lump caught the fish's eye. The opportunistic gar began sucking the lump into its long jaws and bit the side of the lump with its fence of teeth. Only then did the gar register that the lump was not a serendipitous meal from above; rather, it was poop. And so the gar went on with its day, and the half-bitten poop continued sinking to the seafloor, to be subsequently entombed in sediments.

This is a group of scientists' best explanation for a strange new fossil, which they described in March in the journal Ichnos.

If our poops outlast us, as they occasionally do, their fossilized forms are called coprolites. Every coprolite is a bit of a miracle, considering how quickly feces decays and disintegrates when compared to something as hard as bone. And like modern poops, coprolites come in many forms, depending on their ancient makers: round, cylindrical, bulbous, even spiraling. This particular half-bitten coprolite, which sort of looks like a potato that someone raked over with a comb, was unearthed from Lower Miocene deposits along the banks of the Pamunkey River. It was just over four inches long and took a familiar form: roundish on top and slightly flattened on the bottom, indicating the soft excretion came to rest on the substrate below.

A poop of this heft and this age could only have come from a select few organisms, most likely an ancient crocodile or cartilaginous fish, the authors reasoned in a section of the paper titled "Identity of the faecal producer." But many fishes produce spiral-shaped feces, thanks to the spiral valves inside their colons, and this coprolite was too long and cylindrical to resemble the average excretion from a shark. Two crocodile species from the Miocene have been found in this area, both of which could have produced a poop of this size and shape, the authors suggested. Based on past studies suggesting correlations between the diameter of a crocodilian coprolite and the body length of the crocodile who made it, the authors estimated the crocodile behind this poop was likely about 11 feet long.

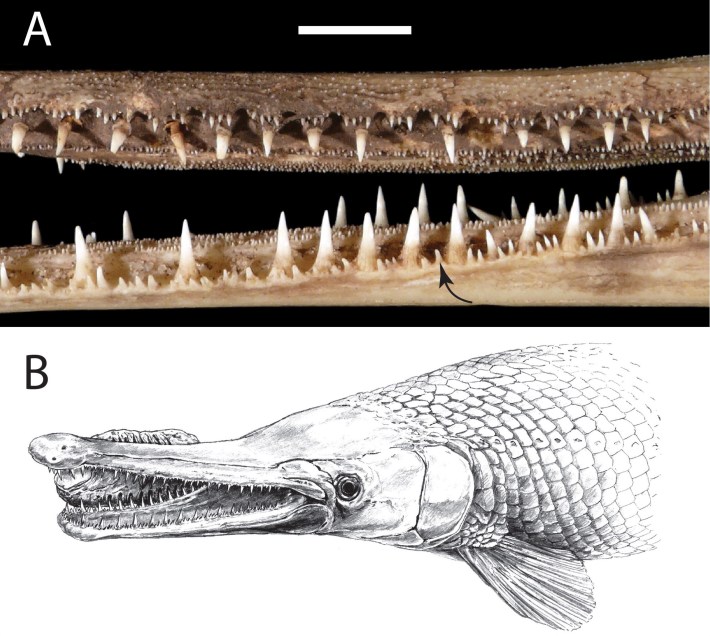

In the subsequent section—"Identity of the biter"—the researchers build a case that a gar in the genus Lepistosteus was the culprit. They observed that the gouges in the coprolite are gently curved, suggesting the bite was glancing and from the side of the mouth. They also noticed smaller gouges nestled in between some of the larger marks, suggesting the biter had two different sizes of teeth—just like a gar. The authors note several other creatures with teeth that could have been responsible for such marks, such as a sandtiger shark, porbeagle shark, or a salmon shark. But these clues, combined with a gar's strategy of capturing prey, most strongly suggest a gar was behind the bite. And though there is nothing wrong with coprophagy—to each their own!—gars are not known to eat poop, suggesting the fish lunged at what it thought was prey and then quickly spat it out.

What have we learned from all of this? Millions of years ago, a gar had a bad, bad day. Coprophagy is not for everyone. And every poop has a story to tell, if only we look at it very closely.