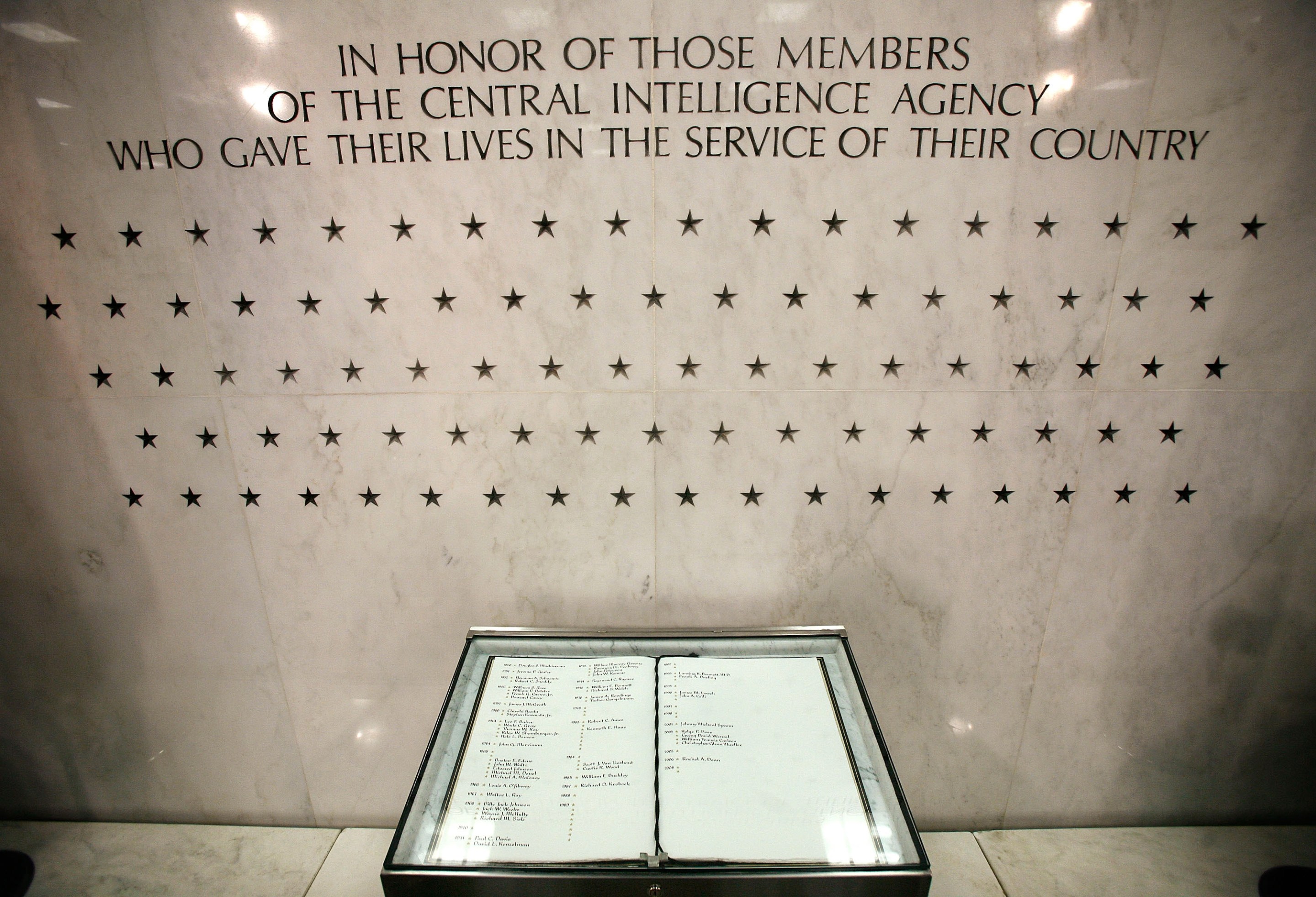

For some years now, Havana syndrome has been something of a Rorschach test. First reported on in 2016 in Cuba, the affliction is generally described as a wide-ranging set of medical symptoms that U.S. foreign service members, primarily those in the CIA, have said they experienced at locations all over the world. Initially, the government thought the maladies could be caused by sonic weapon. More recently, an investigation raised the specter of giant Russian microwave beams. Mass hysteria has also been a leading theory. Any one person's chosen explanation can tell you a lot about that person's gullibility and regard for one of the most dishonest self-interested segments of the U.S. government. This is how we know that Puck News correspondent Julia Ioffe is just awful at her job.

Before we get to Ioffe, it's important to understand how Havana syndrome coverage has metabolized in the media. Most news reports and stories about Havana syndrome over the years—and there have been so very many—try to balance the existence of the symptoms, that real people say they are experiencing, with the near complete lack of evidence that any person or nation is deliberately causing it. In recent months, a number of leading publications attempted to shed some light on the issue, which was decisively hoisted up the priority list by the Biden Administration and the United States Congress, which unanimously passed a bill providing aid for the syndrome's alleged victims. Earlier this month, New York magazine published an explainer titled "The Havana Syndrome Mystery and How the U.S. Plans to Solve It." The explainer allows for the possibility of the symptoms being caused by attacks, but tempers the theory with findings from the State Department's own research.

In 2019, the State Department requested that the National Academies of Sciences research the symptoms to determine how to collect data on future cases. The resulting report was frustratingly inconclusive.

Part of the problem, report co-author Jeffrey Stuab told BuzzFeed News, was that the NAS team “didn’t have information about individual people, including who was first affected, who was later affected, what their connections were.” However, he added: “Even if we had all the security clearances to see everything about everyone, there would be holes in the information.” While the report did determine that a microwave attack could cause dizziness and depression, one author described this idea as “science fiction.”

New York

Last month, the BBC published a story on Havana syndrome, delving more deeply into the possibility of microwave technology and its history of use during the Cold War. If anything, the report treats the possibility of a microwave weapon more generously than it should, perhaps, given that scientists have largely repudiated the theory, but it concludes like this:

The debate remains divisive and it is possible the answer is complex. There may be a core of real cases, while others have been folded into the syndrome. Officials raise the possibility that the technology and the intent might have changed over time, perhaps shifting to try and unsettle the US. Some even worry one state may have piggy-backed on another's activities. "We like a simple label diagnosis," argues Professor Relman. "But sometimes it is tough to achieve. And when we can't, we have to be very careful not to simply throw up our hands and walk away."

The mystery of Havana syndrome could be its real power. The ambiguity and fear it spreads act as a multiplier, making more and more people wonder if they are suffering, and making it harder for spies and diplomats to operate overseas. Even if it began as a tightly defined incident, Havana syndrome may have developed a life of its own.

BBC

In July, the New Yorker wrote about a slew of new Havana syndrome cases in Vienna. The report contends with the mass psychogenic illness theory and the popular new microwave theory, though it takes pains to note that there is no evidence for the latter:

Senior officials in the Trump and Biden Administrations suspect that the Russians are responsible for the syndrome. Their working hypothesis is that operatives working for the G.R.U., the Russian military-intelligence service, have been aiming microwave-radiation devices at U.S. officials, possibly to steal data from their computers or smartphones, which inflicted serious harm on the people they targeted. But American intelligence analysts and operatives have so far been unable to find concrete evidence that would allow them to declare that either microwave radiation or the Russians were to blame.

New Yorker

This brings us to a story published yesterday by Puck, a new digital media company that promises readers, somewhat ominously, that its coverage "begins where the news ends." Ioffe's story not only leans heavily on cherry-picked evidence to support the idea that Russian microwave weapons are behind the attacks on U.S. spies, but does so in a naked attempt to gin up support for U.S. retaliation against Russia.

Ioffe wrote a big, credulous story about Havana syndrome for GQ in 2020, and apparently has been eagerly on the hunt for further evidence to support her own conclusions. In the Puck story, she is at least transparent about where her surety is coming from: Her own powerful hunch. She writes in her Puck story (for full effect please read the following in a classic noir detective voice): "I always suspected that these illnesses were the product of deliberate attacks and that the Russian government was behind them—it was exactly the kind of weird thing they’d be both into and capable of—but it was early days, and no one seemed to know much of anything."

It is genuinely useful for readers to know that Ioffe is seeking to validate her priors. Less useful is her lack of rigor in doing so. She tells the story of a former CIA officer named Marc Polymeropoulos getting "hit" while working in Russia, which she deems a "tantalizing clue" that the Russians are responsible. She then runs through a list of other recent "attacks," none of which took place in Russia. She writes that the report commissioned by the State Department "concluded that the syndrome was real and 'unlike any disorder reported in the neurological or general medical literature.' It also said that mass psychosis was an unlikely cause and pointed to directed energy, specifically pulsed microwaves, as the most plausible cause of the symptoms."

In fact, the study was not nearly as conclusive as this. The authors did not write "that mass psychosis was an unlikely cause," but that due to a lack of data "the committee was not able to reach a conclusion about mass psychogenic illness as a possible cause of the events in Cuba or elsewhere." And in a statement sent after the report was released, the State Department said: "Among a number of conclusions, the report notes that the ‘constellation of signs and symptoms’ is consistent with the effects of pulsed radio frequency energy. We would note that ‘consistent with’ is a term of art in medicine and science that allows plausibility but does not assign cause.”

Ioffe is clearly seeing what she wants to see: A spy drama where the bad guys are targeting the good guys and, by golly, we need to do something about it! The possibility that this could be any more complicated, or even dead wrong, is an idea too inconvenient for her to entertain. Ioffe expresses herself most clearly in the inclusion of the following quote from an anonymous Democratic staffer: "Why would we question the sanity of people who are highly trained to handle some of the government’s most sensitive information and negotiations?" The simplemindedness of this question would be almost sweet, were it not in service of agitating for the U.S. government to retaliate against another country based on zero evidence.

At the end of the story, Ioffe allows an anonymous CIA member to make the call to action explicit. "Some in the intelligence community are getting restless, eager to see the people who wounded so many of their comrades punished," she writes. "Even if the intelligence is 'medium confidence,' one member of the community told me, that should be enough to go on. 'We got bin Laden with medium confidence.'" I can think of a few other examples in which the United States took drastic action based on "medium confidence" that should give any journalist with half a brain some pause before becoming a willing CIA mouthpiece.

Is Havana syndrome real? Could it be the work of the Russians or some other shadowy enemy? Probably not, but who the fuck knows? Ultimately, as Ioffe's story and the U.S. government's response to the phenomenon prove, those questions don't really matter. What matters is what all of this hysteria and credulous coverage of the Havana syndrome has produced, which at this point is: a comprehensive healthcare package for CIA agents, and, more importantly, the return of a Cold War-era boogeyman for the agency to bravely stand up against. One would like to think that it shouldn't be that easy for one of the most evil, dishonest organizations in the history of the world to craft its own self-justifying narrative, but for as long as reporters like Ioffe are willing to put in the work it will be.