One of the benefits to a Pal subscription at Defector is a daily afternoon email newsletter that includes a few bonus features not found on the website. Among those extras is a weekly Guy Remembrance from David Roth. This particularly good one, about an obscure Detroit Tiger and punk rocker named Jim Walewander, is being republished on the site.

First there is the factoid, but I should tell you how it got there. In 1988, at the beginning of a brief and retrospectively poignant boomlet in baseball cards, Score rolled out its first set. The photos on the front were decent—not at the levels of high-gloss swankery that Upper Deck would claim, but far more engaging than the blurry/dusty norm that Topps and Fleer and Donruss had settled upon—and I appreciated that.

I was also ten years old, which meant I appreciated anything new having to do with baseball, anything new I could consume or collect or memorize or just kind of rotely sort. And what was newest on those Score cards was the text on the back, which was not the thumbnail scouting reports that Donruss offered or the careless grab-and-go media guide factlets on Topps cards but some rather startlingly well-wrought little stories about the player on the front. They had sources and paragraphs and paid off on the conceits in their little ledes and just about every player whose career record left room for text got one. Consider, for a moment, that there were 660 cards in that set, enough that even backup infielders and relievers and lower-rung September call-ups got cards. It is enough, even, that Jim Walewander got one.

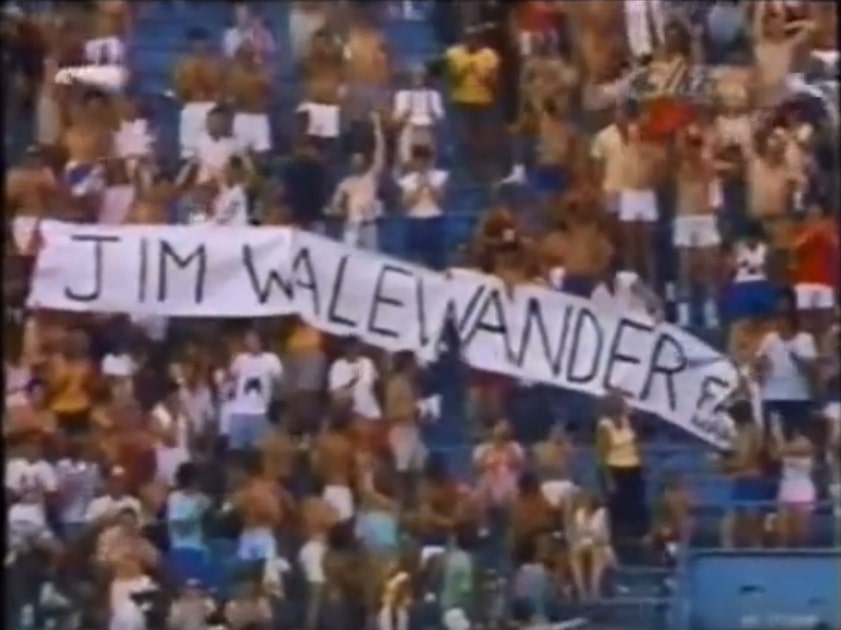

And now we’re to the factoid. There wasn’t much to say about Walewander as a player in 1988. He had just had his first 54 at-bats in the majors and saw most of his action pinch-running and moving around the infield. He hit one homer, which wound up being a game-winner, and would never hit another one in the majors. He would play a similar role with the Tigers for a little while, then diminishingly smaller ones with the Yankees and Angels, and then was done. It took him parts of four seasons to play in 162 games, and he made just 280 plate appearances in those. The first two numbers of his career OPS are both five; he is a Guy, in my estimation, but mostly because I remember him. And I remember him mostly because whoever wrote his 1988 Score card mentioned that Walewander “became an instant legend in Detroit for his devotion to an obscure punk-rock band called The Dead Milkmen.” On the day that Walewander hit his only homer as a big leaguer, the band took him up on his invitation to visit Tiger Stadium. He’d invited them after seeing them perform the night before. The band reportedly spoke to Sparky Anderson briefly, which is something I enjoy thinking about.

For someone whose playing career peaked when he was a 25-year-old rookie pinch-running specialist for a Tigers team that lost in the ALCS, a great deal was written about Walewander, who generally comes off as a goofy, funny dude despite, for instance, Mitch Albom’s exhausting attempts to spin him as a wacky comic figure. "People look at me and expect to see a clown," he told the Washington Post’s Jane Leavy in ’87. "I'm no clown." He was just who he was: someone who shopped at thrift stores and read books and knew both his role and how tenuously and temporarily it was even his. “When you go 27 days without an at-bat, you're not going to buy an apartment,” he told Leavy. “I'd go to the locker room every day and check to see if my uniform was still there and finally one day it wasn't.”

I didn’t know anything more about Walewander at the time than I could learn from his baseball card, and I didn’t know enough about how heritable athletic traits work to know that the type of baseball player I would become myself was kind of a washed-out version of the one he maxed-out to become. I did start seeing a Dead Milkmen video on MTV the next year, though, and got my parents to buy me one of their records. I can’t give Walewander credit for my thrift store habits, though Leavy’s story makes it sound like we have passingly similar taste in shirts.

But there was something about that throwaway detail on his throwaway card that I kept, which was the sense that even the least significant players had stories of their own, and were people, and so might surprise you. “He doesn't have much ability, but he loves to play,” Sparky Anderson told Leavy. “He's got that look that everybody wants to have. He's what the game is all about. It starts with dreams.”