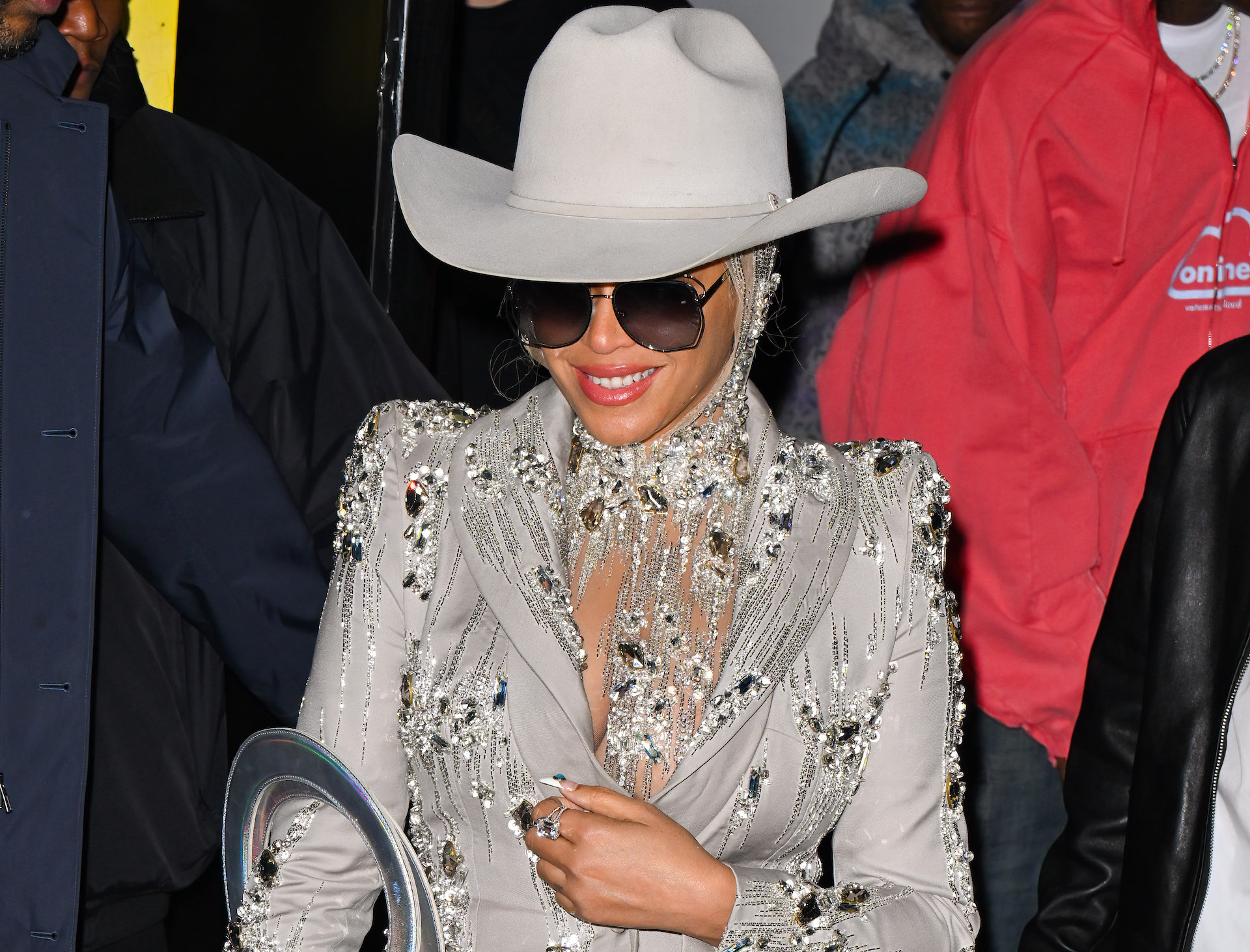

A sizable chunk of my weekend, along with much of the internet's it seems, was spent listening to and/or talking about Beyonce's new album, Cowboy Carter, a country western–infused "Act II" to Renaissance's disco "Act I." Technically, Beyoncé first teased the record with a Super Bowl commercial that led into the release of the album's first two singles. But in a lot of respects, this extended dalliance with country has been building since Lemonade's "Daddy Lessons" from 2016, particularly her performance of it at that year's CMA Awards with the Chicks—a moment notable for the cool reception the performance got from the country vanguard in the room, who were not particularly receptive to Beyoncé or the Chicks. Beyoncé even alludes to that reaction at the CMAs, and how unwelcome she felt there, as a pivotal point for her, which led to the making of this album and her deep dive into the history of black country music.

Beyoncé is one of the best marketers in all of pop, and she is particularly adept at using history, nostalgia, and tastemaking to better infuse her music with an air of importance and significance that might not always have been there. It's my opinion that she, even more than Taylor Swift or Britney Spears, is poptimism's crowning achievement: the proof of concept that mainstream pop music was not only worth loving out loud and taking seriously, but should be treated as serious art in and of itself. I compare her trajectory to Steven Spielberg's. He first became successful by being the most dependable director of blockbusters, making movies that were accessible, big, full of wonder, and appealing to the whole family—movies that regularly topped the box office but rarely earned mention during awards season. Then he made Schindler's List, won Oscars, and became Important. From then on all his movies were appraised with a weight and seriousness that had been refused to him prior.

For both Bey and Spielberg, part of the delayed critical acceptance came from the fact that, over time, the people who grew up with them eventually became the critics and were able to validate them in the critical regard; the other part was that the criticism establishment relinquished some of that stuffiness over what is or isn't serious. Beyoncé's turning point came with her 2014 self-titled album, and with Lemonade she cemented herself as not just a hitmaker, but as an artist worthy of the widest but also closest attention and appreciation.

With that said, sometimes she just makes good songs and there's not all that much deeper to it. Throughout the weekend, I watched early reviews come in that declared Cowboy Carter a reclamation, a revolution, a resurrection for country music and specifically for black country music. In fact, it seems critics are falling over themselves to give it as much import as they can muster. I can understand the desire to want things to be important, particularly when they're so massively successful and popular. Nobody wants to be left out of the celebration and everyone wants to be able to say they appreciated the biggest pop stars in their prime before that prime inevitably ends. But listening to the actual music, I felt neither reclaimed, revolutionized, or resurrected.

About the album itself, Cowboy Carter is more like a Disney tour through the genre, at least when it's actually staying within the bounds of it. (In fact, it's hard to even classify the album as a whole as country, except maybe in the way that early Taylor Swift albums were country.) There are lots of acoustic guitars, piano organs, banjos, and harmonicas, and it's a folksy good time in genuinely enjoyable ways; the songs are ear candy, charming and sweet. And eventually, some of the songs even reach transcendence for a moment. But as far as a reclamation, I'm not buying it.

Beyoncé has always excelled at using the aesthetics of black counterculture to tie her work into a rich, revolutionary tradition, but without any of it going much deeper than appearances. Cowboy Carter's version of this comes from the promotional posters that hearken back to the Jim Crow–era chitlin circuits. Here she has the pioneering black woman country singer Linda Martell appear on multiple tracks to connect her to a lineage of black women whom the genre has overlooked. It's great for Martell, who gets some much-deserved attention for her history and (hopefully) music. It's also good for current black women in country like Tanner Adell, Brittney Spencer, Tiera Kennedy, and Reyna Roberts, who also get a boost from the link to a megastar like Beyoncé. But when those artists are all smushed together on one two-minute song ("Blackbiird"), or otherwise hidden in liner notes or backing vocals, while established stars like Miley Cyrus and Post Malone get their own showcases ("II Most Wanted" and "Levii's Jeans," respectively), you can't help but notice less reclamation of an under-appreciated tradition and more gaming of the pop/country streaming charts.

I'm not totally sure what the point of all of this even is. Ostensibly, it's about remembering the black roots of country music that have been erased by country music's current mainstream configuration. I can understand that. I can also understand that, as a black girl from Houston and with Louisiana roots, she presumably wants to make clear that country music is as much a part of her lineage as soul or funk or hip-hop. Here's the thing, though: Anyone who understands music can already see the way country music is still infused within black music, whether it's Goodie Mob or UGK or Nappy Roots' "Po' Folks" or Baby Boy Da Prince's "The Way I Live" or Young Thug's country-influenced album Beautiful Thugger Girls. There's Tracy Chapman. There's Anthony Hamilton. And to this day there are of course even more black artists literally fighting for their place within the restrictive confines of the country genre that could not make the cut of this Beyoncé album. None of this announced itself, or asked to be recognized by the establishment; it's just a reflection of how much country music impacts the music and the lives of many Southerners. And maybe that's where this comes off as a little artificial to me: that neediness for recognition, or, even worse, the exploitation of that desire for recognition for the self-aggrandizement of a megastar who hardly lacks for attention and acclaim.

But again, if the worst thing I can say about an album is that it's merely good, what are we even talking about here? Even the worst song on here, a cover of Dolly Parton's "Jolene," complete with a Dolly intro of course, is interesting in the little twist Beyoncé gives it to differentiate it from the original, even if the song falls flat. But I also recognize that, particularly for a star of Bey's caliber, this music has the simultaneous duty of selling the artist as a product.

Beyoncé deserves credit for experimenting and changing things from album to album, but it's worth acknowledging that much of it is geared toward world domination, the domination of every conceivable market. With Cowboy Carter, Beyoncé seems to want to force all those people in the audience of the CMA Awards into taking her seriously by using this album to convert all of their kids into fans of hers. Appreciating Beyoncé's move here is a little like congratulating Nike or Netflix for successfully broadening their consumer base. It may certainly be respectable but it's not important or revolutionary, unless what qualifies for revolution is the expansion of Beyoncé's bank account.

Truth be told, the best version of this album is the second half, which feels less beholden to its mission statement; it's a lot looser and more fun. This stretch starts with "Ya Ya," a funky Tina Turner–coded jam built on a bed of "These Boots Were Made For Walkin'," goes to the excellent country bounce of "Riiverdance," and to "Tyrant," the album's one club record. That run is where Cowboy Carter manages to shake free of the burdensome Importance and actually soars. It's just too bad that fun and flying don't seem to be enough for Beyoncé albums these days.