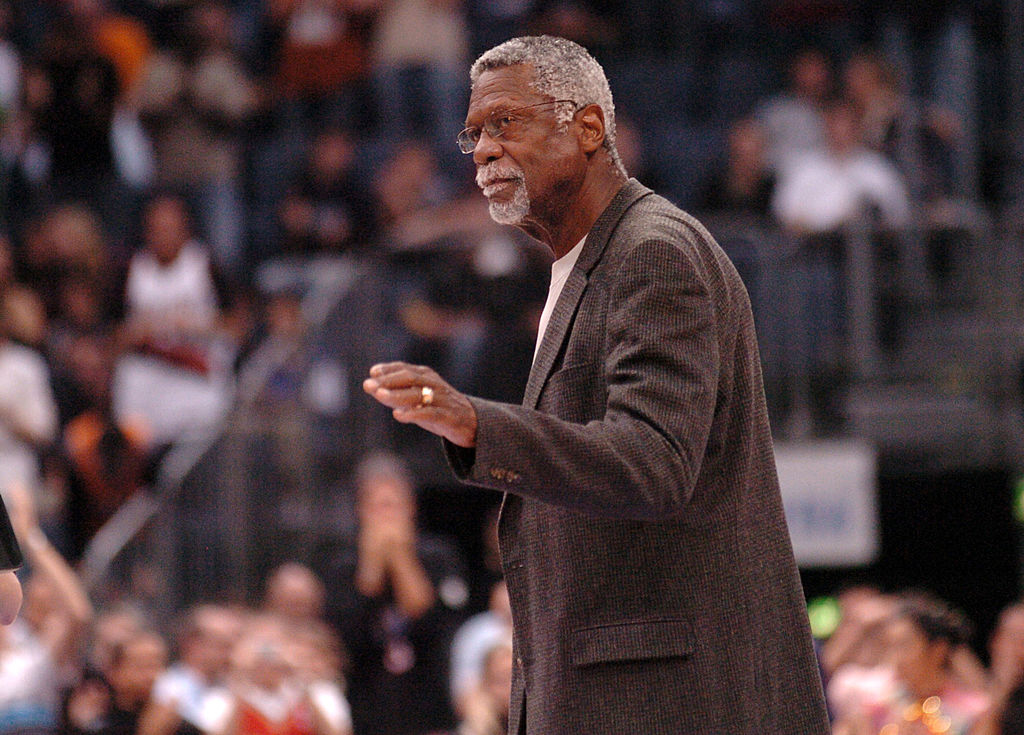

Bill Russell's job was playing center in the NBA. He was quite good at it. Half a century after he stopped doing it for a living, I'm struck by just how thoroughly Russell had sketched out—and satisfied—the description for that same job as it exists today. We're no stranger to historical slander here at Defector, aimed at both the legends themselves and the wan horde of milkmen and accountants that backdropped their feats. But I have enjoyed learning about Russell, through both the grainy black-and-white footage and his own eerily prescient reflections on basketball. Whether playing or talking hoops, Russell displayed the purest insight, piercing through box score pomp and latching onto the things that actually helped his team win the game. He had both a crystalline understanding of where he needed to be on the floor and the overbearing physical tools to occupy those spots on momentary notice. It's just as clear that the mental and physical core of Russell's greatness—a mastery of other players' tendencies, and a complete x-y-z axis control of the hardwood—are embodied in the best defenders of the contemporary NBA, too.

When it comes to players I'd never gotten a chance to watch, I trust the testimony of Ben Taylor, who does honest cross-era statistical work and also eats enough tape to appreciate these players in all their granular moment-by-moment excellence. His 2018 piece on Russell, whom he slotted fourth all-time, is worth your time. It's the kind of writing that's as interested in Russell's impact on the Celtics relative defensive rating over a decade as it is on a single defensive switch he executed one time. Taylor hailed him as the best team and man defender in his day. He charts the uncanny offensive nosedives of Russell's fellow superstars when guarded by the Celtics great. The data is as convincing and as towering as the legend.

What popped the most about Russell relative to his peers—a mobility that warped offenses in anticipation of what he might do, a spring-loaded second-leap, the versatility to stop a range of threats, grab-and-go eagerness to flip a stop into a counterattack in transition—is all mandatory for today's best defensive bigs. Watch Russell smoothly switch onto and stymie Oscar Robertson or Jerry West on the perimeter and it's hard not to think about Bam Adebayo putting the shiftiest guards and wings of the present day into timeout. See Russell engulf a doomed layup attempt and lead the break and, aside from some era-specific quaintness—he's carefully watching the ball as he dribbles—it might as well be Giannis tearing down the floor, far more coordinated than anyone of that stature has any right to be. Hear Russell break down the way he toyed with the offense's tendencies in 1963 and it's tough not to be reminded of the games that Draymond Green plays every time he blows up a two-on-one fast break:

The psychology in defense is not blocking a shot or stealing a pass or getting the ball away. The psychology is to make the offensive team deviate from their normal habits. This is a game of habits, and the player with the most consistent habits is the best. What I try to do on defense is to make the offensive man do not what he wants but what I want. If I'm back on defense and three guys are coming at me, I've got to do something to worry all three. First I must make them slow up or stop. Then I must force them to make a bad pass and take a bad shot and, finally, I must try to block the shot. Say the guy in the middle has the ball and I want the guy on the left to take the shot. I give the guy with the ball enough motion to make him stop. Then I step toward the man on the right, inviting a pass to the man on the left; but, at the same time, I'm ready to move, if not on my way, to the guy on the left. I'm giving away all my secrets.

Sports Illustrated

Hundreds of big men have passed through the league between Russell's era and the present day. Plenty of them have been bigger than him. Some of them moved quicker than him. Few thought quicker than him. The ones who managed to blend all those traits wound up generational. Kevin Garnett, a personal favorite of Russell's, might be his clearest evolutionary successor, a full-spectrum force who had something like the same motor and mobility but was souped up with aughts-grade ball skills. Garnett and Russell exemplified that mix, which now might as well be the holy grail of center prospects: rim protection and switchability. (Hello, Evan Mobley.)

It's crueler world out there for basketball's big lugs. Now that the floor has been stretched taut by shooting at all positions, the modern big man can be picked on in any number of ways—made to bumble through screens, to sprint vast distances toward corner snipers, to dance with sadistic dribblers. The standards are higher. The margins are finer. Teams take these big guys and run them through ever-finer sieves to find the outliers in balance, agility, and processing speed. Bill Russell had all that down pat before the game even demanded it. That meant he stood out even starker in his own day. Maybe it's why it seemed all too simple to him sometimes. "Analyze it—it's a silly game," he said. "I'm also a silly man because I enjoy it."