In D.C. sports lore, Bob Short is sort of the Sandy Koufax of louses. Short wasn't in town for long: He owned the Washington Senators for under three years before teamjacking them to Texas in 1971. Yet as noted high up in Short's 1982 obituary in the Washington Post, in that short stay he established himself as "one of the most reviled sports figures in Washington's history."

He's been gone for half a century. Yet lots of baseball fan who weren't even alive when he fled D.C. can still tell the tale of the dishonest carpetbagging cheapskate owner who took baseball out of the Nation's Capital and left such a stink on the city that lots of less-populated and -moneyed metroplexes got MLB franchises before the game came back to town.

Short’s first sporting proprietorship came not in D.C. and not in baseball. But as an owner of the Minneapolis Lakers in late-1950s, Short flaunted the same cheapness and disloyalty that would later poison his legacy in Washington. He had spent time in D.C. in the 1940s, briefly serving as a federal prosecutor in D.C. after attending law school at Georgetown. But he returned to his native Minnesota after a military stint in World War II and ran a successful trucking business. In 1957, he led a group of Minneapolis businessmen that cobbled together $150,000 to acquire the Lakers. Short had promised previous owner Ben Berger, who’d declined bigger offers from out-of-town groups, that he’d keep the team in the Twin Cities. But Short, once described by a minority partner as a guy who would “fight you for a nickel,” quickly decided to cut the team’s budget by getting rid of higher-paid players. He sent the team’s promising young center, seven-footer Walter Dukes, to the Detroit Pistons, where he'd go on to average a double-double over an eight-year career.

Luckily for Short, Elgin Baylor came along a year later to save what was now the league's worst team. As the overall top pick in the 1958 NBA draft, Baylor took the Lakers to the NBA Finals and won rookie of the year, bringing in enough fans along the way to keep Short solvent.

Short’s frugality was as famous as his disloyalty, and at times that penny-pinching endangered his players. To save money on commercial flights, he had acquired an old DC-3 prop plane that was reported to be a converted WWII-era cargo hauler. In January 1960, the Lakers' geezerly aircraft suffered a catastrophic failure of its electrical system on a flight home on a snowy night after a road loss to the St. Louis Hawks. After flying essentially instrument-free for three hours, and getting his bearings by occasionally sticking his head out of the plane's cockpit window after precipitation reduced his visibility from the front windshield to zero, pilot Vern Ullmann saw the tops of corn stalks peeking over the deep snow in a field in the town of Carroll, Iowa. Figuring that patch of farmland was everybody’s last best shot at survival, he took the plane down for a landing. Less than a year after Buddy Holly crashed into an Iowa cornfield during a blizzard trying to get to Minnesota, the Lakers crashed into an Iowa cornfield during a blizzard trying to get to Minnesota. Unlike the day the music died, however, everybody on the Lakers' plane survived.

“I thought we were dead,” Hot Rod Hundley told a reporter in Carroll after deplaning. Lakers players blamed the crash on the plane being past its prime. Short was not on the flight. But within hours of what would have been the greatest tragedy in U.S. sports history being barely averted, Short told the Associated Press that his team will continue flying to road games, “probably using the same craft.” Even more amazingly, Short followed through and had the old plane repaired at the crash site. He then convinced Ullmann to get back in the cockpit and fly it out of the cornfield, and put it back to work carrying the team within weeks.

The first flights were to the West Coast for neutral-site games in California that Short had arranged. Short warned his team that any player that didn’t board the plane would be cut. He was already scouting for a new home for the Lakers.

Short broke the pledge he’d made and moved the team to Los Angeles in time for the 1960–61 season. He personally stayed behind in Minnesota and sent general manager Lou Mohs out west with only one player (Baylor) still under contract, and no funds to put the organization together. According to a 1985 Lakers retrospective in the Los Angeles Times, Short’s only instructions for Mohs were: “Call me for anything but money.” Mohs had to use his own cash to buy the basketballs used in practice and provide furniture for the team’s offices. He was able to keep the operation afloat by giving his wife and kids such chores as washing uniforms, counting attendance, and even feeding the players.

Because of Baylor, the Lakers won consistently and quickly became the toast of Southern California. In 1965, after the team’s fourth NBA Finals appearance in six years, Short cashed out: He sold the Lakers to Jack Kent Cooke for $5,175,000, and made Cooke pay entirely in cash.

Short tried his hand at politics after the sale, running for Minnesota’s lieutenant governor in 1966, then taking a post as national treasurer of the Democratic Party during the 1968 presidential campaign of fellow Minnesotan and friend, Hubert H. Humphrey. Every campaign he touched was a loser, so he got back into sports ownership. When he heard the Washington Senators, the perennial American League doormats, were up for sale in 1969, Short put together an investment group and became its leader. His offer of $9.4 million beat out bids from Bob Hope and all other suitors. Short was headed back to the Nation’s Capital. Whether or not the locals were aware of Short's history, they were condemned to repeat it. Short promised the locals he’d keep his new team in town, but never pushed to renegotiate the Senators' lease of RFK Stadium, which was set to run out in 1971. The Washington Post and Sporting News subsequently investigated the deal Short made to land the Senators, and reported that he had put up just $1,000 of his own money, while also getting his partners to borrow more than $1 million from his trucking company at a whopping 9.4 percent interest rate.

The on-court successes of the Lakers during his reign had clearly gone to Short’s head. He immediately installed himself as Senators general manager and told players to expect pay cuts, not raises. Despite the team’s historically lousy past performances, he instituted the highest ticket prices in the major leagues. Under Short it became much cheaper to watch the perennial powerhouse Baltimore Orioles about 45 minutes to the north than to attend a game of the lousy Senators in D.C.

Short quickly began pleading that his group was undercapitalized, just as his operation was when he took over the Minneapolis Lakers. And he started making the same cheapskate business moves that crippled that team. According to Washington Post legend Shirley Povich blasted Short for making the Senators "the only team in the league billed for the owner’s private jet, with co-pilots."

At the end of the 1970 season, he sent a pair of future All-Stars, shortstop Eddie Brinkman and pitcher Joe Coleman, alongside Gold Glove third baseman Aurelio Rodriguez, to the Detroit Tigers and got Denny McLain and a gang of mostly scrubs in exchange. The trade made no baseball sense for Washington. So Short, still serving as GM, had nobody to blame. He was known to be an admirer of McLain, a two-time Cy Young Award winner who was on a downhill slide and by the time of the trade had a record of mysterious injuries and behavior troubles. McLain had just three wins in 1970, plus suspensions for setting up a gambling operation, bringing a handgun onto an airplane, and dumping a bucket of ice water on sportswriters in the clubhouse.

McLain was predictably horrible on and off the field with his new team. He went 5-22 on the season. No MLB pitcher has had more losses in a season in the 50 years since. He was also the confessed leader of a clique of conniving Senators players that manager Ted Williams, the biggest draw the organization had, called "the Underminers Club," since they'd spent the season devising ways to get Williams fired. McLain failed in that, too.

Conspiracists later suggested that every move Short made was designed to grease the wheels to get the Senators out of D.C. He arranged the one-sided deal with Detroit, it was widely believed, only in exchange for a pledge from Tigers owner John Fetzer that he’d support any attempt to move the Senators.

Baseball fans in D.C. already had lots of reasons to be fatalistic. The first incarnation of the Washington Senators had fled town and become the MInnesota Twins only a decade earlier. MLB, wanting to prevent members of Congress from getting riled up enough to repeal baseball's antitrust exemption, had put a new franchise in the Nation's Capital immediately.

But Short's trade with Detroit, combined with Senators' expiring lease at RFK Stadium, fans headed into the 1971 season sensing that the end of baseball in the Nation’s Capital was once again upon them. Publicly, Short acted like he was a victim of a bad deal and hinted that he had even enlisted President Richard Nixon to help him work out a better lease, since the stadium sat on federally owned land. (Nixon was indeed a baseball fan, and even brought his family to a meaningless late-season Brewers-Senators game that year where only 3,884 other folks showed up.)

Behind the scenes, however, Short was lobbying baseball's powers that be to let him leave for Arlington, Texas, where the mayor was wooing the Senators owner with promises of the most lucrative broadcasting deal in baseball and other assorted riches. Sports Illustrated wrote in August 1971 that Short's attempts to negotiate a new lease on the stadium were phony and that the owner was actually just "looking for the quickest way out of town. "

In his memoir, former MLB commissioner Bowie Kuhn recalled a phone rant from Short that he had to endure during the 1971 season: “No one can keep me in Washington, not Nixon, not Cronin, not Kuhn!” Short railed.

Short ended up being right. Nobody could stop him. In early September, Short announced that that he was indeed taking the Senators to a different city. Rage in the fan base that had built during the team's last month in D.C. all came out on Sept. 30, 1971, when Washington played the New York Yankees in the last game of the season. Povich wrote that everybody who showed up for the goodbye game was united in "reviling club owner Bob Short for shanghaing the team to Texas." Among the biggest cheers of the night came when a massive banner was unfurled from the upper deck in left field: "SHORT STINKS."

In the eighth inning, the crowd began chanting, "We want Bob Short!" Among the reviled was Bill Holdforth, a young usher at RFK Stadium. Holdforth became a local hero that night by parading around the stadium near game's end carrying an effigy of his boss, the owner. That display helped push the home fans over the edge. With two outs in the bottom of the ninth and the Senators leading the Yankees, 7-5, a massive mob stormed the field. The interlopers stole the bases and danced on the pitchers mound as players from both teams headed into the clubhouse for safety. Umpires declared the game a forfeit for the Yankees, giving Washington its 96th loss of the season and final defeat ever.

The Washington Senators were dead. The Texas Rangers were born.

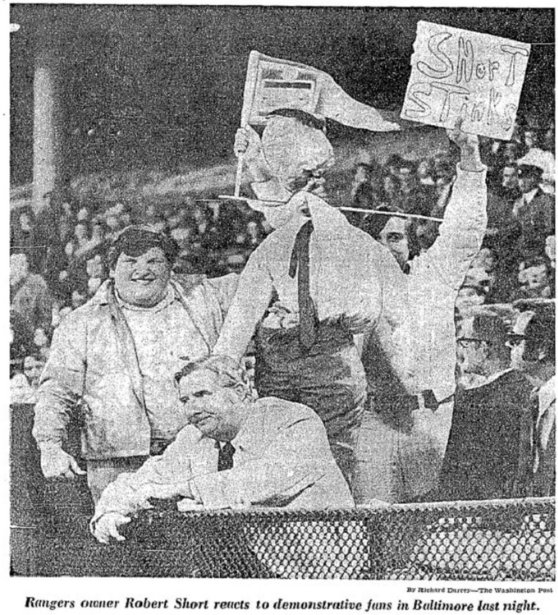

Senators fans weren’t done with Short, however. Holdforth showed up at Memorial Stadium in Baltimore with his Short effigy the following season to heckle the visiting owner during a Rangers-O’s game. A photo of Holdforth taunting Short with the likeness was published in the Washington Post and went over the wires.

Short also reported that somebody poured a beer over his head at the same game, and word around town always held that Holdforth was the guy who'd doused the devil in Baltimore. Holdforth used the notoriety from the Short episodes (as well as fame gained while winning a 1972 citywide beer guzzling contest in which he drank a reported 33 beers, then immediately challenged everybody in the bar to another drinking contest) to launch a bartending career. Holdforth, holding court at mostly Capitol Hill watering holes under the nom du booze Baseball Bill, went on to become the most famous barkeep in D.C. history. Holdforth died in 2017, and I went to a memorial service for him at an American Legion Hall on Capitol Hill. Barflies and baseball fans from all sectors of the city bonded on two points: Bob Short was an ass, and, legend be damned, Baseball Bill was actually not the Senators fan who’d poured a drink over Short’s head at Memorial Stadium back in 1972. They repeated the defense Baseball Bill offered through the years whenever somebody brought up the dousing: “I’d never waste a beer like that!”

Short sold the Rangers for $9.5 million before the 1974 season, after the team posted the worst record in the majors in its first two years in Texas. He tried to take over a group buying the San Francisco Giants, but was tossed out after citing his experience of running two professional sport franchises. Short then tried to return to D.C. in 1978 as an actual senator, mounting a campaign for the U.S. Senate out of Minnesota. A group of fans of the team he took, led by Baseball Bill, put together a poor man’s PAC and bought ads in Minneapolis newspapers railing against Short’s candidacy. He lost.

Short died in Minnesota in 1982. But he’s never been forgotten. D.C. officials helped steal the Montreal Expos from Montreal by promising MLB all sorts of goodies, among them a publicly funded new stadium, and turned them into the Washington Nationals. While the new home was being built, the Nats played at RFK Stadium, the Senators' old haunt. During the final game at RFK on September 2007, fans in the upper deck unfurled a massive banner: “SHORT STILL STINKS.”