In the winter of 2002, researchers from the Monterey Bay Research Institute found a rotting gray whale at the bottom of the bay, more than two miles underwater. The whale's remains were carpeted in an indecipherable meadow of red plumes, which the scientists would discover were new species of worms that fed on the tissues inside whale bones. Even if earthworms had eyes, these worms would have been unrecognizable to any garden-dweller as a fellow worm; the bone worms resembled pinkish palm trees attached to a greenish, pulpy root system. The researchers placed these strange new worms in a new genus: Osedax, Latin for "bone-devouring."

In the years since, scientists found dozens of new Osedax species feeding on whale bones around the world. Many scientists thought Osedax specialized on whale falls, meaning they exclusively fed on the sunken mammals. But whale falls are serendipitous (for the worms; they are rather tragic for the whales) raising the question of how the worms managed to persist for such a long time with such sporadic meals. Then a slew of recent studies found that Osedax was not such a picky eater, and readily feasts on cow bones, fish bones, and even crocodile bones. Now, a new paper published in the Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom reveals that, in a pinch, Osedax worms also feed on shark teeth.

Katrine Worsaae, a zoologist at the University of Copenhagen who has researched bone worms before, said she found the results "not too surprising" given that Osedax has been reported chowing down on many different kinds of bones. Ekin Tilic, a curator and section head of marine invertebrates at Senckenberg Natural History Museum in Frankfurt, Germany, and who was not involved with the new paper, was also unsurprised. "Nevertheless, this is an important finding and the paper beautifully demonstrates and proves how Osedax can utilize a previously unknown food source," Tilic wrote in an email.

Rouse, now a marine biologist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego and an author on the new paper, has wanted to feed teeth to bone worms for years. The first whales appeared about 50 million years ago after the Cretaceous extinction event, meaning that any creature specialized to feed on them must have emerged later. But even before whales, the Cretaceous would have offered a bountifully bony repast: gigantic fish and swimming reptiles like plesiosaurs and mosasaurs. "There were plenty of bones in the sea, and of course there were sharks, and sharks go back way before bony fish," Rouse said.

Sharks have been around for ages; the earliest appeared 450 million years ago. In 2019, a team of researchers from Italy suggested holes in the fossil of a ginsu shark from the Upper Cretaceous could be traces of ancient Osedax worms. Could these worms be as old as sharks? After all, bone worms don't eat the actual bone mineral. They dissolve the bone matrix to feed on the lipids and collagen with the help of symbiotic bacteria. Despite their similarities, teeth are not bones. Bones are living tissue that regenerate throughout a lifetime, whereas teeth have no living tissue. But teeth do contain dentin, a tissue that contains a lot of collagen, which is Osedax's real food source. And sharks, whose mouths are literal conveyor belts of new teeth, are a constant supply of dentin.

In 2008, Rouse attempted to test this theory. He dropped a cage of some mako shark jaws and bones from tuna and swordfish more than 3,000 feet deep into the Monterey Canyon. When he recovered the fishbones, Osedax had successfully wormed its way into the fishbones. But the shark jaws, made of cartilage like the rest of their skeleton, had almost entirely disappeared. "A lot of it had gone, and then all was left was the teeth of the shark," Rouse said. But the teeth had all fallen to the bottom of the cage, where they may have been covered in sediment and out of reach of Osedax.

Rouse got a second chance in 2018. "I heard about a game fishing tournament where people caught thresher sharks, which I'm still appalled and shocked at," Rouse said. At this time, Tilic was working in Rouse's lab in San Diego and remembers how saddened Rouse was by the tournament. Thresher sharks are one of the few shark species that can fling their entire body out of the water, and all three species are vulnerable to extinction.

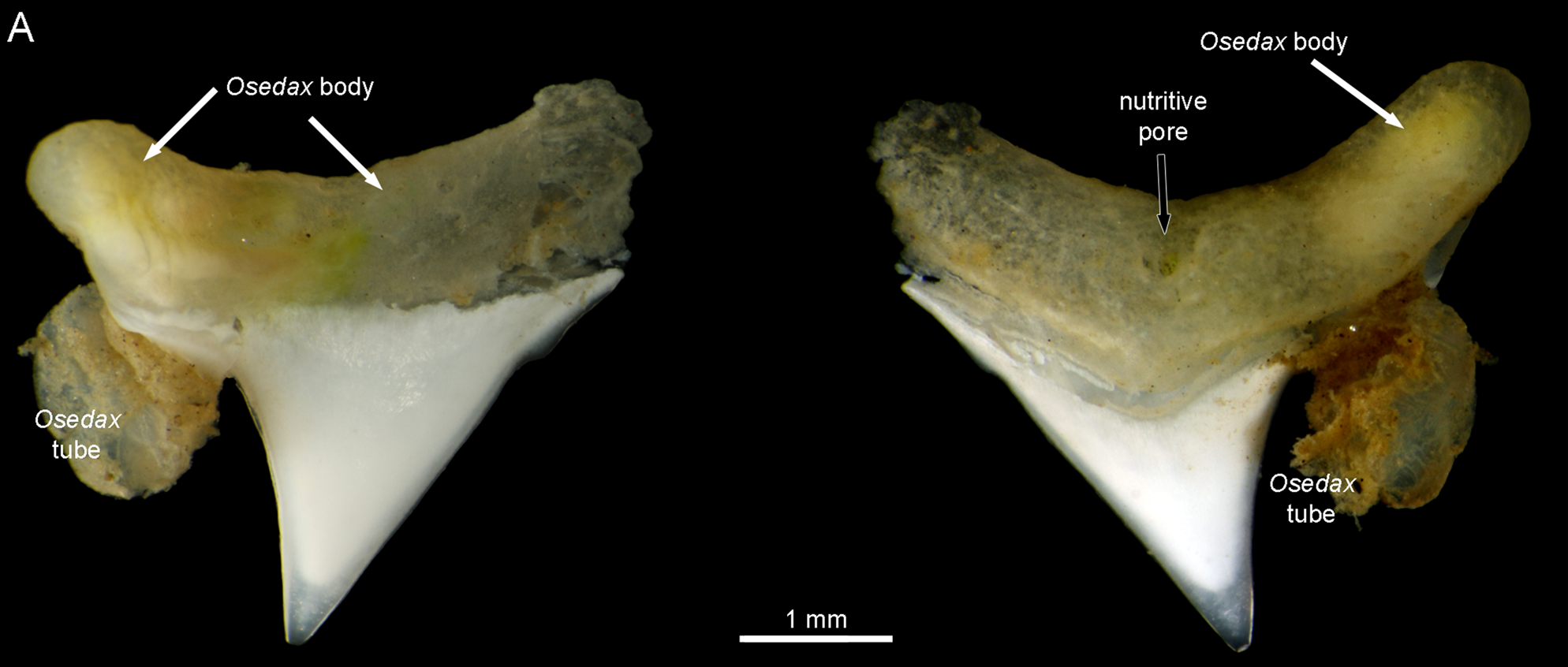

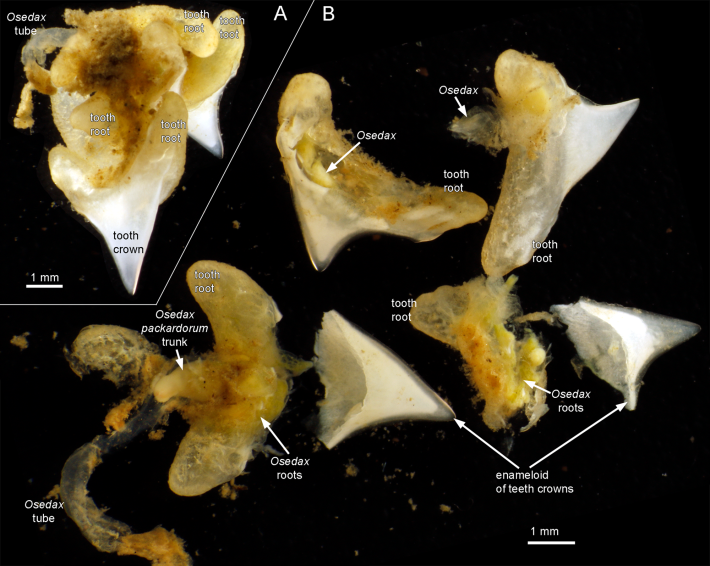

Some of the fishers donated the shark heads to researchers at NOAA, who then gave the heads to Rouse. Shana Goffredi, a biologist at Occidental College and an author on the new paper, took the thresher shark jaws out on a research cruise visiting a whale fall. This time, the researchers put the jaws in a mesh bag to collect every last tooth. Eight months later, Goffredi and colleagues retrieved the bag, which contained the decayed shreds of shark jaws and about 40 teeth, a quarter of which had sprouted mucus tubes—a sign they were breached by Osedax. The worms locate bones as free-swimming larvae. "So they would had to have gone through the mesh one by one to colonize the bone," Rouse said. "It was, wow, one of those great fantastic moments of science when you know immediately it's a really cool discovery," he said.

The researchers sequenced the worms and found two species had colonized the teeth. And these two species, Osedax packardorum and Osedax talkovici, are quite distantly related within their genus, suggesting the ability to feed on dentin could be an ancestral preference. Perhaps, Rouse speculated, the worms initially evolved to feed on cartilage, collagen, and dentin before switching to bone. "These worms are much older than whales, so there must have been another food source for them to live off," Tilic said.

Rouse hopes paleontologists take a closer look at fossilized shark teeth in their collections from the Mesozoic, 252 to 66 million years ago, or even earlier. He wondered aloud: Could shark teeth sprinkled around the seabed have offered Osedax a way of dispersing across the world's oceans? For now, one thing is clear: "These worms are clearly not whale-fall specialists," Tilic said. So stop throwing bread to birds (bad, zero nutrition, even dangerous!) and start throwing handfuls of your teeth (full of dentin, yummy!) to the strangest worms into the ocean. Bone appétit!

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that Greg Rouse was involved with the original discovery of Osedax.