It was Cheer, Netflix's hit documentary series about the Navarro Junior College cheerleading squad, that made Jerry Harris a star. The former Navarro cheerleader interviewed celebrities on the Oscars red carpet for The Ellen DeGeneres Show, chatted with future president Joe Biden on Instagram Live to help him reach young voters, and even met Oprah, who asked him to give her audience some of his legendary "mat talk," when a cheerleader who is not competing—and is thus "off the mat"—screams support and encouragement for their teammates who are.

That Harris, now 22, was one of the breakout stars of the series was hardly surprising to anyone who watched. Season One of the TV show leaned hard on Harris as one of its lead characters. It told the story of him losing his mother to cancer at age 16, of Harris finding himself through cheer, and of his cheer moms raising money for him so he could stay in the sport. All season, viewers were led along to root for Harris to beat the odds and make it onto the mat for Navarro at the national championships in Daytona Beach, Fla. As the rules of sports documentaries have dictated since the Sabol family started filming NFL games in the 1960s, the Daytona Beach results are the Season One finale.

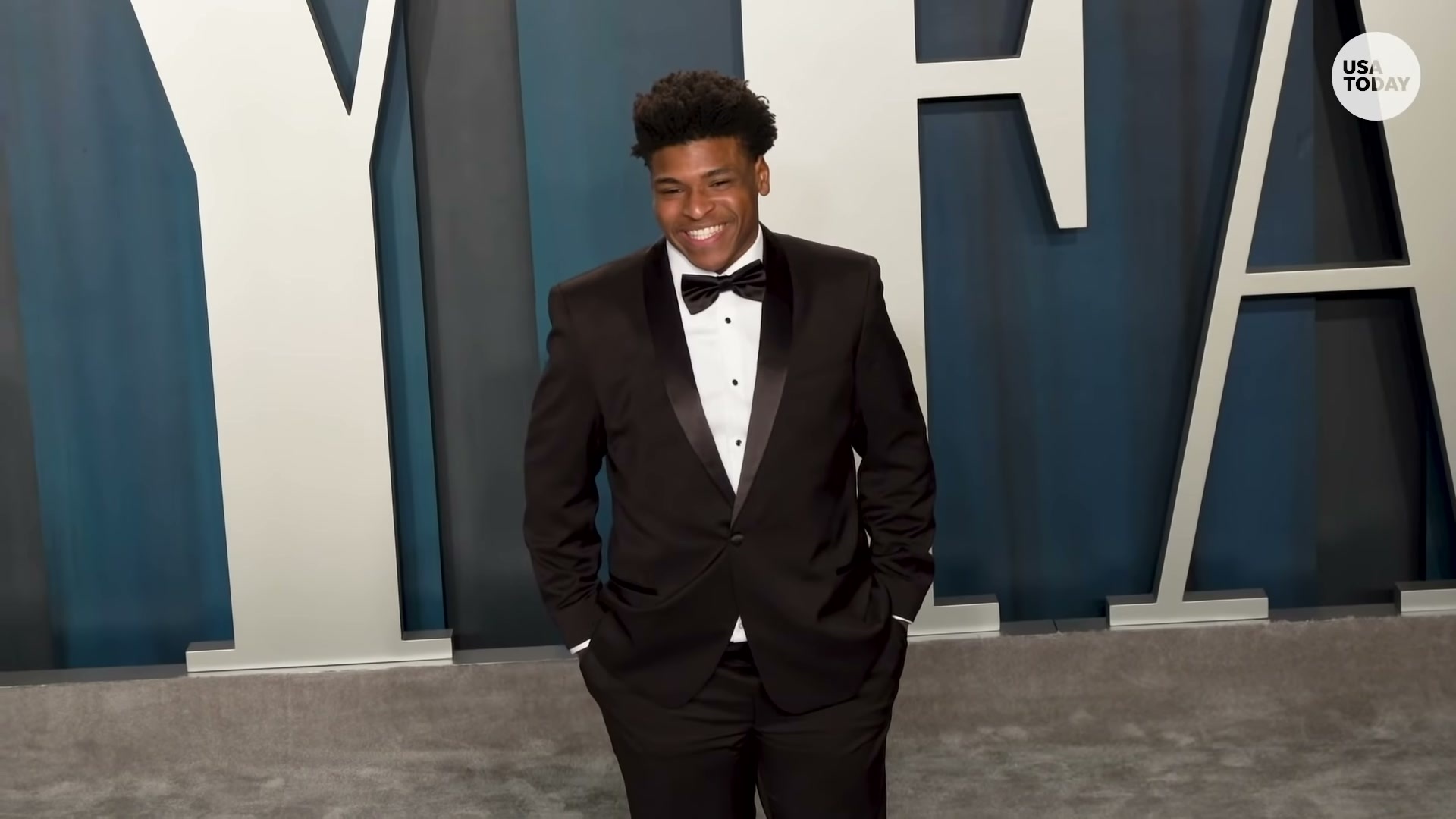

But three months after Harris talked with Biden and eight months after shooting began on Cheer Season Two, USA Today broke the story that the FBI was investigating Harris for soliciting sexually explicit photos and sex from minors. Days after the story broke, a warrant was issued for his arrest, and Harris was charged with producing child pornography. He remains in a federal prison in Chicago while awaiting his criminal trial. He also is being sued in civil court.

The charges against Harris did not stop Cheer Season Two from happening, and Harris does appear a little in the start of the season; he is very busy doing Cameos, so much so that he does them during a guys' trip to get pedicures. Instead, the show chooses to mostly address what happened with a standalone episode about Harris. It's right in the middle of the nine-episode season. The episode does not start out with Harris, though. First it breaks the news that lots of change is happening at Navarro: Cheerleaders Lexi Brumback and Morgan Simianer have left the team. Their head coach, Monica Aldama, also is gone to go chase her dream of performing on Dancing with the Stars. In her place is a new assistant coach, Kailee Peppers. And then comes what the rest of the episode will be about: Harris's arrest.

The episode spends a lot of time with Charlie and Sam, two teenage boys who, like so many people on the TV show, found themselves acceptance and community through cheerleading. (The teens and their mother agreed to appear on camera but asked that only their first name be used, which I am doing here.) They both knew Harris, even before the TV show, because of his spot on the Cheer Athletics Cheetahs—Charlie calls the team their dream team. One day, Charlie said he got a request from Harris via Instagram and they started talking. Harris asked him to send explicit photos.

"I was willing to do that, and was kind of blindsided by his notoriety at the time." Charlie said.

If he didn't respond quickly enough, Charlie said that Harris would get angry. Sam found out after a few months. Charlie then met Harris at a 2019 competition, he said, where Harris begged him to have sex with him in a bathroom. Charlie said no. Some time after, according to Sam, Harris started messaging him too.

The teens did not tell anyone about this. After all, Harris was a star. As Charlie explained: "I wanted to say something about it, but I also felt so ashamed. I was scared that, if I was going to tell my mom, that she would report it. And I knew that, at the time, that if I were to report it, that I would basically lose all my cheer friends—because they all love Jerry or are friends with Jerry."

Their mother, Kristen, found out about this when she was checking one of their phones and saw a message from Harris that looked strange. But even when their mother talked to them about what happened, the boys did not want to report it. As Kristen said, "They didn't want to be the ones who tattled on Jerry Harris because they knew it would be devastating for them socially." It was when Charlie saw the news about Harris speaking with Biden that he told his mother that he wanted to do something.

Doing something about it would prove to be very difficult. Kristen said she called Angela Rogers, co-owner of Cheer Athletics, who seemed skeptical. She reported him to the U.S. All Star Federation, which oversees club cheerleading, yet nothing happened, Kirsten said, so she sent another report to USASF nine weeks later with more details. Again, nothing happened. So, in early August, Kristen said she filed a report with the FBI on a Friday. They got back to her the following Monday.

What followed is all in the public record. Harris was arrested and charged. He also has entered a plea of not guilty. He currently is being held without bail. USA Today went on to do further reporting, and reporters Marisa Kwiatkowski and Tricia L. Nadolny found a long history of cheerleading's overseers mishandling report of sexual misconduct. Investigators would later say Harris's conduct involved more boys than just the twins.

And the boys were right. They did lose cheer friends. They talk in the episode about the cruelty of the community toward them afterward. They said someone quit their gym when they found out what the twins had reported. Charlie described people staring at them and pointing at them in competitions and how it made them feel different and isolated.

"Pretty much all sense of community," Charlie said, "was ripped away from me and Sam."

From there the episode cuts back to the Navarro cheerleaders and how they feel about what happened. Gabi Butler was heartbroken. La'Darius Marshall was pissed. Aldama was depressed. The attorney for the teens, Sarah Klein, herself a survivor of sexual abuse by disgraced USA gymnastics doctor Larry Nassar, tore into Aldama for her weak initial statement on Instagram, a generic call for children to be protected and request for privacy.

And then that's it. The episode ends and, this being Netflix, it rolls within seconds right into another episode. Just like that, Cheer has a new problem: Marshall is quitting the team.

I think a lot about NFL Films while watching Cheer. Just known as "Films," at least when I worked at NFL Media, it's widely believed to be one of the big reasons the NFL went from being, depending on how you measured it, either the third or fourth most popular sport in the United States at the dawn of the 1960s to being the clear No. 1 within a decade. An oft-repeated quote is that Sports Illustrated once dubbed it "perhaps the most effective propaganda organ in the history of corporate America.” (I could not find this quote in SI's online archives. If someone at SI is reading this, please post this article online. Update (Jan. 28, 2022, 5:49 p.m. ET): The quote has been found! I've added a link.)

There are many, many excellent reasons to not worship at the altar of the NFL—the concussions, the many other forms of bodily injury, the extremely short careers of the vast majority of its athletes, the brutal ways players are treated—but good luck remembering that when you're in the middle of an NFL Films presentation. Films realized, early on, the power of Hollywood-style storytelling. You could apply it to anything, even real people, and it works. Here is a hero (good team). Here is a villain (the other team). Watch as our hero does their best to overcome the obstacles (injuries! Bad calls by the referees! Bad luck!) to achieve their goal, which will be reset next week before the next game. All you need is a good storyline, some great camerawork, and a big competition at the end that only one person or team can win.

The best measure of NFL Films' success is the degree to which the sports documentary genre has used its formula, albeit with plenty of personal story about the athletes added on. The Last Dance is Films does Michael Jordan. Formula 1: Drive to Survive is Films does Formula 1. Greg Whiteley, the director behind Cheer, first did another sports series for Netflix about football players in junior colleges, Last Chance U. Per USA Today, at least four members of the 2017 Independence Community College roster, which was featured on Last Chance U, "joined within months of being punished for sexual misconduct at their previous Division I universities." None of those four players were central to the show, but they did appear on it.

What is revolutionary about Cheer is also what is most predictable about Cheer: It is the same product, the same packaging, the same everything, applied to cheerleading. It never could do the story of Harris justice because to do so would require addressing the shortcomings of its own hagiographical storytelling formula. It has to keep going. There has to be another showdown at Daytona. The viewer must be riveted and, by episode nine, the finale, I was. Would Navarro defend its title? Would rival Trinity Valley Community College steal their crown? Everything with Harris was off in the background, another plot point to overcome on the way to ensuring there will be a Season Three about these tightly woven cheer families. There's hugging. There's crying. There's reminders that cheerleading gives.

But I kept thinking about the twins, long after the final credits roll. I remember them saying they were certain they would lose many of their cheer friends the minute they reported Harris. And they did.