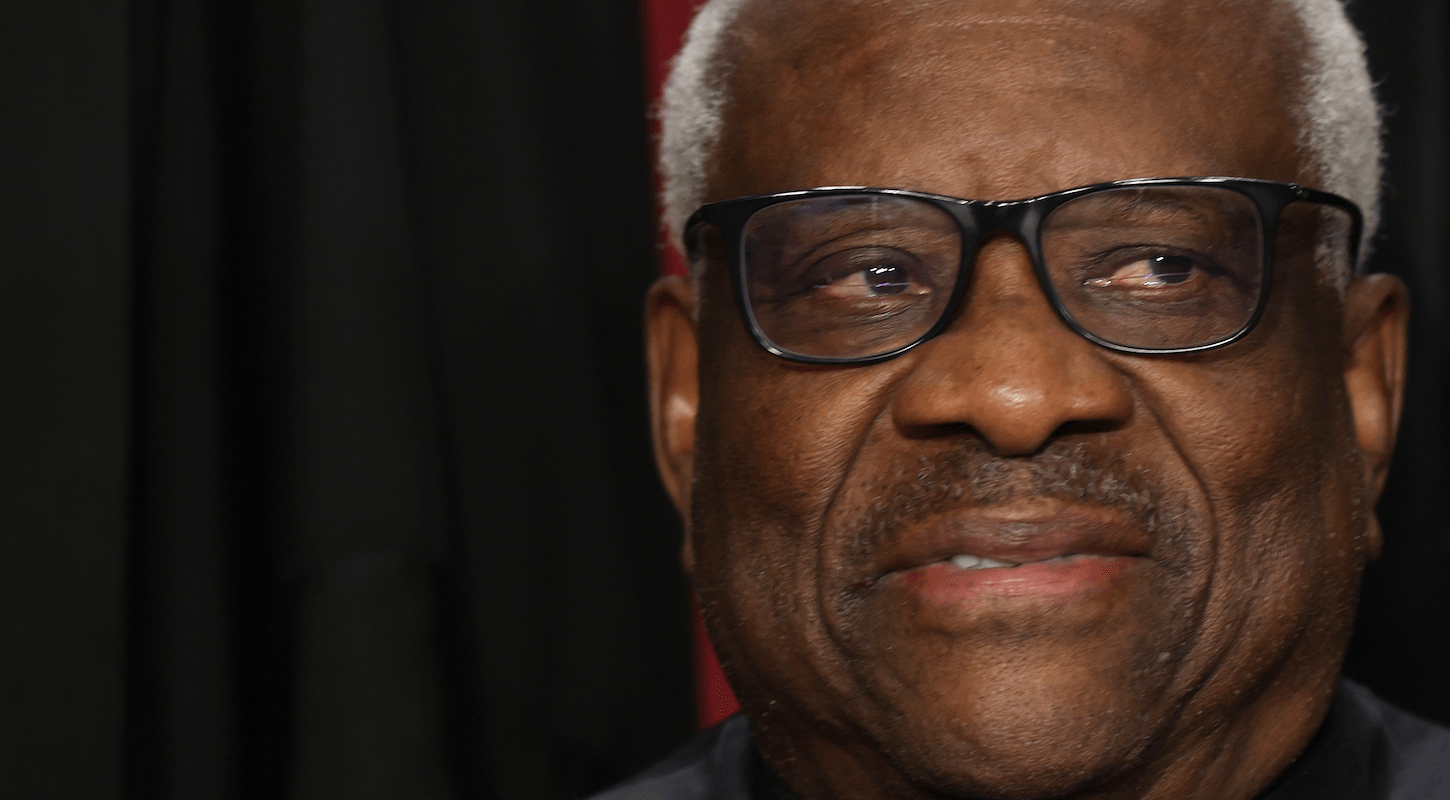

That Clarence Thomas is a big-time piece of crap—brazenly and unapologetically so!—has been general public knowledge virtually as long as the existence of Clarence Thomas has been general public knowledge. Then-President George H.W. Bush nominated him to the Supreme Court in July 1991—this was the first time most Americans had ever heard of him—and Anita Hill's detailed and extensive sexual harassment claims against him went public a couple of months later. His piece-of-crapness thus established, Thomas has since spent 32 years leaning into it, through a court tenure marked by sneering bad faith, regular demonstrations of appalling cruelty, and total indifference to traditional norms of judicial propriety.

So probably nobody familiar with his record will be shocked by the revelation, uncovered by ProPublica in a long investigative piece published this morning, that Thomas has helped himself, over the years, to extravagant gifts from a real estate magnate named Harlan Crow, who also happens to be a "megadonor" to both the Republican Party and the Federalist Society, the conservative legal group that has been instrumental in the right-wing takeover of the judiciary. These undisclosed treats include private jet flights all over the globe, superyacht vacations, and free access to Crow's weird private Adirondack resort with a life-size Hagrid hut(????):

The mountainous area draws billionaires from across the globe. Rooms at a nearby hotel built by the Rockefellers start at $2,250 a night. Crow’s invitation-only resort is even more exclusive. Guests stay for free, enjoying Topridge’s more than 25 fireplaces, three boathouses, clay tennis court and batting cage, along with more eccentric features: a lifesize replica of the Harry Potter character Hagrid’s hut, bronze statues of gnomes and a 1950s-style soda fountain where Crow’s staff fixes milkshakes.

ProPublica

These gifts, which Crow doesn't deny giving but characterizes as totally apolitical acts of hospitality and friendship, certainly seem to amount to a total value of many millions of dollars. Accepting them would be a wild violation of, well ... of the kind of unenforceable ethical norms saps and dupes like to imagine represent effective constraints on the behavior of unelected Law Lords in for-life positions of virtually unchecked power over American society.

Not that I don't appreciate a look into Clarence Thomas's personal ethical dereliction, or into the specific relationship between him and this one right-wing billionaire. It's good to have the venality and corruption of America's rulers laid out in detail; it's an undeniable public good for the networks whereby they enrich themselves and further entrench their rule to be illuminated and mapped for all to see. It's good, in a purifying-rage type of way, for the public to see pictures of Thomas and his psycho QAnon freak wife posing happily with the oligarch bankrolling their lifestyle and his apple-cheeked brood, and Thomas posing proudly in a shirt bearing the logo of Crow's yacht, and the bizarre photorealistic painting of Thomas and Crow enjoying cigars and brown liquor with some lawyer pals in front of a wooden Native American statue carved out of a giant tree stump.

But while all of this may be plain evidence of what used to be termed corruption, everything about Clarence Thomas's entire worldview, as expressed through his jurisprudence and in every other opportunity to voice that worldview he's ever taken, indicates that none of this is exactly hypocritical. Because "rules for thee but not for me" is effectively the sum total of modern conservative jurisprudence, which Thomas has done more than perhaps anyone else to define over the last several decades, and which he is now in a position to enshrine as the law of the land.

So the greatest value of the ProPublica piece, to me, is in the juxtaposition between the stuff it documents—the bald shamelessness, the oddly grubby extravagance, the obvious and total corruption—and a quote like this one, from Virginia Canter, a former government ethics lawyer:

“When a justice’s lifestyle is being subsidized by the rich and famous, it absolutely corrodes public trust ... Quite frankly, it makes my heart sink.”

ProPublica

Or this:

A code of conduct for federal judges below the Supreme Court requires them to avoid even the “appearance of impropriety.” Members of the high court, Chief Justice John Roberts has written, “consult” that code for guidance. The Supreme Court is left almost entirely to police itself.

ProPublica

You could fill a very long book with recent quotes from government ethics experts found in stories about the total obsolescence of their profession. The Code of Conduct for United States Judges and a nickel will get you a cup of coffee at Harlan Crow's Johnny Rockets-for-plutocrats.

Laudably, the ProPublica reporters—Joshua Kaplan, Justin Elliott, and Alex Mierjeski—work to enumerate the places where Thomas may have violated actual disclosure laws, as opposed to vague norms or codes of conduct. What they seem not to have been able to nail down is what actual mechanism there could be for enforcing those laws or penalizing Thomas for having flouted them. Is there one? Is this the sort of thing he could get arrested for? Would he be charged with crimes? By whom? Like, even just on paper, in a version of the world where the rich and powerful faced any real consequences for their malfeasance, what can happen to him because of this?

This is not to criticize the reporting; those questions simply have no real answers. The picture that emerges from their piece is of an unelected and unaccountable body with the effective power to unwrite laws its own members are breaking, and of confirmation to the Supreme Court as lifetime immunity from law and civil consequence. If this is by no means the first time that picture has been painted, this is one of its sharpest renderings. As no small number of observers noted this morning, the often sharply divided court came together in unanimous agreement back in 2016 in its ruling on McDonnell v. United States, narrowing the legal definition of public corruption and hamstringing efforts to hold public officials accountable for accepting bribery. Who could imagine why? And, having imagined why, who could do anything about it?