There was a sense of coronation around these Avalanche, in the usage of that word that implies something expected, even divinely decreed. That clearly, here was the NHL's best team, and raising the Stanley Cup would be a formality for a roster this fast, this stout, this skilled, this deep. That past was prologue, and that their repeated heartbreaks in previous years were not roadblocks but teleological signposts to this moment. This way of thinking is total horseshit.

It doesn't work that way! A team, no matter how talented, does not receive a championship as birthright. None of this is ordained. The better team does not always win a series; the best team only occasionally wins a title. Those are the vagaries of hockey, and the cruelty of chance dictates that most contenders—even many a favorite—never get the parade they may think they deserve. The Colorado Avalanche's Stanley Cup was forged through an NHL-record 72 wins, each one fought for and earned. There was nothing foreseen about this. This was work. They were the best team, but that and a buck will buy you a cup of coffee and a second-round exit. More importantly, they played like they were the best team. That Colorado finally skated up to its potential is the greater accomplishment, worthy of the greatest prize.

It was fitting that the Avs had to take down Tampa, because Colorado was more or less where the Lightning were three years ago—paper favorites, wondering if that's all they'd ever be. Tampa got over its chokes/collapses/bad results from the random number generator/whatever you want to call them against Washington and Columbus, and in hindsight its mini-dynasty looked inevitable. It never was. Players on the Lightning spoke of those disappointments as if they were seasoning, that they had to "learn how to win" before they could get over the hump. I think that's not quite right. I think they had to learn how to lose.

Three straight second-round losses must have had Colorado wondering if that was their ceiling after a drastic rebuild, and each of the three was painful in its own way. A Game 7 loss; a Game 7 OT loss; dropping four straight with a 2-0 lead. The front office could have blown things up, but stayed the course and patched the holes. The players could have been permanently snakebitten, but instead internalized how bad losing feels and how to avoid doing the things that lead to it. "Mentally, we've come a long way from where we've been," said Erik Johnson, the longest-tenured Av. "Sometimes you have to learn from those losses and those defeats. To win, you have to go through some heartache sometimes."

The core was there. Gabriel Landeskog, the aging captain who hasn't lost a step. Nathan MacKinnon, the all-world everything. Mikko Rantanen, his consigliere. Cale Makar, the young anchor nearing the height of his powers. Much of the help they got this year was internal, and a matter of patience: onetime cast-off Valeri Nichushkin and longtime vexation Nazem Kadri took big steps forward, while Andre Burakovsky provided a postseason scoring touch that had been missing. The defensive unit matured, each on their own timeline: Devon Toews emerged as the perfect partner to Makar, while Sam Girard (though injured in the second round) and Bowen Byram showed their NHL caliber.

But it was at the trade deadline that the final puzzle pieces were located by a front office who recognized that you simply don't get that many shots at a Cup, and that a seemingly excellent roster can flame out in the second round as often as not. So why not go for broke? Why not get a postseason hero in Artturi Lehkonen, who would run it back for Colorado? Why not get a veteran presence in Andrew Cogliano, who called a players-only meeting after Game 5 that the Avs to a man said settled them down before this series could go squirrelly? Why not add depth in Josh Manson and Nico Sturm, just in case? (The latter wasn't particularly needed; the former helped steady a blue line especially after Girard's injury.)

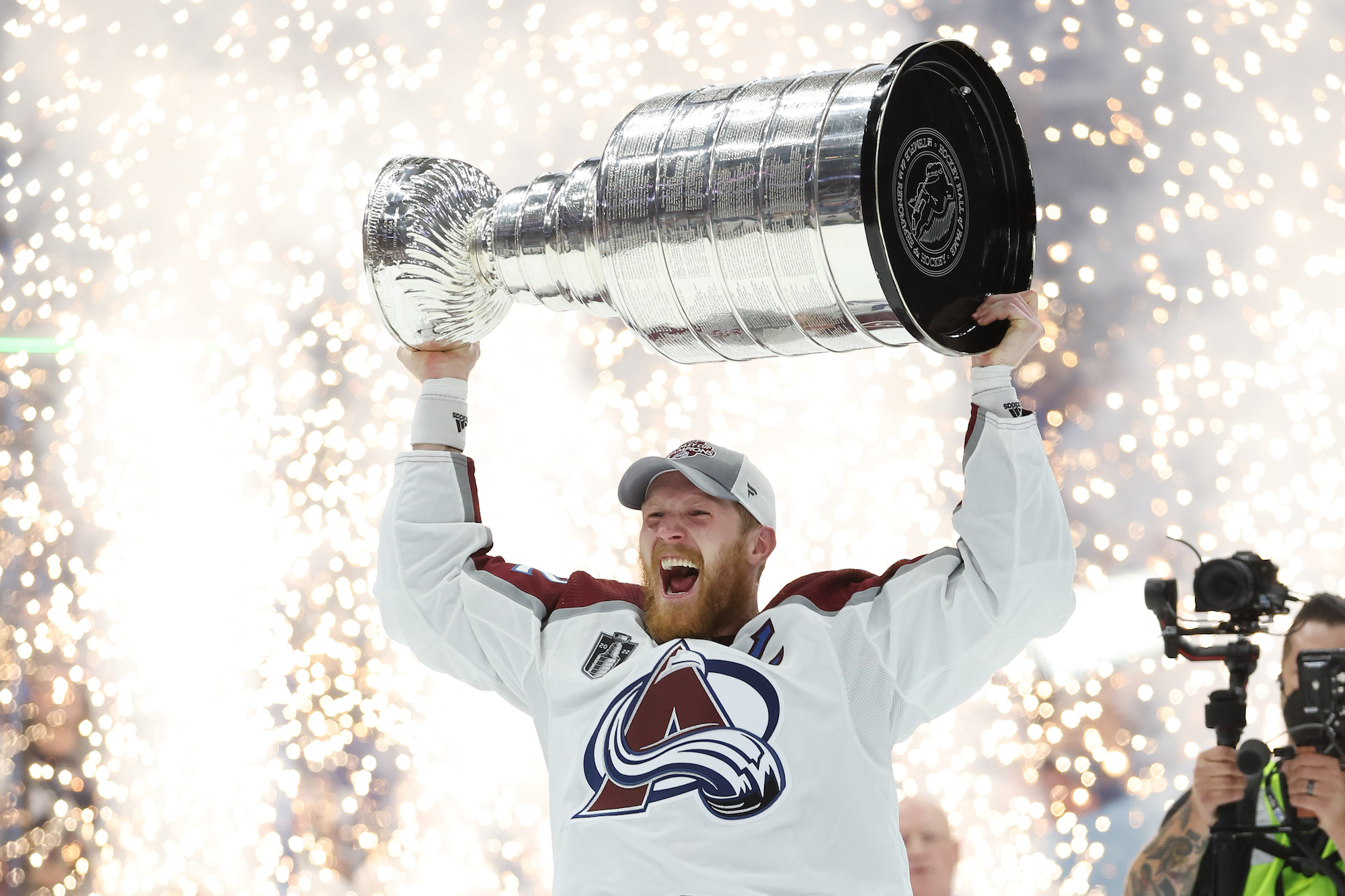

It all came together, as it all tends to do on Cup champs. But survivorship bias alone doesn't explain how the Avs were able to so thoroughly outskate and outwork a Tampa team with all the talent and experience and motivation in the world—a team that knows how to lose and how to win. As gassed as the Lightning may have been after three straight deep postseason runs, and as banged-up as they hinted they were after the game, Colorado controlled the tempo more or less from puck drop to final horn, and if not for a goaltending mismatch in their disfavor, easily could have swept this. This was not one team winning because one team had to lose. This, like the three previous rounds, was the Avalanche never forgetting how to play like the superior team they were, never getting in their own heads about it, and imposing their will upon even the toughest of competition. When this one was over, there was nothing but respect left from the Lightning, who know how hard this is to do.

There's a temptation to treat this as a changing of the guard, as Tampa handing the baton to Colorado as the next great franchise, but I think that's a silly thing to do. Not just because, as Steven Stamkos asked, "Who says we're done?", and not just because as MacKinnon noted, "I might get fat as shit right now, so I don't know if we're going back-to-back," though I strongly suspect that's not going to happen. But because looking ahead does a disservice to what's been achieved and what it took. If the Avalanche are to be the NHL's next Lightning, or Kings or Blackhawks or Penguins, so be it; they'll have to earn it, and good luck to them. But next year can wait for next year, and there is no shame in being the next Blues or Capitals either. Now is all about the culmination of a season and a franchise and of individual careers that just as easily could have ended without this validation etched in silver and been no less eminent for it, but wouldn't have the lasting proof. Greatness is workaday; the Cup is exclusive and forever. Sometimes, the reward for toil is eternity.