Almost exactly one year ago, Congress passed legislation creating a blue-ribbon commission. Officially, it was to be called the Commission on the State of U.S. Olympics and Paralympics. Its mission, a clear reflection of the massive Larry Nassar sexual-abuse scandal, was to gather facts, hold at least one public hearing, and issue a report making recommendations about how to improve the sprawling ecosystem of committees and governing bodies that oversee U.S. Olympic sports. In light of the recent testimony from some of the most famous and decorated gymnasts in U.S. history about how the FBI, as well as many parts of the Olympic apparatus, failed to investigate repeated reports of Nassar's abuse, the commission's work should have been, in theory, treated as more vital than ever.

There's just one problem. The commission has never met, nor done any work, and still cannot—because Congress never budgeted any money for it.

The commission has gone months without activity because it has no money to pay people. Instead of doing what they should be doing—mapping out paths to an Olympic movement where athletes are not abused and feel they can speak up without being punished for it—the commission's co-chairs, professor Dionne Koller, director of the University of Baltimore's Center for Sport and the Law, and Han Xiao, former U.S. national table tennis team member and Pan American Games bronze medalist, have spent months trying get the dollars they need to do the jobs they want to do.

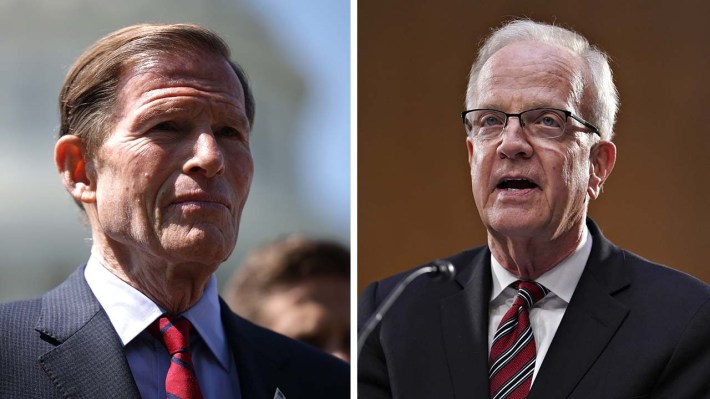

On Monday, Koller and Xiao, who also previously served as chair of the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee's Athletes’ Advisory Council, sent signed letters addressed to Sen. Richard Blumenthal and Sen. Jerry Moran, asking them for help paying for the commission that the Connecticut Democrat and Kansas Republican helped create as members of the Senate Commerce subcommittee that held hearings regarding Nassar. The letter also was sent to Sen. Dick Durbin, Sen. Chuck Grassley, Sen. Patrick Leahy, Sen. Dianne Feinstein, Sen. Lindsey Graham, Sen. Christopher Coons, Sen. John Kennedy, Sen. Maria Cantwell, and Sen. Roger Wicker.

The letter requests that a little more than $2 million be set aside in the 2022 spending plan for this. It also requests an extension of time for the group, giving it 15 months to do its work, as the original deadline, in July, has already passed.

"The Commission we co-chair provides an important opportunity to tackle some tough issues facing the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic movement and to provide specific and informed recommendations to Congress on needed improvements," the letter says. "If we miss this opportunity altogether or if the Commission is unnecessarily limited in the scope or timeframe under which it is permitted to operate, we fear we won’t be able to help solve the real problems that demand attention now, and the credibility of the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic movement will be further eroded. Congress has created a structure through the Commission to do the hard work that is needed to address the areas outlined in the statute and we believe it is important to follow through on that commitment. We are eager to get to work."

Reading the bill that created the group, it's clear that money would be needed and was intended for it. The legislation said that the co-chairs were supposed to appoint an executive director of the commission as well as staff "as appropriate, with compensation." The 16 members themselves hold unpaid positions, but the same proposal said that they would receive travel expenses. None of this can happen without money. And, right now, the commission has no money. People who have been willing to volunteer their time still can't do a thing.

By the time the commission was signed into creation, there already had been indications that Congress did not really want to know everything about how Olympic sports are run.

An early draft of the legislation from the Senate included tasking the commission with "an assessment of whether the United States Center for Safe Sport effectively handles reported cases of bullying, hazing, harassment, and sexual assault." By the time the proposal passed the Senate, that had been removed. Since it became the preferred solution to abuse in Olympic sports, SafeSport has remained underfunded, financially reliant on the same U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee it claims to be independent from, at times been unable to enforce its bans on coaches, had its servers hacked, been called a "joke" by fencers who asked it to investigate multiple reports of sexual misconduct by one athlete who was allowed to travel to Tokyo, and had another suspension reduced by an arbitrator, nearly allowing a twice-suspended volleyball player to compete in the Olympics (He did not, due to a positive test for COVID-19).

And there's the commission's makeup itself. Several are former athletes whose presence makes sense for a body tasked with making sports safer. They include former Olympians Jordyn Wieber and Edwin Moses and former Paralympians Karin Korb and Patty Cisneros Prevo. But there's also former USOPC president William Hybl, who was warned about sexual abuse in gymnastics in 1999 and was accused in one deposition of being present for a conversation about it with other Olympic leaders. (Hybl resigned after the Salt Lake City bid scandal.)

Also on the commission is Rob Mullens, athletic director of the University of Oregon, an institution so intertwined with the shoe giant and athlete sponsor that it's been dubbed the University of Nike. Within recent years, Nike has had female employees speak out about the "boys' club" culture that drove them away and and faced public outcry when people learned it had sponsorship contracts that punished athletes for being pregnant. The president of Purdue University, former Indiana Gov. Mitch Daniels, also is on the commission, a seeming nod to the the fact that the NCAA as well as USA Gymnastics are based in Indianapolis.

But it's one thing to create an imperfect commission. It's another thing to prevent it from even meeting.

By now, Congress has held many hearings to discuss sexual abuse within the Olympic movement. They have been broadcast on TV, streamed online, and generated plenty of press coverage for the politicians involved. Moran and Blumenthal even wrote a piece in 2019 published in USA Today headlined: "We investigated Nassar abuse of gymnasts. Here's how to make sure it never happens again." Now there are 16 people ready to continue Moran and Blumenthal's work, to take those words and change them from op-ed soundbites like "athletes and accountability first" or "transparency and accountability" and turn them into concrete policies and positions. But it's that next step, moving past using sexual abuse in sports as a talking point and actually taking meaningful action to stop it, that seems to elude leadership time and time again.