Ryan Feldman was holding an IV bag when it happened. Something ripped when he pulled the line out and almost an entire bag, with 950 micrograms of liquid inside, spilled and doused his hand in fentanyl. “I was a little annoyed at first,” Feldman told me. “But then I realized: Sometimes in science an accident is an opportunity.” Basically, Feldman realized he had an experiment on his hands—literally.

Feldman had seen the spate of stories in the news about police officers (and other emergency personnel) who have allegedly overdosed after merely touching fentanyl. The drug is an opiate, about 50 times stronger than heroin, and has largely replaced heroin and other opiates in the recreational drug supply in the United States. This has led in part to a massive rise in overdoses despite the relatively wide availability, under the brand name Narcan, of naloxone, a drug that can reverse an overdose.

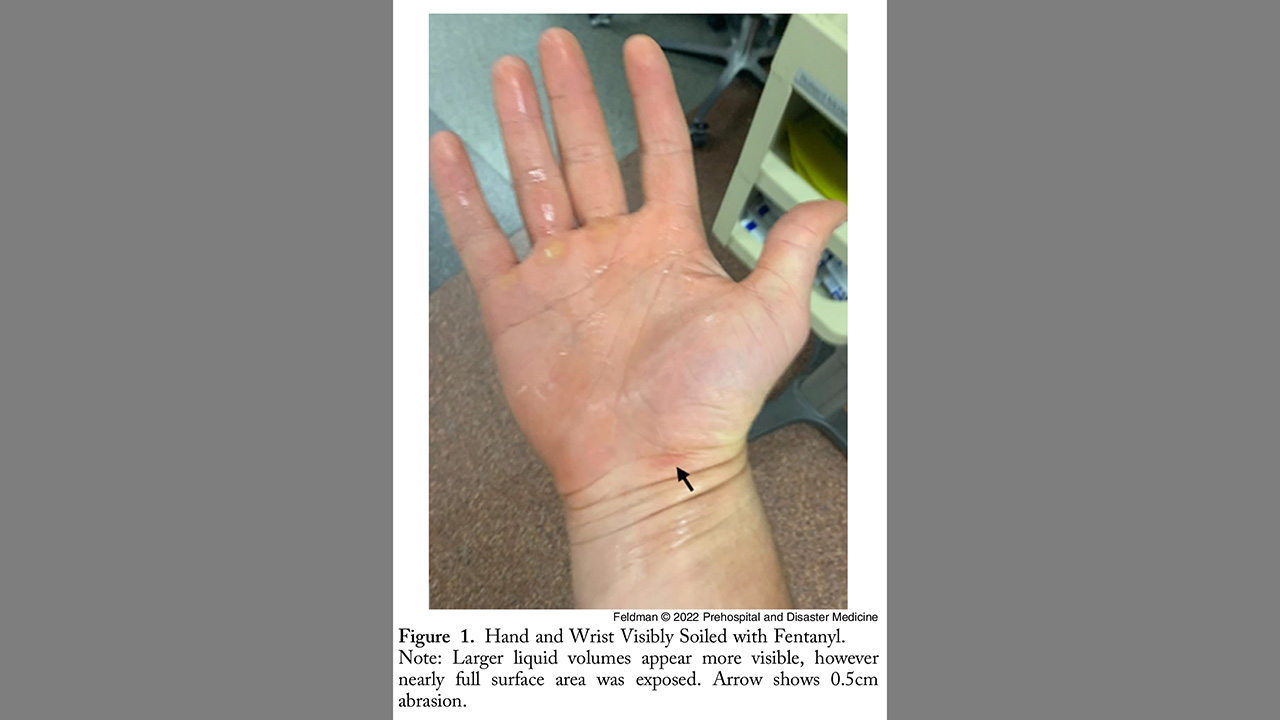

As a toxicologist, Feldman would also have been able to see the glaring problem with all those stories of police officers suffering dermal fentanyl overdoses, which is that such a thing is basically impossible. Fentanyl is skin soluble—but not at a rate that would cause an overdose. And so Feldman was abruptly the subject of a nice little experiment: His ungloved hand was doused in fentanyl, after all, and he even had a cut on his palm, allowing the spilled fentanyl easier access to his body. It was about a minute before he washed his hands with soap and water.

Feldman did not overdose. He did not even suffer any ill effects. His paper with Benjamin Weston, “Accidental Occupational Exposure to a Large Volume of Liquid Fentanyl on a Compromised Skin Barrier with No Resultant Effect” was published last week. “If there's an exposure that happens to be on your skin,” Feldman says, “you have time to wash it off.”

I was interested in this paper because of how clever I found it: Feldman turned an accident at work into an academic paper. But I was also interested in it because, despite a growing and relatively large push by doctors and scientists and even journalists, police continue to experience ”overdoses” after touching fentanyl—sometimes even just after being near it. Because fentanyl is everywhere, these stories are everywhere, too, and reported just as credulously as they were before people started pointing out that there was effectively no way that any of this could actually happen.

The toxicologists I’ve talked to have basically settled on what’s happening here, and it's the same conclusion that my own experience with drugs pointed to: Cops are having panic attacks upon encountering fentanyl because they believe they are overdosing. The symptoms seem to never match up with those of an actual opiate overdose. For one thing, these reports of overdoses never include the officer reporting a wave of euphoria before collapsing (there’s a reason people use opiates). Reports often do not include the blue lips and fingernails, the limp body, and the reduced heart rate consistent with opiate overdoses. It’s pretty clear that police, sometimes other emergency personnel, are simply suffering panic attacks—quite possibly because they, like everyone else, had heard all those previous stories about these kinds of impossible overdoses.

Most of the recreational drug supply in the country is unregulated. So maybe police are encountering a different fentanyl analogue—such as carfentanil, a formulation that is more potent than fentanyl. There are very few examples of dermal carfentanil exposures, as it happens, but Feldman did some modeling. The paper explains:

To cite an extreme example for illustrative purposes, calculations from in vitro modeling with carfentanil (more lipophilic) at extremes of exposure (“infinite” dose model providing continued absorptive gradient, and using maximum observed flux rates) demonstrated the drug would need two minutes of exposure to the full palmar hand surface area of each hand to absorb a biologically relevant dose and up to 44 minutes to absorb a lethal dose.

In summary: You would have to keep your skin submerged in carfentanil for three quarters of an hour before dying.

I wrote a long story last year about this rash of not-overdoses, after San Diego sheriffs released a video that showed an officer allegedly overdosing. The media reported this story so widely that there was actually a lot of pushback. Ryan Marino, a doctor and toxicologist who spends a lot of time tweeting about drug misinformation, helped organize an open letter from “a concerned group of health professionals, first responders, public health researchers, drug journalists, and people with lived experience.” (I agree with the statement but did not sign this. I consider myself primarily a t-shirt designer.)

Stories of cop fentanyl “overdoses” have been spreading since around 2016, when the Drug Enforcement Administration released a report about dermal fentanyl ODs. The falsehood that you could overdose by touching fentanyl spread widely among police departments. In a study last year, about eighty percent of officers surveyed believed in dermal insta-overdose. The San Diego sheriff’s video was a soft-focus, professionally produced video that went wide. But so did retractions. Not everyone is hyperconnected, and not everyone saw these. But I was hoping that the pushback might be a turning point.

Ah. Last month KCTV, a Missouri TV station, aired a report that was headlined “I knew I was dying’: How 5 rounds of Narcan possibly saved KCK police officer’s life” online. The story was shared widely and instantly debunked, especially in the comments on a tweet by KCTV reporter Angie Ricono. The video appears to show a panic attack. The officer shows no signs of fentanyl overdose. Ricono was harangued about it on Twitter for days. That probably stunk! To her credit, she went back and checked her reporting: “The officer’s medical records show he was treated for fentanyl exposure. There’s no mention of a panic attack.” This is accurate! He was treated for fentanyl exposure. But that doesn’t mean he really overdosed. He was simply treated for one despite the fact that he had a panic attack.

This is not the only fentanyl misinformation spreading in the media recently. A report from Fox 10 in Mobile, Alabama detailed another danger: A child found a dollar on the ground. His parents got scared. Police say the dollar bill contained fentanyl.

“I’ve seen on Facebook. Stuff’s been put on that. Be careful of dollars that’s laced with fentanyl and stuff like that, but I never thought I’d be…I never thought I’d see it,” said Jake.

The Turners immediately went to security, who called the police. A field test was done to confirm the powder was fentanyl. After the family was observed for a while, they were able to leave. Orange Beach Police said that while fentanyl-laced money has been showing up more around the country, this is the first case they’ve seen.

“I can’t say it’s becoming a national concern, but I can say, if it is and we have visitors from all over the country in our area, to please be careful. If you see money folded up on the ground and it doesn’t look normal, don’t pick it up. Leave it alone. If you suspect anything suspicious, please call your local law enforcement,” explained Lt. Trent Johnson with Orange Beach Police.

My framing of this story would be a bit different: The police stole a dollar from a toddler because people got scared of something they saw on Facebook. It reminds me of an urban legend when I was a kid about people placing needles on movie theater seats filled with HIV-positive blood alongside a note that said something like, “Welcome to the world of AIDS.” These stories still spread, about needles on gas pump handles or other places; just because something is stupid and fake doesn't mean it's going to go out of circulation.

The fentanyl-dollar bill story offers a grim update on the classic urban legend because police officers around the country are sharing it. Perry County, Tennessee sheriffs said there were three such incidents (one was a $10 bill instead of a dollar). “I personally plan to push for legislation for a bill that would intensify the punishment, if someone is caught using money as a carrying pouch for such poison,” the sheriff wrote on Facebook.

And, honestly, why didn’t the whole family overdose? They were all near fentanyl!

Marino, the toxicologist, remains frustrated. “I don't know why these stories won't go away,” he says. “I also had the same kind of hope when that San Diego sheriff event backlash happened, and how it was picked up even internationally by very large outlets. I thought maybe somebody would pay attention, or remember.”

He has even attempted to publish a negative case report, but it keeps getting rejected. Marino told Defector it was a law enforcement officer who had reported overdosing on fentanyl. A hospital ran tests using gas chromatography, mass spectroscopy, and urine testing. It showed no fentanyl present in the officer’s system. “Nobody wants to publish a negative case report,” Marino says.

When exposed to a little bit of information, these stories wilt like an officer who has touched fentanyl. The stories seem to continue, though. Alex Pareene, a journalist, investigated into the Kansas City story for his email newsletter. (I appeared on his podcast last year to talk about my fentanyl story.) He called up the station. His conversation with the news director, recollected:

“We were telling the story of the person it happened to,” she said.

“Well,” I asked, “what do you do when people with expertise tell you what a person says happened to them is impossible?”

“People who weren’t there, you mean?” she responded.

The news director then hung up on Pareene. He hasn’t heard from them again. KCTV will not be changing their report.

There is a way journalism is practiced in the United States that leads to incidents like this, I think. Police essentially operate as an assigning desk for media outlets, especially local news. The cops report something; journalists repeat it. Journalists trust the cops, even in the face of conflicting reports, because that’s how things work. More than that, journalists need cops, who can be very useful sources. Cops have a lot of information, and they will give it to you. But they also have an agenda, like any source. The news treats them as unbiased third-party observers. Just the facts, ma’am. The end result of this is CBSNews.com warning people not to pick money up off the ground because it could lead to an overdose.

On its own, the news media is not going to convince people that dermal fentanyl overdoses are basically impossible. But until cops are taught differently—and there is some hope in that area, as even an online training changed some officers’ minds—this kind of thing will keep happening. You can expect to continue to hear about it when it does.