Welcome back to Cold Comforts, a recurring column in which Soraya Roberts writes about the grim, harrowing, and downright bizarre movies and television shows that she nevertheless can’t stop watching, over and over again.

Dear Zachary: A Letter to a Son About His Father sounds like the kind of movie I would never want to see, which is why it took me so long to actually see it. Based on the title alone, it sounds like one of those saccharine documentaries that only the filmmaker and the subject would ever really care about. One of those forgettable pieces of solipsistic pseudo-art that is essentially just a scrapbook that was released to the public and then everyone just said it was good because no one wanted to hurt anyone’s feelings.

This is not that kind of movie.

This movie is the kind of nightmare no one could dream up. Wait, that’s not true, Sophocles came up with it when he wrote Oedipus Rex about a king who unwittingly fulfills a prophecy that foretold he would kill his father and marry his mother, and then pokes out his own eyes because he’s in despair and you can’t outrun destiny. Except this story is worse. And not just because it’s real.

Dear Zachary is as devastating as it is because it unravels the way bad things unravel in real life. You are born, you grow up, you make friends, you get a job, a partner, a house, maybe a car, maybe a kid, maybe more. You live your life, you create an entire universe around you, you trundle along, and then … FUCK. Bad things tend not to announce themselves, they just kind of land right on your head. Except, OK, sometimes not. Sometimes, if you are paying attention—close attention—you can see it coming, even if only barely. The tragedy here is that even if you do see it coming, that still doesn’t mean you can stop it.

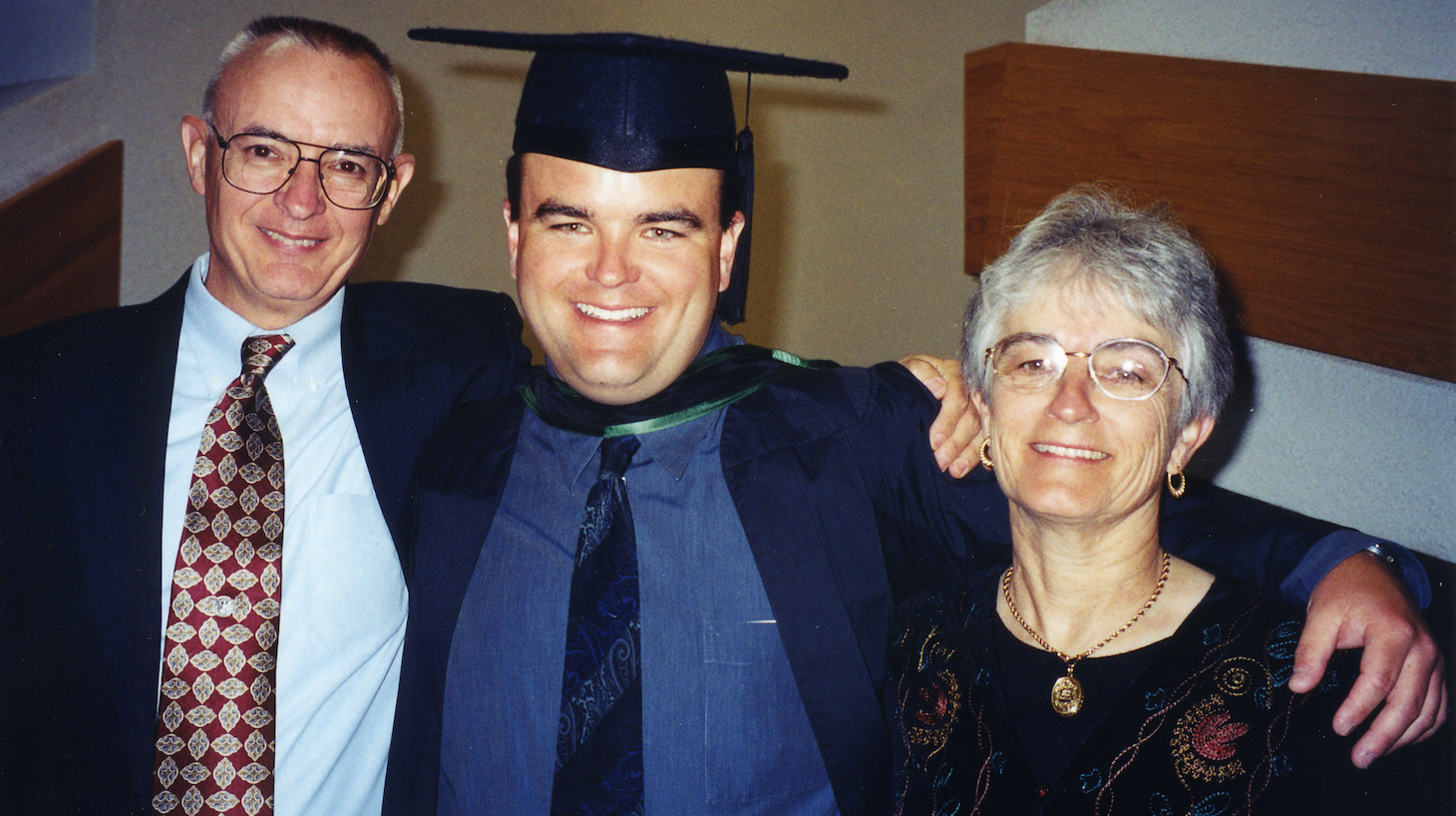

This documentary starts out like a love letter. It opens with a gushing montage of the friends of a doctor named Andrew Bagby, none of whom have one real bad word about him. No less than seven of those friends had asked Bagby to be the best man at their weddings. At one point, one friend says that if he had one tenth of the people who cared about him half as much as they do about Bagby, he would be happy. Then, suddenly, tears. The upbeat music stops and a little boy who speaks in that lispy slow muckle-mouthed way little boys do, asks, “Why did Andrew get killed?”

And this is where director Kurt Kuenne is really smart. He could’ve introduced his friend’s death any way he wanted, and he went with this, with a kid who can barely pronounce the word “killed” asking why one of daddy’s friends has ended up that way. This is the attention thing I was talking about. Because this is foreshadowing. Also foreshadowing is how long it takes Andrew’s parents, Kate and David, to wade through various levels of bureaucracy to confirm his death. Remember these two things as I go on. They are prophecies.

Dr. Andrew Bagby was killed on November 5, 2001, by an older woman named Shirley Jane Turner, who he had dated at a low point in his life. None of his friends liked Turner because she was often inappropriate and even harassed one of Bagby’s exes and just generally appeared to be an incredibly unstable, crude, and unlikeable person—basically Bagby's exact opposite. Turner shot Bagby two days after he broke up with her at a Pennsylvania airport as she was set to fly back to Iowa. After arriving home, she drove 900 miles back to Pennsylvania to kill the man who rejected her. I can say it like that because even without a trial, the evidence was so damning we might as well have been next to her when she carried out the crime. Bagby, that man about whom no one had a bad word, was left lying face down in a Pennsylvania state park with five bullets in him.

“Well, you don’t have to look far,” said Dr. T. Clark Simpson, who worked with Bagby. They were good friends; it was he who Bagby had told about the fatal meeting with Turner beforehand. Simpson advised his friend to call the cops and to not under any circumstances meet Shirley Jane Turner alone. When Bagby said he was going to anyway, Simpson asked him to come to his house right after. This is the first example in this story of someone seeing something bad coming but not being able to stop it. This is not the worst instance in this story of someone seeing something bad coming but not being able to stop it.

It turns out Shirley Jane Turner is pregnant. Which is to say, the woman who killed Dr. Andrew Bagby is pregnant with Dr. Andrew Bagby’s baby. If you didn’t realize the importance of that, Kuenne mutes the film to let you process it. Imagine it. Imagine being the parents of a man who was killed and then having to ingratiate yourself to the killer in order to keep your grandchild safe. What kind of headfuck must that be? How the fuck do you live like that?

If you were waiting to find out where exactly the comfort was in this litany of suffering, it is in Bagby’s parents. If you were to dream up the perfect set of parents, it would be Kate and David Bagby. This is the kind of couple, themselves beloved by hundreds, that produces the kind of son who is beloved by hundreds. I don’t know how else to say it except they are grown-ups: they are funny, but serious; playful, but organized. They are warm. They are selfless. They are simply good people. They are the opposite of Shirley Jane Turner. And the comfort they personify can be found in the fact that even in the face of Shirley Jane Turner, they not only continue, they remain good while continuing. The Bagbys prove it is possible for a woman to kill your child and for you to forge a civil relationship with that woman in order to protect another. With that kind of goodness, anything is possible. With that kind of goodness, there is no limit to the possibility of transcending all manner of evil. As religious as that may sound, that is a comfort. And thank God. Because this is where you need it.

You know when you see pictures of some of your friends and then pictures of their parents as kids and they look identical? This was the situation with Andrew’s son Zachary. It was like Andrew died and then was reborn for a second chance. As one friend said, “He’s like the blessing Andrew left behind.” It was for Zachary that Andrew’s parents retired, cashed in all their savings and moved from their lifelong home in Pennsylvania to Newfoundland, where Shirley Jane Turner lived. It was for custody of their grandchild who looked exactly like his father that they moved to the city of their son’s killer. This is where the foreshadowed bureaucracy comes back. A huge chunk of the remainder of Dear Zachary is the Canadian justice system treating the Bagbys like common criminals while the actual criminal is given a breathtaking amount of freedom. In that time, it becomes clear that, thankfully, baby Zachary has his father’s penchant for emotional maturity and gravitates not towards his mother, but to his grandmother. In that time, it also becomes clear that Andrew’s fate is in danger of also becoming his son’s. And in that time, the Canadian justice system does nothing.

And so, on August 18, 2003, Shirley Jane Turner kills Zachary.

SCREAMS. Blood red screen. Skewed imagery. This is how Kuenne represents his emotion at hearing the news that the woman who killed his friend had also killed his friend’s son. How else do you represent almost virtually the same crime happening back to back despite the hindsight in between? How do you represent the fact that this 13-month-old’s death was preventable? How do you represent the fact that when you see a crime coming from a mile away you still can’t do anything to stop it? How do you represent anguish of that magnitude without turning it into a Greek tragedy? “How dreadful the knowledge of the truth can be,” wrote Sophocles, “when there’s no help in truth.”

“This is what that fucking bitch didn’t know,” David Bagby fumes towards the end of Dear Zachary. He seems to be talking about the unfathomable grief Shirley Jane Turner left behind. But as someone else says, “Grief is love’s unwillingness to let go.” So Andrew's father could just as easily be talking about love. Because she didn’t know love either. And as tragic as this story is, that is also where its consolation lies: that Shirley Jane Turner destroyed everything around her in an attempt to extinguish the love she was incapable of experiencing herself, and in the end she couldn’t. In the end, she died, but love did not. And in that way this tragedy remains hers and hers alone.