This is the debut of the monthly column The American Friend, written by me, Noah Kulwin, journalist and co-host of the Blowback Podcast. The usual subject of this column will be events and people beyond the borders of the United States. But while the phenomena are foreign, their connections to the American government and powerful U.S. interests will be primary objects of my scrutiny. But for this first column, The American Friend’s lens will be trained on the U.S. itself, and backward in time. It’s about the JFK assassination. Last month, the Biden administration released secret government records related to the assassination. The disclosure was selective and incomplete. But why all the drama about documents closer in age to Helen Keller’s life than the present era? And 59 years after JFK's death in Dallas, what might even be left to learn? What could it have to do with the here and now?

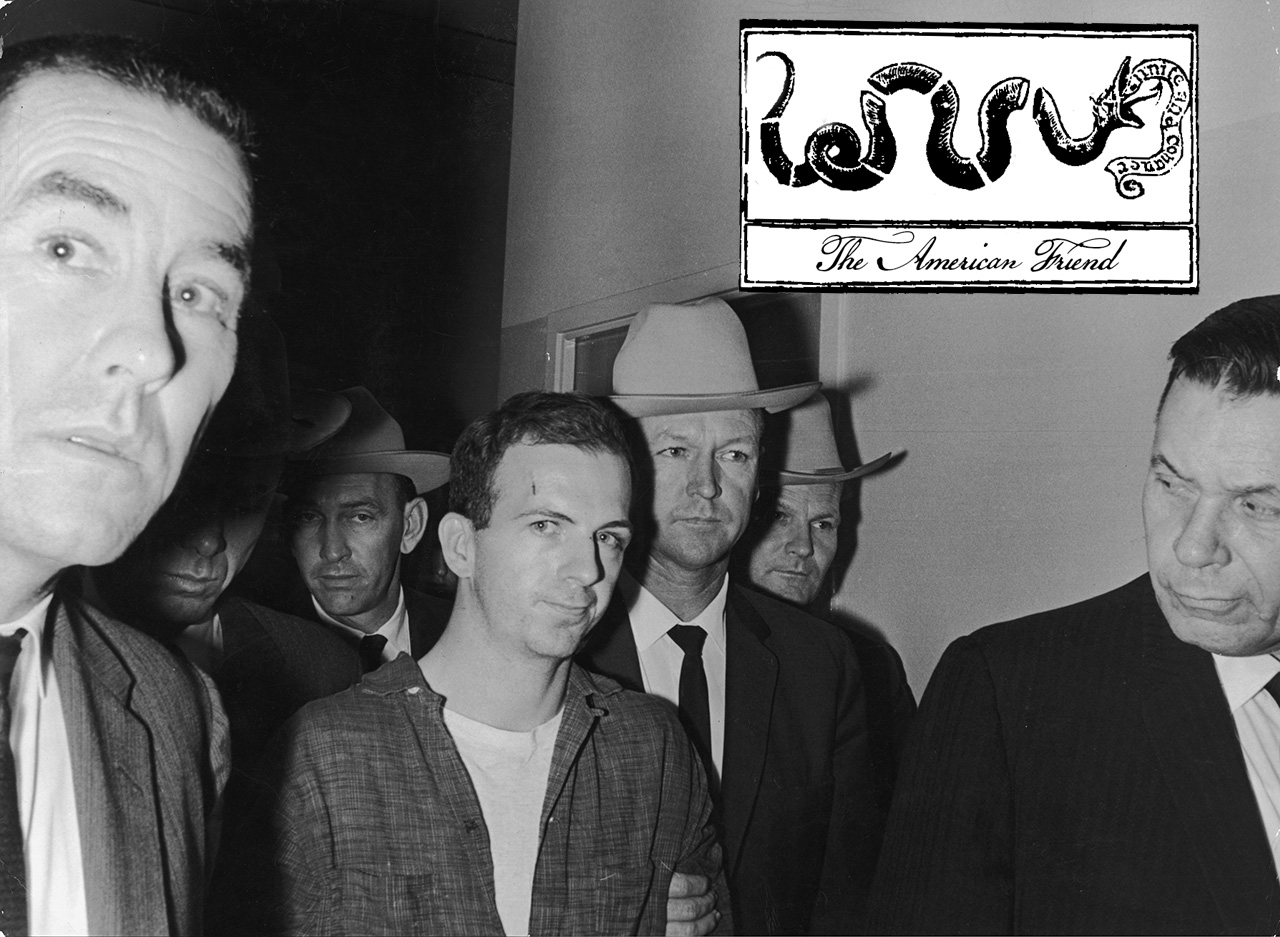

The simplest way to start is at the end. On Nov. 22, 1963, President John F. Kennedy was shot to death while riding in a motorcade in Dallas, Texas. Kennedy was killed by a bullet to the head. Wounded in the attack was Texas Governor John Connally, and dead elsewhere in the city was Dallas cop J.D. Tippit. All three crimes were attributed, after his arrest on the premises of the Texas Theater, to Lee Harvey Oswald.

Oswald is the anchor enigma of the crime because he was shot and killed two days later, Nov. 24, by a local nightclub owner named Jack Ruby. The Warren Commission, convened by President Lyndon Johnson, issued its final report in 1964 and concluded that Oswald had wounded Connally and killed Kennedy and Tippit all by his lonesome. There was no “conspiracy,” left-wing or right, a conclusion that fit prerogatives privately laid out in a Justice Department memo on the same day, Nov. 25, 1963, that JFK himself was laid to rest.

The Warren Commission could only guess at the motives of Oswald, an ex-Marine who defected to the Soviet Union and returned with a Russian wife before moving between Dallas and New Orleans, but the Commission determined that Ruby had impulsively killed Oswald out of affection for the dead president and his living wife. Ruby died in custody, mentally unwell and of cancer, in January 1967. In April 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. was shot while visiting striking sanitation workers in Memphis, Tenn.; a couple months later, Bobby Kennedy, who had served as his brother’s attorney general and had grown something of a liberal conscience in the intervening years, met the same fate in the kitchen of the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, the night of the California Democratic primary, which he had won.

If the assassinations themselves were experienced as shocks—traumas in the literal sense, violent departures from assumed social trajectories connected to the fates of left-of-center heroes—the true cognition shift came with the revelations of the 1970s, as Watergate felled Nixon (1974), the Vietnam War wound down before Saigon ultimately fell (1975), and leaders of the American three-letter secret policing and espionage agencies were shitcanned, swapped out, and hauled before Congress and unfriendly television cameras. Successive government bodies, most notably the Senate’s Church Committee (1975) and the House Select Committee on Assassinations (1976-1978), investigated the sins of the FBI, CIA, the Secret Service, Naval intelligence, organized crime, anti-Castro Cuban exiles, Southern white supremacists, Texas oilmen, state politicians, and Washington politicians.

The HSCA investigation was overseen by G. Robert Blakey, a Justice Department lawyer-turned-academic who in the 1950s developed the “RICO” predicate for racketeering prosecution against the Mafia. With little time and fewer resources, the Select Committee was set up for failure, and while Blakey’s final report endorsed the idea that Lee Harvey Oswald was part of a conspiracy, it declined to draw from the voluminous data made available to the committee to shed a light on who those conspirators might have been.

If you can believe it, everything changed with an Oliver Stone movie. The release of JFK in 1991 prompted Congressional hearings, which begat legislation creating the Assassination Records Review Board (ARRB). That historically underappreciated entity, during its four years of operation from 1994 to 1998, created a kind of sidelong declassification structure, inadvertently giving historians and the wider public a view into mid-century political plate tectonics.

Tens of thousands of records, "3.75 million pages in 1,600 cubic feet" according to one 1997 account, were processed by the ARRB without the onerous trial-and-error, wait-and-see of traditional Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests. Stone’s movie is mentioned in the introduction or acknowledgments of many since-published books about the JFK assassination because of its universally accepted role in creating the ARRB.

The lesson here is that popular interrogation of the historical record really can yield the journalistic equivalent of a jump to hyperspace. Among the revelations to emerge from the ARRB’s files was that the CIA had directly interfered with the integrity of the last investigation into the assassinations of the 1960s. In particular, the Agency had assigned a veteran officer named George Joannides to operate as the conduit between the CIA and the HSCA in the late 1970s. It was a job, as the investigative journalist Jefferson Morley has established, for which Joannides was pulled out of retirement.

Declassified files and subsequent reporting established that in November 1963, Joannides was a case officer supervising anti-Castro Cuban exiles who composed, among other groups, the Directorio Revolucionario Estudiantil (DRE). In fact, known to the Cubans by a pseudonym, Joannides had directed the group, in the hours after JFK was killed, to begin telling journalists what the DRE knew about Lee Harvey Oswald, the president’s accused assassin. That was, as Morley once put it to me, “the first conspiracy theory of the assassination to go public.”

G. Robert Blakey, the uptight lawman/professor who ran the HSCA investigation and oversaw the completion of its final report, took back his decades-long defense of the CIA's integrity after learning the facts about Joannides. Blakey could not trust an agency that would send an officer directly involved in the events being investigated as its buffer to the committee investigating those events. I spent three hours with Blakey on the phone in 2020, when he had retired from academia and was living in Arizona, and he further affirmed and expanded on this point.

To what degree do you feel people today can trust these institutions like national security institutions, the leadership of the military, the CIA, and so on? I think I have confidence in the FBI. For example I knew [ex-FBI director] Louis Freeh, and Freeh was an honest man, and proof that he was an honest man was that he had a problem with the president. Let’s go down the street. Can you trust the CIA? And my answer is no. Now, do I believe that the CIA was involved in the assassination? If you mean, the highest level in the CIA, no. But when you get down to [CIA assassinations guru William] Harvey, and [Chicago Outfit mobster Johnny] Rosselli… I think that was the shooter behind the grassy knoll. I think it was probably some anti-Castro Cubans. And I’ve got some possibilities for that.

Those possibilities are not endless. They are discrete, quantifiable, and human. The official story, put forward by the Warren Commission in 1964 and buttressed by nearly every institutional authority in the years since, has been that Oswald and Ruby were not part of a conspiracy. “JFK’s head just did that” might as well be the Warren Commission line, and it would be only mildly less credible than the “lone gunman” theory and the “magic bullet” theory that together purport to explain the circumstantial and physical qualities of the crime. It is easy to see why, from the 1970s until the 2010s, an outright majority of Americans rejected the Warren Report’s findings and believed that some conspiracy beyond Oswald had killed Kennedy.

This year, for the first time, that majority became a mere plurality, falling to 50 percent, according to a reputable pollster sympathetic to JFK assassination researchers. Rather than vindicating proud defenders of the Warren Report, most notably the journalist Gerald Posner, this survey represents the mighty power of a government narrative that is supported both informally and (as credibly alleged by Alec Baldwin, among others) doctrinally across establishment media. Once held up as a potential antidote to this kind of brute force historical record entrenchment, digital tools have repeatedly proven every bit as capable of reinforcing state control as they are at weakening it. What is to be done, then, is to crash this dialectic and explain the JFK assassination as a historical phenomenon, rather than as mere violation of liberal virtue, or a Red plot, or the outgrowth of various emotional derangements, and thereby give us something useful to say about the here and now.

A helpful way to think about the JFK assassination, and political assassinations more generally, is to be more Dragnet about it than discursive. There are two people with an undeniable connection to the assassination: Lee Harvey Oswald and Jack Ruby. To what world did they belong, and in what ways might they have been connected? We’ll begin with Ruby.

On the morning of the assassination, according to a story later furnished to the IRS by an informant, Ruby spoke on the phone with the informant and asked if he would “like to see the fireworks.” A solid summary of Ruby’s actions can be found in a 1975 Texas Monthly story by the late Gary Cartwright:

...always at the center of the action, passing out sandwiches, giving directions to out-of-town correspondents, acting as unofficial press agent for District Attorney Henry Wade—who, like everyone else on the scene, simply regarded Jack Ruby as part of the furniture. Twice during a press conference Wade mistakenly identified Oswald as a member of the violently anti-Castro Free Cuba Committee. The second time a friendly voice at the back of the room corrected the DA. “No, sir, Mister District Attorney, Oswald was a member of the Fair Play for Cuba Committee.” The voice was Jack Ruby’s. How did he know that? Well, it was in all the news reports, but there is a more intriguing theory: an FBI report overlooked by the Warren Commission suggests that one of Ruby’s many sidelines was the role of bagman for a nonpartisan group of profiteers who stole arms from the U.S. military and ran them for anti-Castro Cubans.

“Bagman” is the right word for Ruby, about whom we now know more. He operated a series of clubs, the last of which was the infamous Carousel Club in downtown Dallas, which opened in 1960.

“Its most important employees were its frequently rotating dancing girls, whom Ruby recruited locally and from clubs all over the country,” the historian David Kaiser writes in 2011’s Road to Dallas. “They belonged to the American Guild of Variety Artists (AGVA), a mob-controlled union which the Senate Rackets Committee had investigated in the summer of 1962.” Despite the ample investigative material in front of them, Dallas FBI agents, according to Kaiser, “made literally no attempt to figure out what happened to the thousands of dollars that the Carousel Club generated every month,” giving up multiple leads that pointed in the direction of, to borrow the parlance of J. Edgar Hoover, “top hoodlums.” The FBI would have known these names well.

Organized crime syndicates in the 1960s were kind of like McDonald’s—a series of geographic fiefdoms and franchises in a business that involved a lot of real estate in far-flung places. After the Cuban Revolution deposed the dictator Fulgencio Batista and took control in 1959, Havana’s mob-controlled hotel and casino nexus was imperiled. The political alignment of the Revolution was still considered potentially U.S.-friendly at that point, and previous patrons and influence peddlers from the Batista era sought to maintain their influence.

Santo Trafficante, a Tampa kingpin who had parlayed his money from boleta lottery rackets into controlling interests in five Cuban casinos and hotels, had (like CIA elements and other mob figures) kicked cash and support to the Cuban revolution as a way of hedging its bets. It didn’t do him any favors when he was detained on the island in 1959. According to a British journalist held at the camp with Trafficante, who gave his story to the CIA in London shortly after the JFK assassination, the gangster was visited multiple times by “another American gangster type named Ruby.” Eighteen days after Ruby arrived in Cuba, Trafficante returned to the United States.

The two other Mob “franchises” relevant here are the Chicago Outfit, which employed Sam Giancana and the LA-based Johnny Rosselli, and the Louisiana-East Texas empire of Carlos Marcello. All of those senior mobsters were partners and investors in a sprawling, diverse and complicated network of businesses across the country. Rosselli, who had a Hollywood blackmail conviction from the 1930s on his record, was tight with labor racketeers and studio chiefs alike; he shut down strikes, became a tabloid fixture, and was widely known to be the Chicago boys’ Los Angeles field man.

Rosselli operated as the mafiosos’ first intermediary with the CIA in the early 1960s, via Howard Hughes’s personal detective Robert Maheu. The Agency wanted to take down Fidel Castro; the Mob had strong motive, on-island connections, both violent and clandestine dispositions, and shared interests with the government in the anticommunist cause. According to the CIA official who authorized the funds for the mob, CIA-manufactured poison pills were slipped to the mafia, to be used in the assassination of Castro; the Beard was supposed to have been dead as the CIA-assembled and CIA-trained anti-Castro Cuban exiles were storming the beaches in the failed April 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion. In a little-known New Year’s Eve interview on Meet the Press at the end of that year, Allen Dulles said obscurely that rather than a “spontaneous uprising” of Cubans against Castro, the Agency had been “anticipating other developments.”

The mafia’s failed assassination plots did not unplug them from the increasingly fetid world of criminal anticommunist enterprise and conspiracy, the “dark quadrant” of American society and economy. In his 2021 book, the historian Jonathan Marshall bestowed that title on what the scholar Peter Dale Scott has termed “deep politics,” former SDS president Carl Oglesby named “clandestinism,” and the celebrated crime journalist Gus Russo called “the Supermob.”

Personally, I like plain old “underworld” as the catchall here, but that’s a matter of word economy and taste. What all these unwieldy titles share is connection to a common and necessarily flawed “overworld” history. Linking the mafia, the CIA, and some anti-Castro Cubans to the killing of a president, in other words, risks becoming a shaggy dog story if it’s not plugged into “the bigger picture.” By that I mean the sort of simultaneously specific and sweeping saga of humanity that would necessarily befit a public political assassination, an overstory that represents the absolute zenith of both extravagantly public and covert ruthlessness.

That bigger picture was the Cold War. The French theorist Paul Virilio correctly described war as a kind of centrifugal force in a society, writing in 1977’s Speed and Politics that “history progresses at the speed of its weapon systems.” As many millions of Europeans learned during the Thirty Years’ War and Napoleonic period, the centralization of authority and allocation of resources required by war gives it the capacity to underwrite the unfurling of the future. Only a general, in that time, could assume the role of “history on horseback,” to borrow Hegel’s famous description of the French dictator and modernizer. A generation later, across the Atlantic, it was the Civil War that essentially gave the U.S. federal government the authority to really rule over the whole country, and the troops to transmit that truth domestically and abroad. America’s next total war mobilization ostensibly lasted from 1941 to 1945.

No longer shackled by wartime rationing and wage restrictions, at the end of World War II, workers staged industrial strikes across the country. Fearful of the threat that movement represented to the evolving “national security” interest, a regime of both wage and price controls was instituted in 1950. Eighteen months later, staring down labor action that would endanger the war effort in Korea, the Truman administration tried and failed to seize the American steel industry. Four years later, the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act created the present-day interstate highway system. NASA-contracted laboratories produced innovations as varied as Velcro and baby formula. Military jet engines using the same propulsion technology as commercial airliners increasingly conveyed people around the world. What we call the internet was initially developed by Pentagon researchers in the 1960s. Adam Driver served in the Marines before he went to Juilliard.

The British historian A.J.P. Taylor once observed that “in every state power rests with the armed forces; and whoever controls these forces controls, in the last resort, the state itself.” Although the Cold War was an amalgamation of proxy wars, deterrence strategies and too many other hijinks to name, it was also a process by which the military fortified its position as the determinant force of the American state. That the Pentagon after World War II became the government’s biggest employer and the globe’s largest capital suck—firing missiles in the long run shrinks the economy rather than growing it—was not preordained. It took a team effort to turn that tragedy into truism.

The relevant dimension of the aforementioned “dark quadrant” in this case concerns General Dynamics (GD), which is today the fifth-largest defense contractor in the world by sales volume. It is, in other words, a purveyor of the very “weapon systems” described by the Frenchman Virilio. At the time of Kennedy’s presidency, the CEO of Texas-based GD was a Jewish businessman from Chicago named Henry Crown. Although he made his initial millions in construction, Crown later branched out, eventually backing the Fontainebleau in Miami, the Waldorf-Astoria in New York, a third of the Hilton hotel chain (founded by his buddy Conrad), and the entirety of the Empire State Building in New York. Crown lived a double life: He was also mobbed up to his shoulders.

“The Chicago owner of the country’s biggest racing wire,” writes Jonathan Marshall, “was murdered by members of the Chicago Outfit in 1946” shortly after talking with the FBI about supposedly “clean” mob associates. The syndicated columnist Drew Pearson reported that these names included Conrad Hilton and his friend Henry Crown. With his associate Sidney Korshak, a notorious Los Angeles mob lawyer and Chicago Outfit fellow traveler, Crown for years steered mob money toward other blue-chip investment opportunities of the Hilton caliber, such as the Madison Square Garden Corporation, Paramount Pictures, and the Desert Inn in Las Vegas. Marshall notes, however, that the main FBI files on Crown have been “purged of such accusations,” and instead identify Crown as “a prominent businessman who is known to the Chicago office and who was a friend of the late Director Hoover.”

Prior to its acquisition of the aerospace company Convair in 1953, which had built tens of thousands of planes in WWII, General Dynamics had been known for submarine production. The economics of the Convair deal were sound enough; submarines were a declining business in the Cold War, whereas the skies were a growth sector, both in defense and commercial contracting. In 1959, Crown closed a merger of his construction business into General Dynamics, making him the military conglomerate’s largest shareholder. The next year, the company ran into serious trouble. Its Convair division “suffered a loss of $425 million on its commercial aircraft programs, the biggest business loss in US history to that time,” according to Marshall. Crown was forced to sell off the Empire State Building—to New York real estate law mogul and fellow mob associate Lawrence A. Wien, naturally—to raise cash.

The 1962 salvation to GD’s Convair woes came in the form of TFX, or the Tactical Experimental Fighter plane. The company’s leadership bet the house on winning the $7 billion contract, then by far the largest in government history. Despite four official evaluations that all concluded a rival bid from Boeing was superior, key allies of Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson intervened to make sure that the politically connected General Dynamics, which had teamed up with the New England-based Grumman, won the bid. Senator Henry “Scoop” Jackson, the favorite Democrat of both Republicans and Boeing, began raising a stink in Congress, and investigations over the course of 1963 turned up strong incriminating links to the Texas political machine that had helped Johnson run the Senate and nab the vice presidency.

“The committee took a close look at US Navy Secretary Fred Korth, a longtime friend and former assistant to Frank Pace, General Dynamics’ CEO,” writes Marshall. “Korth had been president of Continental National Bank of Fort Worth before joining the Pentagon,” loaning $400,000 to Convair and having also “been Johnson’s political manager in Fort Worth.” Marshall adds that Korth “owed his Pentagon job to the vice president.”

What’s more, Johnson “had a reputation for taking free flights from General Dynamics’ partner, Grumman,” which was among the Democratic Party’s biggest corporate fundraisers. Within the Pentagon, as Drew Pearson reported in an explosive column that was supposed to run on Nov. 23, 1963, the TFX had become known as “the LBJ,” and that the threat of Johnson being dropped from the ticket over the matter was quite real. Johnson’s biggest problem was his former protege, an influence peddler and ex-aide named Bobby Baker and nicknamed “Little Lyndon” who, after a late-1950s career peak, found himself in danger of being prosecuted for corruption.

No less than Richard Nixon predicted to newspaper reporters in November 1963 that Kennedy would drop Johnson from the ticket, suspecting that lurid TFX-related tales would come to the fore, involving Johnson, Baker, and Baker’s dinner-and-discreet-sex palace in D.C., the Quorum Club. It was powerful dogma in knowledgeable right-wing circles; when UPI reported in May 1963 about the forced and planned retirements of two generals on the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Congressional sources advised that the duo “took positions in the TFX (tactical, fighter, experimental) which were opposite to [Secretary of Defense Robert] McNamara’s decision” in favor of General Dynamics.

Pro-military media leakers credited TFX with the shitcanning of America’s top generals. The Joint Chiefs’ fight against the White House during the Cuban Missile Crisis the previous fall, in which the military brass lobbied repeatedly for nuclear war, would not become more widely known until years later. But the TFX story and the Bobby Baker scandal were both very much alive in 1963, and potentially valuable political ammunition against the Kennedy administration.

“The Vice President had friends at General Dynamics’ Ft. Worth plant and was anxious to have the contract go to Texas,” Pearson reported in the column filed on the date of Kennedy’s death. “Meanwhile, Jack Rettaliata, vice president of Grumman Aircraft, a co-contractor with GD, was also slapping backs and buying drinks for men of influence. Some of the parties took place at Bobby’s Quorum Club and Rettaliata picked up the tab for at least one private drinking party at the Q club on Sept. 26, 1962.”

The killing of Kennedy and LBJ’s assumption of the Oval Office ensured the death of any investigation into TFX, despite Time magazine’s subsequent insistence that the Republicans had some ground to stand on. Kennedy secretary Evelyn Lincoln, in an account related by Robert Caro, was told by Kennedy four days before his death that his running mate “will not be Lyndon,” specifically citing the brewing Bobby Baker political hurricane.

Outright bribery of Kennedy administration officials was never proven, and Lyndon Johnson’s actual hand in the affair was never fully revealed. TFX was introduced into service years later as the F-111 and was considered to be an expensive boondoggle, something like the F-35 of its time, except perhaps even less functional. A review of the program singled out Roswell Gilpatric, former number two at the Pentagon, for criticism.

Gilpatric had fought for General Dynamics and won, despite having previously been both the company’s and Henry Crown’s attorney. Although Gilpatric wasn’t formally scolded for that until 1970, his ties to General Dynamics were scrutinized in Congressional hearings that took place Nov. 18-19, 1963. Although the F-111 was a failure of a plane, both it and the death of JFK successfully kept General Dynamics and Convair alive. Henry Crown, Marshall notes, would become one of America’s richest men by the 1970s, and the Chicago Outfit’s defense contractor would continue to keep close contacts in Washington:

In the final days of his 1968 presidential campaign, candidate Nixon visited Fort Worth and declared, “The F-111 in a Nixon administration will be made into one of the foundations of our air supremacy.” A year later, President Nixon sat with [Dallas Cowboys owner] Clint Murchison Jr. in plush seats provided by General Dynamics to watch a [Washington/Dallas NFL] game. In January 1972, President Nixon approved the controversial $5.5 billion space shuttle development program, with General Dynamics as a prime subcontractor… At about the same time, Henry Crown handed over a $25,000 contribution to the Committee to Re-Elect the President.”

Political assassinations do not work like black holes, sucking everything beyond an event horizon inside and completely out of view. Organized killings, like all covert operations, leave evidence behind, whether it be personnel, materiel, or money. The question, there, is one of degree.

In the summer of 1962, the head of industrial security at General Dynamics was an ex-FBI agent named I.B. Hale. At that time, Hale’s wife Virginia, who worked at the Texas Employment Commission, arranged for a young man recently returned from the Soviet Union to get work in sheet metal. “Two weeks after I.B.'s wife Virginia got [Lee Harvey] Oswald a job,” summarizes attorney and researcher Bill Simpich, “their sons led a break-in at Judith Campbell's house. Campbell was the girlfriend of not only John F. Kennedy, but also Mafia chieftains Sam Giancana and Johnny Rosselli.”

Campbell’s relationships with those men were known to J. Edgar Hoover, whose FBI maintained a stake-out outside of her home, and an agent wrote down the license plate number of the Hale boys’ car, revealing that it wasn’t just the Hoover FBI that desired blackmail material on JFK. As the FBI man did not observe the boys taking anything out of the apartment with them, writes Simpich, “it is reasonable to assume that they had planted a listening bug,” an argument also advanced by Seymour Hersh in The Dark Side of Camelot.

TFX and the Hales are only one connection between Lee Harvey Oswald and others with motive and means to kill Kennedy. Oswald’s uncle was a New Orleans crook named Dutz Murret who served as a lieutenant to Carlos “The Little Man” Marcello. The 5-foot-tall Sicilian Marcello was born in Tunis and arrived in the U.S. as a child, rising to become the top mafioso in the oil money mecca spanning Dallas, East Texas, and New Orleans. Because of his connections to Oswald and the Agency, that lucrative stretch of Sunbelt turf, and his unclear citizenship status, Marcello cuts a more striking figure than other mobsters, including JFK eskimo brother Sam “Momo” Giancana. For instance, a Marcello associate and pal of Bobby Baker named Nick Popich owned the Lake Pontchartrain property on which anti-Castro Cubans trained in 1963, and which Oswald allegedly visited that year. Another figure on Marcello’s payroll, David Ferrie, a pilot, CIA contractor-and-trainer-of-Cubans, was a one-time Civil Air Patrol compadre of a young Lee Harvey Oswald. Ferrie was memorably portrayed in both Stone’s JFK and Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman; he had a disorder which left him hairless and reliant upon extravagantly tacky fake eyebrows and a wig.

At the time of JFK’s death, Marcello had survived one deportation attempt to Central America by Bobby Kennedy; the Pulitzer Prize-winning crime journalist Ed Reid later credibly reported that Marcello swore an oath of vengeance. That his associates seemingly populated the entire known universe and his motive was strong—and that those of Giancana, Rosselli and Trafficante were as well—led G. Robert Blakey, overseer of the final 1970s House investigation into the assassination, to eventually declare that the Mafia “did it.” The phone calls made by Ruby to New Orleans leading up to the assassination seem, in this light, to be a good indication of where prime operational responsibility likely lay.

But there remains one section left to be filled in. The late Senator Howard Baker said of the CIA during the Watergate scandal that “there are animals crashing around in the forest. I can hear them but I can’t see them.” Carlos Marcello and the Chicago Outfit, and their friends in the defense contracting world, were hardly the only ones with grudges against John F. Kennedy, nor would they have had the means to act against him alone. The training at the Pontchartrain property was publicly exposed by the Kennedys’ mid-1963 turn against the CIA’s anti-Castro Cuban training program, and between the TFX contract, the new post-Crisis retreat in the fight against communism, the Kennedys’ tentative support for civil rights, and the possibility of indictment in a second Kennedy term under newly enhanced prosecution statutes, the Kennedy administration was kicking up a great deal of shit with its ostensible coalition allies despite its continued relative popularity with the public.

By the time Kennedy visited the South in the fall of 1963, credible plots against his life were tracked in Miami and Chicago; the Secret Service still permitted an open-air motorcade, despite an increasingly long and obvious enemies list.

Getting the public to believe that something obviously true is in fact false requires, at minimum, group participation. Although the Johnson White House immediately moved to tamp down suspicion that there had been a Communist plot against JFK, that specific allegation was, in the words of investigative journalist Jefferson Morley, “the first conspiracy theory to reach the public” in the hours after the Nov. 22, 1963 death of the president.

The DRE, the leading CIA-supported Cuban exile group, revealed that it had crossed paths with Oswald in New Orleans that summer; at the time, Oswald was claiming to be pro-Castro, even going out of his way to pick a fight with the DRE members. (After introducing himself one day to the Cuban exiles in New Orleans as a hardcore Castro hater, he reappeared close by passing out pro-Cuba literature on a following day and was confronted on the street by the exiles, a confrontation recorded by both the New Orleans Police Department, who arrested Oswald, and the FBI.) A year earlier, at the height of the Cuban Missile Crisis, DRE leaders falsely alleged in newspapers and on NBC’s Today Show that the Soviets and Cubans were still hiding secret nuclear missiles in underground Cuban caves—explosive charges that Kennedy directly asked to be bottled up at a Crisis meeting with his advisers, lest the DRE (a CIA front group) accidentally unleash armageddon. It had been the DRE’s CIA manager and decorated psychological operations officers George Joannides, according to Morley, who told the group to go out and tell the world what it knew about Oswald immediately after the assassination.

What the DRE thought it knew and what Lyndon Johnson wanted were at odds. The government line, laid out in an internal Justice Department memo shortly after Kennedy’s death, was that Kennedy had been killed by a lone gunman, an aggrieved assassin who was part of neither a left- nor right-wing conspiracy; the Warren Commission made this its conclusion later in 1964. But as J. Edgar Hoover himself noted to Johnson, Oswald had reportedly been part of a bizarre previous escapade at the Cuban consulate in Mexico City, or at least someone who claimed they were Oswald had shown up there as it was evident that at least one Oswald in Mexico was an impersonator. A senior CIA official would later tell Congressional investigators that the CIA’s cameras trained on the consulate had not been working during this time.

Oswald’s connections to the CIA have been historically murky but not totally lost. Antonio Veciana, previously leader of the exile terrorist group Alpha 66, claimed (without corroboration) that in September 1963 he saw his CIA handler, a man known to him as Maurice Bishop (and to the world as David Atlee Phillips), meeting in-person with Oswald. One of Oswald’s known associates in New Orleans during 1963, Guy Banister, was an ex-FBI agent who had contracted with the CIA to handle infiltrations of subversive groups. That Oswald was able to so easily reenter the United States after “defecting” to the Soviet Union, with his Russian wife, and then to receive a loan from the Small Business Administration, are strong indications that people in the U.S. government did not believe Oswald had actually defected.

What has the CIA itself said about Oswald? In 1964, observes journalist Jefferson Morley:

The CIA had “very little information” about the accused assassin, a claim that is no longer credible. In 2022, the CIA has retreated to a narrower claim: that its officers “never engaged Oswald.” The old story that the CIA didn’t know much about him has been jettisoned. We knew all about him, the CIA now tacitly admits. We just didn’t “engage” him. Is the CIA’s new version of the Oswald story factually accurate? Or is it another phase in the “benign cover-up?” That depends on whether you trust the CIA or not.

I first came across the General Dynamics-Convair saga in an unusual place: the first-ever theatrical release produced by HBO, 1984’s Flashpoint. The film, which stars Kris Kristofferson and Treat Williams, is available as of this writing to stream on HBO Max. The film's stars portray two border guards along the Mexico-Texas border who come across a car, a long-dead corpse, a Mannlicher-Carcano bolt-action rifle, and a bunch of cash in the desert. Evidence in the car suggests that its driver crashed it in late 1963.

Before long, the discovery of the car and Williams's indignation at local capitalist exploitation of poor Mexicans are followed by the arrival of a black-suited fed played by Kurtwood Smith. The border patrolmen, deep into their investigation of illicit plane landings, interview an aging prospector, who tells them on the step of his trailer that he “wasted 40 years of my life as an aeronautical engineer for a company called Convair,” and he knew the sounds of an airplane when he heard one.

“You ever heard of Convair, son?” the prospector asks Kristofferson.

“Yessir,” Kristofferson answers back. The prospector is murdered not long after.

The time at which Flashpoint was made, in the mid-1980s, marks the unofficial peak of the broad disinvestment that many people correctly associate with the Reagan era. An early conflict in the movie is the border guards’ resentment over being replaced by computers, which their commanding officer helpfully explains is being done on new orders from Washington.

An anomalous boom industry of those years, however, was the defense business. Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger (later indicted, convicted, and pardoned for his role in Iran-Contra) successfully sought a defense “spend-up” that temporarily offset a largely declining military pie. New military budgets allocated more dollars for missiles and air- and space-based technologies, and fewer resources for troops, military bases, and the like. Engineers more fully replaced the assembly line.

The murdered prospector’s ex-employer, General Dynamics, and other military contractors have prospered in the 2020s just as they did in the 1980s. While the Dow Jones has been down six percent over the last 12 months, and the U.S. is still under threat of economic recession, GD stock is up more than 17 percent. On Jan. 4, Toronto’s National Post reported that “Super Bison” armored vehicles had arrived in Ukraine after manufacture by GD in London, Ontario. On Jan. 6, Secretary of State Tony Blinken announced $3.75 billion in new military aid for Ukraine that includes missiles co-produced by Raytheon and General Dynamics, which can now be fitted for use on ex-Soviet launchers used by Ukraine. Jack Kennedy is long dead, but Convair is doing just fine, as are all of its friends.

Yours Truly,

The American Friend