Welcome to Defector Music Club, where a number of our writers get together to dish about an album. Today, Dave McKenna, Luis Paez-Pumar, David Roth, and Lauren Theisen explore Bruce Springsteen's 1982 cult favorite Nebraska.

David: Friends, we are gathered here today to discuss a grim, spare, old album by the foremost living New Jerseyan. The record is Nebraska, the New Jerseyan in question is Bruce Springsteen, and the whole thing is kind of haunted and half-depressed. I do not know why everyone thought I should be the first person to say something about such an album, but as the oldest and saddest New Jerseyan on the staff I was delighted that Lauren picked this record, which has fascinated me since I was a teenager. I love it but find it kind of difficult to talk about. Not because I don’t think it’s great, but because it feels somehow too on the nose for me, being who and how I am, to be like “Oh you like Bruce Springsteen’s anthems? You should really check out his Mood Disorder Album, which has virtually no instrumentation, was recorded on a four-track, and seems to have been co-produced by a ghost.”

Lauren: Yeah, I was interested in revisiting this album because its sheer lack of Bruceiness has always made it stand out, sometimes for better and sometimes for worse. Springsteen’s been with me basically all my life—he was one of my mom’s Big Three, alongside U2 and R.E.M.—but when I was in high school I was hanging out with cool kids who were into punk and rejected anything that sounded pompous or overdone or arena-ready. (A really funny bit I once did was burning like a Stooges CD or something and giving it to one of them with Use Your Illusion written on it in unignorable permanent marker.) Most of what Springsteen did got slotted into that blowhard rock-star category. Nebraska was like the one album that you weren't supposed to be embarrassed about liking.

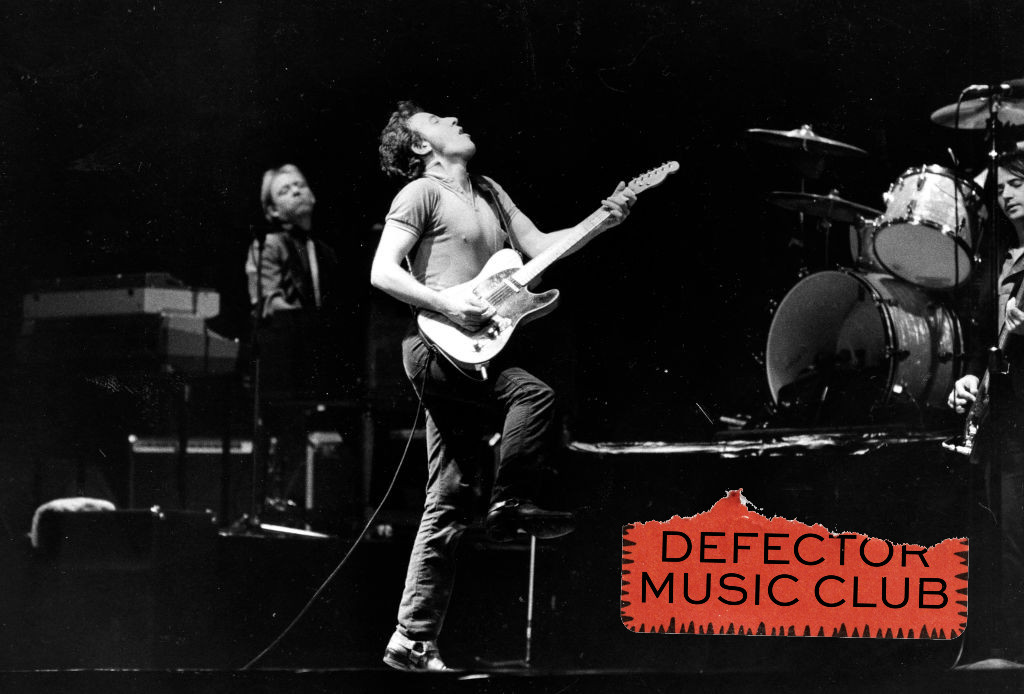

Now, though, I rarely have any desire to listen to it. I think Springsteen’s E Street live stuff from the mid-to-late-’70s are some of the greatest recordings of all time, and Nebraska can sound dull in comparison. The Bruce that shouts “ONE TWO THREE FOUR!” on stage is very much My Bruce.

Luis: I have a confession: Despite working in and around sports journalism for most of my adult life, I am not a Bruce Springsteen guy, at all. I have never investigated his music beyond, like, the two "Born..." songs that everyone knows and “Dancing in the Dark.” It's a blind spot, and as I moved to New York from Florida to attend college, it became a willful one in the face of all my new New Jerseyan friends.

That is, except for Nebraska. I don't really remember how I first heard it; I think it was thanks to a girl I had a crush on, as all the best music is found. But I do know that I've returned to it over the years, and so I willingly jumped at the chance to talk about it despite not having any real context for what the album came from, in terms of Bruce's career, and whether it had any portents for what was to come. All it took was one time listening to "Atlantic City" and its massive chorus to lock me back in.

Dave: My confession counters Luis’s. I was a massive Bruce fan as a lad. I’m old, and he was really big in the D.C. area early on, thanks to promotion from the alternative/stoner station WHFS, so I had his first two records. I remember sitting in the school library when I was 14 reading the Time and Newsweek cover stories on Born To Run just in awe, then sitting on the hood of my still-buddy Louie’s Pinto listening to eight-tracks of that record and getting all fucked up. I got to see him, with Louie, on the Darkness tour at Cap Centre when we were 15, and it was stupendous.

But I turned on Bruce like an overbred Doberman after The River. I remember the moment I dropped him: I went to both shows he did on that tour at the Cap Centre, and he was sitting on the stage and letting the crowd sing "Hungry Heart," and it was cheesy, and I remember thinking, “You don’t have a wife and kid in Baltimore, Jack!” Plus, I counted at least 10 songs on The River where he was calling out a “little girl,” and he’s some dude in his 30s. Then it hit me that Meat Loaf was just a Bruce impersonator, as Todd Rundgren would later admit.

I’m sure I was at a point in my life where I just wanted to change, and London Calling was a cooler double album than The River. But Nebraska was the anti-River, an equal and opposite reaction—no callouts to little girls or Meat Loafesque bombast—and I respected that. Three chords and the truth on a four-track cassette recorder. Though I never fully returned to the Bruce fold, I’d still listen to that record over any others in his catalog.

Luis: This album is completely separate from the broad cultural footprint Bruce has in my mind, and so I'm curious to see how it compares for y'all, not just in terms of quality but also in terms of moods/themes/vibes, whatever you want to call it. Lauren, you mentioned that it felt like his one “not embarrassing” album, at least when you were younger. Similarly, I consider this his Auteur Statement. However, by stripping everything down (and, as far as I understand it, letting most of these songs go on the record in their demo form), is there a bit of the Bruce Magic lost here for you?

Lauren: Yeah, when I want this kind of sparse, lonesome guitar music, I go to Townes Van Zandt or something, because he does it with more soul than anybody. To me, Bruce at his best is loud and ready to party and packed tight with a bunch of guys trying to fit their instruments around each other. It’s chaotic and primal and desperately horny but also just smart enough to keep your head engaged at the same level as your heart. Nebraska is not that.

David: That’s always what interested me most about the record. I knew the anthems growing up, because I was a child at something like the moment of Peak Springsteen. The first songs I remember hearing played on purpose in my home were on Born In The U.S.A. I didn’t hear Nebraska until much later, and while it’s not a groundbreaking observation that this is both demonstrably the work of the same artist and something like the sonic opposite of his other stuff, it was absolutely groundbreaking for me, and formative, too, I guess. I have always been drawn to music and movies and books that feel like departures, where you can feel the friction between an artist and their ambitions, and the limits of technical or just human capacities in the process are palpable and present, and where there’s a sort of straining at the norms and expectations.

One of the things I’ve found most interesting about this record, beyond a few really beautiful songs on it, is that as Luis said it’s functionally a demo, and that a lot of the songs Springsteen wrote for it wound up on Born In The U.S.A. in a more conventionally “finished” state. You can listen to a song like “I’m On Fire,” which is pretty understated by Big Bruce standards in its finished form, and imagine something like the version that Springsteen recorded into his tape machine in a fancy house in Monmouth County—without the synthesizer, the metronomic drums. It’s fun for me, as someone who understands music primarily as a form of magic, to see that process so clearly. I guess that’s another way this record was formative for me: I didn’t know that I liked lo-fi stuff until I heard this record. It’s funny that the first and most bombastic artist I can remember listening to also brought me that.

Lauren: I’ve had a harder time imagining a lot of these songs in any more of a finished state than they arrived. “Atlantic City” is the most traditional Springsteen epic, and that one has some full-band versions out there. But there’s a forlornness here that's completely antithetical to the atmosphere of, say, Giants Stadium. Something like “Highway Patrolman,” for example, is just a relentlessly meandering bummer that it’s hard to imagine forcing any crowd of people to sit through, and even the more uptempo stuff, like “Open All Night” and “Reason To Believe” is rooted in a very traditional blues that doesn’t necessarily call out for keyboard and saxophone and all the production values you’d hear on Born In The USA.

David: There’s probably a bigger-sounding version of “Open All Night,” but I can’t imagine one that sounds better than this. Incredible guitar sound, for one, but the idea of making a song this propulsive without any of the elements that I generally think of as serving to propel a song forward—a bassline, a drumbeat—is something of a flex in its own right. It’s just an idea, and some half-stilted lyricism, and it’s clear as a fucking bell.

Dave: Damn, I do love “Atlantic City,” Lauren. I’ll take it in any context. The Band’s version kills me, even knowing Robbie Robertson wasn’t around by then. “I got debts no honest man can pay” is a line so great Bruce used it twice on the same record! I try to drop it into emails and casual conversations all the time. I gotta say I quote Nebraska more than listen to it. There's just a meanness in this world, you know?

Luis: These songs are fucking DARK. Starting your Artistic Statement Album with a song about a serial killer is a strong gambit, and the mood doesn't really pick up from there (at least until the last song). Some of these make me almost uncomfortable while listening, "State Trooper" and "Highway Patrolman" especially. In that way, the instrumentation makes sense. The songs feel claustrophobic in a paradoxical way, because there's so much space in them where other instruments could have gone. (Except for "Open All Night," which is almost jaunty in comparison.) I don't want to read into his intent here, but if he wanted the 40 minutes to feel like a suffocating fog, he accomplished it almost too perfectly.

Lauren: “Mansion On the Hill,” “Highway Patrolman,” and “My Father’s House” were three songs in particular where, when they started, I was just immediately like, “I don’t want to listen to this.” But that said, compared to when I was younger and excited simply by It’s Springsteen but GRITTY, I could appreciate the songcraft and some of the subtle variations in style—the sinister aura of “State Trooper” or the wide-open, eerie calm of the title track.

David: I think that’s totally fair. The thing that I always found embarrassing about Springsteen, as a self-conscious younger person who was constantly finding new shit to be embarrassed about, was not the bombastic earnestness of the big anthems but the thing he’d do at shows where he’d like tell a story about his dad for 25 minutes while the band vamped behind him. It felt indulgent—it is indulgent—but it was also the kind of excess I could find closer to home. When the dirge-ier Nebraska songs step wrong to me, it’s in sounding more like those stadium monologues—or just more like someone describing a dream to a therapist, as in “My Father’s House”—than like an actual musical idea. I think Springsteen is in sufficient control of his stuff that they’re still interesting, just as sketches of his process or perspective. But the best songs on here aren’t just better than the less-good ones, they’re somehow more fully songs to me.

Luis: I think I like that monologue aspect here. Each of the characters he's singing about sound like, if not fully-realized people, at least stock characters with enough depth to them to make their stories stick with me after the album ends. To go back to "Atlantic City," I have often wondered what the protagonist was going to do that was so dangerous.

The sense that some of these songs are incomplete in a fundamental way only heightens that for me. Maybe Bruce is a good actor here, but the almost fly-by-night nature of the recordings makes them feel like they are pulled from his life, when they're not more broadly descriptive (the title track being the best example of that). So, I disagree with your take, but not in a particularly adversarial manner. I just think the songs that sound less like songs and more like ramblings really do it for me as much as the ones that were ready to go.

This is a bit of an aside, but as I was listening to the album this week, I thought, "Man, this sounds like it could be in Johnny Cash's wheelhouse!" Little did I know that Cash covered two of these songs! Wow! We love coincidences!

Lauren: I’m going to repeat my Townes comparison. At times Bruce’s voice sounds like he’s going for an exact impression of Live at the Old Quarter. And frankly, that costume makes me slip into McKenna Mode a little—you didn’t kill everything in your path, Jack!—but ultimately I appreciate this experiment as a counterpoint to all the bombast he made so brilliantly. I can’t say it doesn’t deepen my understanding of his artistry.

Dave: The Townes name-drop is big for me here, because when Nebraska came out I’d pulled out of Falls Church, Va.—a town full of losers lost one—and ended up in West Texas. Out there I discovered all the Texas singer songwriters of the day—non-commercial outsider storytellers with guitars like Townes, Jerry Jeff Walker, Guy Clark, and my fave by miles, Joe Ely and his Lubbock cronies in the Flatlanders. With Nebraska, Bruce was clearly going for what those guys were putting out—sad sack characters from places where darkness ain’t only on the edge of town—and their output seemed more organic to me. It was several years before I found out Jerry Jeff was actually a New Yorker. (But, man, there ain’t many barroom anthems cooler than “Up Against The Wall, Redneck Mother.”) It was hard for a longtime Bruce obsessive weaned on “It’s Hard to Be a Saint in the City” to take his Oklahoma accent, but even so I think on “Used Cars” Bruce aped the Townes mood pretty okay.

David: Bruce’s tendency towards that kind of imitation is another one of those cringe-y aspects that I reflexively grade on a curve. Like he made a record in full Woody Guthrie cosplay, too, and it’s also good. All the different people he’s imitated—and there are some cooler-coded homages on here, too; “State Trooper” could be a Suicide song (or demo) even without the jarring shout-in-the-dark stuff—have by now given Bruce this weird affect/accent where he doesn’t really sound like he’s from anywhere in particular. But I think that’s how writers all work, to some extent. Or anyway, it’s how I work: You assimilate stuff that works for you and make it part of what you want to do, and you come out of it sounding like yourself. What’s fascinating to me about this record is that you can sort of see both the artist he was and was trying to be at that moment, and all the different stuff he was aiming at or just aping. It’s a demo. It’s not finished.

Lauren: I’m not sure exactly how it all went down in '82, but I sort of miss this idea of, you could be a Bruce Sprinsteen fan, and you could go out and buy the new Bruce record, and it just has this completely out-of-nowhere horror to it that you’ve never heard from him before. That kind of unannounced, uncalculated veer to the left that you force a fanbase to travel on because they’ve already spent their 12 bucks on you. Plus, the fact that this is the prelude to the biggest moment of his career in Born In The USA makes it even more strange but also pretty much impossible to dismiss or ignore.

David: I think that’s great, too. This is as robust an example of Trusting Your Stuff as I can imagine, absolutely to the point where it verges on the self-destructive. I guess you kind of have to care about Springsteen to care about that part, but as a teenager hearing this for the first time in the 1990s I was both sufficiently in the tank/familiar with the lore to appreciate the risk it represented. It’s funny that this is something of a through-line to the records we talk about in here—Scary Monsters, too, was kind of an attempt to reset the terms of an artist’s relationship with the public as much as it was a sonic departure. It was also that, and so is this, but there’s an assertion of agency in both records—indulgent, defiant, whichever—that sort of rhymes to me.

Dave: One weird thing about Nebraska that probably means nothing is that I’m not sure I ever heard this record on a record player. Nebraska was consumed in cars on a cassette. His next record, and return to bombast, Born in the USA, was the first album ever released on compact disc.

Luis: To Lauren's point, one of the things I learned about this album early on is that it was the first of his to not have a corresponding tour. I can't imagine him playing these songs in front of an audience, at all, even though I'm sure he has in the years since. The album experience feels too personal, too raw, too brutal to be shared with the immediacy of a concert. You can sort of "trick" an audience into following you down these depths on record, but it feels like a harder sell in person. How do you even do this without turning it into some sort of hokey "Bruce Goes Acoustic!" gimmick?

Lauren: If you hear the stuff on the Live 1975-85 release, they sound weird. “Reason To Believe” is like a funny little bop. “Johnny 99” sounds like someone just forgot to add the rest of the band to the mix. And “Nebraska,” worst of all, is like the opening to an Oscar bait movie about the plains. To answer your question: I think when you’re a superstar who brings a giant crowd to your shows, you’re granted, like, one of these little departures while the casuals go to the bathroom.

David: That’s interesting to read, the way the songs do and don’t work when getting the full-dress Bruce In Concert experience. It’s a big part of the mythos of the album, but I think the recognition on his part that these demos actually were the record, and then letting them become that, is maybe what I admire most about it. There’s obviously this conflict between the songs that Springsteen had in his head and the ones that would fill arenas in time, but there’s nothing necessarily wrong with a song that doesn’t fit that remit. I don’t know that it’s brave for an artist that writes Big Songs to write an album of small ones; I imagine you don’t have much choice there, and have to kind of take what your gift gives you. But I admire that he respected those songs enough to let them be small. I think “Atlantic City” is one of the loveliest songs Springsteen ever wrote, and as careful a bit of lyric-writing as I can imagine, and while there is obviously a version of it that layers on the instrumentation and bathos I feel like he kept this one the right size. It’s a sandcastle, not a mansion.

Defector's Favorite Jams Right Now

DJ Ramon Sucesso and DJ Blakes

DJ Ramon Sucesso, one of the biggest stars of the current wave of Brazilian funk, is to me a more captivating DJ than producer, so this video of him on the turntables playing his latest EP is the best way to experience him—six joyful minutes of him bopping along to his creations, flinging crossfaders and twirling knobs and whirling his DJ controller's wheels of plastic, weaving together four songs of typically frenetic, irresistibly danceable music.

My favorite song of the set is the last one, "Quando Eu Te Chamar," but the one I most deeply connect with is the first, "Cardume." Part of that connection comes from its short, repeated, unmistakable sample of Eve's "Let Me Blow Ya Mind." An aspect of getting older that I appreciate is seeing songs from my youth flipped in fun new ways by today's youth, in the same way that sample-based hip hop producers of my youth flipped the songs of older generations. One of the delights of getting into Brazilian funk is hearing little nods to the past like this one, or the split-second "Go!" drop DJ Ramemes loves to pepper his tracks with—just a penny's worth of 50 Cent that makes the song all the richer.

I had a similar thought earlier this week while listening to the new DJ Blakes album Mandelãoworld. As you might surmise from the title and would surely get after seeing the cover art, Mandelãoworld is a play on Travis Scott's Astroworld. The references extend into the music itself, which collects bits and pieces from Travis's body of work and funkifies them, taking what is often corny and derivative source material and turning it into something awesome.

The Eve sample on "Cardume" and the Scottian references in Mandelãoworld do a great job of capturing baile funk's playful irreverence and the deep cultural well the artists draw from. It reminds me so much of the early-00s mixtape era of rap—when producers were venturing outside traditional soul samples in search of fodder to flip, rappers were finding ways to pull from and parody pop culture, and a handful of graphic designers had struck upon that hilarious and beautiful visual sensibility that defined the era. But even more than how it rhymes with my own particular past, what these little artistic decisions do is show that, even across a big gap in age and culture and language and geographic distance, we are all really much closer to one another than you might think.

-Billy Haisley

"I Figured You Out"

I'm a gigantic fan of Elliott Smith, and it sort of disappoints me when I tell people that and their response includes the word "depressing." Like, yes, it's hard to extricate Smith from his death and from that suicide attempt scene in The Royal Tenenbaums. But to me, most of Smith's songs are beautiful—fragile like a flower but also saturated with emotion and a deep care for his craft. There's nothing less depressing to me than that.

A hidden gem of Smith's catalog is "I Figured You Out," a reject from his masterpiece Either/Or that he thought sounded too much like the Eagles. ("You want to hear a stupid pop song I wrote in about a minute?” he once said before playing this at a show.) Lyrically, it's a kiss-off in the vein of Dylan's "Positively 4th Street," and the version he recorded counterpoints those lyrics with an easygoing guitar, airy synths, and his usual angelic voice. It's an all-time favorite of mine, but I might even prefer the song as done by Mary Lou Lord, who grounds the words with just a bit more confidence even as she maintains Smith's soft delivery. The minute Smith spent writing this is better than any minute I'll ever have.

-Lauren Theisen

The Bevis Frond - "Heavy Hand"

Youtube's genius algorithm sent me this Bevis Frond tune this week, and like everything by Nick Saloman, the dude behind BF, it deserves a bigger audience than just my fat old white dude demographic. Saloman can make you clench your fists and bang your head and cry all in the same song. If you don't love this and his entire catalog after giving 'em a chance, we would never get along.

-Dave McKenna