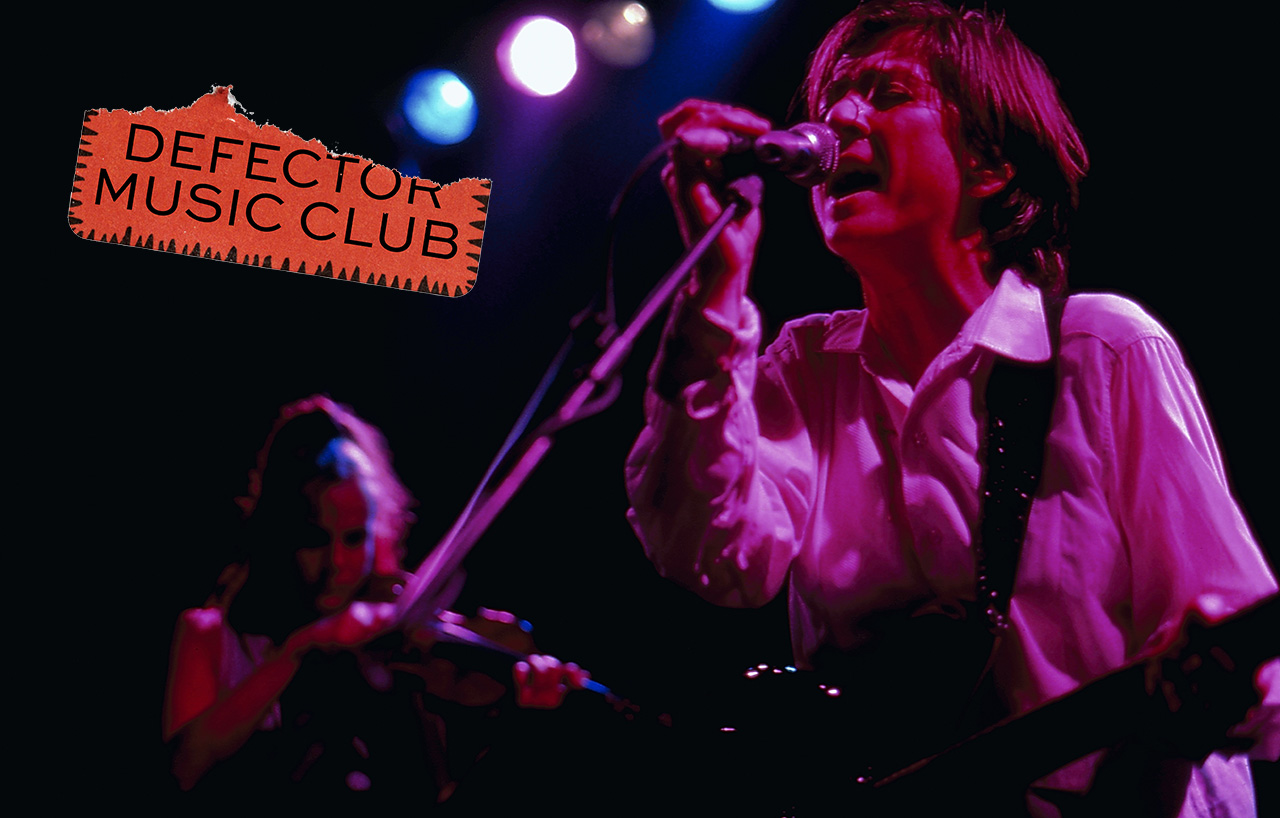

Welcome to Defector Music Club, where a number of our writers get together to dish about an album. Here, Giri Nathan, Patrick Redford, and Lauren Theisen share their thoughts about the ground-breaking 1979 debut of The Raincoats.

Lauren: The year is 2011. I’m an alienated queer kid in suburban Michigan. Naturally, my appetite for music is “everything Kurt Cobain ever said was cool.” I share this interest with a couple guys I know, and eventually that puts into my hands a CD copy of 1979’s The Raincoats, which included liner notes from Kurt. “Whenever I hear it I'm reminded of a particular time in my life when I was (shall we say) extremely unhappy, lonely, and bored,” he wrote. “If it weren't for the luxury of putting that scratchy copy of the Raincoats' first record, I would have had very few moments of peace.”

I don’t know if I loved it quite as much as he did, but The Raincoats became a record that lived alongside me. It felt like music played by normal people, ones I could hang out with in a garage. It had the pent-up energy of a yearning would-be escapee and a topsy-turvy sense of melody. It even gave me cred with non-punks because I knew what Heath Ledger was talking about when he namechecked them in 10 Things I Hate About You. Revisiting it here, going front to back for the first time in quite a while, was a real treat. How was it for you guys?

Giri: This was actually my first time through this record. I distinctly remember downloading this record on Soulseek when I was deep in a post-punk and folk-punk phase in high school—typing the word “punx” a lot; listening to Defiance, Ohio; things of that nature—but for some reason I lost track of The Raincoats, even as I was getting into contemporaries like This Heat. The prompt for this Defector Music Club session was actually just seeing Cobain’s list of his 50 favorite albums and feeling very stupid that I had never dug into this one. What a treat it was.

Patrick: Lauren, I also probably stumbled onto this one in 2011, when I was just at college and getting into post-punk for the first time and listening to the first Gang of Four record ad nauseam. I came across this album first by way of “Lola,” which I suspect is a sort of common gateway drug experience, and I remember being really into the album pretty much instantly. A decade later it still hits, maybe even harder. It’s hard to think of many other bands from the late-1970s—or ever, really—that could be this pretty and this discordant at the same time, so consistently. Like, I am actually not sure whether to file the gecko-like squicky breakdown on “No Side To Fall In” as pretty or discordant. Why not both?

Lauren: It might be worth starting with this exchange from 20th Century Women, a fantastic movie that is set in 1979 and uses “Fairytale in the Supermarket” in a scene where this cool version of Greta Gerwig is influencing Annette Bening’s son to be cooler.

“OK so ... They're not very good, and they know that, right?” Bening says.

“Yeah, it's like they've got this feeling, and they don't have any skill, and they don't want skill, because it's really interesting what happens when your passion is bigger than the tools you have to deal with it. It creates this energy that's raw,” Gerwig responds. “Isn't it great?”

That “Isn’t it great?” was a guiding star for me in my tumultuous early 20s, but I think on this particular Raincoats listen I was opened to just how skilled the Raincoats actually are, in a sense. This record feels less like destruction and more like deconstruction, pulling apart the successful music of the classic rock era (like “Lola”) and rearranging it in a way that describes their world better. It takes remarkable vision and talent and hard work to be able to do that, especially in a way that echoes across future decades.

Patrick: Yeah, I suppose that while the scrappiness of this record is an inextricable part of its creation myth (I read an excerpt from the 33⅓ on Pitchfork and it was mostly about the mechanics of squatting in London in the 1970s), it doesn’t ever really "sound like shit," in the way that you might think it would if you’d only read about how this one squat was so dingy there were mushrooms growing from the walls (also, that sounds cool). You can hear a real sense of collective joy in this record, and I think in particular the slightly discordant chorus on “Off Duty Trip” is a useful way in here. Like you said, deconstruction. They’re all kind of cooing over each other, winking about joining the “professionals,” and it’s like if you added technique back to the classic All Passion, No Technique formulation of post-punk. My point is, Annette Bening’s kind of being a clown low-key.

Giri: It’s such a cozy record. It invites you into the squat. I couldn’t stop thinking about the chemistry between the bandmates. I read—I think in that same 33 ⅓ excerpt—that they pretty much only practiced their instruments together, and you can feel that in every track, that deceptively simple looseness and cohesion, the noodliness that never feels out of pocket. I love Cobain’s bit about how he felt like a voyeur: “When I listen to the Raincoats I feel as if I'm a stowaway in an attic, violating and in the dark. Rather than listening to them I feel like I'm listening in on them. We're together in the same old house and I have to be completely still or they will hear me spying from above and, if I get caught—everything will be ruined because it's their thing.”

Lauren: The closing moments on this record reinforce that private feeling. “No Looking” is mostly a song about being ignored by a lover, but as it speeds up into this cathartic climax, the repeated line feels more like a command: “No looking at me, no looking at me…” It becomes like a celebration of marginalization. In that way, it’s welcoming to some, secretive to others, and straight-up hostile to those who don’t get it at all.

Giri: The way that marginal feeling gets channeled was very interesting to me, if I contrast it with some of the snarlier, testosterone-fueled hardcore and punk that’s coming from a similar place of alienation and following that feeling to a much more violent sound. Here, marginalization is in service of coziness and intimacy, without losing its bite, necessarily. I gave the record another spin on a run this morning, and even as I was literally transporting my body over some distance I felt like I was sitting on the same busted sofa under a leaky roof the whole time.

Patrick: That specific suite of feelings is why post-punk as a genre has always resonated way more with me than normal-style hardcore. Like sometimes it is fun to think yes, in fact I will “Rise Above” but its utility is so limited to me. You can’t feel like that all the time, and there’s no subtlety to that feeling.

Lauren: Without getting too strict about genre, old-school punk can be about taking a big group of people and shooting them all out of a cannon in the same direction, whereas I think there’s more of a communal exchange in this Raincoats release, especially when it draws from queerer, clubbier spaces like disco. You need to trust it and bring yourself into it, and then it returns the favor. It’s music that will start a conversation with your neighbor. It revels in that feeling of just sharing oxygen with the people you’ve let into your heart. Maybe that sounds overwrought, but the way that these instrumental and vocal parts interlock with each other, in that semi-mythical old house Cobain mentions, creates an almost tangible sense of home within chaos, solidarity within oppression.

Patrick: There’s a sense of propulsiveness (I also listened to this album a few times at the gym, and it really worked as an internal cinematic experience) that moves the songs even in their quieter moments, and all that intimacy is balanced so well by, like what Giri said, the way they sound like a band that trusts each other so much and plays off each other so well. Not to boil this all down to something so simple, but doesn’t that guitar sound go crazy?

Giri: I’m on the record saying we need to Make Guitars Jangly Again. Joe needs to put a guitar in every household. We need to channel white alienation into puzzlebox post-punk records and not, like, storming the Capitol.

Lauren: Vicky Aspinall’s violin on top of those guitars is so helpful, too, because they can sound like they’re scratching all their equipment beyond repair without actually sacrificing a song’s core rhythm.

Giri: I love all the instrumentation on this record. The violin definitely hits home, that Velvet Underground influence; Ana da Silva’s keyboards add a nice woozy layer of atmosphere; the saxophone just burbles away as the songs lapse into mini-breakdown. At times it feels like they’re playing toy versions of these instruments, masterfully—operating within constraints.

Patrick: I love that, and I think I feel it most directly on “The Void,” maybe my favorite on the record and an extremely simple song—you kinda get what’s going on once you read the title. It achieves something like transcendence by force of wooziness, with the tempos skittering around as that violin lurches. I listened to the Hole cover, and while the grungier guitars crunch up the breakdown much more thoroughly in a way that should make it appropriately heavy, what I was mostly struck by was how much more emotional impact the spaced-out multi-instrument version had.

I want to return to something you said a bit earlier, Lauren. I feel like a significant part of this record’s legacy is that it was a punk record made by four women, at a time when that wasn’t as much of a thing. That the most popular song is a cover of “Lola” also feels significant. There’s not quite a winkingness, but there’s a sense that they really were using the form and going in a truly novel direction with it.

Lauren: It’s not one of those covers that shows any disdain for the original. The band clearly appreciates the composition. But whereas the Kinks’ songwriting took clever conceits and packaged them so they wormed their way into as many heads as possible, these women take ownership by matching the transgressive, slightly disoriented lyrics with their more homemade, from-the-heart sensibility. It’s not begging to be liked, the way the Kinks’ hits are, but it’s still extending a hand that people can then grab or not grab.

Giri: I love the image of them extending a hand to a listener, and I'm wondering if there were any particular moments where you guys consciously did not grab the hand. For me, it’s “In Love,” a song I enjoy in its lyrical concept and basic structure, but every time I get to the chorus I hear the seagulls in Finding Nemo. There are many forms of dissonance I enjoy, but the arfing sent me over the edge in this instance.

Patrick: For me it was that song’s predecessor, “You’re A Million.” It stands out as a more straightforward song than most of the others around it, and while the jangliness is great, they do only one thing. So many of these songs feel like something from the future, and that one doesn’t quite.

Lauren: The natural inclination, when you’re talking about a band from over 40 years ago, especially such an influential one, is to look around now and be like, “Well, where did this lead?”

Giri: Let’s follow that question for a moment, though. I can see throughline from this record to bands thirty years later like Liars, taking things in a dancier direction, or Xiu Xiu, getting kooky with a xylophone. I’m absolutely still in a phase of my music-listening life where I look at everything and see Unwound, but I’m reminded of the parts of their career where they let some air into their alienation, and the sound grew sparer and less overtly angry, and they grooved with one another in way that felt precarious, liable to fall apart at any time.

Lauren: Did someone say 100 gecs? No? Well, I still think “Dumbest Girl Alive” is a modern “Fairytale in the Supermarket.”

Patrick: I’ve referenced them earlier, but I see some of their tempo-switching DNA in Protomartyr. The guitar sounds and scrappiness come through in Double Nickels On The Dime, though that album came out like five years later, so I might be cheating with that one. Also, it’s about driving your car, while The Raincoats is a canonical Train Record. I am also a big Dry Cleaning stan, and they’re the only band I’ve heard in the last decade that can write songs as simultaneously playful and propulsive as the Raincoats. In my mind, “Scratchcard Lanyard” is a song the Raincoats could have made if they lived somewhere with reliable electricity. The two bands’ singers sound nothing alike but for their accents.

Giri: I was thinking about Dry Cleaning constantly as I listened to this record. Must be a London art school thing. It’s like they’ve digested the advertising and mass communication of the intervening forty years and made their own version. It’s definitely all some gloomy-ass, London skies music, and it's nicely suited to the weather we’ve been having here lately.

Lauren: For all the possible connections, though, I love this record as its own thing and I think it lives on as that—of its post-punk time, yes, but mostly this cherished object that can be a companion or a mind-blower or just a fun thirty minutes for those with a matching sensibility. When I listen, I don’t hear any distance at all. The Raincoats are forever as close to you as you let them be.