We know two things about Game 7 Monday night in Boston to be irrefutably true above all others. One, the game cannot remotely resemble Game 6, and we all must accept that as surely as gravity. And two, Stan Van Gundy cannot spoil it no matter how well he can see the future.

And the second one is the thing that lingers most—well, last anyway—as Sunday rises on Boston's preposterous 104-103 victory over Miami to force the unlikeliest seventh game in best-of-seven history. It is Van Gundy helping set up the Celtics' final inbounds play with a toss-off line about Miami's Max Strus needing to pay heed to inbounder Derrick White, just as the nation was fully committed to pay attention to almost any one of the other players.

This seemingly cheap diversion from the obvious last-shot obsession with which we all viewed the end of this magnificent piefight became absurdly prophetic. With three seconds left (more or less) and the Heat up 103-102 after three clutch free throws by Jimmy Butler, the Celtics called time to inbound the ball in the forecourt for a last chance to save their season. White, as the least obvious offensive option, was asked to inbound, and as he succeeded in his principal duty of getting the ball to teammate Marcus Smart, I took Van Gundy's bait like a fool and found myself watching White with more than justified curiosity.

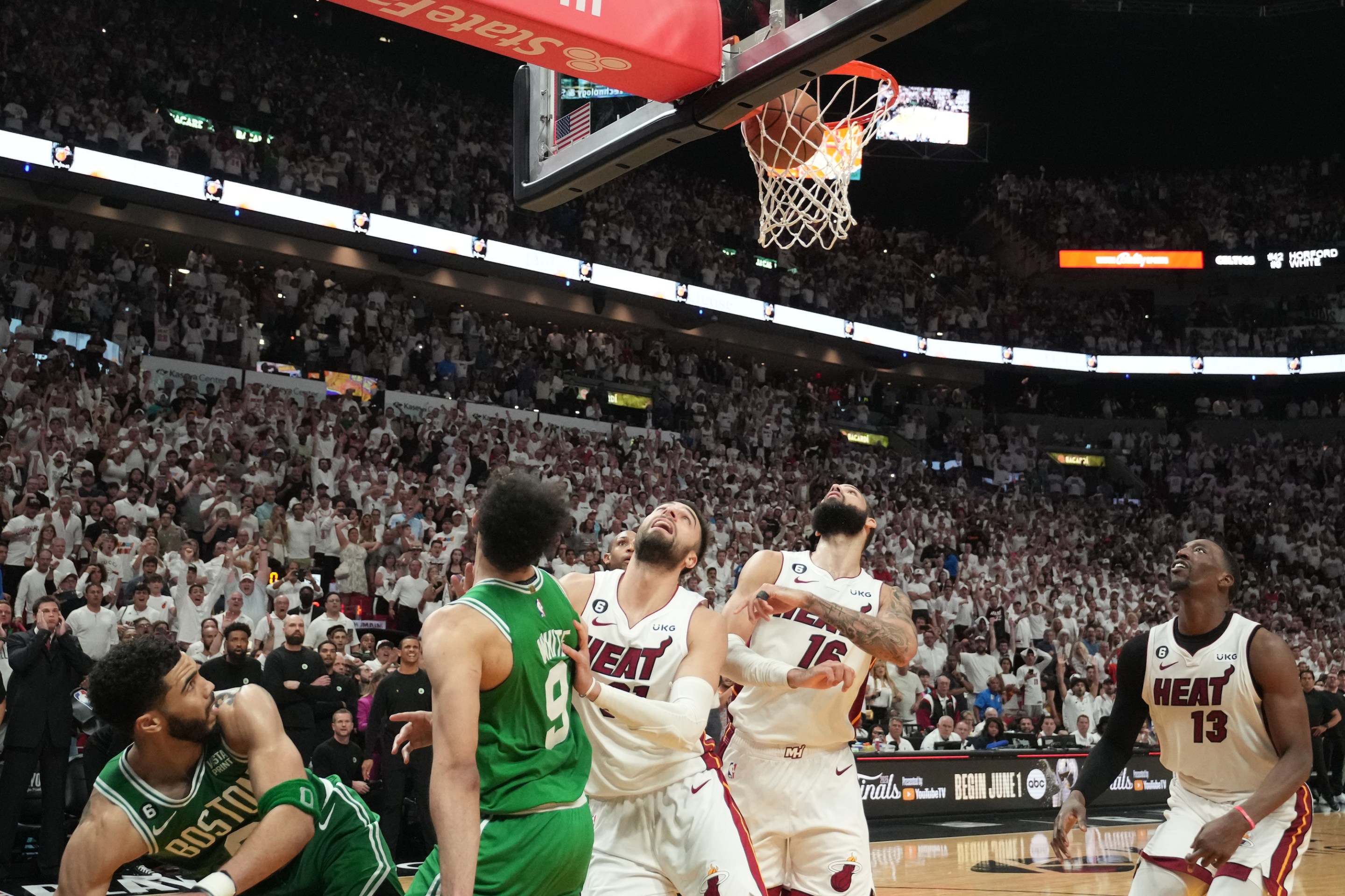

Smart did his job, getting off an off-balance and well-contested but completely correct turnaround three over Gabe Vincent, and White took off toward the basket for the rebound that almost certainly could not find him in time. Strus was momentarily distracted by the specter of Jayson Tatum at nearly 40 feet from the basket, White beelined to where the ball headed after rattling out of the basket, got to the miss and got off the successful follow with one tenth of an inch left in the dagger to end this towering achievement in athletic entertainment with a cliffhanger worthy of Scheherazade.

Van Gundy knew because it is the job of every coach-turned-analyst to consider all potential options in the interminable hours during every time out, and to speak them all even if none of them ever come to fruition. One could certainly hear Hubie Brown doing the same thing because Hubie Brown has spent all 17 decades of his life doing just that while every other broadcaster would drone on endlessly about Jayson Tatum and Jaylen Brown and Butler and Bam Adebayo and the Heat in the Finals and blah-blah-blah-de-blah-blah. The inbounder doesn't get the attention because with three seconds left, the inbounder can't be in a position to win the game.

Except White was, to his eternal (read: for two more days) credit. On a night in which there were already multiple reasons for each team to cheer and lament their deeds and choices dozens of times over, he was the one who pursued his one-in-a-hundred chance made just that much more possible by Strus doing what anyone would do—getting distracted by the other team's best guy instead of following the other team's fifth best guy.

Over the next two days before Monday's denouement, much will be said about Butler's awful shooting and brilliant free throws, Boston's continuing suicidal fixation on shooting threes poorly when their ability to harm Miami inside the arc remains evident to all, about the 1951 Knicks and 2004 Red Sox, and all the absurdities that made Game 6 both an instant classic and a swiftly ignored setup to the Game 7 that cannot possibly match it for peaks or valleys. Two game but flawed teams have created a glorious clash between the hearts and heads of the characters.

But these three things above all others must be said about Monday night. Stan Van Gundy will be heeded no matter what tumbles from his motorized yap, the time will be checked at every opportunity, and the inbounder will be guarded on every out-of-bounds play. That is a subtlety of the modern game that is about to have a new, if brief, heyday.