Daniel Slosberg wants me to watch a TV clip. It's from an October 1998 episode of The Roseanne Show. Among the guests is Diana Nyad, who at the time was the most famous female swimmer this country ever produced. Slosberg, a former participant in the niche sport of endurance swimming where Nyad toiled, directs me to the part of the show where Nyad recalled with passion her participation in the Olympic trials, where she claims to have competed as a 17-year-old hoping to secure a spot at the Mexico City Games of 1968.

“I was gonna swim a 100-meter race, lasts about a minute, and either wear the USA uniform and stand up on an Olympic medal stand, or not and go on to the rest of my life,” Nyad said as the host, Rosanne Barr, and Olympic legends Mary Lou Retton and Jackie Joyner-Kersee, looked on. “And 10 years of the hours Mary Lou was just talking about, eight hours a day [of training], that’s no exaggeration! Eight hours a day, when you’re 8, 9, and 10 years old! And as Mary Lou said, no one makes you do that! That comes from … guts! And it comes from something deep, deep inside you.

“And I walked out on that pool deck. And I was scared to death,” Nyad continued breathlessly, her fists clenched and waving. “You’re so scared because you’ve given up childhood, adolescence. Your family has given up a lot. And this one little moment, it’s just like the weight of the world on your shoulders. And a friend came, a 16-year-old girl, with such wisdom! And she shook me, like, shook me awake! She said, ‘Diana, I see what’s going on with you. It’s like the weight of the world is on your shoulders! You’ve got to stop thinking about this, 10 years and what it all meant and it’s all going to be for nothing if you don’t make it! Let’s think of something small like the tennis players think of the fuzz on the tennis ball. Why don’t we just pick a little fingernail!’ Not very poetic, but it was so true! She said, ‘Why don’t you dive in and swim with your shoulders and your guts and your heart, and when you finish, don’t look at the scoreboard. Don’t figure out if you’re in the top three and you’re going to Mexico City! Close your eyes and say, I couldn’t have done it a fingernail faster! And she said, ‘I guarantee, you can say that, everything will be all right.’”

As any fine storyteller would, Nyad ended her tale with a shocking reveal followed by a crowd-pleasing kicker: She didn't make that ‘68 Olympic team. But, using the advice from her younger friend—wisdom she termed “better than Confucius”—Nyad left the trials content and “went on to break world records” and live the best life.

“I did it all,” she said. “So I couldn’t have done it a fingernail better!”

Retton, Joyner-Kersee, Barr, and the studio audience all erupted in applause at the punchline.

As Slosberg can and will tell you, Nyad has told different versions of her Olympic trials fingernail story a whole lot through the years in motivational speeches, though always with the lemonade-from-lemons moral.

And why shouldn’t she? Well, Slosberg’s got a big reveal of his own: “Diana Nyad was not at the Olympic trials,” he told me.

He provided me with various newspaper clippings and links to sites with race results from the ‘68 swimming trials, none of which had Nyad’s name.

But what about Nyad’s shoulders bearing the weight of the world? And that precocious pal with the poolside pep talk offering life-altering wisdom better than Confucius? And all that contemplating a fingernail? None of that happened?

“She made it up,” Slosberg said.

He'd go on to tell me about lots more stories and accomplishments that he and others believe Nyad has exaggerated, stretched to untruth, or wholly invented throughout her career as a swimmer and motivational speaker. Through all this telling he pulled me deeper and deeper into his own life, which for many years now has revolved around attempts to expose the woman who he recently called "the greatest con artist in the history of marathon swimming."

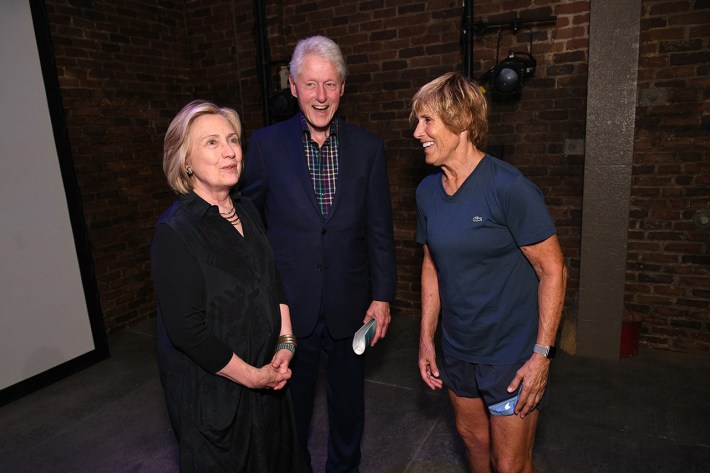

Slosberg's quest for untruth has recently been reinvigorated by Hollywood. In September, the trailer for a feature film based on Nyad's memoir was released. The movie, titled Nyad and starring Annette Bening as the title character and Jodie Foster as her best pal and occasional coach and girlfriend, Bonnie Stoll, recounts the swimming event regarded as Nyad's most momentous: her 2013 crossing of the Florida Straits from Cuba to the U.S. Both Bening and Foster are already being touted as contenders for Academy Awards for their work in the film, which in early press releases the producers said is based on “the remarkable true story” of Nyad’s Cuba crossing.

The way Slosberg sees things, any true story from Nyad is remarkable. He hasn’t yet viewed the movie, but no way that's going to keep him from giving his review.

“She’s asking us to believe a fairy tale,” he said.

Slosburg’s relationship to Nyad is part Boswell, part Lee Harvey Oswald. He said they’ve met only once, at an Ironman triathlon in Hawaii in 1980, when he was competing and Nyad was a correspondent for ABC’s Wide World of Sports. Yet even if he doesn’t know her, he likely knows more about Diana Nyad than anybody except Diana Nyad. For years, he has been devoting ungodly time and energy to finding all he can about Nyad. He’s gone over pretty much everything she’s ever written or publicly uttered, and since 2016 he’s been using her own words against her on his website, nyadfactcheck.com. He said he has made no money from his labors, other than when a fellow marathon swim enthusiast asked readers to chip in to keep Slosberg's site online. "I think it came to around $200," he said.

Nyad’s given him a lot to work with.

“We’re not sure how he can stomach it, but we’re glad somebody’s documenting this,” said Bruce Wigo, former director of the International Swimming Hall of Fame (ISHOF), a group that helped launch Nyad’s marathon swimming career in the 1970s but has since turned hard against her. Wigo seems as amazed by Slosberg’s relentless pursuit of any Nyad untruth as he is by Nyad’s bizarre blizzards of bull.

“Daniel has built up trust in this [open-water swimming] community in a way that Nyad never did,” Wigo said. “He’s not just saying stuff, he’s providing the evidence. He backs up everything he says.”

The aforementioned Roseanne Show clip is posted on the site, along with a stunning list of dates and locations where Nyad’s told different but still fabulized versions of her 1968 Olympic trials story, and the falsehoods she’s introduced in each retelling. There’s an interview Nyad did with Military Life magazine, for example, published in the fall of 1974, in which she said, “I came in fifth. I was only 6/100ths of a second behind third place.” And, during a speech at the 2015 Lake Forest College commencement: "I looked up at the electronic scoreboard, and I was sixth."

You can’t come in fifth or sixth if you weren’t even in the race, obviously. As for that memory about how she learned she wouldn’t be going to Mexico, Slosberg dug deep into the news archive and came away with this: “There was no electronic scoreboard at the 1968 Olympic trials,” he told me.

Slosberg will also tell anybody that will listen that the records from Florida, where Nyad grew up, indicate that she didn't swim meets until she "after she'd turned 13."

So her “no exaggeration” claim about working out “eight hours a day” when she was “8, 9 and 10 years old” just like Mary Lou Retton did? Just more blather, said Slosberg. And, what the hell, it turns out Nyad was actually 19, and not 17, when the 1968 Olympic swimming trials took place.

Slosburg didn’t invent Nyad trutherism. Her 2013 Cuba swim was controversial in the marathon swimming world even before it started. Mostly because she’d spent decades eroding whatever trust the marathon swimming community had in her by padding her résumé and inflating her historical importance to the sport.

While the mainstream media hailed her as a heroic daredevil for spending a reported 52 hours, 54 minutes and 18.6 seconds to cover about 110 miles of the Florida Straits in 2013, chatter among her swimming peers seemed more intent on poking holes in the legitimacy of the swim. The negative buzz centered around such things as GPS data that showed her average speed went from 1.5 mph to at least 3.9 mph for a period of several hours late in the swim, sparking unsubstantiated allegations that she’d received improper assistance along the way, including insinuations she’d spent part of the trip hanging onto a boat or even riding in one. (Michael Phelps's average speed in his world-record 400 meter individual medley swim at the 2008 Beijing Olympics, which he finished in four minutes and 3.84 seconds, was about 3.7 mph.) The attacks on Nyad’s credibility were so quick and so brutal that Nyad was forced to stop celebrating the achievement and defend herself almost as soon as she toweled off.

“I hope they’re not questioning if I’m an honest person,” Nyad told The New York Times in September 2013.

As Nyad knew, her honesty was exactly what was being questioned at the time. Nyad has been earning suspicions since she made her first big splash in American waters in 1975 by swimming around Manhattan in seven hours and 57 minutes.

Nobody, female or male, had ever made it around the island faster. The Big Apple circumnavigation made her a rare non-Olympian swimming idol and media darling immediately. Slosburg said, and his site proves, that she's used the spotlight to revise history to enhance her open-water legacy ever since.

“I was the first woman to swim around Manhattan Island,” Nyad wrote in Find a Way, the 2015 memoir that serves as the basis for the upcoming film. She's made the same "I was first!" boast in interviews and speeches.

“She was the seventh woman,” Slosberg said. Then he provided lots of names, dates, and other evidence to support his version of the truth, which once again tends to have an anti-Nyad bias.

He also directed me to a real strange passage from Other Shores, an autobiography from Nyad published in 1978. In that book, when Nyad wrote about her objectively cool Manhattan project, she listed some of the women who’d circled the island before her. She knew others had come first. And gave some of them credit.

“At some point that wasn’t good enough,” Slosberg said, “and she made herself the first.”

Slosberg has a fascinating collection of documents detailing Nyad’s origin story. They appear to show that the men who first wanted her to be famous didn't focus on her actual swimming accomplishments or the facts when deciding she could be an open-water star. Nyadfactcheck.com has a letter about Nyad sent in May 1970 by ISHOF executive director Buck Dawson to Joe Grossman, a professional marathon promoter based outside of Washington, D.C. In it, Dawson described Nyad as “beautiful, determined,” while outlining a misogynist media strategy to use her looks and faux Greek heritage (Nyad's stepfather was Greek) to “re-inject some glamor into the races.”

“I think finally we have ourselves another Marty Sinn,” Dawson wrote. Sinn was a marathoner from Michigan who in a 1964 Sports Illustrated profile, ostensibly about her athletic prowess, was described as being able to swim “as good as she looks” and having a penchant for swimming nude.

In his response, Grossman seemed thrilled to promote Nyad, calling her “a goddess.” He asked Dawson to gin up a résumé of Nyad’s swimming accomplishments so he’d have something to push besides her looks as he lobbied “the dullards at ABC’s Wide World of Sports” for more marathon swim coverage. The Greek angle and her beauty would be good for business, Grossman said. But it's hard to push a swimmer who wasn't good enough for the Olympics and, other than being a Florida state high school champion in the backstroke, hadn't yet accomplished a whole lot in the water. Grossman needed more.

“Invent something if you must,” Grossman wrote.

Nyad went on to occasionally rub ISHOF brass the wrong way. In a 1979 Sports Illustrated story about the state of marathon swimming, former USA Olympic team coach James “Doc” Counsilman blistered Nyad, who he called "a very mediocre swimmer with a very good publicist.” Counsilman, the head of the ISHOF board of directors when the group began pushing Nyad, ranted to SI about the sport’s “phony-baloney promoters” who helped get Nyad a level of celebrity beyond what her actual swimming talents merited. “Most of her swims have been failures,” he said.

Counsilman, then 58, had recently become the oldest swimmer to traverse the English Channel, a trek that marathoners have always considered as a way to separate the wheat from the chaff. He wanted people to know Nyad didn't make the swim.

“[S]he has attempted to swim the Channel three times," Counsilman told SI, "and has never finished.”

Yet through relentless self-promotion, Counsilman told the magazine, she “gets all the attention” while “more deserving marathoners … go begging.”

Nyad never did complete a Channel swim. But, as a mediocre swimmer with a good publicist would, she got credit for it anyway: A 1977 profile of her in the Minneapolis Star Tribune talked about "the perilous English Channel swim, which she has done twice."

Nyadfactcheck.com went live in 2016. Slosberg added a blog with a similar agenda, Nyad Fact Check Annex, in 2017. He said the anti-Nyad vehemence that inspired the site came from the same stuff that drove Counsilman to bash her in Sports Illustrated decades earlier: He tired long ago of her being the face of marathon swimming, given her accomplishments. He rejected her reprising the media-darling role following the 2013 Cuban swim, which he has never accepted as legitimate.

Slosburg, 66, was an endurance swimmer himself who showed promise as a 20-something in his native California: His double-crossing of the Catalina Channel in 19 hours, 32 minutes in 1978 was hailed as the fastest ever at the time. But he said he knew early on that he had nowhere near the talent of the open-water swimmers he trained with at that time, including Penny Dean, who set a record for the English Channel swim that same year, and Lynne Cox, who went to become world famous in 1987 for being the first person to swim the Bering Strait from the United States to what was still the Soviet Union.

Slosberg thought a good portion of the publicity going to Nyad, through her own relentless myth-building, should have gone to more deserving open-water swimmers whom he called friends.

Slosberg's Nyad-related toils can come off more as a crusade than a hobby, but his site is hardly lacking for humor. Some of its meanest exposés are also its funniest. Like his video compendiums of Nyad claiming that she knows precisely how long it takes, down to the second, for her to sing “The Needle and the Damage Done” by Neil Young “a thousand times” during a marathon swim. (Spoiler alert: She doesn’t really know.) He also has Nyad making the same bogus claim about singing Janis Joplin’s “Me And Bobby McGee” 2,000 times. (Nyad has made identically absurd declarations about John Lennon’s “Imagine,” and Bob Dylan’s “It Ain’t Me, Babe.”) Then there's Slosberg brutally pitting Nyad vs. Nyad on the topic of how old she was when she started swimming; he shows how the older Nyad gets, the younger Nyad claims to have gotten started. The site also devotes lots of digital ink to Nyad's years of insinuations she was on the verge of earning a PhD in comparative literature. (Nyad never earned a PhD.)

Slosberg even has Nyad fibbing about not fibbing.

"It’s true I used to lie. Only to impress myself," she told the Village Voice for a 1976 profile. "I would tell a cab driver a lie—anybody. I don't have to do that anymore."

She may not have had to, but Nyad, whose own manager, according to that Voice story, thought Nyad was overexposing herself in media, was soon after caught lying about the Manhattan swim that earned her the profile.

Other stories truthered by Slosberg, however, are just plain sad. For years, Nyad has told audiences at her motivational speeches about being in a restaurant and meeting a woman with a tattooed wrist who told her immediately that she was a Holocaust survivor from Krakow, Poland. In Nyad’s telling, the woman told her that the tattoo came from "Dachau," the German death camp, where she was taken as a 3-year-old with her mother and sister after the Nazis "shot the father dead" while capturing the family. Then the mother and sister were murdered at the camp, while the 3-year-old was made a “sex slave” for the Nazis for the next three years. Slosberg says he is aware of Nyad telling “eight versions” of the same story. Here’s one rendition taken from a 2018 podcast that Nyad appeared on with writer and self-described "storytelling coach" Cal Fussman to promote Find a Way. (Warning: The story is extremely graphic.)

“She was made that day into the SS officers' little concubine,” Nyad said in the podcast. “For the next two-and-a-half years until the resistance saved all the people at that particular camp, she, every day, had oral sex, anal sex, intercourse, you name it, with these grown men. She was 3! And then 4! And then 5!”

The story ends with the “little concubine” getting adopted by a French couple and growing up to be a happy, functioning adult.

The point the Holocaust story is apparently supposed to make is that if a kid from Krakow overcame being an orphaned 3-year-old sex slave in a death camp, the rest of us should stop feeling sorry for ourselves about our lot in life.

Slosberg said that his in-laws were Holocaust survivors, and that the Dachau tale made his phoniness detector buzz even louder than a normal Nyad yarn. "I could never imagine my mother-in-law telling her story to a stranger," he said.

Slosberg was intrigued by her use of the phrase “little concubine,” and some quick research told him it came from Nabokov’s Lolita, while the tale Nyad offered “had echoes of Sophie’s Choice." Both references struck him as too convenient. He also remembered hearing that tattooing death camp prisoners was a practice limited to Auschwitz. And for all the minutiae in the death camp story, including Nyad’s descriptions of the background noises in the restaurant that night ("You could hear every fork clanging," she said), Nyad told the host that she can’t remember if she was in her “20s or 30s” when she encountered the Holocaust survivor. (In a 2017 appearance on the Brink of Midnight podcast, she retold the tale, but this time Nyad said she was "around 48, 49, 50" when she met the tattooed woman.)

Slosberg claims that for all his mistrust of everything Nyad says, even he felt queasy questioning this particular tale, given the subject matter.

“Who would make up a Holocaust story?” Slosberg asked.

But his distrust of Nyad overpowered any unease about truthering even this one. He confirmed via the U.S. Holocaust Museum that there was no tattooing at Dachau: “During the Holocaust, concentration camp prisoners received tattoos only at one location, the Auschwitz concentration camp complex,” reads an entry in the museum’s in-house encyclopedia.

Then he solicited an opinion on the rest of the story’s veracity from Dr. Barbara Distel, a former director of the Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site.

Among the historian’s determinations, which are included on a set of email correspondences between Dr. Distel and Slosberg posted on nyadfactcheck.com: “Dachau was a camp for men only,” she wrote. “There were never families or mothers with children.” Also: Polish prisoners were taken to death camps in Poland, not Germany. And Distel had never heard of any sexual child abuse at Dachau.

“The way she tells it is completely fictional,” Distel wrote.

The Hollywood public relations team now handling media for Nyad declined Defector's requests to answer questions about specific falsehoods, or about Slosberg on the record.

But Evan Morrison, a big presence in the marathon swimming community through his founding of the website marathonswimmers.org, subsequently contacted Defector, saying he had been asked by Nyad’s PR staff to make the call in support of Nyad.

He is not the likeliest advocate for the budding movie heroine. Morrison was among Nyad’s loudest doubters after her 2013 swim from Cuba. In a New York Times piece published shortly after Nyad landed in Florida, Morrison expressed disbelief that Nyad was claiming that only portions of the journey were videotaped. Marathoners pointed out that video from her previous, failed attempts at the Cuba swim showed Nyad holding on to her crew’s boat at points in the journey; if video showing the same thing popped up from the 2013 trip, that would immediately disqualify her from getting the swim verified as “unassisted,” as she’d hoped.

“If I was doing a swim that had never been done before and everyone thought impossible, I’d have a video camera on me continuously,” Morrison told the Times in 2013. Morrison around the same time gave quotes brimming with skepticism about Nyad’s Cuba swim to National Geographic magazine: “Is it possible she rested on the boat and she's not telling us?" Morrison asked.

Morrison has even posted information on his website calling into question the validity of Nyad's least-assailed swim, the 1975 Manhattan jaunt that first made her a household name in America. Here's a 2016 post from Morrison in which he has Morty Berger, founder of NYC Swim, the organization that oversaw Manhattan swims when Nyad made hers, saying his "interviews of [Nyad's] boat captain stated she touched/held onto the boat" while rounding the island.

Morrison now says, however, that he is ready to jump on board with Nyad. He told Defector he warmed up to the Cuba swim’s legitimacy after being presented with evidence from Nyad’s camp about the Florida Straits currents shifting in her favor late in the trip. He says he now believes that tidal shift could explain the radical increase in her pace for a stretch of several hours late in the trip.

Morrison admitted to still being gobsmacked by her fabulism fetish, but no longer let whatever character flaws Nyad has color his opinion of her athletic accomplishments. He said he now regards the Cuba swim as not only authentic but heroic, and worthy of a feature film.

“On one hand there’s statements that Diana has made, on the other hand there’s the swim in 2013. I think they’re different issues,” Morrison said. “I’m not trying to defend her falsely claiming to be in the Olympic trials or the first person to swim around Manhattan. I think we have to consider her body of work in context. She made these statements, and she did the [Cuba] swim. Both things are possible. There’s this film coming out, and the film is about the 2013 swim. The goal [of Slosberg] seems to be to convince everybody that the swim was a fraud and this film is based on fiction. In my opinion, the Cuba swim was real.”

Morrison posted what he called an “Open letter to the marathon swimming community” on his own website earlier this month, in the wake of the Los Angeles Times’ feature on Nyad. Though he didn’t mention Slosberg by name, it sure seemed like he was the letter's real target audience. In it, Morrison warned that anybody criticizing Nyad these days would hurt the sport by chasing away a “vast influx of new swimmers” who could be “inspired to dip their toes in the open water for the first time.”

“I believe the continued criticism of Diana no longer serves our community,” Morrison wrote, “at a time when potentially millions will be exposed to marathon swimming through a major motion picture.”

Morrison said he likes Slosberg personally. He let Slosburg launch the blog, Diana Nyad Factcheck Annex, on the same servers as his marathon swimming website. But their relationship has taken a sour turn just as a feature film about their favorite sport is about to hit the big screen. To Morrison, Slosberg has become as polarizing a figure in the marathon swimming world as Nyad.

“If you like her, you think he’s a bully,” he said. “If you don’t like Diana, you think he’s wonderful.”

Slosberg admitted to being shocked by what he regards as Morrison’s heel turn in joining Nyad’s camp just as the movie is about to be released. After years of hearing and reading Morrison hold Nyad accountable for untruths, he couldn’t understand how he’s now helping promote the film glorifying an accomplishment that Morrision always said he didn’t think really happened.

"I don't know what happened to Evan," he said.

Even just a couple minutes spent reading the material on nyadfactcheck.com will answer the question of whether Nyad has been making stuff up at a fantastical pace for decades. Whether this bizarre compulsion makes her worthy of the exposure Slosberg devotes to it is another question.

Slosberg said the mere fact that Annette Bening is playing her in a Hollywood feature film is proof enough she's fair game. But he also said Nyad’s fiction isn’t victimless.

Elaine Howley, an open-water swimmer and freelance journalist who covers the pastime, agrees. Howley said Nyad’s constant boasts about being the first woman to make the Manhattan swim, made when Nyad herself knows she wasn't, are particularly offensive.

“Whenever she says that, she erases some pretty extraordinary female swimmers,” Howley said. “I mean, you hear that one, and you go, ‘Really?’ It’s verifiable that others made it, that that swim was around long before she came on the scene. But it’s just the way she’s wired. She wants to be the center of attention and thinks that if she embellishes her record, it gets her more of the spotlight. And to some extent, it works. I mean, here we are talking about her!”

Nyad’s oft-made claim that she was the first to make the Cuba swim, an assertion repeated in press releases for her new movie, peeves more marathon swimmers than any of her other fabrications.

Nyad announced via a 2021 post on her Facebook page that Bening would be playing her on the big screen in a movie about how she became “the first (man or woman) to swim the crossing.” She got pilloried in the comments by folks who knew better.

“I don't know what is more sad,” wrote world-class open-water swimmer Grace van der Byl, “the fact that YOU Ms. Diana actually believe your own stories, Bless your heart. Or the fact that you have hoards [sic] of followers that believe your stories without any thought to validity.”

Van der Byl, like all marathon enthusiasts and Nyad herself, knows that Nyad wasn't the first. Walter Poenisch, a retired Ohio baker who swam from Cuba to Florida in 1978, is generally recognized as the real pioneer of that crossing. Nyad's treatment of Poenisch is the sin that the marathon swimming world isn't ready to forgive.

Poenisch dubbed his attempt a “Swim for Peace” and said his aim was improving relations between Cuba and the United States in the midst of the Cold War. It took more than a decade of lobbying the Cuban government before Poenisch's request to launch from Cuba's shores was sanctioned.

Poenisch announced he would swim with the aid of a shark cage and swimming fins. Neither a cage nor fins would be tolerated for an English Channel swim, but nobody had ever attempted this swim of the Florida Straits before, and those waters posed hazards the Channel doesn't. Poenisch said he'd found a group called the International Federation of Ocean Swimmers and Divers, which allowed a cage and fins in some swims, so he claimed he'd be swimming under that group's auspices.

Poenisch's effort did get noticed in high places in Havana. Fidel Castro met Poenisch on the beach as he started the journey, which began just after the swimmer’s 65th birthday.

Poenisch's act of so-called Speedo Diplomacy got no attention from the U.S. government, however, and only slight notice more from stateside newspapers. Nyad, who was still a media darling living off her Manhattan swim, was at the time planning her own Cuba crossing to launch right after Poenisch's. She had already sold the TV rights to the swim to NBC for a reported $10,000. She had also garnered $100,000 in sponsorships. From her conduct, it’s clear she saw Poenisch not as a peer worthy of support but as a rival that needed to be destroyed. She launched an aggressive and bizarrely bullying media blitz against the non-media savvy baker, inserting herself into whatever coverage Poenisch got in the months before he jumped in the water to trash him.

“A 64-year-old man has no business even trying such a demanding endeavor and he will surely fail,” Nyad told the Fort Lauderdale News on July 9, 1978, just days before his swim. She told the Palm Beach Post that Poenisch was a nothing more than "a stunt man." A report in the Miami Herald said that Nyad told the paper that Poenisch had cheated in previous swims by “using flotation devices and swimming aides in his marathon swims, and even holding onto the boat-towed shark cage.”

Poenisch completed his 128.8-mile trek from Cuba to Florida in a reported 34 hours, 15 minutes in July 1978. But when it was over, it seemed like the beating he'd taken from Nyad and her camp hurt him at least as much as all those hours in the open sea. When reporter Leo Suarez of the Palm Beach Post reached Poenisch just after he'd finished the swim that had been 10 years in the making, during what should have been the greatest moment of his life, there was no celebration. Instead, Poenisch was grumbling about how he was treated by Nyad. Suarez wrote: "'Why did she lie?' Poenisch said weakly, referring to Nyad. 'She lies. She lies.'"

Yet Nyad continued her attacks after Poenisch touched Florida. “He's not a legal marathon swimmer,” Nyad told The New York Times for its story the day after Poenisch finished his swim. “He does not swim by the rules. He's a gimmick. He's a cheat. In the world of sports, he's a cheat.”

The Times piece also had Richard A. Mullins, who was identified as “the director of public relations for the International Swimming Hall of Fame in Fort Lauderdale,” saying that he personally witnessed Poenisch cheat on previous swims. “I don't accept for one minute that he's done it,” Mullins told the Times. “He doesn't have any credibility as a marathon swimmer.”

The story did not mention that Mullins was also a member of Nyad’s crew for her own imminent attempt at a Cuba swim, or that the ISHOF had launched Nyad’s career.

Just days after Poenisch finished his swim from Havana, Nyad tried to make the same trip, also using a shark cage but without fins. But Nyad stopped swimming after 42 hours in the water, still a reported 80 miles away from Florida when she gave up.

Poenisch sued Nyad, Mullins, and the ISHOF for slander. The suit was settled in 1983 when she agreed to pay him a reported $5,000 (out of an overall payment of $15,000 from the three defendants) and retracted her accusations that he’d cheated. That settlement, however, did not include an apology to Poenisch.

Poenisch died in 2000. Nyad posthumously apologized to him, but only after her 2013 swim. "I wish I could look up to the sky and tell Walter that I am profusely sorry," Nyad told the Wall Street Journal.

Poenisch’s survivors didn’t buy Nyad’s babyface turn. A story published by the Columbus, Ohio news magazine 614 had Faye Poenisch, the swimmer’s widow, saying that Nyad’s use of the media to attack him cost him sponsors, credibility, and more.

“As far as I’m concerned,” Faye Poenisch told the magazine, “she helped destroy my husband’s life.”

Poenisch was enshrined into the International Swimming Hall of Fame in 2017. Nyad has been denied entry into the Hall's main pool of swimmers. In 2002, she was given the ISHOF's Al Schoenfield Media Award for years of "dramatic storytelling" and "a charismatic stage presence."

Wigo, ISHOF’s former director, says Nyad has in recent years personally and unsuccessfully lobbied the organization hard for her own induction in the swimmer's wing. Nyad's bio on the ISHOF website, put there for the Schoenfield nod, has been edited over the years to remove inaccuracies. A line that said she was a state champion in the 200-yard backstroke in high school, for example, is no longer visible in her ISHOF bio. Nyadfactcheck.com's records from the state championship meets indicate that there was no 200-yard backstroke. She had, in fact, won a 100-yard backstroke title, which was in the bio. For any other world-renowned swimmer, adding one more high school state championship to the résumé would be viewed as too ticky-tack to be anything other than an honest mistake, but Nyad's past portends yet another attempt to steal valor.

Nyad's behavior out of the water, Wigo said, has helped keep her from being inducted.

“What she did to Walter Poenisch is unforgivable,” Wigo said. “How can you put somebody in the Hall of Fame who is so unethical?”

That’s not the only rejection Nyad has faced because of alleged ethical breaches. Susan Moroney, an Australian marathoner, successfully completed the Cuba swim in 1997, using a shark cage like Poenisch, but no fins. Nyad’s 2013 trek was her fifth attempt, and was done without a shark cage. Nyad is the first person to claim to have completed the swim cageless and finless.

However, Nyad has had trouble getting any recognized swimming sanctioning body to sign off on the legitimacy of her swim, despite the aggressive efforts of Nyad and her movie’s producers. Earlier this month, the World Open Water Swimming Association (WOWSA), a sanctioning body for solo endurance swims, announced that Nyad had requested that the board reconsider ratifying her 2013 Cuba crossing. The group said the producers of Nyad had also asked.

The WOWSA board, however, came out strongly against the requested ratification. In an extremely harsh statement released Sept. 9 explaining the rejection, the WOWSA board said Nyad and her camp had told them "that the swim had been completed in conformity with rules and procedures promulgated by an organization, Florida Straits Open Water Swimming Association (FSOWSA).” However, during the WOWSA investigation prompted by Nyad et al, the board said the “existence of [FSOWSA] at the time of the swim, or at any point, could not be verified.”

“We found a document with rules that seemed to have been retroactively dated, and there were inconsistent statements from crew members,” the statement read. “In light of these factors, we’ve chosen to preserve the sport’s integrity by denying the ratification of the swim.”

Slosberg was not invited to and did not attend any advance screenings of Nyad. I asked him if he will see the film when it hits theaters—the premiere is scheduled for Oct. 20. He said he hasn't decided yet. His mind is made up, however, that she didn't finish the Cuba swim legitimately, and he doesn't want to pay money to be told she did.

At the end of September, Slosberg copied all the files on his blog that had been hosted by Morrison's site, saying he didn't trust that “this new incarnation” of Morrison wouldn't block internet surfers or even him from accessing the anti-Nyad arsenal he'd put so many years into accruing.

“We are no longer compatible,” Slosberg said.

The site has left a mark. Nyad's dishonesty is no longer questioned by the majority of marathon swimmers. It's accepted.

Virtually every preview of Nyad so far has had at least some reference to the real-world Nyad’s inability to stick to the facts. The Los Angeles Times devoted lots of column inches in its recent Nyad profile to accusations that she's a fraud, including some from Slosberg, who the paper said "has waged a particularly intense and, at times, bitterly personal campaign to highlight questions about Nyad’s claims."

Not coincidentally, the people who actually made the film speak about it differently than when the project was first announced. The original press release for Nyad said the movie follows "the fantastic true story of swimmer Diana Nyad, who ... defied the odds to become the first person to complete the 110-mile journey from Cuba to Florida."

But in an interview published in August by Vanity Fair, director Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi backed away from that characterization, and while doing so seemed as flummoxed as Nyad by the concept of a "true story."

"We don't say, ‘It’s based on a true story.’ We don't say, ‘It is a true story.' But it is a true story," the director said. "It’s about this idea of truth.”