Spare me your analytics, and your short-attention-span-theatre I-only-remember-what-I-stream clucks. Save your explanations of impact, comparisons with contemporary or historical players or comparative surveys of black ink and gray ink on Baseball Reference. Dick Allen is a Hall of Famer because of the picture. It appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated in 1972, and shows Allen, resplendent in mutton-chop sideburns and a Nixon-era White Sox uniform, casually hanging an unfiltered heater off his lip while juggling three baseballs in the dugout. If he had Willie Montañez's numbers, he still enters Cooperstown for this alone.

Dick Allen, put simply, is exactly what baseball most craves today—a walking, talking, smoking, juggling, hitting, singing ziggurat of cool. He did stuff in the biggest, boldest ways, and it isn't really his fault that he did them when big and bold were less in fashion among ballplayers than it is now. Allen didn't get into the Hall in its yearly general elections not because of anything he didn’t do on the field but because he was marked with what oldey-timey-and-mostly-whitey sportswriters of the era liked to refer as "attitude." At the time, "attitude" could mean anything not specifically Gary Cooper/silent type/modest sideburns/middle American; in Allen’s case, it meant more or less what you’d expect it to mean when applied to a black All-Star who knew his talent and his worth. Allen got the nod for Cooperstown yesterday, from the grandiosely yet redundantly named Classic Baseball Era Committee vote.

His baseball accomplishments aside, it is the photo that explains it all. Sure, those wise old nostalgics (and I know several of them, so I know it's true) on the committee surely talked about all the usual ball stuff, and there’s plenty to talk about there. But in their souls, they knew this had to be done, even though they hadn't done it in past elections. More than that, it needed to be done in the aftermath of Juan Soto's elephantine contract because 51 years ago, Allen was the highest paid player in baseball with an unfathomably extravagant three-year, $750,000 contract. Money knows money, even if it's only 3.4 percent of Soto's after inflation adjustment.

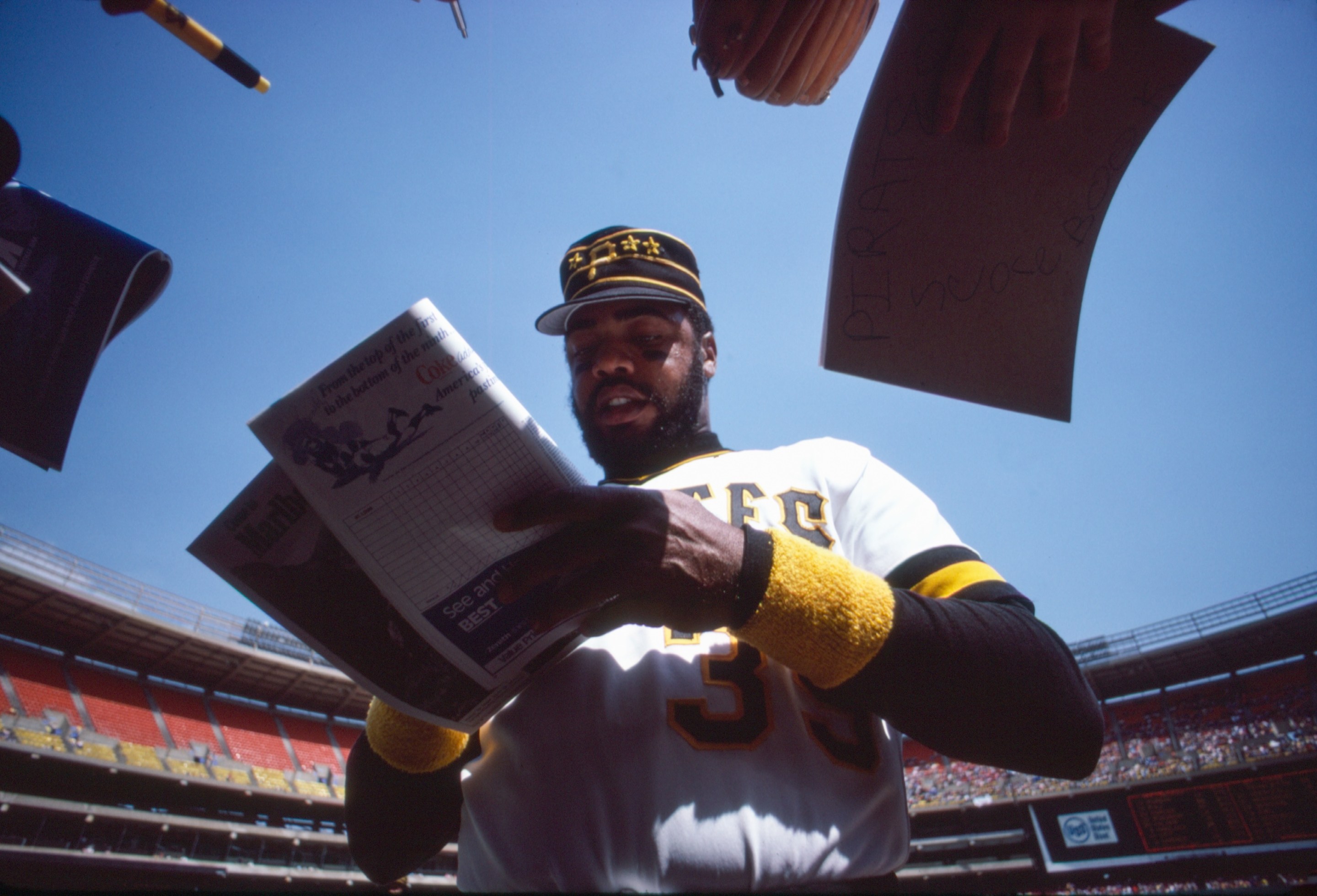

Do you know who else got into the Hall at the same time and for largely the same reason? Dave Parker, a.k.a. Cobra, another bigger-than-bigger-than-life 1970s superstar. Parker was more streamlined than Aaron Judge and looked considerably more badass in those Pirates gold unis and conductor's hats as he turned on an ill-aimed fastball and sent it toward the ionosphere. That’s no knock on Judge; basically no ballplayer of any era has ever looked cooler while doing that. There are also dozens of photos of Parker sliding into bases and the people tasked with guarding them, all of which serve as proof that Parker played hardball the hardest way and was still cool in motion, even if he couldn't necessarily juggle.

We'll not fuss about how long it took for baseball to figure out how to do right by Allen and Parker, except to note that Allen died before the voters realized it. Chasing history's ghosts is a particularly useless pursuit. But Allen and Parker define what baseball wishes it had more of at its current low cultural ebb—the glow of import. Allen and Parker filled clubhouses and dugouts and lineup cards simply by being there, early Ohtani-level characters in a sport which at the time only knew Ruth and DiMaggio. They were the logical inheritors of the Negro League talent influx that electrified baseball while belatedly integrating it, and were the vanguard of the first generation to outwardly show how cool baseball could be.

These are all stylistic points, to be sure, and the Hall of Fame has struggled to factor that into an honorific that has never fully decided if it is a museum or a way to reward friends and punish enemies. But at a time when baseball is being condemned as the cultural enemy of style, the regret for the sport is that they didn't have more Allens and Parkers to go along with the excellent but more self-effacing stars of the last five decades. Besides, while one can be stylish and one can be great, the finest Hall of Famers really ought to be both. That neither of these two was properly appreciated in either their moment or their turns through the voting process—that they were instead carped at in the first and brushed off in the second—makes yearning for more of their kind now more delightful. Even if tobacco is now fully on the carcinogenically uncool list.

But let's be clear here, as we acknowledge the changing mores of smoking: Any player who is willing to juggle before a game with a blunt hanging off his lower lip is getting at least one vote. Even if he happens to be (gasp/choke/wheeze/cough uncontrollably) a Los Angeles Angel.