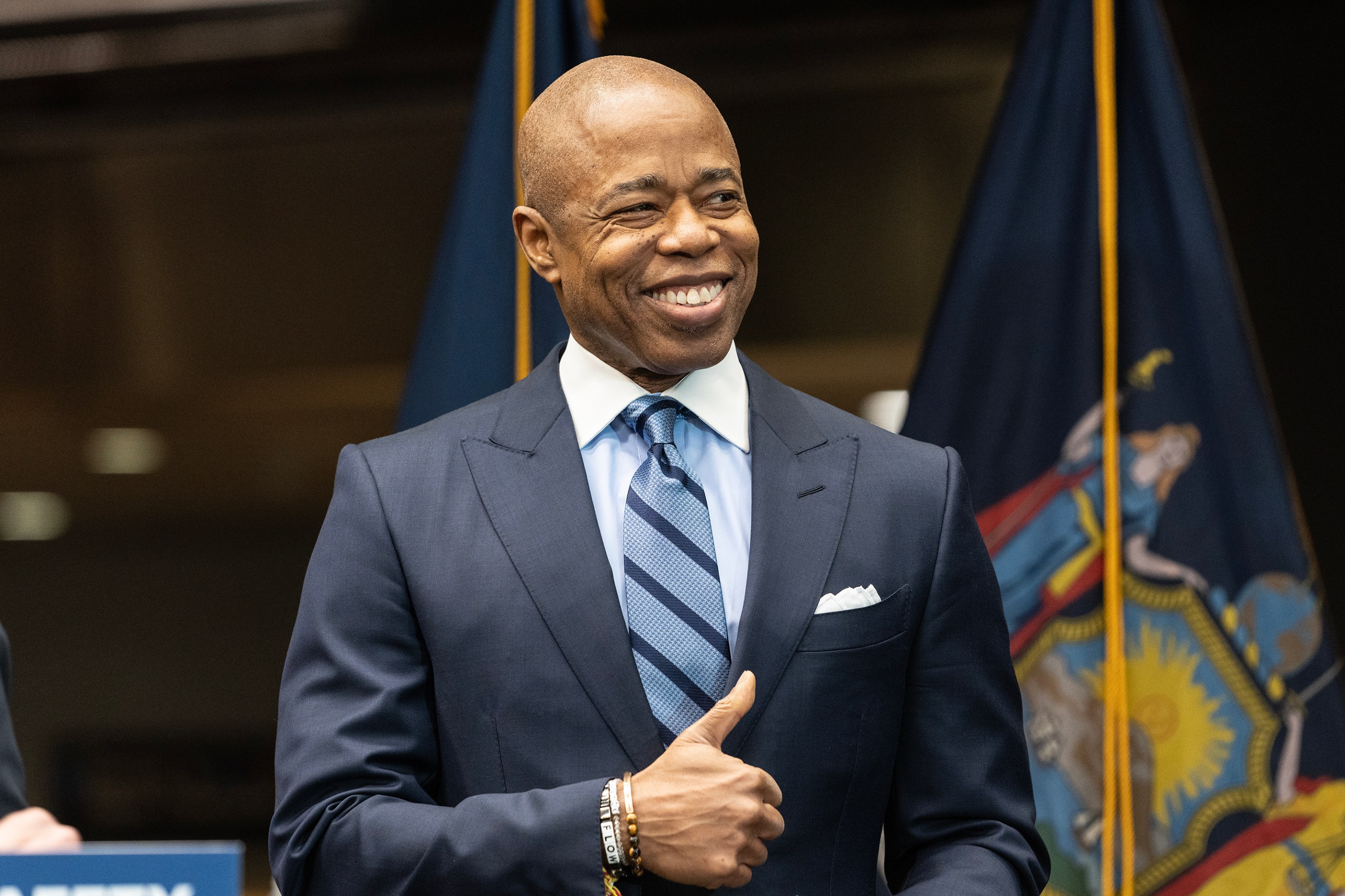

"We are going to make sure, based on our numbers, hit ratio, false hit, we're going to do our data," New York City Mayor Eric Adams said earlier this month when introducing the AI-aided scanners his administration plans to test in some of the city's subway stations. "What I'm hearing from my corporations, from my hospitals, from others, they're saying this is living up to our expectation."

As with many things Adams says, this is both extremely confusing and provably false. As Felipe De La Hoz wrote at Hell Gate, the devices he was talking about had already been tested at a hospital in the Bronx, where they lived up to expectations in the sense that they "generated outlandishly high numbers of false positives." They beeped roughly once for every four people that walked through them over the course of seven months, more or less at random. Over 85 percent of those were false positives; De La Hoz reports that "0.57 percent, were determined to be a non-law enforcement person carrying either a knife, a gun, or a threat type labeled only 'other.'" Over the course of that pilot program the sensors not only did not become more accurate, they became worse in the ways that borked AI stuff tends to compound its borkage over time; in the pilot's final month, the false-positive rate was 95 percent. As recently as last month, the CEO of the company that makes these scanners said that "subways in particular are not a place that we think is a good use-case for us."

But this might be more about Our Expectation than anything else. Adams, who was out of ideas on his first day in office and is fad-prone even by the sky-high standards of big city mayors, may well believe that AI is or will very soon be magic. A wide-ish spectrum of powerful weirdos, from libertarian economists to people whose business depends upon those promises to Elon Musk, claim to. But also the fact that these devices do not actually work very well and can't work under these specific conditions is immaterial; so is the fact that the Adams administration's new and vigorously hyped MyCity Chatbot, which is designed to answer questions about opening and operating a small business in New York and runs on Microsoft's Azure AI, was giving powerfully and actionably incorrect answers from the jump, and stayed doing so after reporting by The City and The Markup revealed how busted it was.

"While the bot previously included a note saying it 'may occasionally produce incorrect, harmful, or biased content,'" a subsequent joint report revealed, "the page now more prominently describes the bot as 'a beta product' that may provide 'inaccurate or incomplete' responses to queries." A warning on the page tells users not to use the bot for professional advice, and to double-check all of its answers against other resources. When a Markup reporter asked the bot whether it could be used for professional advice, it replied in the affirmative.

This is bad, but it is not important. It would naturally be very important to a member of the public who was using this public-facing AI chatbot to get advice—or using TurboTax's or H&R Block's AI chatbots on their taxes, or just trying to find reliable information amid the AI-generated sludge shitting up the internet. But the bet that everyone involved has made is that it doesn't really matter whether it works, which is sort of the same thing as saying that the people being pushed into using it don't really matter, either. That has generally not been a position that governments or businesses have been comfortable taking quite so explicitly in the past; people tend to find it insulting. But if you can get past that, there's a whole lot of future out there for the taking. Or, in Adams's case, for standing next to while making some remarks.

At this stage in this increasingly ubiquitous and increasingly janky technology's strange simultaneous ascent and descent, AI is far more successful as a brand or symbol than it is as any actual useful thing. A technology this broken would not be something that government, for instance, would obviously want to use, given the extent to which a government's credibility has traditionally been understood to depend upon being trustworthy and consistent, and the extent to which AI is currently unable to be either of those things. But if you didn't really care about that, then you wouldn't really care about that.

If AI has yet to be put to any kind of positive social use, it is nevertheless a brand associated with a certain type of rich person and their ambitions, and so with a specific contemporary vision of success. And in that sense it is very much the sort of thing that would appeal to a government—or a business, or a bubbleheaded executive anxious to seem current—that was more concerned with appearing forward-looking, futuristic, and upscale than it was with providing quality service. That these products absolutely do not work and are not really improving would not mean very much to a government—or business, or executive bubblehead—that wasn't concerned about any of that. That sort of client would care more about branding and spectacle, and in that sense AI delivers even as it repeatedly fails to actually deliver in any other sense.

This raises some obvious questions about what any of this is actually for, but is also familiar. The reigning capitalists of Silicon Valley are very plainly out of ideas, but not at all short on money or prescription amphetamines, and so they have stayed very busy. AI is both on the continuum of the other Silicon Valley fads that have busted in recent years due to their unworkability or lack of appeal to normal people or both—think of the Metaverse, or the liberatory implications of cryptocurrencies—and that dippy program's logical endpoint.

The most general description of AI as it exists now—which is as an array of expensive, resource-intensive, environmentally disastrous products which have no apparent socially useful use cases, no discernible road to profitability, and do not work—is something like the apotheosis of Silicon Valley vacancy. That the most highly touted public manifestation of this technology is a predictive text model that runs more or less entirely on theft, generates language that is both grandiose and anodyne and defined by its many weird lies, and also seems to be getting dumber is, among other things, kind of "on the nose." But it is all like this, hack bits that barely play as satire; billions of dollars and millions of hours of labor have created a computer that can't do math. These technologies both reflect the bankruptcy of the culture that produced them and perform it.

It is also perfectly Silicon Valley that all this is so unimportant to both the rich people invested in it and the fatuous and irresponsible politicians and institutions eager to align with them. There are AI technologies in development whose most obvious and arguably only use case is "doing crime," and there is the grim and scuzzy use to which existing AI technologies are already being put on YouTube and in the international shitscape of spam ads and pornography. Even potentially useful applications are dubious and buried in preposterous, reckless hype. "I feel like a crazy person every time I read glossy pieces about AI 'shaking up' industries only for the substance of the story to be 'we use a coding copilot and our HR team uses it to generate emails,'" Ed Zitron writes in his newsletter. "I feel like I'm going insane when I read about the billions of dollars being sunk into data centers, or another headline about how AI will change everything that is mostly made up of the reporter guessing what it could do."

Zitron believes that AI is a bubble, and that there is fundamentally not enough data available—even if OpenAI, Google, Microsoft and the other behemoths behind the technology continue their heedless and so-far unpunished Supermarket Sweep run through the world's extant intellectual property—to make these products usable enough to be functional, let alone profitable. That bubble's collapse could prove disastrous for an industry so deliriously high on its own supply that it eagerly and fulsomely committed to AI without bothering to figure out what it was committing to, and so seems happy to push these janky products out before they've figured out how to make them work. "If businesses don't adopt AI at scale—not experimentally, but at the core of their operations," Zitron writes, "the revenue is simply not there to sustain the hype."

If there is a reason to question that skepticism, it has nothing to do with any existing AI service I've encountered; they all make me very sad, and even AI acolytes seem to have lost their taste for the dead-eyed algorithmic doggerel and implausibly bosomy cartoon waifus that once so delighted them. The question, which opens onto awful new worlds of dread and possibility, is whether any of that means anything. There is enough money and ambition behind all this stuff, and a sufficiently uncommitted collection of institutions standing between it and everyone else, that AI could become even more ubiquitous even if never actually works. It does not have to be good enough to replace human labor to replace human labor; the people making those decisions just have to go on deciding that it doesn't matter.

"This technology is coming whether we like it or not," Eric Adams said in early April. This time he was announcing that self-driving cars, another technology pushed out into the world despite manifest and obvious limitations, would be allowed on New York City streets. Again, his statement is both confusing and untrue. None of this has to happen, or would happen on its own. Capitalists can push it forward and institutions can get out of their way, but at some point people will either take what they're being offered, or refuse it.