The first thing I watched in the pandemic was more or less the entirety of Seven Up! Children ambushed by Michael Apted every seven years for the rest of their lives: What could be better? I watched it swathed in duvets and gorged on waffles, a food I basically haven’t eaten since, feeling so remote from the world that I keep wanting to add snow into the remembered California landscape. But who needed the outside world? I had Seven Up! to take me deep inside what it meant to get to know someone, the collating of tiny gestures, the way words are formed, heads tilted, while at the same time situating them within the broader world, seeing the costs of the way they existed, borne both by them and by others.

The way I remember it is that I watched Seven Up! and then I watched the second season of Formula 1: Drive To Survive. But the internet tells me that Season 2 of Drive to Survive was released a couple of weeks before my office shut down, and I feel like I would have watched it as soon as it came out, because I was one of those indeterminate-number-guarded-closely-in-Netflix’s proprietary-data-bank of people who watched Season 1 of Drive to Survive and loved it with a fiery burning passion.

Some of what made it so lovable was just a matter of the people who made it doing their jobs well, of capturing things that managed to be both irreducibly human and totally unexpected—I can still remember early in the first season, before we had even been properly introduced to Haas driver Romain Grosjean, two McLaren team members making fun of him, and the way it managed to perfectly reproduce the dynamics of the kind of mean-spirited conversation held every day of the week in an office somewhere.

But also Mercedes and Ferrari, the top two Formula 1 teams at the time, didn’t participate in that first season. Which meant that whatever story the series was going to tell it wasn’t going to be one of ultimate success. This made the show better—a story about who was going to win the Constructors’ Championship might well have skipped out on Daniel Ricciardo’s singing and would have been the weaker for it. To the extent that first season had a storyline, it was Ricciardo as the good guy driven out of Red Bull by the anointing of Max Verstappen; the singing reminded you that Ricciardo was just another jerk-dummy. Sports, unlike almost anything else in the world taking place in real time, gives us a definite ending, an answer to the question of who was better (on that particular day, under those particular conditions); our hunger for that answer exerts a gravitational force that distorts our perceptions, that leaves us with, say, the sanitized version of Kobe Bryant that continues to astonish me today. The details Drive to Survive left in made it easier, or at least made it feel easier, to see the outcomes whole.

Around the same time I watched a pretty similar series on the Mumbai Indians of the Indian Premier League—it was good, worth watching if, like me, you can’t get enough of this stuff. But it didn’t have that sticky quality; I didn’t imprint on it. I didn’t start watching cricket. The series mostly wanted to tell me about how the Indians fared that season; it wasn’t, in the end, extraneous enough to grab me. You can’t get someone to care about outcomes by focusing on outcomes.

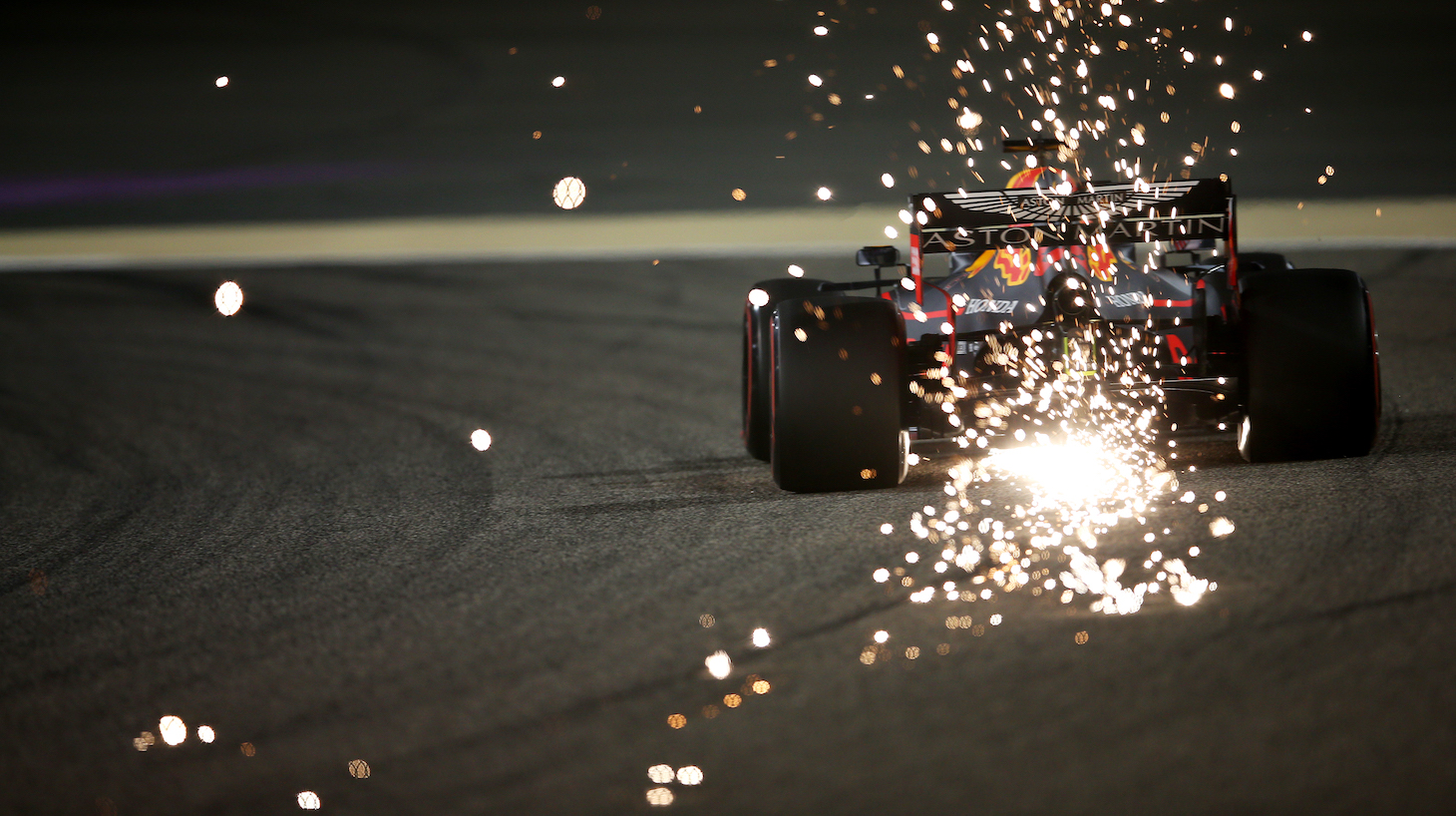

I did start watching the actual F1 races. “Isn’t it boring?” my father said. “They’re just going around and around.” He’s not wrong—although the cars are going unfathomably fast and minuscule mistakes by the drivers have insane consequences, the middle of the average race just looks like a bunch of guys driving. Because they’re all going that fast, you can’t see the speed. It still isn’t boring. The things I like about it: being up at such a virtuous hour to do something totally pointless, the announcers’ turns of phrase, the sudoku strategy pieces—which tires to use, when to pit. But also, of course, having seen Season 1, I watched the races partly because I wanted to know what happened next, what became of all these characters I was already invested in.

Having watched the races, knowing the outcome, did not in any way diminish my desire to see Season 2. Again, this was not because the reality-show version of the sport promised me a narrative unclouded by the million little details that come with watching something in real time. I didn’t need professional editing to tell me that Bratz doll lookalike Pierre Gasly finally getting a podium place after being abruptly demoted from the Red Bull team was a stirring come-from-behind victory; I’ve watched sports movies before. And although I didn’t mind the thought of watching it again, I also didn’t have a particular interest in seeing it in the mode of the championship compilation videos that they used to sell in my youth where they set the highlights of the Lakers season to music. Nor did I want to watch it because I foresaw added drama—a lot of the most aggressively catty behavior in Formula 1 takes place out in the open. What I wanted was the opposite; I wanted the races cut down to human level, even if I had no intention of relinquishing my pre-existing prejudices or of ever again calling Red Bull team principal Christian Horner anything other than “the villainous Christian Horner.”

After all, we process the meaning of sports and attach emotion to it without any assistance whatsoever. When I was about seven and visiting my father’s hometown of Rochester, New York, I saw the Triple-A Red Wings play the visiting Richmond Braves, and was startled and dismayed by the unanimity with which the people around me booed the Braves, so I developed a passionate if shallow commitment to their success. My favorite teacher rooted for the Yankees and Notre Dame football because when he was a kid he liked winners, which is more or less the same thing.

And neither of these are stories about kids ignoring the healthful raw vegetables of sports in favor of the cotton candy of processed narrative. There is no raw matter when it comes to pro sports. Even if you set aside as ahistorical the idea of a lone man in a garage inventing basketball, the current rules and operations of major sports leagues are the product of rich men deciding how to maximize their investments. The version you see on the field is already artificially sculpted. Sports stop being pure the moment anyone starts keeping score. This isn’t a bad thing, more an understanding that there’s no true essence there to corrupt.

Which is not to say that the reality-show version is somehow purer. Daniel Ricciardo was, after all, paid for his participation in the first season of Drive to Survive, including being given a cut of the profits, separate and apart from whatever publicity benefits he accrued—other people presumably were too, without being involved in lawsuits where it was made public. But the reality television version, even when exaggerated or distorted, holds the potential to broaden the lens through which we watch the sports, to teach us to see things we otherwise would have missed.

Sports does its best to carve out an area of reality in which we always know who won and who lost. That’s the point. (Don’t try to talk to me about tie games.) What the best sports reality shows do is let the murky gray space of our shared reality back into the sharp technicolor of the average sports broadcast; they un-arc the narrative. They give us a thousand versions of the cat on the field. At their best they are more Ron Luciano than Roger Kahn. This does not make them more honest; it does not even necessarily make them better art. At most, maybe, it allows us to bring more of ourselves to the act of watching sports. At the very least it gives us another chance to point and laugh.