There is no man whose name has become so synonymous with a thankless job than Sisyphus, perhaps the person most responsible for keeping large boulders, and the pushing of them, in the cultural conversation. What I wouldn't give to see him take on the large boulder the size of a small boulder! It was inevitable that a genus of dung beetles—the insects famous for rolling enormous balls of excrement over long distances—would be named Sisyphus.

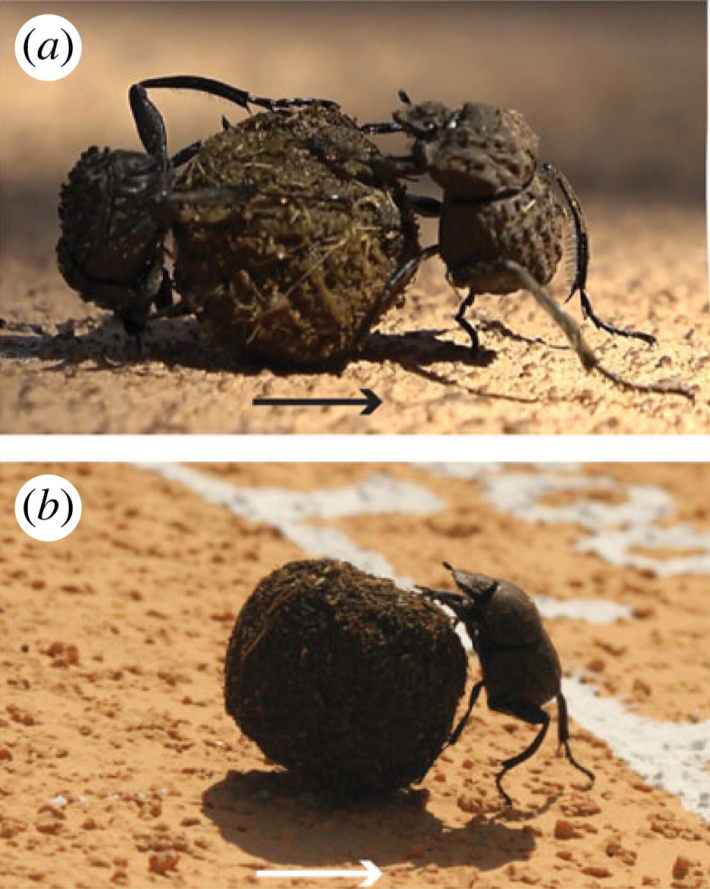

The quintessential image of a dung beetle at work also mirrors the myth: a lone male beetle pushing a smelly sphere with enormous difficulty and no assistance. But in certain species, dung can spark a collaboration between a male and female. In some cases, females will walk behind their dung-rolling male. In others, the female hitchhikes on a ball of dung rolled by the male, an act that is not necessarily helpful but certainly a choice. Sometimes, males and females dig together to bury their dung or even roll the dung together. The French entomologist Jean-Henri Fabre included an image of such a collaboration, in his 1921 work Fabre's Book of Insects, accompanied by the caption, "Sometimes the Scarab seems to enter into partnership with a friend." Edward Julius Detmold's illustration, seen above, depicts two lustrous black beetles maneuvering a brown sphere over a small dune of dirt, speckled with pink flowers. It is an exceptionally tasteful painting of excrement, the kind of art one might frame and hang in a bathroom to gaze upon and dutifully ponder while fashioning dung balls of your very own.

Dung beetles must abscond with their prize in a straight path to ensure it is not stolen by competitors, and to maximize the distance taken with each step. But a straight path is not always easy for a creature as small as a beetle, for whom elephant footprints, small rocks, and shrubs can be larger-than-life obstacles. In another book, Fabre actually described a pair of spider dung beetles of the species Sisyphus schaefferi, who, in an attempt to relocate a dung ball away from a larger heap, surmounted innumerable obstacles in order to keep rolling in a straight line.

Fabre's observation raised several questions about this partnership. When it came to dung-rolling, were two spider dung beetles better than one? And how did they coordinate such a thing, rolling a ball so big that might block their sight of both the other beetle and their path ahead? This month a paper published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B came to the heartwarming conclusion that spider dung beetles do coordinate while dung-rolling, and that this partnership helps them overcome obstacles more quickly when they work together.

The researchers studied the South African Sisyphus fasciculatus and S. schaefferi, the beetles observed by Fabre. Both dung beetle species live in woodlands, meaning they often run up against plants and other debris blocking their path. They collected the beetles from the wild, using traps baited with about half a soda can's worth of fresh cow dung.

Once they had the bugs in hand, they released about 50 beetles into a plastic container filled with soil and a cabbage-sized lump of dung, enticing the beetles to pair off and begin scooping out balls. Each pair self-sorted into a male "dragger" beetle and a female "pusher" beetle, and together they would actively roll the ball away. The researchers then put these pairs to the test over a series of arenas of increasing difficulty.

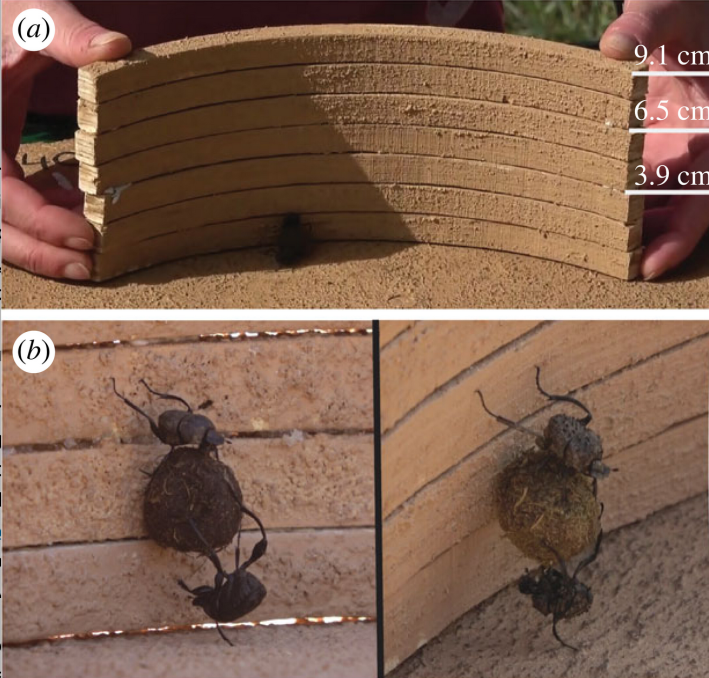

On flat ground, the beetles rolling in duos did no better than the solo rollers. But when obstacles came into play, couple privilege allowed the male-and-female pairs to surge ahead of the pack. The researchers placed the beetles at the center of concentric circular plywood rings, stacking them at various heights up to 3.5 inches tall. When up against a ring, the male would begin to climb the wall and drag the ball, which the female would be lifting up with her legs from a headstand position, allowing the male to pull the ball up and over the wall. When males lost their grip in the climb, females also often prevented their partner's fall. In solo tests, lone males did manage to drag the ball over the highest obstacle, but far fewer beetles even made the attempt.

Although partnership clearly presented the beetles with the easiest route over the wall, the researchers found the female "seemed to provide assistance only when critically needed." To the male, this might seem an uneven partnership, even if it is far more useful than offers from females of other species to ride the dung ball and further weigh him down. But poor Sisyphus—the two-legged one—didn't even have a companion during his unending exertions. Perhaps he would have been happy to carry a heavier boulder if it meant he would have a buddy to spend his days with. Perhaps they could talk of boulders both large and small, or perhaps they could trudge up the hill in peaceable silence, thinking of how much worse things would be if he instead was forced to push a fragrant boulder of dung up that hill. But in the case of the other Sisyphus, whether or not a beetle can experience happiness, he can lean on a pal to help roll his ball up a hill, at least in times of critical need.