Standing in the courtyard of a New York hotel, Sid Abbruzzi—the septuagenarian surf and skate legend from Newport, Rhode Island—held his phone to his ear while I asked him over a Zoom call what he thought about his anti-capitalist hero status. This July, directors the Kinnane Brothers released Water Brother, a feature documentary about Abbruzzi’s life.The film uses archival footage from 1969 to today to catalog Abbruzzi’s time as a rarified Newport local and owner of beloved surf shop, Water Brothers. The shop—a lighthouse to young skaters and surfers for the 50 years it was around—finally succumbed to destruction by developers in 2024, despite decades of pushback, hijinks, and punk vigor that had long kept the place alive. Water Brother, the documentary, tells it all.

“We were just free spirits,” Abbruzzi said of the 50 years that he ran the shop, at one point building an unsanctioned skate ramp in the parking lot and signing the local skater kids up for the Boy Scouts just to get insurance coverage. “All we wanted to do was skate and surf. In the film, [Johnny Leys says], ‘He was the worst businessman I’ve ever met.’ And that’s true.” During the storied history of Abbruzzi’s shop in Rhode Island, Abbruzzi earned the nickname the “Giveaway Butcher” because he was so motivated to get kids into surfing and skating that he was constantly giving gear away. And anyone who skates or surfs knows that the gear is not cheap. “I never got into this to be a businessman, to become a Ron Jon surf shop, to be any of that stuff,” Abbruzzi said. “And I'm glad I never did. Just to keep my head above water has been good enough for me.”

The documentary tracks an all-too-common theme: an anti-establishment owner that draws in a ragtag but devoted crowd of misfits, then spends his life pushing back against selling out to those who want a piece of the impossible-to-scale-or-capture pie. In Newport, a place now rarely associated with anything punk, there was a robust local townie scene before the city became a place where celebrities like Jay Leno kept their second homes. In interviews with Tony Hawk, Shepard Fairey, Peter Mel, Selema Masekela, and a dozen others, the film presents Abbruzzi as a beacon for the surfing community along Rhode Island’s few and famous surf breaks. How he kept it up for as long as he did—even petitioning and winning against more development that would affect a beloved surf break called Ruggles—is a sign of Abbruzzi’s dedication to the area in which he grew up.

“When Covid hit, it was a big game-changer. I would say 75 to 80 percent of the surfers [at First and Second Beach] are now from out of town. They drive a half an hour to two hours every day to surf the beach at Newport,” Abbruzzi explained of the state of affairs at Newport these days. “This town has gotten so expensive that it wasn't like it was in the ‘90s when people lived at home, or they could afford to rent an apartment. Nowadays, you've got to be a wealthy out-of-towner to buy property here, and a lot of people have moved on that would've possibly been still surfing in this area. You could [now] pull into the Second Beach parking lot and not know a soul, with a hundred people out.”

This change in the population is part of the reason that Abbruzzi kept at it with his business partner, Rick Weibust, for all those years, despite the signs that the beach town was really changing. “Puma came and approached us on a big deal, and a bunch of other companies sort of like that came, but it was never right. It never felt right and it was never right,” Abbruzzi said of his desire to not sell out to a corporation and go big with his brand. “And I'm glad we never did that.” When the movie about his life was ready to go on the road, Abbruzzi said they didn’t even have the forethought to bring enough Water Brothers merch to sell at screenings. “We've never been online in our lives,” Abbruzzi said about the store’s charmingly retro lack of e-commerce. With the success of the film, that is about to change.

When the building that Water Brothers lived in for a good portion of its history was bought and destroyed in order to make way for more short-term lodging—captured in a tragic scene at the end of the film—it seemed that Water Brothers as Abbruzzi knew it had come to an end. Plenty of people came to him and said the film could be the thing that breaks Water Brothers into the next phase of its history. “This movie is like the Dogtown and Z-Boys movie,” Abbruzzi said people have been telling him. "'You guys can crush it.' Well, we're not interested in that. We're interested in everybody enjoying the film, and if opportunities happen, they happen.” And for now, at least, business is back in a small way: Jerry Kirby, an executive producer on the film, bought the building next door to the former Water Brothers for Abbruzzi to run a facsimile of the shop—pop-up style—whenever he’s in town and feeling up for it.

At one point in the film, Abbruzzi mentions going to New Jersey in the early ‘70s to buy up surfboards to sell at the shop. With so much attention being paid to waves like Teahupo’o in Tahiti and Jaws in Hawaii, lesser-known and lesser-respected spots in East Coast locales like Rhode Island and New Jersey often get overlooked or underestimated. As Abbruzzi put it, his early experiences trying to surf in New Jersey were a bust: “It was cold and flat as a lake.”

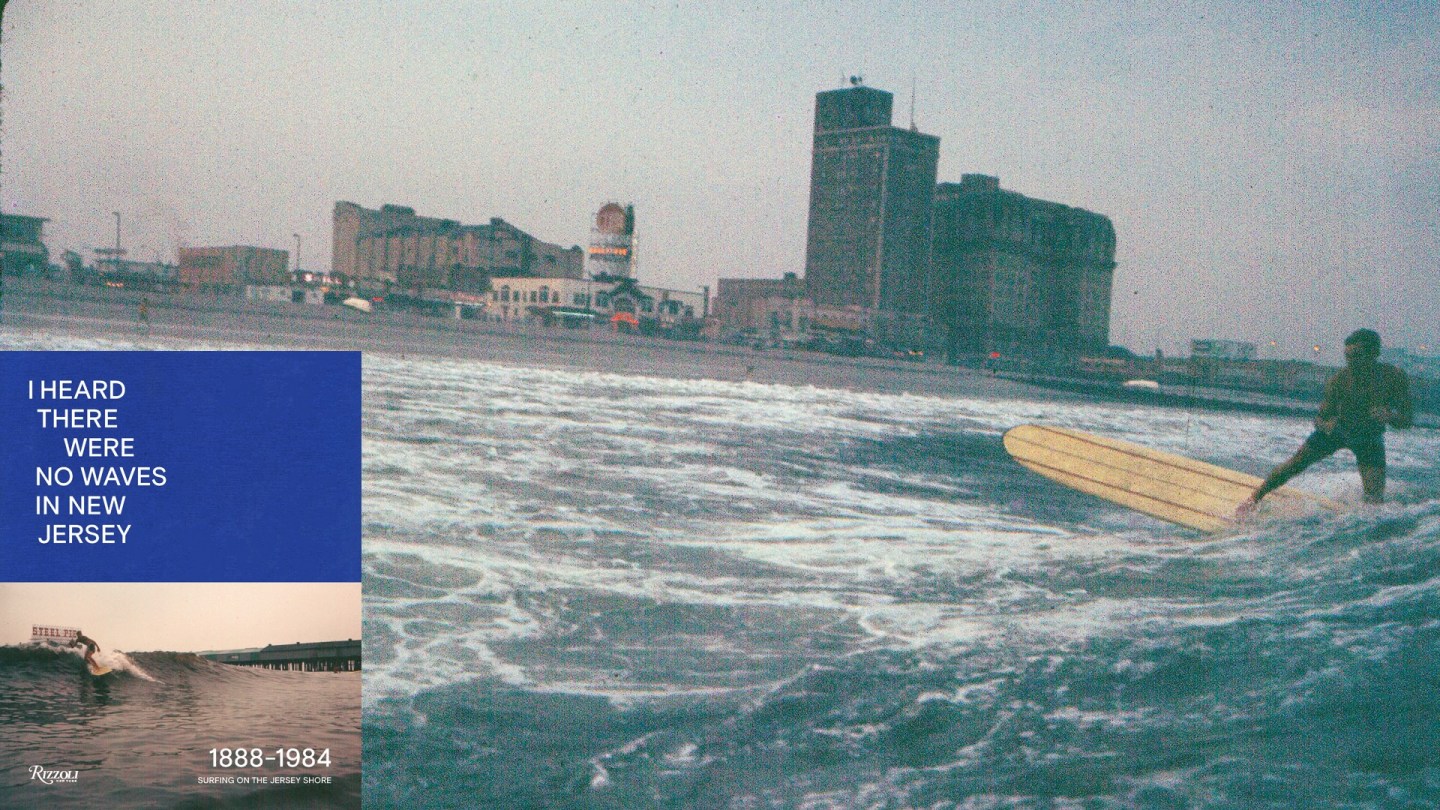

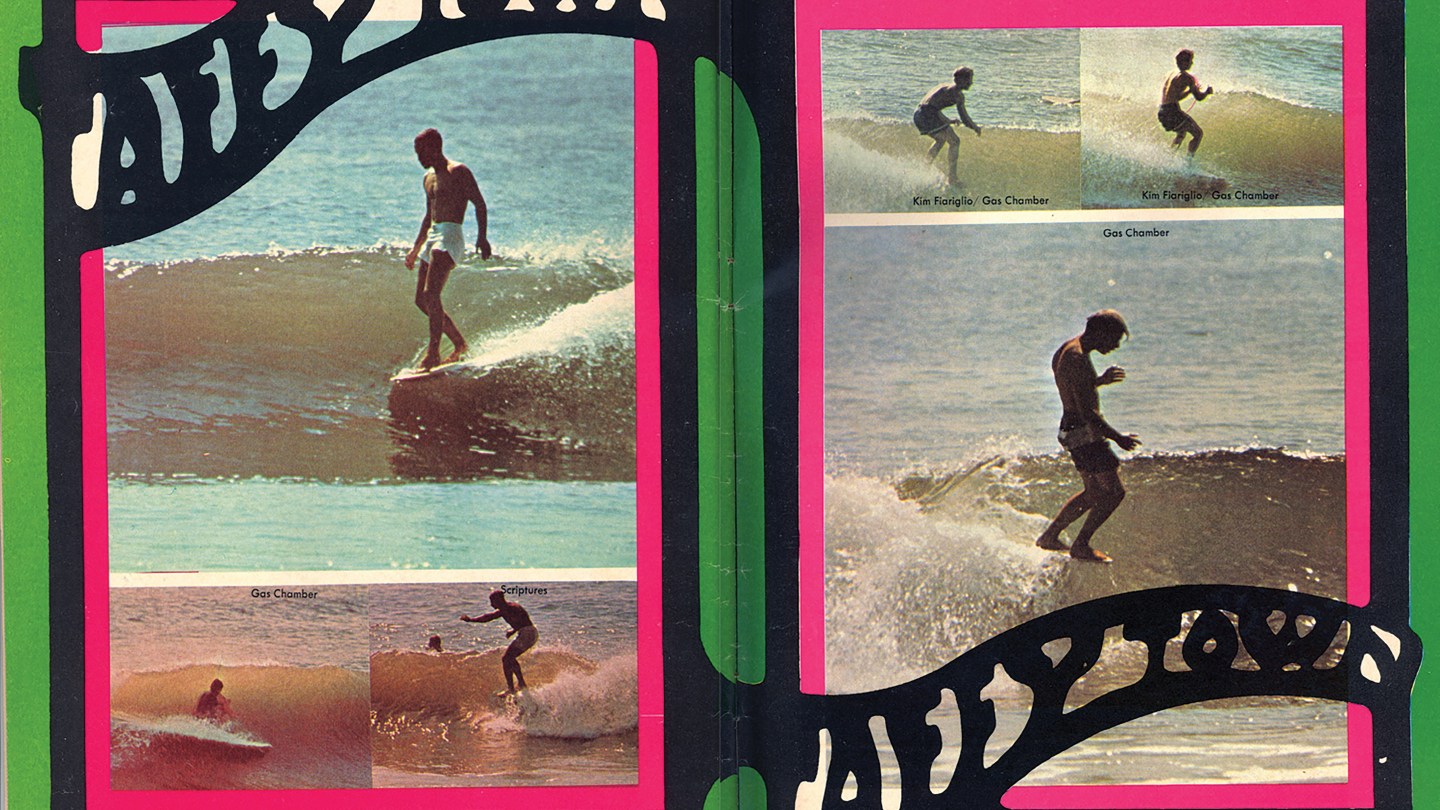

Well-timed to the release of Water Brother is another archival look at surfing and surf culture on the East Coast in I Heard There Were No Waves In New Jersey: Surfing on the Jersey Shore 1888 – 1984, a coffee table photo book authored by Danny Dimauro and Johan Kugelberg and published in March of this year by Rizzoli. The book looks at the so-called “flat as a lake” New Jersey waves and points to both the scrappiness of the surfers who first ventured to surf them and the commitment of the local surf community to explore every break from every angle in every season. In the book and in Water Brother, the perhaps less glamorous, but just as devoted, East Coast surfing scene is given its due.

The resulting book is a tribute to surf culture from Cape May to Sandy Hook, capturing what it means to be a surfer in a less popular beach locale. Down-the-shore surfers have always known that there are in fact waves in New Jersey, and the chronicle of photos and news stories from a century of surfing along Jersey’s abundant coastline is a joy to flip through. In some photos, it’s possible to catch the Atlantic City casinos twinkling in the background; in others, early bird surfers cross paths with people still out partying after a night out on the town. It’s as colorful a scene as Santa Cruz or Nazare, just with slightly more subdued waves.

A large portion of the ephemera and photos found in the book were originally sourced from a very special place in Tuckerton, New Jersey—the New Jersey Surf Museum at the Tuckerton Seaport. There, after paying only a $5 admission fee, visitors can take a stroll around Tuckerton Creek and pop into buildings dedicated to maritime life in the bay of the Jersey Shore, including the surfing museum. When I visited the Surf Museum this summer, it was like walking into someone’s long-lived-in house—boards were on loan from all over the country, old copies of LongBoard magazine were thrown about on low tables, and a poem called “Surfer Girlz” was tacked to a black foam board behind an empty counter. It’s no surprise that the Rizzoli book was dedicated to the New Jersey Surf Museum and N.J. Surfing Hall of Fame. It’s a treasure trove of keepsakes from decades of surfing the Atlantic coast.

There’s nothing like getting into surfing, especially now. From the Olympics to the N.J. Surfing Museum, there’s so much in the archive to pull inspiration, tips, and excitement from. The first time I went out myself, I avoided the main surfing spot at the Ventnor Pier in New Jersey because at that point I had no idea the rich legacy of surfing down the shore, and I felt quite literally out of my depth. I figured my flapping about hopelessly in the ocean was just the way surfing went in New Jersey, where the Surfline wave report for the first couple of months I started surfing never upgraded above “poor.”

But now, with greater access to and understanding of the legacy of surfing on the East Coast, it’s more than a point of pride to go out there and flap around on the waves, even if I haven’t upgraded myself to the Ventnor Pier lineup just yet.

When I asked Abbruzzi what he hoped to take from his film, he said he hoped people would realize that in life, in surfing, in expanding our horizons, it’s never too late.

“It's never too late to better yourself and better your community,” Abbruzzi told me. But is it ever too late to get into surfing?

“No, it isn’t,” he said. “In fact, a friend of mine who's 53 years old just started surfing a few days ago. And he's really into it. He works part-time at my shop, and everybody always thought he surfed and he didn't. People can't believe it. And he fell in love with it at 53 years old, so it's never too late.”