It had been Ed Hardy’s dream to tattoo in Japan, and while it was mostly living up to expectations, he couldn’t help but feel just a little disappointed.

The Japanese tattooers who welcomed him operated differently than those in American shops, where the majority still worked in assembly-line fashion for soldiers and sailors: Come in, point at something on the wall, go to the first guy for your outline, second guy for your shading, third guy for your color, then get the fuck out. It’d been nearly 30 years since World War II ended but the United States was constantly in conflict with someone somewhere, and the efficient, military-centric assembly line tattoo style had stuck around in American shore towns.

Not in Gifu. Appointments were made by referral only, and instead of storefronts, tattoo artists operated out of private studios. Clients removed their clothing to reveal bodysuits and intricate displays of the imagery and symbols that Hardy had obsessed over since he was a boy, sent trinkets by the father who spent most of Hardy’s childhood at sea in the Pacific.

He watched in awe as his host, Kazuo Oguri, performed hand tattoo sessions, tebori, with bamboo needles and small, quick movements of the wrist, delicate angling of the curved needles to push ink into the opened skin. A scholar as much as an artist, Hardy got his start drawing tattoos on his friends when he was 12, creating flash sheets out of the tattoos he saw on sailors, but that was only the beginning of a lifelong fascination that he could never abandon, even after fine arts and printmaking training at the San Francisco Art Institute. Watching traditional hand tattooing in person was the culmination of nearly a decade of fascination with Chinese and Japanese folk art.

Hardy was the first westerner to be invited into the secretive world of Japanese tattooing, a once-in-a-lifetime learning experience that he couldn’t afford to squander. There was just one problem: He wasn’t doing quite as many traditional Japanese tattoos as he envisioned when he dreamed of tattooing in Japan. As it turned out, tattooing being a quintessential act of rebellion, the Japanese youth and Yakuza were much like the hippies and bikers back home who didn’t want the same tattoos that their old man had. They wanted something new. And those who had heard of Hardy’s designs wanted an Ed Hardy tattoo: bold, traditional American lines and symbols like panthers, eagles, hearts, daggers, skulls.

This was 30 years before the first t-shirt with an Ed Hardy design was ever sold—Hardy never designed a shirt, but did license a few dozen of his designs to a marketer he met at a party—and its subsequent snowballing into a multibillion-dollar global fashion brand. And it was shortly after Hardy’s visit that a subculture of Japanese rockabilly aficionados exploded and biker Americana fashion came to dominate Japanese streetwear. Unlike the typical tale of cultural theft, this event has always felt more like real cultural exchange.

Hardy was flattered and determined to satisfy his Japanese customers with something new. He had spent the free love era tattooing unicorns and wizards on hippies, careful to respect his customer’s tastes but always dreading each time he was asked to reproduce the same design that had hung on his wall for an eternity. In Japan, customers didn’t want a unicorn, necessarily, but they too wanted the diametric opposite of the ex-military symbols that decorated the biceps and calves and sins of their fathers.

Kazuo Oguri listened to the snapping sound as the needles exited his thigh, careful to alternate tension in his fingers for entry and exit, tapping the small mallet on the end of the flat end of the bamboo opposite where the needles were tied. The sound, or shakki, should maintain a consistent rhythm when done properly. In the future, he would tattoo a line about a centimeter long before dipping the needles for more ink, but for now there was no ink in sight. Oguri practiced on his thigh with dry needles, scarring himself until he could get it right.

His master was asleep upstairs, tired from a day of tattooing and a night of drinking and beating both his wife and Oguri. The beatings came and went through the years, the drinking always consistent. At one point, the beatings had gotten so bad that Oguri fled to the train station, abandoning his apprenticeship, until the master’s wife fetched him. I told you that this would take courage, she told him. He thinks of you like a son. He can’t say that, but he’s proud of you. Please don’t abandon him.

For the first three years, Oguri wasn’t allowed to touch needles or ink, instead sweeping the floors, chopping wood, fetching groceries, or doing errands. It was forbidden for him to go anywhere near a customer, instead watching his master work from a respectful distance when someone was there for tebori, the Japanese tradition of hand tattooing. When the master would pass out, Oguri would fetch the tattoo needles from the toolbox and practice on his thighs.

Oguri appeared on his master’s doorstep as a teenager, homeless and starving. He’d fled what remained of his home city of Gifu. Oguri was 12 in July 1945 when the Americans destroyed over 70 percent of his city with napalm and bombs—not the bomb, but nearly 1,000 tons of incendiaries. Four weeks later, the atomic bombs burned, vaporized, and otherwise killed somewhere between 125,000 and 226,000 Japanese citizens with man’s most terrifying creation; fishermen and businessmen, entertainers and chefs, families, children. America committed the world’s first-ever instantaneous genocide. Everyone who has ever known of The Bomb has dreaded it. For those who survived it, the effects weren’t just psychological.

Japan entered an unprecedented economic and humanitarian crisis. Crime and gang activity rose significantly in the years following the war. Oguri started a street gang in Gifu and, after stabbing someone in a fight, fled to Tokyo to avoid prosecution. He quickly ran out of money and was living on the street, sleeping under tables in a public park, scrounging for food from trash cans. He stumbled across a sign on the front of a house. Apprentice Wanted, it said, with no description of the work. He knocked on the door.

The master’s wife invited him inside and sat him at the table for green tea and rice cakes. His stomach growled and, when she left the room, he ignored his manners and ate everything on the table in moments.

Oguri heard the master descend from the second floor and had a moment of shock when he saw arms and legs covered in tattoos, assuming that tattoos were only for the Yakuza. Hungry and homeless, Oguri lied when the master asked if he was an artist in school, telling him he’d always wanted to learn to tattoo despite poor marks in art classes. During his apprenticeship, Oguri could ask no questions, only listen. On afternoons his master would take him for walks so they could observe their subjects. I don’t draw cartoons, his master told him. We are watching koi fish because we are responsible for bringing the koi to life.

Designs were based on folk art and drawings by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, one of the last masters of ukiyo-e woodblock prints. The majority of Kuniyoshi’s original work was either destroyed in the war or pillaged, leaving originals in the hands of collectors in the United States, France, and England. Oguri and his master worked from reproductions, with the exception of some pieces from smaller towns that weren’t bombed that eventually were brought back to Tokyo for preservation.

Oguri and his master, then, were more than artists. They were chroniclers, keepers of knowledge in danger of becoming lost for future generations. On the backs and thighs and legs of their customers were the people’s histories of Japan and its culture, not the new history being rewritten by the new Japanese government and the occupying American forces.

Oguri left after six years—the apprenticeship took five years, and Japanese customs of the time dictated that he spend his sixth year working for free in his master’s shop—and became that chronicler for Gifu. Upon returning to his hometown, he later wrote, he found that the man he had stabbed did not die, after all, and there was no warrant for his arrest. He could return to his home city without fear of pursuit. He opened his tattoo studio soon after, and Kazuo Oguri became known to the world as Horihide.

When Oguri hears the snapping now, this time it’s his client’s skin instead of his. He’s carving koi fish and octopus, samurai and kabuki, just like his master taught him. On the backs of his clients are the stories of Gifu, of Kuniyoshi, of his master and his wife, Ane-san, who he loved so dearly. Then, in the late ‘60s, he saw the future on the arm of an American sailor. A man was walking by with a tattoo like none he had ever seen, packed with colors that you weren’t supposed to be able to put into tattoos; influences that were familiar and Kuniyoshi-esque combined with something more obscene and aggressive. Oguri asked the man where he’d gotten the tattoo.

It was a Sailor Jerry, the man told him.

Oguri found a translator and began written correspondence with Norman Collins, known in the tattooing world and to the world at large as Sailor Jerry, at his infamous Smith Street shop in Honolulu. Jerry was a virulently anti-Japanese racist (“Have been corresponding with a Nip tattoo artist from Gifu,” he wrote in one of his tamer letters on May 3, 1971), but he cared about tattooing. So, he sent Oguri the information for Spaulding & Rogers, a tattoo supply company in Albany, New York.

After a few years of exchanging designs, pictures of finished tattoos, flash art, and ideas, Oguri arranged to meet Sailor Jerry at his place in Honolulu for the world’s first ever international tattoo convention, seven tattooers from three countries. When Oguri arrived at the airport, Sailor Jerry was there to greet him in a baby blue Thunderbird, the same color as his motorcycle, with two much younger men: a handlebar-mustached beatnik and a heavy-set guy with curly hair.

The stocky one stepped forward, bowed, and introduced himself with Japanese that was crude in pronunciation but accurate in customs. His name was Ed Hardy.

Right around the time that Oguri was en route to Hawaii, a gangly heroin addict was stumbling past the burned-out buildings and abandoned cars of the Lower East Side of New York City, because he’d heard that it was a great place to get a tattoo. He didn’t know what street he was supposed to go down so he kept looking for cosmic signs that he was headed in the right direction: a flock of geese flying south, a trash can overturned with its garbage pointing down an alleyway. Eventually he heard an animated conversation about East 4th Street and that was where he found Thom deVita sitting on a stoop, waiting for a customer to walk by.

DeVita led him into his apartment, past a darkened room with shadows and trinkets that seemed to vibrate and pulse, a living organism that threatened to swallow visitors whole. When he arrived in the bright natural and overhead light of the tattoo studio, he wondered if he’d shot the best batch of drugs he’d ever scored. DeVita was shirtless, with swirling patterns going up and down his spine and rib cage and arms, layered in with Chinese dragons and cryptid beasts and symbols. And beneath the man himself, the tattoos seemed to flow from the floors, where deVita had crafted similar patterns in the wood with carvings and paintings. The entire room was a work of art, with all variables considered: interplay between the lighting, the artist, the surroundings, the tools, and of course the subject, who was now handing a carefully sketched drawing over to deVita as a guide for what he wanted—a meticulous tapestry of flowers to complement the rose tattoo that he already had in the middle of his forearm. Come back in a week, deVita told him. I’ll have it ready. Hey, what’s your name by the way?

Nick Bubash, he said.

Bubash came to New York City to become an artist, initially taking a job at a commercial studio. It was only half of a rebellion; his mother was an artist, so it wasn’t much of a deviation from his parentage. His father is part of medical history, as the first person hired by Jonas Salk to work with him on the development of the polio vaccine. But America has no capacity for nuance and a penchant for idolatry, so Salk became the household name while the other researchers spent the rest of their lives getting second looks when they claimed to be part of one of the century’s biggest discoveries.

Bubash had spent his childhood drawing, always sketching what he saw while sitting on the floor of his home at the foot of his mother’s chair. He’s probably as skilled as anyone at drawing a middle aged woman’s knee. By the time he was a teenager, it was clear that this was a unique talent, and there didn’t seem to be much of a ceiling to it. His drawing skills improved year over year, his imagination became more active with age, his eye and his taste refining with time.

It was Sailor Eddie of Camden, New Jersey, who told him to see Thom deVita. Eddie had a mouth full of gold and leaned into the pirate voice gimmick a bit much, but was a skilled technical tattooer for the time, himself having done deVita’s dragon-patterned leg with fellow east coast artist Paul Rogers. In the ‘60s, there were barely a few hundred tattooers in North America, so each coast or region had its own little spiderweb of influential artists. Word got around fast if someone new came on the scene.

A week went by and Bubash returned to deVita’s studio, anxious to see the stencil they had created for his drawing. His heart dropped when they produced the stencil. Bubash had given them a painstaking reproduction of a Michaelangelo from an art history book, and deVita was now showing him a stencil of flowers that looked like they were drawn by a fourth grader. He politely seethed about permanently inking his arm with something he could’ve drawn better himself, before sitting down to get tattooed, so as not to offend his host.

As soon as the process started, his regrets melted away. deVita was quiet, with a quick sense of humor, and an odd way of putting people at ease. There were times he reminded Bubash of his uncle, a professor who read from morning to night and always spoke about a continuum of knowledge, shared secrets and symbols between people and cultures. By the end, he loved the tattoo, crude design and all. He went back a couple of weeks later, this time with some drawings he’d done of English-style dragons from old fantasy stories and oil paintings. You can come back anytime, deVita told him.

Thom deVita built himself a mystique: When people asked when he started tattooing, he’d tell them it was the day after New York City banned it in 1961, an answer too perfect to be true but impossible to rebut. He was known for giving $30 tattoos to working-class men and women in the neighborhood, occasionally dabbling in Chinese and Japanese stylistic flourishes while predominantly sticking with his tribal patterns and traditional western symbols. The “$30 tattoo” was something of a misnomer: It cost you $30 for the panther, but if you wanted some clouds over it, that was another $30, a pattern around it another $30, and so on. When Bubash began doing elaborate back pieces that worked in American traditional style and symbols with Hindu mythology and Indian linework, those cost $20 per element, because he wasn’t allowed to charge more than deVita in his own shop.

DeVita never let anyone other than Bubash tattoo out of his shop. Bubash figured he took him in because he saw his talent and his addiction, opting to nurture him instead of letting an artist waste away. It’s also possible that the 5-foot-5 deVita didn’t mind having a 6-foot-3 guy in the crew, tattooing being a rough trade. But the neighborhood respected deVita, because he respected them.

There was a small war of words when deVita began running advertisements for his shop that said “Tattoos Needn’t Be Expensive,” a potshot at a specific tattooer on the West Coast who had begun ticking up his prices as demand exploded for his new, unique blend of American traditional and Japanese traditional.

They were friends, deVita and this high-priced tattooer named Ed Hardy, and Hardy always took the jokes in good stride. They met in 1971 when Ed visited New York, a necessity given that deVita rarely ventured farther than five blocks from the East River. Hardy later would describe the shop as a power vision, something that permanently altered the way he saw tattooing as an art form.

DeVita captured Hardy’s imagination with his mystique. DeVita and his apprentice Nick Bubash weren’t tattooers, he realized, but artists who did tattoos. And they built an entirely new reality in the Lower East Side. In deVita’s shop, you were surrounded by art and trinkets made by the man himself, surrounded by tough guys who cracked jokes or quietly watched on as the artist worked. (Among them was Blackfoot Bobby, a petty thief whose entire foot had been tattooed with black ink, who was not to be confused with Black Dog Bobby, whose dog was black.)

It’s not especially controversial to say that deVita’s tattoos could lack technical rigor, but you walked away with something unique and unforgettable: a part in the ritual.

Nick Bubash has his studio in the Crafton area of Pittsburgh, an old hair salon that he bought last year and hollowed out to create a workspace. The walls are gone but you can still see the layout, as the customer area has pristine linoleum tiling while what used to be the office area has yellowed and feels like it may crumble beneath my shoes. Bubash walks me through decades of work, beautiful sketches and paintings, sculptures of rearranged animals and junk-shop religious symbolism. In the corner, a sculpture of a tree demon, branches protruding from its head and limbs, his face petrified in the shape of a tortured roar. It’s raining. For two weeks, every rainstorm in Pittsburgh has felt apocalyptic.

He lights up when I tell him I'm writing about Oguri, fondly recalling the letters they exchanged in the mid-'70s, when Bubash was a member of an American tattooing club that the Japanese master started. He would write you right back, he was very responsive, he tells me. We would share designs and ideas, you know. He was always very kind.

Bubash has been clean for decades. DeVita called heroin his penitentiary and told Nick he would walk out when he was ready; it helped that he encouraged Bubash to enroll in art school, which he finally did at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in the early 1980s. He graduated and found success as an artist, producing work that’s been displayed in museums around the world and purchased by art scene celebrities like Lou Reed.

He describes the time his freshman year when he wandered into Philadelphia Eddie’s tattoo shop and saw pictures of his backpieces hanging on the shop wall. He told the girl working that they were his pieces. Don’t move, she said. Eddie wants to talk to you. Bubash waited until she went into the back and rushed out the door, determined not to get talked into tattooing again.

Still, he says to me. I can’t get away from this tattooing stuff, you know. It just follows me around.

He shows me his artwork, the pieces that have been displayed in the Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh; in 2013, he created a new mascot for the dollar bill called the Vark, a vulture/shark cryptid carrying a hellfire missile and a wilted olive branch. We’ll Getcha, it says, instead of E Pluribus Unum. We make plans for him to put it on my back, but the discussion of his art reminds him of a story. Vice commissioned a documentary about deVita, and it features Bubash prominently, walking through his home, talking about his life.

From another room, deVita started shouting at Bubash. Where are you in tattooing, he was saying to Bubash. Where are you, what’s your legacy? Bubash lost his temper and pulled his phone out of his pocket to pull up a picture of his sculpture on display, and he repeats that for me now, pushing it forward towards me like he did to deVita. His phone has a picture of his daughters on the home screen, both grown now.

Did any of those little fucking cartoon artists ever end up in a fucking international art museum, he tells me he shouted at deVita. You were the one shoving art school up my ass for seven years. DeVita smiled, happy that he was able to successfully push his pupil’s buttons.

DeVita died in 2018. Thom said me and Hardy brought fine art to tattooing, Bubash tells me, his leg crossed while a filterless Camel burns in the ashtray at his right.

Legends are alluring because of their tidiness. The world is complicated, and mythology allows people to simplify complicated subjects like morality or creation. Ed Hardy understood that better than any tattooer, and possibly any other cultural tastemaker of the latter half of the 20th century. He’s built his own mythology thusly, and much of it is deserved. So, here’s how the legend goes.

The convention in Hawaii between Sailor Jerry, Kazuo Oguri, Ed Hardy, and Mike Malone, a famed artist and later Hardy's business partner, was perhaps the most important inflection point in the development of modern western tattooing. Given that it’s a legend, it’s possible to sum it up in a sentence: Hardy’s connection with Oguri led to an invitation to tattoo in Japan among the back rooms and parlors that no westerner had ever set foot in, and when Hardy returned to America, he brought with him the Japanese tattooing customs and rituals that would come to define what we think of as tattooing in the 21st century.

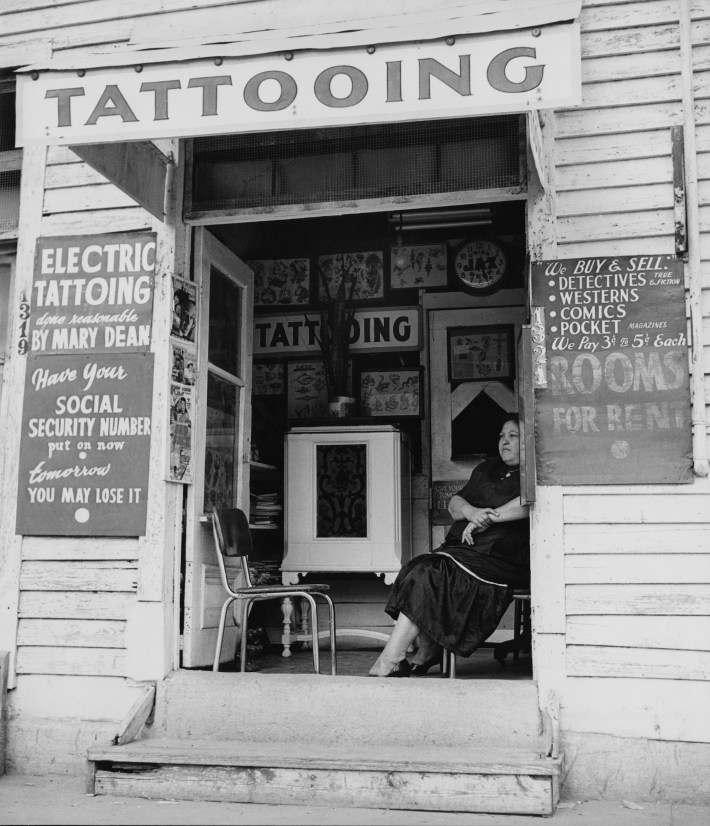

Before Hardy came back from Japan, even the top-tier shops like those run by Thom deVita, Huck Spaulding, or Paul Rogers and Sailor Eddie were predominantly flash tattoo shops. You walk in, you point at the wall, you get what they drew for that week, or the month before, or whatever is hanging around the shop. Customers were getting customized pieces, but they were the exception rather than the rule. When Hardy returned from tattooing with Oguri in Japan, he opened the country’s first-ever appointment-only/referral-only tattoo parlor. There was no shopfront and nothing to point at on the wall. If you knew the right person, you could get an appointment with Ed, and then he went about creating the tattoo with you. What do you want? Where do you want it on you? Do you like dragons or serpents? Daggers or swords? Eagles, tigers, a gorilla, a samurai, a collision of sailor art and Japanese folk art, or Chinese dragons and biker iconography—if you wanted it, Ed could put it on you. Tattooers used to make new business cards on a near-weekly basis, so it’s hard to lock down one specific marketing hook for a given tattooer, but one that stuck for Hardy was always “Wear Your Dreams.”

Hardy’s decision sent shockwaves throughout tattooing, and the big-name artists (pettiness and competitiveness is extremely common in tattooing, but particularly with the old-school American artists) felt forced to step their game up and increase the amount of customized work they did for clients. Fast forward a couple decades and the natural progression of customer empowerment leads America to its current state of tattooing, where multiple shops can be found in most neighborhoods and appointment books are predominantly filled with custom pieces for clients. Flash is now mostly reserved for the increasingly rarer walk-ins.

Hardy is undoubtedly one of, if not the single-most influential tattoo artist of the 20th century—western or otherwise. He was always open about his intent: He wanted tattooing to assume a more ubiquitous place in culture and leave behind its subterranean beginnings. And the legend is built in large part because he not only delivered on that mission, but he dedicated his life to tattooing such that almost any notable event of the 20th century in that world has only a few degrees of separation from Hardy. Horiyoshi III, perhaps the greatest Japanese tattooer in history, started using electric needles for outlines instead of using tebori in the 1990s. Why? Because Hardy showed him how to use a coil machine when they became friends in the ‘80s. BDSM and kink scenes, particularly large groups of gay men, began spending big on tattooing in New York City in the 1960s and early 1970s. Why? Because Hardy tattooed at orgies, alongside deVita and Mike Malone.

Hardy made a concerted effort to study new artists and styles, like he did in 1971 when he went to New York to see deVita, or even earlier when he visited Long Beach Pike shops as a teenager. He started a pen-pal relationship with Sailor Jerry to exchange designs, ideas, and tips. Hardy was far from the first talented artist to pick up a machine. Rather, he is perhaps best understood as a champion and curator, like a talent scout who regularly called artists up to the big leagues. Tattoo City opened in 1977 in San Francisco and had a regular rotation of artists like Daniel Higgs, Eddy Deutsche, and Freddy Corbin—household names in the tattooing community. Hardy built an empire on his taste as much as his talent.

To that end, much of Hardy’s legacy is in what he brought to the presentation of tattooing. Working with V. Vale of RE/Search magazine fame and general San Francisco punk rock infamy, Hardy launched Tattootime, beautifully photographed books of artists and bodysuits and elaborate backpieces accompanied by literate and thoughtful essays about the influences, the work, the evolution. Prior to this, the majority of tattoo art was only available in distribution catalogues, or lurid magazines. Tattootime elevated tattooing simply by treating it like art, and in the process established Hardy Marks Publications as the authority on tattoo history and mythmaking.

And while Hardy used that platform to elevate some extraordinary artists and the practice of tattooing itself, he also used it to cement his own legacy. It became a self-perpetuating loop: Alongside Mike Malone, Hardy owned and archived just about every relevant piece of tattooing history from 1970 onward, and he released and published them at his whims. The definitive book on Sailor Jerry, for example, was published by Hardy Marks Publications and features curated letters that Hardy received from Jerry prior to the convention in Hawaii in 1972, showing a man thoroughly and obscenely schooling a young talent whose gifts he clearly respected. Hardy’s legacy is thus intertwined with that of Sailor Jerry, the torch-passing officially enshrined as canon.

The legend only has room for a small handful of names: Kazuo Oguri, Sailor Jerry, Ed Hardy, Mike Malone. Despite the fact that she’s consistently excluded from the retelling by Hardy and most of the tattooing world, Kate Hellenbrand, known in tattooing circles as Shanghai Kate, has a credible claim to being part of that history.

At her home in Austin, Texas, the 77-year-old Hellenbrand is sitting on a treasure trove of artifacts from the era, including never-published photographs of Oguri, Malone, Hardy, and Sailor Jerry in Hawaii together. She has letters, too, and corresponded regularly with Hardy and Jerry. The letters from Sailor Jerry to Shanghai Kate show a strong and heartfelt fondness for the young tattooer. To hear her tell it, the legend of the convention is mostly true, but there are a few key details left out. Hellenbrand claims that Hardy wasn’t actually invited to Japan out of mutual respect, as is often repeated, but instead strong-armed his way over while Oguri was tattooing his back with a tebori tool, offering him business propositions until Oguri finally gave in and gave him permission to come to Japan.

The convention that Hellenbrand describes is much messier than the loving cultural exchange portrayed by the Hardy Marks mythology. Malone and Hardy were feuding over getting attention from Jerry, as it became clear that Hardy’s work was so much further advanced and Jerry was much less interested in Malone’s work. Sailor Jerry, rather than opening his arms to a Japanese tattooer willing to break tradition and exchange ideas with westerners, used the meeting as an opportunity to humiliate and belittle the shy Oguri. When Jerry took Hardy and Malone (and Hellenbrand, usually left out of this particular part of the tale) to the airport to pick up Oguri, they all brought gifts as customary in Japanese culture, and Oguri held corresponding gifts for each of his welcoming party. But Jerry didn’t bring a gift, didn’t bow, and didn’t say a word until after he’d made an unannounced detour to the USS Arizona Memorial. Kazuo, he said, this is Pearl Harbor. This is what you did to us. The other tattooers didn’t speak on the car ride back to Jerry’s house.

And then there was the peony. A photo of an unfinished peony tattoo on Jerry’s shin has floated around for years, but never had a firm backstory for it. According to Hellenbrand, that’s because the backstory is deeply cruel: Jerry gave Oguri an electric coil machine for the first time and told him that’s what he wanted him to use—the equivalent of giving an expert hang glider the controls of a 747 with no intermediate lessons. Oguri eventually got the hang of it, but Jerry made a big show of how much it hurt and what a poor job he was doing. Eventually, during the shading, Jerry tapped out. Hellenbrand is convinced it was an intentional way of making the Japanese tattooer “lose face,” an important concept in his culture. A public humiliation must be taken with grace, but it’s a burden and shame that Oguri carried for the rest of his time in America.

These are small details, but they’re also the kinds of details that legends and mythology gloss over in order to sustain themselves. Nobody wants to hear about a racist like Sailor Jerry humiliating a young Japanese artist as revenge for Pearl Harbor, or hear that Oguri and Hardy’s relationship was primarily financial in nature. Those details start to make this event, and everything that came after it, just another example of the west’s need to prove its cultural supremacy—something not unfamiliar in postwar Japan.

However, there is one larger detail that Hellenbrand is especially hung up on, and that’s Sailor Jerry’s legacy. Like Ed Hardy, Sailor Jerry is no longer just a person but a brand, or a concept. His likeness and his art have been repurposed as a way to sell products to people, but instead of t-shirts it’s spiced rum. Sailor Jerry Spiced Rum sells over a million cases per year and is based on his original recipe—a recipe that Hellenbrand says never existed. Worst of all, she says, Jerry and his family, most notably his widow Louise Collins, had no say in the decision to make him a household name selling products to the types of hip liberal weirdos he would’ve wanted dead in the ‘60s. That decision was made by Hardy and Malone in the 1990s, and they both profited handsomely from it.

Jerry died suddenly of heart failure in 1973 while Hardy was still in Japan, and his shop and everything in it was purchased from Louise Collins by Malone—under dispute by Hellenbrand—for $20,000. Untold amounts of Jerry’s artwork and flash and tools were in that shop, which is essentially what Hardy and Malone would later license in partnership with a Philadelphia marketing firm. Jerry’s art started showing up on clothing, then eventually on a namesake rum, and then suddenly it wasn’t just the art, but Jerry himself on the bottle, the website, the marketing materials. Sailor Jerry had been resurrected as a hip rebel for a multimillion-dollar brand while his widow sat in Honolulu with nothing but the $20,000 she received in the ‘70s. Hellenbrand made a big deal about it in the tattooing community shortly after Malone died in 2007, and Louise Collins started legal proceedings a few years after that. A civil suit was settled in the fall of 2020 for an undisclosed amount.

When Hellenbrand first went public with this information in 2009 she was attacked as a con artist or as delusional by other tattooers, many of whom had direct ties to Hardy or just a degree or two of separation via apprenticeship or friendly circles. Hardy’s son Doug, who now tattoos at his father’s shop Tattoo City, implied that Hellenbrand was nothing more than Malone’s girlfriend at the time, accusing her of stealing Sailor Jerry flash art and Malone’s photographs and lying about her relationship with Sailor Jerry. With the letters provided by Hellenbrand, those accusations start to lose credibility.

The letters very clearly show a mutual respect. Jerry is open with her on how to start her own shop, providing tips and secrets that he’s learned from the business. Jerry even implies that he’d like her to come tattoo with him and, perhaps most relevant given the way his legacy has been repurposed to boost Hardy’s credibility, he expresses dismay at what has become of his star pupil who had just abandoned him for Japan in 1973.

“Yours here and do understand your resentment against Ed, and I do think you have pegged him right all the way. I write to Ed the artist now, no longer Ed the person,” Jerry wrote in one letter in spring of 1973.

In another, Jerry is more direct about wanting Kate to tattoo with him:

“I cancelled my commitment to Ed so that leaves the way open and if such a thing comes about, I could use you both over here but we’ll talk about that when the time comes and a lease is in the bag. Don’t know whether Mike would want to take a chance on losing his old lady again by coming over here to hang with JSan but it’s a chance we’ll have to venture!”

While it’s clear that Shanghai Kate Hellenbrand is much more intertwined with tattoo history than its mythmakers would have you believe, it’s also impossible to validate the unknown. The letters help to provide context and credibility to her version of events, but nobody can claim to know Jerry’s intent or his true feelings toward Hardy, or whether they would have reconciled had Jerry lived long enough for Hardy to return from Japan. In any case it paints a much more complex picture of the Ed Hardy legend; something a little more flawed, more human. The sort of things mythology tends to gloss over, because those details often reveal the true cost of empire-building.

In traditional Japanese tattooing, there’s a custom where the artist will save the eyes for last. Adding the eyes to a creature or a samurai or a geisha is said to add life to the tattoo, elevating it from just another design to a living thing of its own, with its own soul and story to tell. After weeks—potentially years, depending on the size of the piece—the customer makes his ceremonial final appointment, and the eyes are added to finish the piece. You know why they really did that, Jason Lambert says to me. Those bodysuits cost a shitload of money and nobody wants to walk around tattooed with a dragon without eyes. If you save the eyes for last, they keep showing up to pay you.

I met Lambert at Black Cat Tattoo in Pittsburgh. A former punk rocker from Texas, he started tattooing in the ‘90s mainly because his brother was doing it. He’s drawing on my left thigh with a green Sharpie in one hand and maroon in the other. The different colors help him determine where to add depth, clarify where lines overlap or should pass behind. It’s a freehand outline session, so it shouldn’t take much more than 90 minutes or so, even though the giant oni head and octopus he’s drawing is apparently turning out bigger than he anticipated. In traditional Japanese tattooing, the oni and octopus are often portrayed as silly creatures, but there’s no real 1-to-1 symbolism. Different artists from different regions used folklore and symbols as was appropriate for their own storytelling, back when information had difficulty spreading farther than a few hundred miles in any given direction.

You know Oguri follows you on Instagram, I say to him as he starts to glove up and get his needles unpackaged and in the machines. He doesn’t believe me at first, and then says he’s not really sure when or why it would’ve happened, as they’ve never met. There’s a pause and he laughs it off, saying that maybe Oguri likes it because they both draw ugly stuff.

Lambert tattoos exclusively traditional Japanese now, a decision he made about a decade ago as his interest in other forms was slipping. It’s a personal choice, but also one dictated by the modern tattooing market: There are more tattooers now than ever, and jack-of-all-trades tattooers have all but died off. That’s not a bad thing, necessarily, and it’s led to better working conditions and higher-quality art. Tattooers that are Lambert’s age, usually those that sat on both sides of the pre-aughts explosion, are quick to note that the industry is much better now, for artists and customers.

Ed Hardy won the war, thus his ability to write history. Tattooing is a consumer product. As Lambert unwraps his needles, he jokes that he can’t remember the last time he soldered his own. Tattooers once had to create their own needle formations for line thicknesses, but now they come prepackaged and sterilized from China. Like most other products, it’s objectively better by standard measures—safer, better looking, aesthetically more appealing—but increasingly loses its humanity. The sons and daughters of the traditionalists have effectively milked every last cent out of the counterculture they created.

Even then, it’s something of a misnomer to give Hardy the credit, or to give it to Kate Hellenbrand, or Sailor Jerry. Even Kazuo Oguri shouldn’t get all of the credit, though he’s likely more deserving of it than any of them. If Thom deVita is correct that tattooing is the ultimate expression of folk art, then tattooing doesn’t now nor did it ever need any of them. They are tools of the art, not its creators. And if folk art is collective memory—lessons and symbols and fables—then what could be more fitting for a 21st-century western culture than something that evolved from being a carnie hustle to a wartime badge to another noisy product in history’s largest shopping mall?

I couldn’t get Hardy for this story, something I lamented in the shop. He’s stopped doing interviews recently, perhaps deciding that he’s given enough after countless books and lectures and documentaries. I also wasn’t able to get in touch with Oguri, now in his late 80s, though that’s no surprise: Japanese traditional tattooers are hesitant to talk to anyone about the craft unless they’re in the club, though Hellenbrand still maintains a friendly relationship with him. I couldn’t confirm whether he still tattoos in Gifu, but he does sell original paintings and flash on Instagram for between $200 and $500.

Lambert fires up the coil machine and it whirs, like hearing construction on the street from an apartment window but somehow up close—jackhammer speed with a tablesaw type buzz. You ready, he asks, and puts an initial test line in so I can adjust. Then it’s smooth sailing, alternating tension in the skin, not quite a pinch or a prick but like holding your hand above the stove for a second too long. I’ll never look the same again, and that’s the idea.

Hardy once told V. Vale in Modern Primitives that people freak about the permanence of tattoos because it reminds them of death. Thinking about what something will look like in 50 years forces someone to grapple with the fact that one day they’ll be 50 years older. He would later tell Vale in a book of interviews that he felt as though the surge of tattooing after the ‘90s was about empowerment and that it was inevitable, masses of people retaking control of their body. He had previously tied that concept back to prisoners and why tattooing was so big with convicts: They can lock us up in here, but they can’t have our sense of self-expression. It feels notable, then, that the rise of tattooing has coincided with the increasing sense of despair and creeping dread that pervades modern life, and for good reason. 1945 and the atomic bomb is as good an inflection point as any, but even that is too neat and tidy to be true. It wasn’t 9/11, either. Inflection points are comforting because they imply that if people could just unwind whatever complications came after, life could resume some idyll that never existed.

As the outline session winds down, Lambert switches to a rotary machine, which runs quieter and is capable of slowing the needle down enough to create textures, which he adds to the head of the octopus. I mention Oguri again and he smiles a bit more this time once I clarify that Oguri only follows about 1,000 accounts. I’m flattered, he says. This is about as animated as I get, but yeah. He’s the master.

Anthropologists haven’t yet found a single culture without body marking, often an expression of adulthood—at times unwilling. Tribal rituals where adolescent males of the species are taken from their mothers and beaten into submission for the greater good of the community. They return permanently marked, and some keep marking themselves, an expression of self against hopeless circumstances.

I pop off the table to examine my thigh in the mirror. The oni is grumpy, annoyed that this idiot fucking octopus is back again. In another month we’ll do the shading, then color. Then something else somewhere else by someone else, and it’ll be there on my skin forever unless the bombs drop and flay me alive. But if we can avoid that long enough for the ice caps to melt first, whenever whatever future lifeform unearths me, they’ll tell each other stories about my culture from the pictures on my body. If it sounds good enough, anyone will believe it.