Of the many surprises in store for me when I booted up Elden Ring two years ago and took my first whirl through the FromSoftware pain rodeo, perhaps the greatest was that I was not alone. As I have been playing Shadow Of The Erdtree, an expansion that is really more like a sequel, I have become increasingly obsessed with and moved by the game's obliquely interactive poetics.

The two words an Elden Ring player reads the most are "YOU DIED," blotting out the screen in unforgiving red script every time YOU happen to DIE. Death is an ever-present condition of the game. It is the point at which the story begins, the joist upholding the game's mythic lore, a joke told hundreds of times, over and over again, forever, until the player advances past each of the game's dozens of punishing boss fights, gaining in the process merely a new perch from which to die. "I just want as many players as possible to experience the joy that comes from overcoming hardship," the game's director Hidetaka Miyazaki told the New Yorker in 2022.

Dying is one of the game's operative verbs, and "YOU DIED" is among the few times the game ever bothers to directly acknowledge the player. Mostly the experience is one of opacity and horror, with the text of the game devoid of hints, the story told in the negative through scraps and fragments, and the player left on their own to be exsanguinated by hawks with swords for legs, rent apart by shrieking arachnoid monstrosities constructed from jumbles of grafted-on human limbs, or pummeled by a spherical assassin wearing the stitched-together skin of dead gods. This is what distinguishes Elden Ring. The process of scrying the runic lore and iterating one's way through unforgiving boss fights empowers the player, with the swelling death count the necessary ballast to keep the experience aloft.

But you are not suffering alone: If you play while connected to the internet, you are faintly tethered to the millions of other players fighting and dying in the Lands Between, whose spectral forms are occasionally visible, outlined in white, with red blood splotches on the ground to indicate where they've died. You can interact with the splotches and see their death throes, as is the case in each game of FromSoftware's Dark Souls series. Players can summon each other for help through boss fights, though even then, nobody can communicate, and the summoned player disappears into a fine mist when the fight ends.

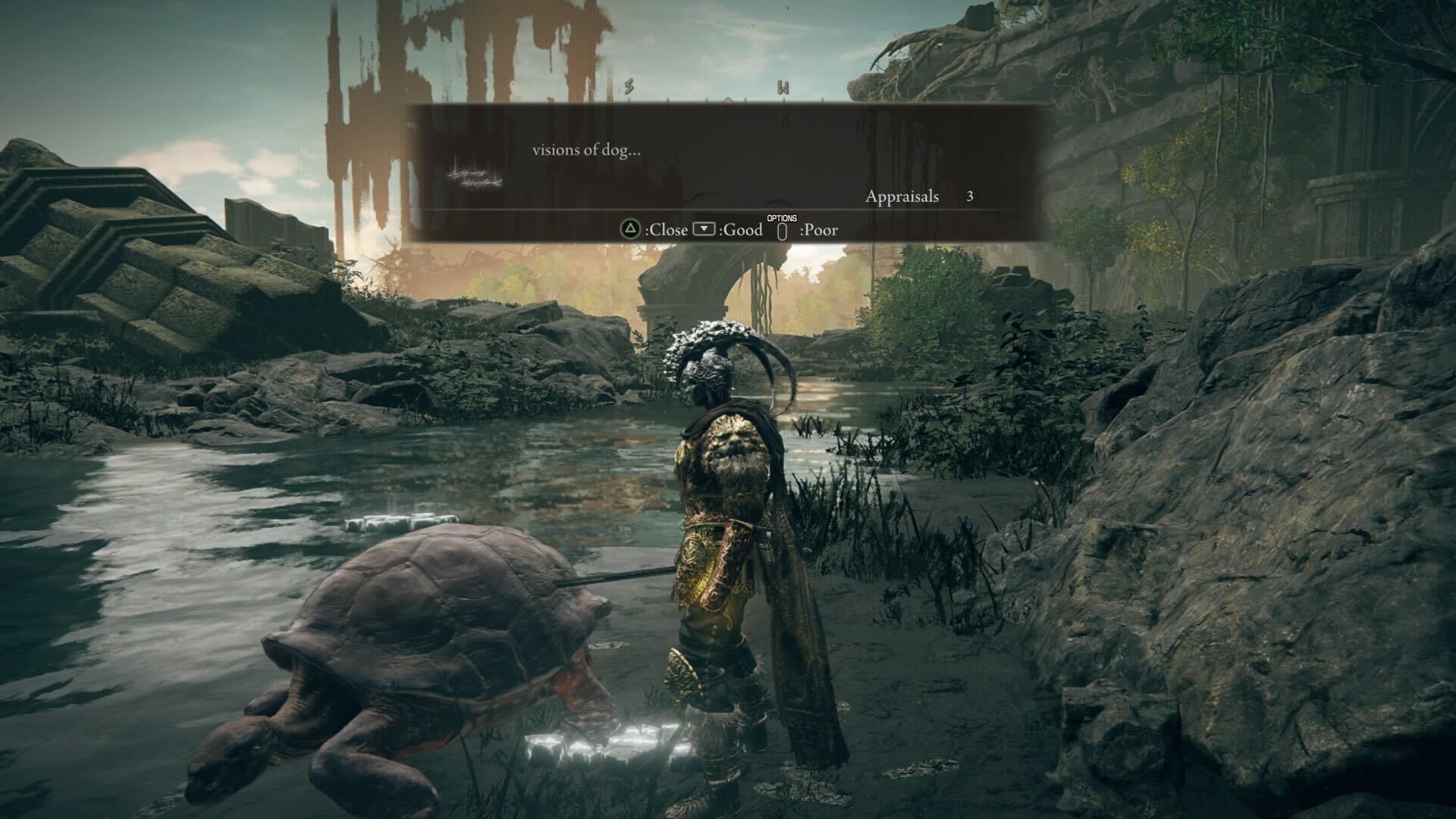

While the game itself only ever smirks at you, players can leave each other messages, scrawled out in the ground on glowing white bricks. The messages can be straightforwardly informative ("enemy ahead"), lamentory ("still no Elden Ring..."), jubilant ("I did it!"), funny ("dog ahead," adjacent to a turtle), or poignant ("if only I had a lover...why is it always sadness?"). "Try jumping" is something like a mantra, often scrawled on various cliff edges, and it falls to the player to decide if the writer is trying to prank them into another death, or revealing that a leap of faith is required in order to reach a new secret area.

The messages can include a stranger's ghost making a gesture, though most don't. Players can mark messages they find as helpful, which gives the player who wrote the message a potentially life-saving health boost. What makes the message system so special is that players' ability to express themselves is limited. Players have 372 words to fit into 20 templates. They can link two templates together with one of 10 conjunctions. This gives the player over 500 million possible messages, a sprawling but finite number containing a vast number of gibberish combinations, beyond the frontier of language, and a small number of sensible, helpful ones.

To the degree these can communicate crystalline, pure truths, it is mostly via blunt answers to yes/no questions (e.g.: Is there a skeleton ahead?). It is precisely this combination of finitude and imprecision that piqued my fascination, for even in its most precise use, Elden Ring's message system can't be wrangled by the player to communicate granular, full truths outside of the vocabulary on offer. To the player, there is a degree of interpretation. It's not prose, but something approaching poetry.

These bounds on language mirror and enhance the way Elden Ring tells its story and sets out its challenges for the player. There is no Hyrulean directness, no gimmick weapon obtained in a dungeon that you must then use to defeat that same dungeon's boss. You can beat the final bosses of the main game and DLC without ever having to know, really, what Elden Ring's overarching narrative is; maybe that guy in the Volcano Manor fed himself to a god-devouring serpent simply because he's a weird guy. There are so many obscurant layers between the player and anything like a conventional video-game narrative, and the deepest pleasure I found in the game was peeling those layers back to see what the story was for myself. Understanding Elden Ring is an act, most of all, of reading.

NPCs communicate in enigmatic, foreboding monologues riddled with archaic, confusing turns of phrase (e.g.: Mother, wouldst thou truly Lordship sanction, in one so bereft of light?), and there's real care in the work of translation here, one whose choices paint the game with a distinct linguistic hue. To truly understand the full scope of the narrative arc of Elden Ring, you have to read item descriptions and watch YouTube videos. Areas of the map, especially in the DLC, are locked behind seemingly mundane false walls. Extremely important story bits are told environmentally, and they're often tucked away in peripheral areas without any signposts. More than fine motor skills or knowledge of Japanese and Nordic mythology, the game requires attention, forcing interactivity—the very essence of video games—in places it's typically not found.

The same logic holds with regards to Elden Ring's gameplay. You have to DIE over and over again until you know enough about a boss's attack patterns to discern the vanishingly small openings, how to perform the ever-shifting dance between attack and retreat. Playing the game is foremost a process of conversation. One strand of discourse around Shadow of the Erdtree that I found strange was the notion that it is too hard, as the aspect I enjoyed most about the expansion was the way its enemy design was clearly tweaked to respond to the ways players managed to get through the initial game.

Elden Ring is my first FromSoftware experience. Where it differs from the rest of the Dark Souls series is in its open-world scope, and its application of that genre's concepts to the brutal—some would argue "pure" would a more apt word here—combat of the series. Austin Walker, one of the most thoughtful people working in games media, helped contextualize its place within the canon for me. "Despite a decade of messaging from publishers—who smirkingly named the PC release of Dark Souls the 'Prepare to Die Edition'—and fans—many of whom spent years loudly telling new players to 'Git Gud'—this is a series which has always had room for jolly cooperation and finger, but hole," he said. "The great success of Elden Ring is that it shelved all that faux-masochism without trading away the core identity underneath."

The limits and possibilities of the message system, then, make the most sense within the relatively florid world of Elden Ring. Absent syntactical, dictive boundaries, the message system could not exist, at least as anything other than a horrible nuisance. As it does exist, the messages enhance the game's unique texture, the cords of story and gameplay that cultivate and demand that sense of attention in the first place. It's the inherent opacity of the messages that fascinates me. Every player is having a different version of the same experience, and attempting, typically, to communicate the nuances and feelings of that experience to each other across a grainy, imprecise medium.

You are not allowed to write, "These bug enemies' homing projectiles are fucking my shit up, though I have found a way to weave through them by sneaking up on them then staggering them with a charged heavy attack," if that's what you want to express. So how would you communicate it given the limited options? You could be helpful and suggest "try stealth" or "be wary of ranged attack." You could sigh through the internet onto someone's TV by writing "first off, futility," or you could wonder "why is it always resignation, in short, it's like a dream...." You could, in other words, express not a truth but a feeling: the way something affected you, rather than a full rendering of the thing itself. Even the act of deciding to communicate a specific and particularly useful bit of information, in order to coldly farm the in-game benefits, says something about what the player's experience of playing the game was like. You only get 10 messages. Both the choice on offer and the choices themselves, within circumscribed bounds, make the process of communication itself worth seriously considering.

The Bulgarian-French linguist Tzvetan Todorov coined the literary concept of "the fantastic," in his words, "that hesitation experienced by a person who knows only the laws of nature, confronting an apparently supernatural event." I find this a useful frame of reference here. Any message anywhere in the world of Elden Ring could be anything, and you can't know until you read it. They are charged, loose filaments of possibility; any one of them could be someone trying to craft a signpost, or two haunting lines of verse. To return to the way the game conceives of death as a sort of background radiation, the message system ameliorates the frustration and loneliness of all that dying, all that unrewarded attention, and offers the balm of language. It gives Elden Ring's core gameplay loop interactive valence.

If this sounds stuffy, do not worry: For every unsettling or ambitious message, you will see five jokes, often following the absurdist "dog!"-centric throughline or exhortations for players to "try fingers, but hole." The way the joke metagame has evolved, like poetry and language must necessarily evolve alongside each other, is a reflection of the dynamics of contemporary (oft puerile) English. Two years ago, nobody joked (confessed?) "I want to go home, and then edge." I should not chuckle at "fort, nite!" and yet, that joke is only funny because of the limits of its creation. This juvenilia would not glow as it does if it were pulled from the boundless sea of the English language. It's the element of creativity within a set of rules that's alluring. One imagines players in five years continuing to innovate novel ways to be amuse each other; the novelty itself is what is interesting.

I don't think it's overwrought to conceive of this in terms of poetics, either. The oblique truths being communicated through Elden Ring's messages (and for that matter, its mainline story arc) are not those communicated through prose. In a theory of poetry published in 1973, the Finnish linguist Paul Kiparsky opined on the effect of mandatory and discretionary elements of poetry, writing, "When a particular element ceases to be obligatory, it remains as an optional element in the poetic repertoire of a language. In fact, optional elements of form in a poem are more significant than obligatory elements, precisely because the poet has chosen to use them." Kiparsky is 83 years old, but if he played Elden Ring for some reason, I imagine he'd be pointing at his TV and saying "That's right," a lot. That itch, scratched with the roughness of the message system's outlines, is Todorov's fantastic.

See enough instances of "dog?" and it might seem incoherent to think of a player choosing between "laggardly sort" or "old codger" via the prism of the linguistics of poetry, but the message system is functioning on that level. The system's logical (though not necessarily intended) purpose is to be utile, though no matter how you interact with it, messages intensify the gameplay experience. The world of Elden Ring is one that demands care and attention, producing moments of magic along the way. Who wouldn't be fascinated to catch rays of that magic refracted through other players' experiences? Try jumping.