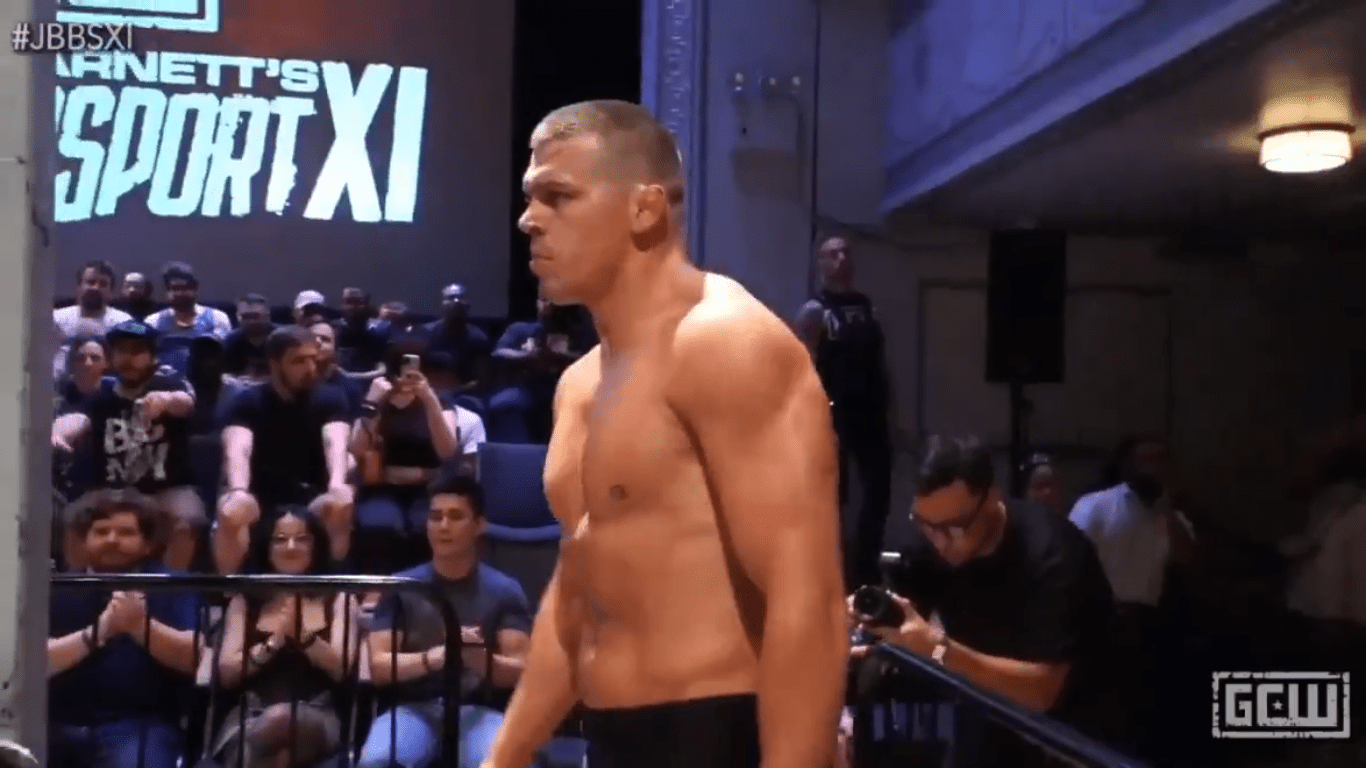

BROOKLYN — They don't make independent wrestlers like Julius Creed, and so it's a bit of a shock to see him towering over the crowd in a criminally overheated gym just a few blocks from where the Liberty play. Unlike the freelance barnstormers and local part-timers typical of the indie scene—often charming and usually relatable: a person you could picture drinking in the bar next door after the show—Creed is unmistakably someone who has devoted his life to being an athlete, as an All-American wrestler at Duke and then as an exclusive WWE trainee for the past four years. Creed stands 6-foot-3, his arms hanging at his sides like giant pieces of medieval weaponry. His torso implies that he never learned about fried food. He carries himself with the easy confidence of a man who cannot be threatened.

Practically drowning in general admission among men sweating off cans of PBR, a blog girl sweating off a can of pink lemonade jockeyed for position and appreciated this sight—not just the presence of a scantily clad and potently masculine body, but one that you're encouraged to stare at for an extended period of time. Most of the heavily male crowd didn't have quite the same reaction, I'm sure, leading to the kind of surreal sense that I was watching a Magic Mike sequel in an audience there for the soundtrack. You're missing the best part! But when Creed showed off his legit strength against his opponent Matt Makowski, lifting him up for a thundering slam, the might of it commanded everyone's attention.

This was Game Changer Wrestling's Bloodsport XI, a first-class indie series that strips away the gimmicks (and the ropes) to present matches that strive for something approximating real combat. Creed was here as an ambassador of sorts, wrestling his first career pro match outside the WWE umbrella. Up until very recently, seeing anyone from WWE, let alone the four wrestlers on this card, in a ring tagged with someone else's branding would have been unthinkable. The company has long loved its monopoly and refused to even acknowledge the existence of any other wrestling. But since the departure of its disgraced ex-dictator Vince McMahon, his successor on the creative side, Paul Levesque (a.k.a. Triple H), has initiated a thaw that's allowed for a bit more talent-sharing between WWE and the littler guys.

I don't buy that they're doing this entirely in good faith—it would be textbook WWE to make a smaller company come to rely on your contracted employees, then end the arrangement—but in the short term, seeing Julius Creed up close at a Bloodsport show was a treat. His work, alongside that of his brother Brutus, fellow WWE prospect Charlie Dempsey, and established star Shayna Baszler, made Sunday night far more notable than a usual indie show and a surprising chapter in WWE's somewhat counterintuitive handbook for developing talent.

It's broadly accepted that the way to get good at wrestling is to do it a lot. Any respectable old-timer will credit their development to hard years spent schlepping around the country and the world, working in different styles with different partners for different audiences. That experience pushes them to develop self-reliance, sharpen their improvisational instincts, and tighten their grasp of the psychology of live performance. Rare is the star wrestler who never had to reinvent himself after his first try, and those favored ones who lasted without paying their dues—Bill Goldberg comes to mind—were invariably protected and permitted by management to play exclusively to their specific strengths.

The best-known versions of WWE thrived on wrestlers who came up outside the company's purview, but in the 21st century they've moved toward an increasingly structured system for bringing along their own prospects. Initially using territorial promotions that functioned as farm teams, for the last decade-plus the hub of talent development has been the Orlando-based brand NXT. Essentially an extension of their "Performance Center" training facility, NXT was previously a low-key streaming show and has aired on USA since 2019, but it underwent a massive reimagining a few years ago.

Under Levesque's initial direction, NXT was money-losing competition to a resurgent indie landscape and an increasingly globalized Japanese scene—the spirit that would give rise to the challenger brand AEW. Unlike the larger-than-life, oft-embarrassing soap operas seen on Raw and Smackdown, NXT was an alternative that trimmed all the fat, better balanced the genders, and focused on intense, crowd-pleasing matches that went beyond WWE's typical fare. The centerpieces of these shows were stars signed out of the indies and from Japan, including a ton of smaller performers who did not at all fit Vince McMahon's main-roster vision of how a wrestler should appear. These were guys who didn't pass the notorious "airport test"—the idea that a superstar pro wrestler needs to be able to turn the heads of strangers while traveling. When they were promoted to the main roster, ascending from Levesque's domain to McMahon's, NXT prospects were typically set up to fail, made to play small roles or fit absurd new personas. It got exhausting, and along with the competition of AEW, the lack of coherent vision stuck NXT in a rut, until "NXT 2.0" launched in 2021.

The 2.0 plan couldn't have been more different, and it made for an even clearer contrast between AEW and WWE. While AEW would sign wrestlers who had succeeded elsewhere, giving them a bigger stage to perform in a way that had worked for them before, WWE directed its resources toward building wrestlers from scratch. In 2.0, they'd sign attractive recent college graduates who looked like wrestlers and then teach them how to do matches—like a record label scouting talent at a modeling agency and putting the most charismatic ones through vocal training.

The new era started as a flop, with a cast of literally not-ready-for-primetime players put on national TV to bluff their way through poorly executed segments, playing phony characters that felt like the remnants of a Gremlins 2 draft. There was a mobster wrestler, and a poker-playing wrestler, and a tennis-brat wrestler, and a sleepy wrestler, and a comic-book-nerd wrestler, and a teacher wrestler, and a skateboarding wrestler, and all of them deserved to fail in relative secrecy instead of flailing on this stage.

But the company stuck with the plan, and they've produced a wrestling show that actually kind of works for a lot of fans. To me it's still lacking the spontaneity and organic creativity that makes you really believe in a wrestler's journey—that makes you root for the person rather than the character—and there's a uniformity to the gorgeousness of the talent that tips into creepy. But NXT today is a colorful and sometimes endearingly goofy TV show with real bright spots. Successes like Trick Williams, Oba Femi, Tony D'Angelo, Tiffany Stratton, and the Creed brothers haven't really known the wrestling world outside the WWE universe, and yet starting at the Performance Center was undeniably the right choice for them. While I still cringe when I see NXT wrestlers moving mechanically from spot to spot as they repeat the performance they've rehearsed all week, there's something to be said for star power.

I remain cynical about both the NXT scheme and the talent-sharing stuff. It reeks of a toxic company attempting to become both a load-bearing pillar of its competition and an insular, self-perpetuating machine that can replenish itself at will. But the shows are the shows, and Julius Creed in Bloodsport was a delight.

I've become a little disillusioned of late with the homogenization of wrestling—people all over working similar versions of the same "banger" match because it's easier than ever to copy ideas you see around the world. These fast-paced, expertly enacted main events can lose that crucial illusion of stakes when they're so smooth and so familiar. Creed, on the other hand, wows me in part because of his limitations. He's not an experienced performer who can adapt the story of a match on the fly, nor is he a natural showman. But he projects raw power and dazzles with his athleticism. He can inspire a reaction even when he does something wrong, like this "mistake" on Raw where his All-American instincts kick in for the recovery, making the moment more dramatic than its original intent.

Watching Creed wrestle for just a few minutes, specifically without the bells and whistles of television or even the indie frills at shows that aren't Bloodsport, was compelling. Rather than a dancer or a wuxia actor, he moved around the ring almost like a bowling ball: Get him pointed in the right direction, and he'll hopefully destroy something.

This KO from NXT’s Julius Creed at tonight’s Bloodsport was COLD as F*CK ☠️pic.twitter.com/DVogveMY1b

— Dark Puroresu Flowsion (@PuroresuFlow) July 28, 2024

Creed's a physically gifted young man trying to navigate unfamiliar terrain. In a sense, he's still very much an athlete, challenging himself as he moves up the ranks of competition. And like an athlete, or unlike wrestling's current crop of international main-eventers, he brings a very real possibility of failure with him into the ring. Whatever training a pro wrestler goes through, their destiny lies in one trait—their ability to inspire belief that what they do matters—that they're not just going through the motions of a scripted performance. Creed isn't seasoned enough to simply go through the motions; he makes me want to see if he's going to pull it off.