Welcome back to Cold Comforts, a recurring column in which Soraya Roberts writes about the grim, harrowing, and downright bizarre movies and television shows that she nevertheless can’t stop watching, over and over again.

The beginning of every episode of Forbrydelsen—translated as The Crime from Danish but adapted to the sexier The Killing in English and for the American adaptation—is a barely visible blonde woman in a slip, running through a pitch-black forest to the frantic beat of a drum. Twenty episodes means 20 times watching that same blonde running for her life through that same forest in the middle of the night, her lingerie torn, her body torn, too. That’s 20 hours of watching a woman, a teenager, about to be killed over and over and over again in an almost a vicarious form of torture. This scene is only the recap at the top of each episode, but it keeps that blonde running through the background of your mind, just as she does through detective Sarah Lund’s, long after it ends. Which is to say, it is impossible to talk about the comfort, the re-watchability of this series, without the uncomfortable acknowledgment that it stems from a girl being terrorized again and again and again.

Forbrydelsen’s effects are now so embedded in the noir crime genre—from the anti-social female detective to the systemic rot surrounding the murder—that it is hard to remember that when it premiered in January 2007 in Denmark (in 2011 in English on the BBC) it had no real TV precedent. Stieg Larsson had already invented grown-up Pippi Longstockings—the Millennium series’ spectrum-orbiting androgyn Lisbeth Salander—but she wasn’t yet on screen. Wallander, the series based on Swedish author Henning Mankell’s Kurt Wallander mysteries, had been kicking around as long as the girl with the dragon tattoo, but like all the detective shows before it, the anti-hero was an old guy. The closest antecedent to Sarah Lund was Jane Tennison, the boozy detective from Prime Suspect who arrived in 1991, but her cases were episodic, the crimes contained, and she was more of an open book. In Forbrydelsen, each episode is a 24-hour segment of the same investigation, with offshoots in three directions: the family, the cops, and the government (the victim is found in one of their vehicles). Producer Piv Bernth believed the moody series that initially puzzled the Danes—there was some confused fiddling with brightness settings when Forbrydelsen first aired on television—but went on to spawn a Nordic Noir boom (notably a mini craze around Sarah Lund’s unofficial uniform: a Faroese sweater) was down to this triptych: “It’s not just about finding the murderer,” she explained.

To Lund it is, though. This is not a well-rounded woman. Her raison d’être is solving this crime and, in that sense, the anti-hero of Forbrydelsen is a stand-in for it. Every time we see Lund, we see that half-naked girl. When we go searching for that Faroese sweater (as I did), we are also searching to be reminded of that half-naked girl. To us, to Lund, nothing else matters. While she has a son, that son is old enough to know his mom “only cares about the dead.” While she has a mother, that mother also knows she will keep fucking up her own life for the sake of a dead girl’s. Lund has a boyfriend, too, a psychologist, but everyone knows where that’s going, even him. When he profiles the murderer, he could just as easily be profiling his own girlfriend. “It turns him on that only he and the girl know where and when it ends,” he says. “To him that’s intimacy. Like a love affair.” Nothing will distract Lund from the object of her, well, attention. She never wears makeup, never changes her outfit—black pea coat, sweater, long-sleeved crew, boot cut jeans, boots, brown leather purse—and she barely eats (when she does who knows what she’s shoveling into her mouth). If I were dead, I would want her on my case. Alive? As someone who is not unlike her when it comes to my own work? I don’t know. This sort of obsession is considered a prerequisite with men. With women, it’s a pathology.

And the gender dynamics of Forbrydelsen are not incidental. Star Sofie Gråbøl worked closely with series creator Søren Sveistrup to mold Sarah Lund, despite others being skeptical of her casting choice. Based on her lengthy career in Denmark, Gråbøl had become associated with gender-appropriate effusiveness—she was the likable hottie. It was her choice to make Lund into the complete opposite. She wanted to play the detective isolated and non-communicative, but the only way she could think to do that, initially, was to act like the men she knew (her character is based on Clint Eastwood after all, Sveistrup’s response to the unrealistic high-fashion, high-sex female detectives he was seeing on television). No one wanted her in a suit, though. They initially went for an Eastwood-style poncho, but Gråbøl had trouble brandishing her weapon in that. So the sweater was floated. Gråbøl recognized it from her hippie childhood in a '70s commune. “It tells of a woman who has so much confidence in herself that she doesn’t have to use her sex to get what she wants,” she explained. With that in mind, a possible affair with politician Troels Hartmann (Lars Mikkelsen, brother of Mads, and fetching in his own right) with whom there remains a frisson throughout the series, was nixed when Gråbøl reportedly responded: “I am Clint Eastwood! He doesn’t have a girlfriend!” (He does smoke, though—Lund chews gum instead).

Despite the lack of sex, there is a seduction scene in Forbrydelsen, and it’s the one that best captures the twisted thrill that comes from watching the show. At the start of the series, Lund is thrown a going-away party because she is set to immigrate to Sweden to start a “normal” life with her boyfriend. As the case progresses, her boss at various points has to convince her to stay in Denmark. The last time he does this, Lund is busying herself packing her things away, ignoring him, implying that she cannot be persuaded this time. But like the bad boyfriend you keep going back to, he knows exactly what to say. With Lund, it’s all about the crime in all its gory details.

“She was still alive when the car went in the water,” he says, his back to Lund. “It takes 20 minutes to fill a car with water. Plus the drowning.”

Lund continues to pack with only a slight pause.

“She was raped repeatedly. Vaginally and anally. The perp wore a condom and took his time.”

Lund stops, she says no.

“She was abused for several hours. Bruises indicate she was held somewhere else before the woods.”

This is the push and pull of a sex scene. The fact is that Lund is turned on by the crime and, because of that, so are we.

Like Lund, Eastwood’s characters after he appeared in the neighborly cowboy series Rawhide were a reaction to it. For his follow-up role as the monosyllabic Man with No Name in Sergio Leone’s spag-boy “Dollars Trilogy,” he chose to convey who he was more through movement and attitude, an approach that would become his signature. “I felt the less he said, the stronger he became and the more he grew in the imagination of the audience,” Eastwood has said.

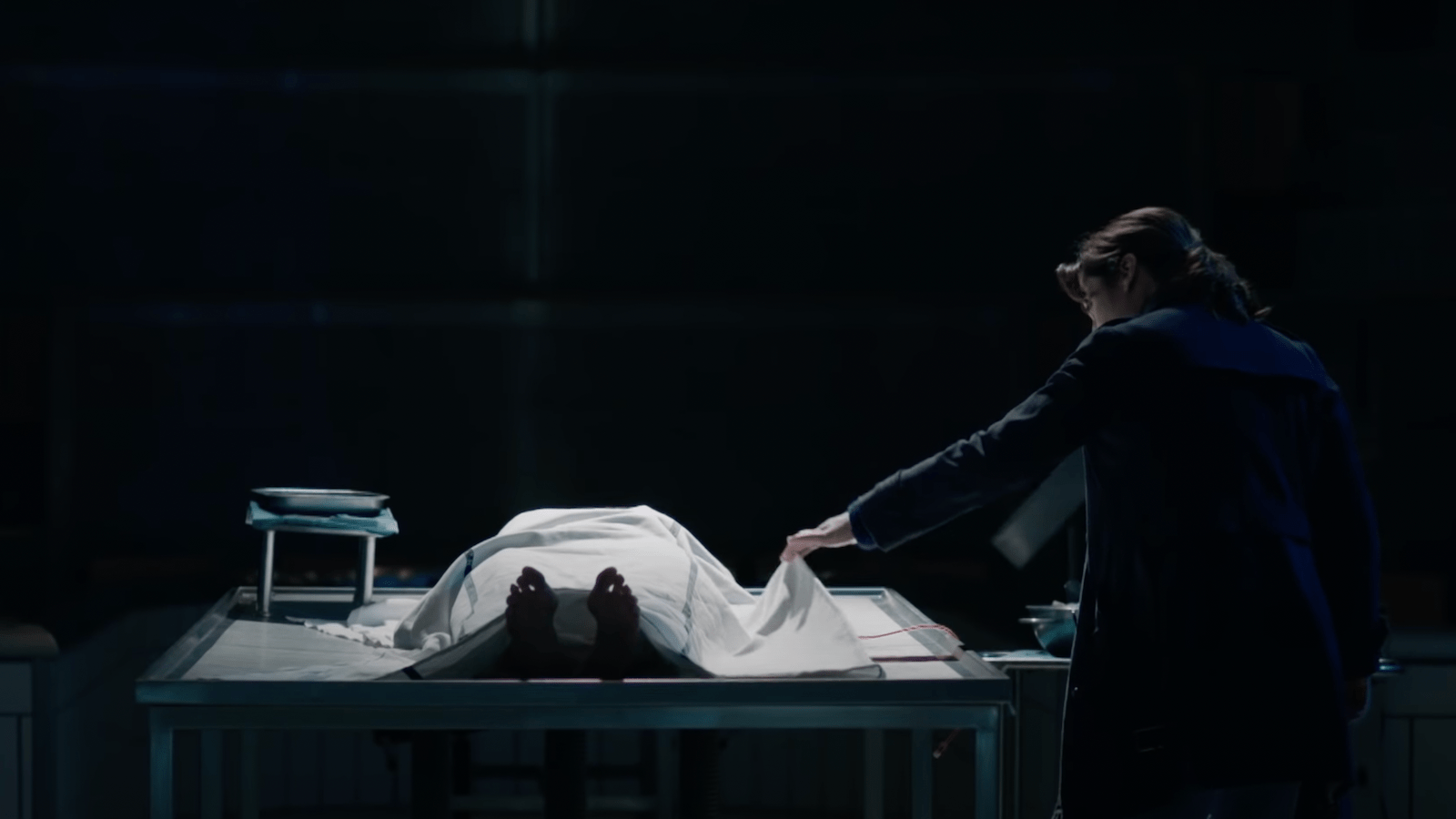

Lund ends up working the same way. An empty vessel for Nordic Noir as a whole, she holds the entire genre inside her, from the grim but expansive scenery of the Scandinavian countryside to the unravelling warmth of the families that live within it to the wavering morality of the political system that holds it all together. But the throbbing heart at the center of it all is the killing of that young girl and the woman who lives to solve it, who only wants to put that girl to rest, who will only rest herself when she is able to. The last episode of Forbrydelsen, once again, starts with that girl running, but concludes with her finally laying still, in a grave covered in flowers, a fitting final resting place for a series in which solace can only bloom out of torment.