Desert locusts are pests of biblical proportions, devastating crops and the communities that depend on them. Left to their own devices, the locusts are solitary and greenish, mostly indistinguishable from any other grasshopper. When the environment is right and the insects' populations begin to grow, however, the locusts can sense their growing numbers and undergo a dramatic transformation into their gregarious phase. They change their color, their body size, and even their brain. And then the locusts begin to swarm, flying in groups of tens of billions that can reach up to 100 square miles, all in search of food.

Although Schistocerca gregaria is one of the world's most devastating pests, "the desert locust has been little studied in the field, and much of its ecology is still unknown," said Koutaro Ould Maeno, a locust expert at the Japan International Research Center for Agricultural Science.

As a child in Japan, Maeno dreamed of becoming an entomologist. After he got his PhD, he looked for jobs where he might study locusts and the problems they cause for people. "But there were none in Japan," he wrote in an email, meaning both the jobs and the problematic locusts. So he went to Mauritania, which is frequently beset by locust swarms, to see locusts in the wild. Maeno, who now calls himself "Dr. Locust," would eventually write a book about his time spent with them.

For the past 10 years, he has tried to record the locusts' behavior in the field. This field research can be difficult, because locusts do not occur every year and can pop up in unexpected places. "They also migrate for a long distance, so it was difficult to find a group of locusts in the Sahara Desert," Maeno said. "Moreover, the field was very hot." But he hopes observing the locusts might lead to new insight into how to control their populations, he said. "I love locusts," Maeno said. "But I have to fight against them to support my life by receiving [a] salary."

By day, the scorching sands of the Sahara can reach lethal temperatures, especially for animals that are not warm-blooded and derive their heat from the environment. One of the most heat-tolerant insects known to science is the Sahara Desert ant, Cataglyphis bicolor, which can withstand surface temperatures of 140 degrees Fahrenheit. But even these ants need to shelter on pebbles or under blades of glass, and must return to their cooler underground homes to let off the excess heat. Many of the insects living there are nocturnal, emerging in the cooler shroud of night to go about their insect business: feeding, mating, and whatever other tasks they deem necessary (except for flying in huge swarms, which, for the desert locust, is strictly a daytime activity).

While camping in the field, Maeno observed that swarms of female desert locusts generally gather together after sunset to lay their eggs in the sand, a process that takes a few hours. But occasionally, Maeno noticed some of the locusts did not start laying their eggs until the following morning, when the sands had already begun to sizzle at temperatures of 122 degrees or more. He wondered how how the locusts managed to perch on such dangerously hot sand for such a long time without overheating. Maeno and colleagues recently published their investigation into how these female locusts stay cool in a paper in Ecology.

Locusts lay their eggs by extending their abdomen into the sand; the temperature less than half an inch underground can be more than 40 degrees Fahrenheit cooler than the surface. At first, Maeno assumed the desert locusts he saw were cooling themselves this way. But as Maeno observed the crowds of locusts laying their eggs during the day in the wild, he noticed almost all the females were mounted by male locusts. This practice is known as mate-guarding, in which males physically guard females to fend off any other of her potential suitors.

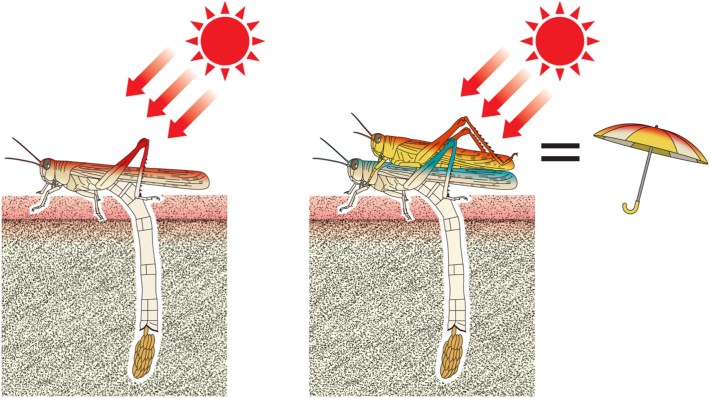

As the sun rose higher in the sky and the sand continued to hear up, the researchers observed that each pair of locusts oriented themselves parallel to the rays of the sun. And when they snapped photos of the locusts with an infrared thermal camera, they found the female insects' body temperatures were significantly lower than the ground temperature. By comparison, the body temperature of the locusts that lay their eggs at night was significantly higher than the temperature of the sand. It seemed the mate-guarding males were acting as a kind of parasol, preventing their chosen female from overheating on the sand.

So while the locusts may also be cooling themselves with their underground abdomens, "this parasol behavior allows them to lay eggs even in harsh, high-temperature environments," Maeno said. He clarified that he does not believe the female locusts are intentionally shielding themselves with the males the way people use parasols to shield themselves from the sun; it's more of a happy accident. "I think that male locusts mount on females to protect them from other males, and the protection from sun rays is just a consequence of that," he said.

Today, most of the research on desert locusts is done in laboratories, perhaps unsurprising given the extreme conditions in which they thrive. But Maeno believes this observation emphasizes the importance of field research. "Of course, laboratory study is essential to understand nature, but we have to go out to see real nature," he said. For now, in Mauritania, the locusts are giving him a swarm welcome.