Do you remember what it felt like to move through the world? I miss being confronted by the unexpected. Not out-and-out anomaly, really—not the time someone smoked crack across from me in the 2 train, not the time a yellow cab made a left turn into the left flank of my body—but just a random grab from the everyday bag of knowns, just enough novelty to require a little processing. I am a simpleton whose whole day can be won by the small victories of urban life. Descending the subway, reading the body language to assess the urgency, and slipping through its closing doors. Breaking a smoothie reverie to holler at a neighborhood pal pedaling by chance. Approaching a busy sidewalk corner perpendicular to someone else, and having to sequence and pace our steps so as to pass without collision. I miss having to think fast, even my abundant failures at it. And I miss days on foot, moving myself through the world, brightening with its mundane surprises and resolving its mundane problems, even when my brain did much of that work without my conscious self even noticing.

But most of the year was spent living in sealed terrariums, which make it hard to find anything buried in your routine. There is no random number generation in a one-bedroom apartment. Every parameter is set and known by you. Spring was so indoors that I got to know every square foot of tile and hardwood intimately enough to want to run away. And so starting in the summer, on the recommendation of a friend, I ran. I would run all year. Not actual bipedal locomotion—I wasn't that desperate, not until later. In this year of enclosure I ran uphill, over and over, while prone on a sofa, until I died. Then I ran up it again. I ran and ran, each time feeling fresher and nimbler. I ran while I ate, ran on the toilet, right before I slept, right after waking. Every run offered the sensation of escape, of a badly needed momentum, of reveling in fresh environs, at a time when even a trip around the block to the grocery store seemed to require the masked efficiency and paranoia of a tactical raid.

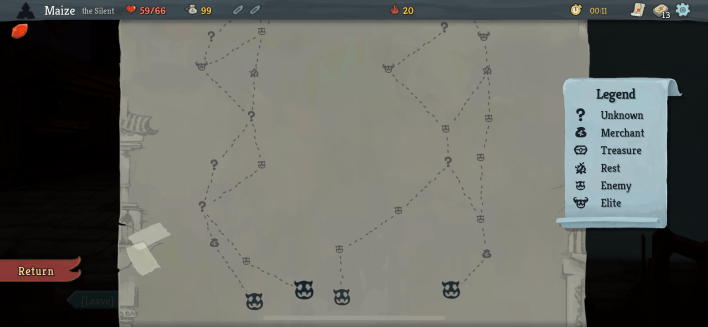

Slay the Spire is a game in which you attempt to ascend a tower that has 50 floors. Every attempt is a "run." You begin by staring at a parchment map that lays out possible routes, and then you chart your course up the tower. Each of those 50 floors holds something for you: a treasure to plunder, a hearth to rest on, a dilemma to resolve. After completing a floor, newly renewed or depleted or a little of both, you head right on to the next one, where you'll be confronted with a different challenge. The usual rituals—get money, kill stuff, grab gear—are enacted towards a simple goal: keep ascending, keep adapting, until you either win or die a permanent death, with none of the solace of a save point.

These are not sprints up an unchanging staircase, ad nauseum. Spire is the lovechild of two distinct archetypes: the deckbuilder, in which you gradually compile a deck of cards from which you draw a slate of possible moves every turn; and the roguelike, in which you crawl across a procedurally generated dungeon that is baked fresh every time you play the game. Because of that, surprise is laced into every layer of the game—in every map laid out, every hand drawn. (If you know the aroma of a freshly ripped booster pack, you know the high.) But it's a bounded surprise. After a few runs, you learn what's out there, and can plan accordingly. You know the enemies you'll face, if not which enemy at which particular juncture. You know the cards you'll draw, if not which card in any particular hand. You know the space of possibilities, but not the specific path you'll carve through it.

My days of twitchy reflexes are over, if I had them at all. I am no longer eager to line up enemy craniums behind a reticle at a dead sprint. I am no longer trying to master the spastic choreography of button mashes that will vault an opponent in the air and keep them ragdolling there with every kick and punch. I no longer crave that frayed, addled mindstate that accompanies real-time combat, against foes sapient or otherwise. But I can, pending closer review, still use my brain. And that is all that Spire asks. Combat is carried out via cards and moves at your preferred pace, with no time constraint, and no demand for dexterity. Which is not to say that it doesn't have its own stressors—the game is brutally hard, for one—just that it doesn't hyper-sensitize my ears to the footsteps of an approaching foe, or cause my thumbs to repeat their accursed phantom dance hours after the fact, or project hallucinated gameplay against my closed eyelids. I do dream of this game, but that's, ah, good, actually.

The genius of Spire is that every run begins at a crawl. Your starting deck is loaded with middling attack and blocks and a single trick or two. As you proceed through the tower, you refresh your deck with new cards, and excise the unwanted ones. The toughest enemies leave you relics, which are hard-won trinkets that make your character stronger in extremely narrow ways—"Every time you receive five or less damage, reduce that damage to one," or "Every tenth card you play, draw a card," and the like. Spire is about understanding the interplay between the cards in your deck and the relics you amass. You learn that there are no bad cards, only bad decks. Diagnosing what a deck needs is a rich and rewarding art, asking you to cast aside the crusty spreadsheets and work off raw intuition. Put your ear up to the screen, hear your deck hum: Does it need more blocking? More card draw? More knives? In time these answers come as naturally as putting one foot in front of the other. One floor you look up and your deck has what it needs to work: an engine. An artfully assembled deck can put its wielder into a fugue state, liberated to plow through foes behind that whirring engine. A good run has your sprite running up the spire mellow, unencumbered, god-like.

That is, until I became acquainted with the late-run faceplant. After you win your first run, the game wheels its actual challenge from behind a curtain: Ascension Mode, 20 different ways to make your run harder. Ascension n + 1 has all the hardships of Ascension n, plus a fresh one: gold is scarcer, or a useless curse card clutters your deck, or (deep breath) a final boss awaits after the final boss. By the final few Ascensions, winning is a punishing prospect, requiring you to survive at perilous margins, squeeze every possible drop of synergy out of your cards and relics, use your health as an expendable resource, make long-term sacrifices for short-term survival (and vice versa). Under these pressures, you stumble upon more and more degenerate strategies: an exponentially swole punch, an impenetrable wall of ice, a bellyful of poison. At the hardest level, I could go a dozen runs without a win. Somehow my appetite for the pain never abated, and I can locate exactly why. Spire keeps demanding that you find new ways to beat it, all the more so as the difficulty ratcheted up.

There is no One True Way to defeat the Spire, no fail-proof technique that you asymptotically approach with each playthrough. Because of the ever-shifting nature of the map and card offerings, the lessons of your last run may not be directly applicable to the next. Every run makes running easier, but only in a more holistic sense. Playing a lot of Tetris, say, gets you better at quickly recognizing and manipulating shapes, in a linear way. Playing a lot of Spire builds up something subtler: a wisdom base to draw on, banked memories of all the times you ate shit and why. What you develop by playing the game this obsessively isn't so much a specific approach as an awareness of and openness to all possible approaches, and the flexibility to toggle between them whenever the whims of randomness demand it. It's learning how to think on the move. I am not lying to you when I say that the dozens of hours holed up playing a card game reminded me of what it was like to live an actual life.

So I was going to beat those 20 Ascensions, with all the characters—the sad soldier who hits hard and regenerates himself, the skull lady who plies knives and poison, the defective robot that juggles elemental orbs—each of which immersed me in a new card and relic pool. I even found myself, beyond my grimmest expectations, tuning into Twitch streams by the world's best player, a jovial German who plodded through four-hour runs with near-perfect judgment. I had to mine every insight there was, take everything this game had to offer. How could I resist that temptation? Who was I to pass up feelings of forward motion, improvisation, novelty in a year where all three were so scarce? How could I turn away from the satisfaction of clearing all 20 hurdles? Or the impulse, after a successful run, to pull my brain out of my skull and give it a loving scritch?

Because no one should rest easy with one coping mechanism, the running became literal, after I hauled myself across the country to remember how nice it was to be outside. On a lake trail fringed by evergreens and big ferns, I learned to love what I hated most as an asthmatic kid and a patellar-tendinitis-having adult. (Shoutout to physical therapy; I can measure my age in the number of peers who love physical therapy.) All places in the world have weather, but the Pacific Northwest has so much of it that every run took me down an apparently new map. Morning rain had pitted the earth with puddles and exposed tree roots. November sent the maple leaves tumbling, softening and slickening the footfalls. The sun had returned from exile to bake everything dry. Or there was just mud, mud, mud to squelch through, with a gratitude that only this plague year could have instilled in me.

No two runs were the same, but what they had in common was the feeling, over the first half-mile, that I was the mummy of Ramesses II, unbandaged and loosed upon the woods at a light jog. And there was the occasional aborted run, which taught me to listen to aches. But every other time, the lungs went to work, the stiffness warmed itself out of my joints, my body tacitly adjusted to conditions, miles glided by, and I felt I could do all this indefinitely. I recognized this feeling, in a perverse and backwards way, from all those hours of clicking cards on a screen: The engine was on. You did the work to set yourself in motion, and so can now just enjoy the payoff. There was a new post-run feeling, worthy of its own addiction: perfect vacancy, as if someone had scooped out my consciousness with a melon baller, and the pleasure of having moved a stationary self over so much ground and back again.