It’s Hagler vs. Hearns on the chessboard in Astana, as Ding Liren and Ian Nepomniachtchi have reached the halfway point of their 14-game world chess championship match, with Nepo leading by a full point. We’ve been treated to a barn-burning first half of the match, with some mesmerizing chess leading to an incredible five decisive games (including the last four in a row). The action on the board has only been matched for pure theatre by the players’ incredible character arcs off of it.

Thrice has Nepomniachtchi taken the lead in the match, with Ding thus far scoring two equalizers. Let’s recap the first seven games, where we’ll go with bold text for moves which actually occurred in the games, and italics for hypothetical variations which did not. If you want to catch up with our two competitors, check out my match preview.

Game 1

Ahead of Game 1 of the match to determine the 17th world chess champion, we gained some insight into which elite players are assisting our two combatants with their opening preparation. It was revealed that world No. 13 Richard Rapport and world No. 25 Nikita Vitiugov are seconding for Ding and Nepomniachtchi respectively, and that retired former world champion Vladimir Kramnik is heading up Nepomniachtchi’s team. The long-standing practice of top players assisting others with their preparation for important tournaments is unique to chess: it would be like Stefanos Tsitsipas getting knocked out at Wimbledon and proceeding to work on strategy with Carlos Alcaraz for the rest of the tournament.

Nepomniachtchi had the white pieces in Game 1, and he opened with his usual 1.e4. Ding replied with his usual 1…e5, and the players gave us a line of the Marshall Attack in the Ruy-Lopez, or “Spanish," Opening. Although this was expected territory, Nepo found some early finesses within the familiar system: he went for a delayed exchange variation by trading his light-squared bishop for Ding’s c6 knight on move 6, and followed up by protecting his e-pawn with his rook instead of his d-pawn (a move so rare that present-day poker player Magnus Carlsen tweeted that he had no idea it existed):

Nepo (playing very fast) nursed a slight advantage into the middlegame, with computers at one stage showing he had a full-pawn advantage. Ding, meanwhile, played a few marginally inaccurate moves and looked noticeably out of sorts: his body language was nervous and timid, and he was spending a lot of time thinking in the rest area rather than at the board.

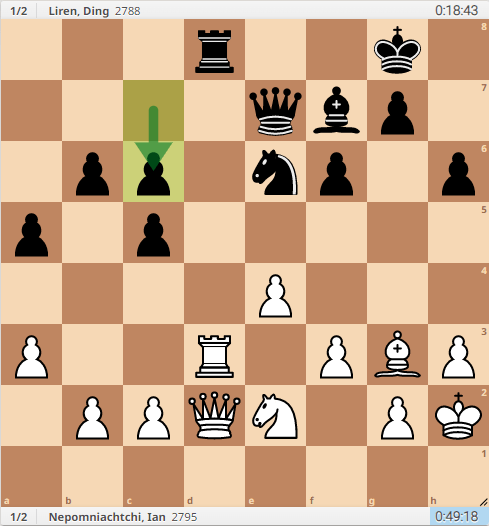

Emblematic of Ding’s muddled mindset was his decision to push his c-pawn on move 26:

The idea behind this move is presumably to prepare a pawnstorm on the queenside (or at least to create that threat, inducing Nepo to react), but it seems Ding had misevaluated where the most important action on the board lay: after a trade of rooks and queen to f4, White’s queen and bishop controlled the dark-squared b8-h2 diagonal, ready to invade the position and pick off Black’s queenside pawns, with that c-pawn no longer anchoring a chain of defense.

Ding faced some nervous moments in the run-up to move 40—at which point the players are given an extra hour on their game clocks, in addition to the two hours they start the game with—but managed to achieve a favorable trade of queens on move 37, and although Nepomniachtchi did indeed eventually manage to win Black’s a-pawn with his bishop, Ding had calculated the variations well enough to ensure that the advantage was neutralized by virtue of his well-placed king and mobile minor pieces. The players agreed to a draw on move 49 with each side down to a bishop, knight, and five pawns.

The real story of the day was Ding’s performance at the post-game press conference. He openly stated that during the first part of the game he felt there was something wrong with his mind, as he struggled to calculate at the board due to the pressure of the match. He revealed, totally unprompted, that he hadn’t prepared anything for the opening on the day prior to Game 1, because, as he put it, “I’m struggling with my feelings, my emotions.” He also revealed that he’d changed hotels prior to the start of the tournament because he didn’t feel comfortable in the plush St. Regis (the site of the match). Ding even confirmed that the reason he took more than two minutes to answer Nepo’s first move 1.e4 with 1…e5 was indeed because he was still deciding between different options right up until he made his move.

It was fascinating to watch: not only did Ding not give us any of the usual, stilted, PR-ified athlete-talk, it seemed that he was genuinely unaware that that’s a thing, or that there might be a reason to offer anything other than brutal honesty. He’s got personality, too: he said that he likes having Richard Rapport with him in Astana because it allows him to practice speaking English, and they listen to a lot of '80s music together. Adorable!

Game 2

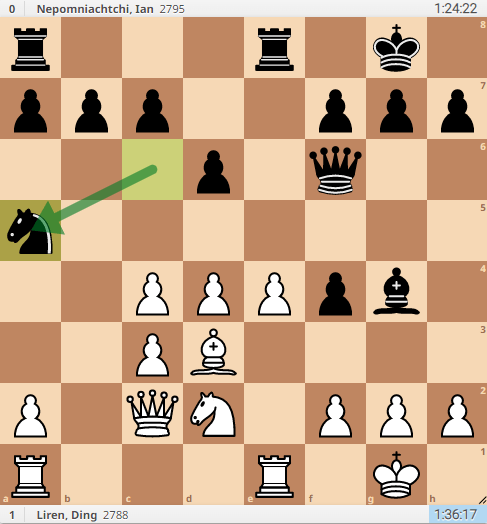

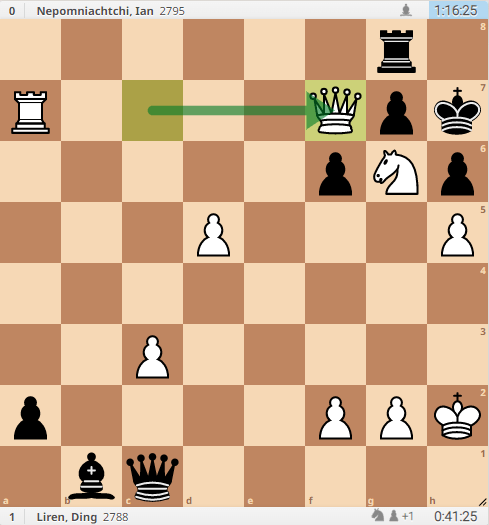

Ding Liren signaled early in Game 2 that he came to Kazakhstan with a couple of new arrows in his quiver: after starting with his usual 1.d4, on move 4 he sprung a move never seen before between high-level players: 4.h3?! in a line of (what turned out to be) the Queen’s Gambit Accepted. It was a move that had his second, Rapport’s, fingerprints all over it, since the Hungarian/Romanian is known to come up with offbeat opening ideas. Already Nepo was forced to calculate a move he was not prepared for, and initially considering that 4.h3 made no direct impact on the position, he played as if one tempo up, throwing his pieces into the center off the board and attempting to strong-arm the position.

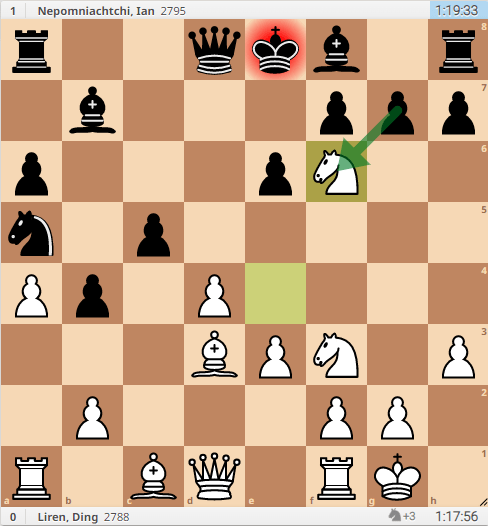

The tide first started to turn against Ding on move 12, when, after spending 33 minutes thinking about knight takes on f6, check?!, he had apparently not even considered Nepo’s response:

Black’s g-pawn recaptures the knight, and suddenly Nepo’s plan is clear: the g-file is open and the position is screaming out for an attack on Ding’s king—Nepo can castle queenside, bring a rook to g8, and attack. Only White’s knight on a5 is presently out of the action, with all of its other pieces able to be developed into attacking positions with a single move, and the queenside pawns already cramping Black’s pieces. Ding had apparently not even considered that Nepo would do anything other than recapture with the queen, another indication that his head was not yet fully in the game.

The situation became critical quickly, with Black creating tactical openings against the White king. Ding made several inaccuracies, passing on opportunities to create counterplay or to kill off a few of Black’s attackers at opportune moments. By contrast, Nepomniachtchi didn’t miss a step, and correctly sacrificed the exchange on move 20:

Black’s rook takes on g5!, knight recaptures on g5, and then the black knight takes pawn on d4!

Ouch! Now, there are spotfires all over the board: White’s queen needs to duck out of the forthcoming discovered attack by the d8-rook, its d4 pawn will soon be eliminated, and Black’s c-pawn looks like it is marching toward an inevitable promotion.

Nepo was in the zone, playing blindingly quick, and Ding wasn’t able to keep up, spending tons of time thinking about each move and eventually losing his battle against the clock as much as against his human opponent. He was once again spending swathes of time in the rest area, wearing a huge old jacket over his formal gamewear—it’s getting down to zero degrees Fahrenheit in Astana!—and simply didn’t look like he was coping with the pressure.

On move 29, with Ding clinging on to the life raft and needing to make 11 more moves in under one minute, he resigned in the following totally dominated position:

Try to find a safe square for the d4-rook!

It was a game where everything went right for one man and nothing went right for the other. Finally, after being swept 4-0 by Magnus Carlsen in 2021, Ian Nepomniachtchi has won a game in a world championship match. His opponent had had a nightmarish start to his first title campaign: more nerves than a copy of Gray’s Anatomy, and now down 1-0 after losing a precious game with the white pieces. At virtually every juncture in Game 2 where Ding was required to make a decision, he decided wrongly, and things were not looking good.

Game 3

After the first rest day, Nepomniachtchi opened up Game 3 with a curveball: 1.d4, a relative rarity in his oeuvre and a deviation from his White games against Magnus Carlsen in 2021 (he played 1.e4 five times and 1.c4 once). Ding admitted he was not expecting d4, and opted to play a main line of the Queen’s Gambit Declined.

Ding soon achieved equilibrium out of the opening with the black pieces. With the spate of decisive games in the first half of the match, there’s no need to focus on this game for too long: we saw a nuanced early-to-middlegame following the opening where Ding briefly thought he might be able to seize the initiative, but in the end a fairly workaday draw by repetition was reached on move 30.

The fact that Ding had managed to keep the game under control signified a huge improvement from the first two games, and he looked visibly more comfortable, for the first time spending a lot of time at the board, rather than hiding away in the rest area. Once again displaying his uncommon candor, he explained at the press conference that a friend had helped him come to terms with the fact that he wasn’t handling the pressure of the match adequately. After three games, it seemed as though Ding Liren was finally ready to start playing.

Game 4

Having seemingly steadied the ship in Game 3, Ding opted to open Game 4 by playing the English Opening 1.c4 with the white pieces. It wasn’t a huge surprise that he might try something different with White after his Game 2 novelty achieved nothing and preceded a bad loss, but playing c4 against Nepomniachtchi must have brought back some painful memories, due to their game in Round 1 of the 2022 Candidates Tournament (the tournament through which both players qualified for this match) also starting with a Ding c-pawn push and ending in a Nepo win.

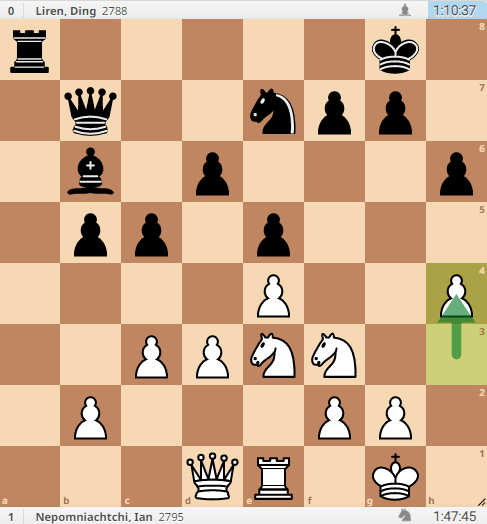

Ding was playing smoothly in the opening, barely stopping to think until move 13, and two moves later he sacrificed a pawn for positional compensation:

After Nepomniachtchi’s loose knight to a5?!, leaving it far away from the action, Ding hit back with pawn to c5, and after Black’s d-pawn captures on c5, pawn to e5 hits the Black queen, forcing her to retreat, with pawn d5 to be followed next move by pawn to c4, and all of a sudden White had a massive grip over the center of the board.

Ding continued to buttress his pleasant position, and although Nepo was forced to solidify rather than attack, the situation was under control into the middlegame. But then, on move 28, Nepo showed that his blunderous ways are not fully behind him, and while playing far too quickly he erred with the careless knight to d4?? Here’s your chance: find the winning move for White!

Ding only required one minute of thought to correctly sacrifice the exchange with rook takes on d4!, and just like that, the game was virtually over. The point is that after Black recaptures with the pawn, White’s knight jumps to b3, ready to win that pawn on the next move, and although White is temporarily down material, it has a dominant position: the white pawns control the center, Black’s rooks are biting on granite stuck on defensive duty, and White’s queen is far more mobile than her regal counterpart. Poor Nepo stated after the game that he hadn’t seen this continuation, and he was helpless to fight back once it appeared on the board.

This was the kind of position that elite players dream of, with Ding able to choose from a number of winning plans. Supported by virtue of the bold push of his g-pawn, Ding was able to get his horsey to f5, push his two central pawns, and then jump the knight to d6, forking Black’s queen (by then on f7) and e8-rook, winning back the exchange with a dominant position.

Nepo could only shuffle his pieces around in the hope that Ding would slip up and allow a comeback. The slip never came, as Ding gleefully won back a pawn to equalize the material balance, and maneuvered his way to the gorgeous final position:

This one had me honking like a damn goose: queen to f8!, and Nepo resigned. The sequence to follow would have been beautiful, with Black being forced to pick its poison: either Black’s queen captures queen, in which case White’s e-pawn captures and promotes to a knight!, forking the king and rook and leaving White a full rook up; or Black’s queen captures the pawn, in which case rook e1, check skewers and wins the queen; or (the prettiest of all), if Black plays rook g8, White can sacrifice the queen with queen takes g8!, and after Black recaptures, follow up with rook d8!!, with the pawn promoting on the next move. Mwah!

It now seemed as though momentum was firmly on Ding’s side: he was clearly back firing on all cylinders, picking up a stylish and professional win to level the match, and even revealing in the press conference that he’d moved back into the hotel at which the match is being staged. Nepomniachtchi, meanwhile, must surely have been seeing visions of his 2021 capitulation: he’d again blundered the house in one move, just as he’d done three times in the last four games against Carlsen. If Nepo couldn’t find a way to get back on track, he risked being swept out with the tide once again.

Game 5

After another rest day, Nepomniachtchi returned to his trusty 1.e4 with the white pieces. We had another Spanish Opening, but the players deviated from the line seen in Game 1, with Nepo retaining his light-squared bishop and pushing his d-pawn early. Nepo used only five-and-a-half minutes for his first 22 moves, as he was either comfortably within his preparation, or (as he is wont to do) bluffing that he was.

Nepo then spent 21 minutes on his next two moves:

Here, h4 and subsequently h5 laid the groundwork for a rather adagio kingside attack which, although the position remained balanced, eventually pressured Ding into a mistake. In the meantime, Nepo’s minor pieces remained superior to Ding’s (although that bishop on b6 would find some oxygen after Black’s response c4 pawn-push).

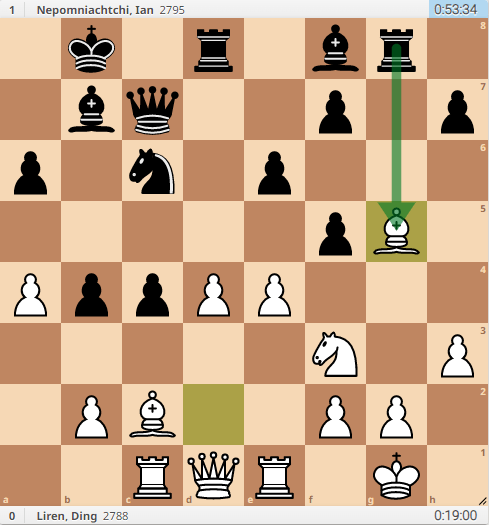

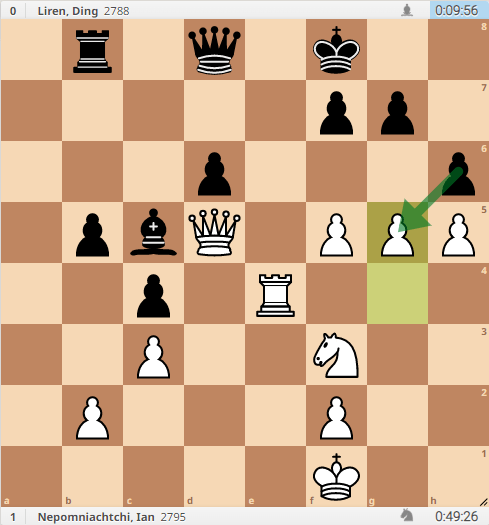

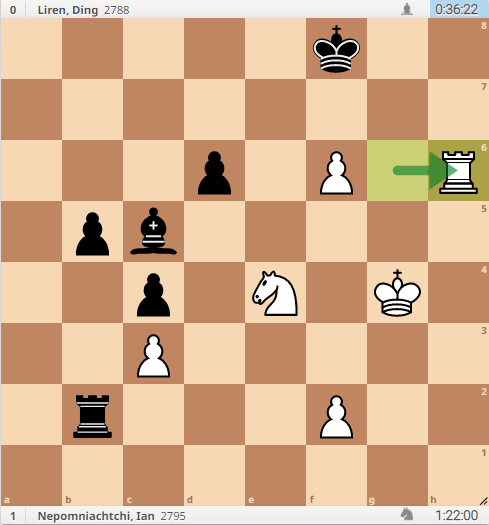

It was on move 37 when the silicon says that Ding went astray:

Pawn takes on g5? turns out to have been an error (better was queen d7, both g-pawns take on h6, then if White plays f6 Black has the resource queen h3, check, where the queen is in White’s house and can hope to nettle White’s king). After the response (rook to g4), Black can’t protect the g5 pawn because of the threat of the gorgeous knight to h4!. When the pawn can’t take the knight because of pawn to h6!, Black must choose between allowing that pawn to march up the board and get promoted or capturing it with its g-pawn, allowing rook to g8, check, and a swift death.

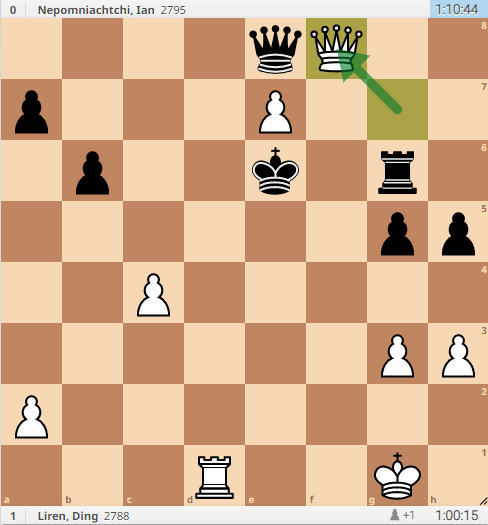

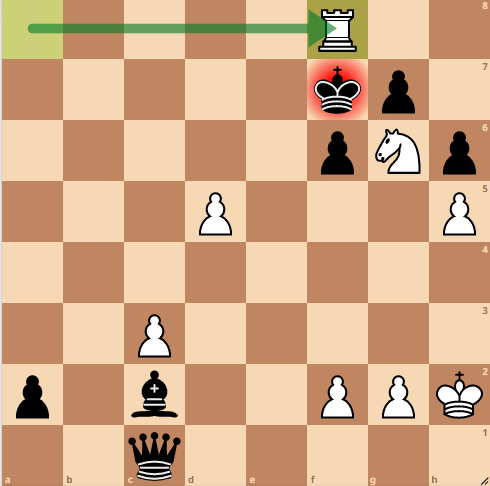

White could therefore freely capture that g-pawn, giving it a kingside majority. Nepomniachtchi boldly responded to a rook-check on a1 by stepping his king forward onto the e-file, confident that his knight could block any further checks from the black queen. White was able to force a trade of queens on move 43, and Ding resigned five moves later:

Although material is equal, White’s position is overwhelming: the black king has got to run from the threat of knight g5 followed by rook h8, checkmate, and in the meantime White’s f-pawn is rolling.

This was yet another surprising momentum swing, with Nepomniachtchi seemingly having addressed his tendency to tilt after a loss, and with Ding crashing back down to Earth after having squared the ledger in the previous game. Is this a new Nepomniachtchi, capable of digging deep and avenging losses? Were Ding’s brief flashes of brilliance only temporary? Ding seemed settled enough in the postgame press conference, but were those doubts starting to creep back in?

Game 6

In Game 6, Ding returned to 1.d4 with the white pieces, and after 1…Nf6 2.Nf3 d5 3.Bf4 we had the first ever appearance of the London System in a world championship match. Boooooooo! The London is considered one of the lamest openings in the entire chess rolodex: it usually leads to boring, symmetrical positions where neither side has an obvious way to pressure for an advantage or to spice things up for the fans. Nevertheless, it’s a feature of Ding’s repertoire, and he later said that he (again!) only decided to play it on the morning of Game 6.

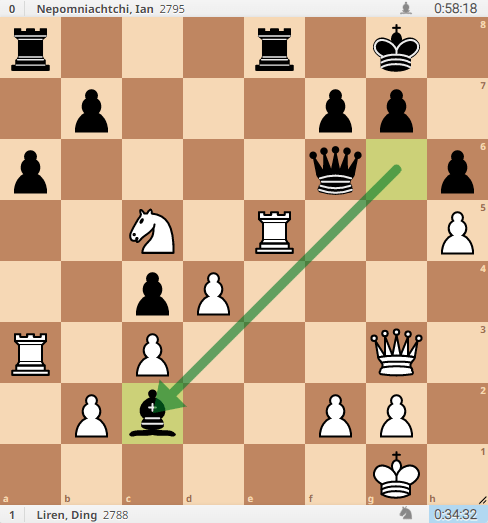

It appears that Nepo didn’t quite employ the correct defensive set-up, and Ding was clearly more comfortable in the nuances of the pawn structure that followed. Nepomniachtchi rejected a queen trade on move 20, and later criticized his move bishop to c2:

He says that he should have played bishop to d3, protecting the c4-pawn. Instead, play continued with knight takes on b7, queen to b6, and then knight to d6 laid a little trap: the black queen can’t take the undefended knight, lest White play rook takes on e8, check, winning the black queen on the next move. After a trade of rooks on e5 Black grabbed the b2-pawn, and White played rook to a5, a move that Ding later identified as the critical move of the game, and had a very unusual but highly effective flank of heavy pieces on the fifth rank.

Black had counterplay in the form of its passed a-pawn, but it was White holding the better cards: its pieces were menacing the black king, its knight was far better than Black’s bishop, and the black rook was tied down defending on the back rank.

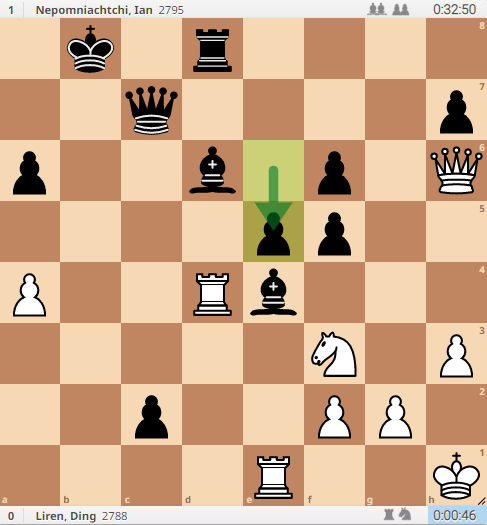

Despite Ding’s positional advantage, Nepomniachtchi was playing way too fast, declining to spend chunks of time giving the position the deep analysis it really required. Yet again in this match, it seemed that a player’s mindset was negatively affecting the position on the board. Ding continued to play all the correct moves, and Nepo let the position slip to the point where White was clearly winning. From there, it was just a matter of choosing the correct winning plan—for one thing, with the white king having moved to h2, the white queen had to stay on the g2-b8 diagonal, preventing the black queen finding a perpetual check by toggling between c1 and f4 and thus salvaging a draw—and having reached the time control with four minutes to spare, on move 41 Ding played one of the most stunning chess moves I’ve ever seen:

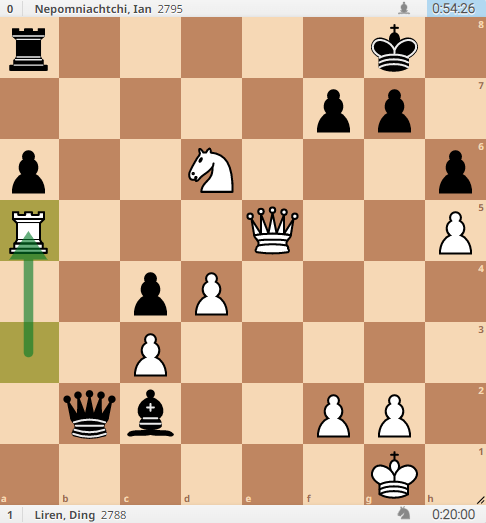

Pawn to d5!! is a move that will be featured in textbooks 100 years from now. Now, you might be thinking, as I did when I was following this game live: So what? The pawn is one square closer to promotion, looks like it’s nothing special. Just you wait—the finish is as beautiful as the smile of a baby.

Black counters by playing his strongest card in pushing his pawn to a2, but then White plays queen c7!, threatening knight to g6, check, and mate on g7 the next move. Therefore king h7 is forced, and after knight g6 and rook g8 (defending the g7-square), White plays queen f7!!, and Black resigns.

Why? Given the chance to play on (say, after Black plays bishop c2) White would sacrifice the queen with queen takes on g8!!, and after the king recaptures, we see rook a8 check, king f7, and the beautiful rook f8, checkmate!!

Now we see the point of that pawn move: the d-pawn controls the e6-square, completing the encirclement of the Black king, leaving it stranded and mated on f7. Ding had seen this variation from afar, calculating from six moves out that he needed to control one more square to make his attack complete. Go on—scroll back up to the position after d5 and see if you can picture this finishing pattern. Oh, my word. A beautiful mating net deserving of the “I’m not a rapper” reaction. Just gorgeous stuff.

An amazing finish to a great game. Ding had now equalized the match for a second time, and once again looked to be at home on chess’s biggest stage. Nepomniachtchi (perhaps prone to exaggeration) called it “one of my worst games ever,” stating that “nearly every move was bad.” Now, another rest day, with both players’ heads surely spinning from the twists and turns in the first half-dozen games.

Game 7

In Game 7, Nepomniachtchi opened with 1.e4 with the white pieces, and, after a dramatic pause, Ding responded with 1…e6, the French Defense! Ding has clearly come to Astana with a cornucopia of new opening ideas, since according to the database he had not played the French in a competitive game since 2013(!), although his best bud Richie Rapport does play it and was revealed to have prodded Ding to try it in this game. It was also the first appearance of the French in a world championship match since Viktor Korchnoi played it twice for two yogurt-infused draws against Anatoly Karpov in 1978.

From this inauspicious opening, we got one of the craziest games in memory.

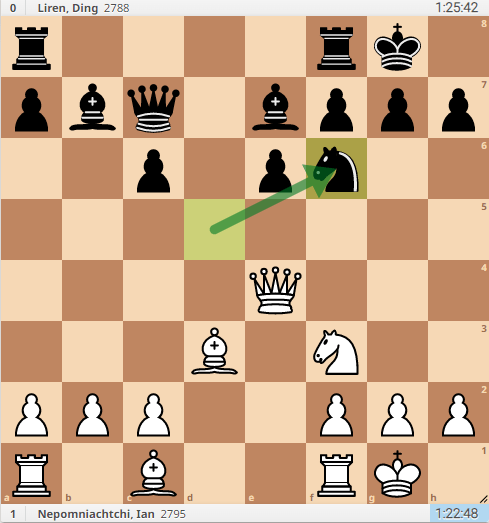

In a standard opening phase, Ding made the first inaccuracy on move 13, with knight to f6:

He’s got to defend from checkmate on h7, but in the long-term that move seemed to open the door for White to place the squeeze on Black’s position: the white queen came to h4, leaving the mate-in-one threat dormant and leaving the black knight glued to the spot, while White could continue to amass its pieces on the kingside. (Better was simply g6, where the light-squared bishop’s communication to the h7 square was forever severed.)

Nepo continued to build a suffocating attack on Ding’s king, and while the supercomputers claimed the position to be equal, it looked absolutely nightmarish for a human to play, with White’s pressure on the black king only building with every move. Worse: Ding was in time trouble for virtually the entire game, having burned half of the two-hour allotment granted to the players for their first 40 moves by move 15, and being down to only 23 minutes at move 20.

He was nevertheless finding all the correct moves, showing why his calculation abilities are held in such high esteem: he brought his rook from a8 to d8 on move 16, threatening to kill off White’s light-squared bishop, and then found the important resource of stationing that rook on d4, where it temporarily bothered White’s queen.

It’s never easy to play a sharp position (i.e., one with lots of complicated tactical opportunities to calculate at every juncture), and especially not in a world championship match while low on time. Ding calculated an exchange sacrifice on move 22, where in the below position knight takes on f4 was followed by the bishop and then two rooks recapturing on that square, and then black’s bishop takes knight on e5, and white’s rook swings across to h4, renewing the threat on h7.

To give a sense of what the players had to calculate at each position, consider that instead of recapturing white’s knight with his bishop, Nepomniachtchi could have played rook takes on f4!, and after bishop takes knight on e5, White could go for a stylish sacrifice with bishop takes on g6!, capturing the d4-rook next move, and then the black bishop can’t capture White’s f4-rook because of the threat of bishop f6! and a swift checkmate on h8.

Ding was navigating the complications, showing why he’s perhaps the best calculator in the game of chess, and it was starting to look like the players had reached a position where White’s attack had been defanged, incredibly leaving Black as the one with the long-term advantage, given its superior kingside pawn structure. We looked set for an epic late-middlegame, where Ding would have the opportunity to re-establish control in a titanic arm wrestle.

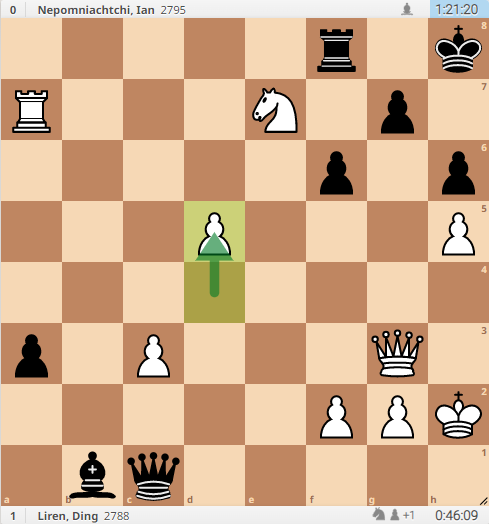

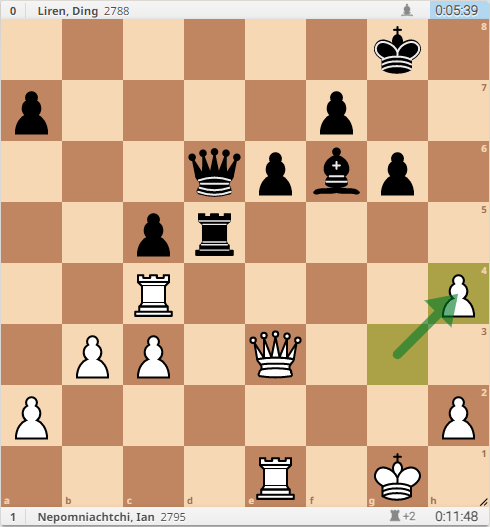

And now, it’s time for another edition of What To Do In This Position? Here, it’s Ding Liren to move with the black pieces. It’s his 32nd move, and he’s got five minutes and 39 seconds to make these final nine moves before he gets one additional hour after move 40. Here’s the position, take a guess—what did Ding Liren do here?

Ding did … nothing!

He froze. He stared at the board, fruitlessly calculating. For a full five of his final five-and-a-half minutes in the most important game of his career, it looked as though someone had unplugged the second-best chess player in the world.

Watch the replay of those utterly excruciating five minutes here, if you want to stress yourself out. Ding cracked, plain and simple—after having so impressively navigated the hugely complex positions to that point, he became overwhelmed by the moment in the best position he’d had at the board all day, too paralyzed by nerves to make a move, when chess engine Stockfish 11 gives five very straightforward options which are all absolutely fine for Black (simply king g7, for example).

And just like that, Ding had thrown the game away in the most painful way possible: he’d burned so much time that he would have none left to consider his next moves (and barely enough time to physically make them), a sure recipe for disaster.

The move that Ding did eventually make after this interminable tank turned out to be a mistake: after rook to d2, Nepo easily found the refutation rook to e2. Forced to move instantaneously without any time for thought, Ding then predictably blundered with rook d3?, where White could collect the c5 pawn, and Black’s inroads to the white king could be parried by the white rook stacking on the f-file, hitting and winning the f7-pawn and the game. Ding didn’t even manage to get to the time control, resigning after he blitzed out his 37th move, with only three seconds left on his clock.

So, what happened? Ding said in the press conference that he realized that there was a counterpunch to the line he had intended, and was trying to calculate an alternative: “I started to think again, and I couldn’t find any way to continue.” That statement reveals a player not at the top of their game: it was an error to spend that long calculating moves which he would ultimately have no time to play, and poor-quality calculation not to find one of five decent continuations which were available.

A bonkers end to a great game, to round out an utterly incredible start to this world championship. I’ve got whiplash from all the twists and turns in these first seven games—if you’re new to chess, know that this isn’t normal! High-level chess can be a draw-fest, and we’ve now somehow seen five decisive games out of seven. This is one of the most gripping competitive events in any field that I’ve ever followed—a spectacle where the unbelievable competitive play is somehow being overshadowed by the humanity it is revealing in its participants.

I’ve got one question at this stage of the match: Just who are these guys? From Nepomniachtchi’s point of view, is the fact that he has twice bounced back from a loss with a win indicative that he’s developed a resilience that he did not display in the 2021 world championship match? Or does the fact that he has blundered away two games show that he’s the same as he ever was, liable to crack under pressure? And as for Ding—does he really believe that he belongs here? We thought he had defeated his early match nerves by showing that he can play brilliant chess on this biggest of all stages, but his total meltdown in Game 7 revealed a man with an unsettled psyche. Which versions of both will we be seeing in the second half?

I’ll be back to recap the final seven games at the conclusion of the match in about two weeks. See you then, folks!