The saga of John Rogers concluded on a briskly cold afternoon in December 2017, when the sweet-talking scammer from Arkansas turned to speak directly to his teenage son inside the Everett Dirksen U.S. Courthouse in Chicago.

“I screwed it up,” he said.

His thick beard turned to gray, the hulking sports-memorabilia dealer alternately rambled and sobbed for nearly 45 minutes. He confessed that he’d been lying for years—to investors, partners, collectors, the FBI, and his own family—and recounted how cocaine had taken over his life.

He pleaded for leniency from U.S. District Judge Thomas Durkin, promising to pay back the millions he owed to his victims. “I don’t deserve a break,” he said, “but I’m asking you for one.”

His words didn’t work this time. Judge Durkin sentenced Rogers to 12 years in prison and ordered restitution of more than $23.5 million.

“You literally told thousands of lies to honest people to have them part with their money,” Durkin concluded, describing Rogers’s decade-long pattern of deceit as “breathtaking” and his actions as “monumentally stupid.”

The rise and precipitous fall of the man described as the “Madoff of Memorabilia” devastated the tight-knit community of North Little Rock and roiled the sports collectible industry. But Rogers set himself apart from other dealers by amassing the largest privately owned collection of vintage photographs by purchasing the morgues of cash-strapped newspapers like the Denver Post and the Chicago Sun-Times, as well as the archives of the nation’s most acclaimed photographers, some living and some dead.

Journalists flocked to North Little Rock to tour Rogers’s 24-hour, state-of-the-art scanning operation and to gape at the endless rows of floor-to-ceiling shelves that housed an estimated 45 million images. They praised his efforts to preserve priceless treasures of Americana that newspaper publishers were heedlessly shedding, and marveled at the rarities in his collection, including a trove of glass-plate negatives shot by pioneering baseball photographer Charles M. Conlon, and the encyclopedic George Brace baseball archive.

But the con artist straight from the pages of a novel by Little Rock’s own Charles Portis was running an elaborate Ponzi scheme atop a house of cardboard. He lied about the value of his collection to bilk investors out of tens of millions of dollars in loans, and created counterfeit memorabilia to serve as collateral for others. Even after he pleaded guilty to wire fraud, the incorrigible Rogers continued to peddle phony items and to swindle new victims.

“I have shit all over a once-amazing life,” Rogers posted on Facebook before he was imprisoned. “I have lost everything, including my freedom.” He blamed his ruinous disgrace on his three preferred vices: greed, hubris, and cocaine.

Those may well have been the only truths he told across the whole sordid affair.

Card Shark

Exactly when John Rogers began fleecing customers is unclear; he’s offered different accounts to different people, including law enforcement. What’s known is that he caught the collecting bug early.

He was born in Tupelo, Miss., in 1973, but grew up in North Little Rock, Ark., across the river from the capital city, in what locals call Dogtown. He bought packs of cards at The Scorecard, attended card shows up the road in Sherwood, and swapped and flipped cards with classmates and friends.

His boyhood hero was Dale Murphy, but as a card collector Rogers aimed higher. He set his sights on owning the Mona Lisa of cardboard, the T206 Honus Wagner card, released in 1909 by American Tobacco Company and valued for its scarcity: Some 50–75 authenticated Wagner cards are believed to exist. The young Eagle Scout supposedly had his parents, Ron and Mary John, drive him to the annual National Sports Collectors Convention—in Michigan or Texas, depending on the varying stories he later told reporters—just so he could glimpse the card, even then valued at $15,000.

“After that, I got a copy of it, cut it out and glued it to the back of a Nike shoe box,” Rogers told a reporter. “I eventually put it into my Van Halen wallet.”

Rogers soon discovered that selling cards was more fun and far more lucrative than his junior-high job of mowing lawns and his senior-high janitorial gig. He was a big kid—he topped out at 6-foot-6—and got used to haggling with adults from an early age. He was especially skilled at sniffing out people who could be persuaded to unload their collections. He told one reporter that he was always “selling and hustling, wheeling and dealing.”

“He was a wonderful talker, colorful, had great stories,” filmmaker David Hoffman told me. “Even though he was a giant guy, he always acted gentle and smart.”

“John was one of those people that could sell anything,” said Tim Rasmussen, former assistant managing editor for photography at the Denver Post. “He was a used-car salesman. He was inviting, funny, good at negotiations.”

“He was a gregarious deal-maker,” said former partner Doug Allen. “Just always positive, always everything was great.”

With his size, Rogers played offensive line for the North Little Rock High School Wildcats. (If the school sounds familiar, it made news recently after the Washington Post published photographs from 1957 showing future Cowboys owner Jerry Jones in a crowd attempting to block six black students from entering and desegregating the school.) He went on to play for Louisiana Tech University, where he continued to buy and sell cards to pay for his schooling. He graduated with a degree in marketing and business management in 1996 and returned home to Dogtown. Not long afterward, he opened a brick-and-mortar store called Sports Cards Plus in a shopping center.

Later, Rogers would tell conflicting stories about how he raised the funds to launch the business. In one interview, he claimed to have “liquidated real-estate holdings that I had and was able to self-finance the start with a $10 million investment.” Another version stated that “Grandma Turner loaned him the start-up money and office furniture.” A third account mentioned family money from a “chain of childcare facilities [that is] the largest childcare provider in the South” and “a GM dealership.” These were all tales from “the fabulist mind of John Rogers,” according to Arkansas Business reporter George Waldon, who wrote a groundbreaking series of articles that chronicled Rogers’s rise and fall.

Rogers married Angelica Luna, a Mexican-American woman whom he knew from before college and over whom he towered. She helped him with the business and earned income working in daycare. They relished their roles as the proud parents of three children.

Working 60-hour weeks, Rogers had a close-up vantage point as the sleepy, nerd-adjacent hobby of card collecting matured into a billion-dollar industry. Mom-and-pop shops in shabby strip malls gave way to auction houses, their glossy catalogs filled with lavish offerings, along with a nascent website called eBay. The launch of Beckett Baseball Card Monthly magazine in the early 1980s, along with early-nineties emergence of Professional Sports Authenticator (PSA) and its authentication and grading system, emphasized valuation and condition, and introduced fancy terms like “provenance.” Upstart card companies like Upper Deck elevated the stakes by challenging Topps’s longtime monopoly.

Cards and sports memorabilia morphed from hobbyist fascinations into speculative commodities, like fine wine and soybeans. Prices for the rarest items soared. Hockey superstar Wayne Gretzky and former Los Angeles Kings owner Bruce McNall made national headlines when they purchased a T206 Wagner card for a whopping $451,000 at a Sotheby’s auction in 1991. “McNall said through a spokesman that it was purchased for investment, not display,” the Washington Post reported, before adding, “In this sale, even the $30 catalog became an instant collector's item.”

Amid the boom-and-bust, oversaturated baseball card market of the late 1990s, Rogers bought and sold everything from vintage baseball jerseys and World Series rings to, reportedly, Elvis Presley’s jukebox and USC running back Charles White’s 1979 Heisman Trophy. He told one reporter that he made his first million at age 27.

His pursuit of rarities led him to what was then an untapped vein of collectibles: photography. In 2002, he reportedly paid $50,000 for the archives of Don Wingfield, a freelance photographer who shot for The Sporting News, Topps, and the Washington Senators, and who had used his pictures to produce postcard sets in the 1950s and 1960s. Rogers admittedly knew little about photography, but he appreciated the immediate profit, claiming that he flipped the Wingfield collection to Upper Deck for $350,000.

Now hooked on photos, Rogers bought the estate of esteemed photojournalist Arthur Rickerby (constituting 192,393 prints, slides, and negatives) for a reported $300,000, and in so doing moved beyond sports. Although Rickerby is renowned for his indelible image of Don Larsen throwing the final pitch of his 1956 World Series perfect game, he also shot the Civil Rights Movement and the assassination of President John F. Kennedy for Life magazine.

Others followed, including the archive of Barney Stein, the former team photographer for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Stein’s daughter, Bonnie Crosby, recalls meeting with John and Angelica at a fancy hotel in Manhattan to negotiate the deal, worth over $100,000. “He was charming and relaxed while he and his wife entertained us at lunch,” she told me. “They were showing off their wealth by being in this luxury hotel. The whole point of it was, he had an organization that would be able to make very fine prints and sell them.”

Photographer Andy Hayt, a veteran shooter at Sports Illustrated and numerous newspapers, recalls being introduced to memorabilia expert Frank Ceresi, who connected him to Rogers. Within a few weeks, Rogers struck a deal to purchase several thousand transparencies.

Hayt says he cashed a sizable check, but soured on the “transactional” nature of Rogers’s business. “Photography is a currency for them that has nothing to do with its value artistically,” he said. “They’re looking at the photos for their investment value. It’s about the price and what it’ll be worth 10 years from now.”

Rogers next snagged the archive of Sport magazine, a glossy monthly launched in 1946 under publisher Bernarr Macfadden that combined superb writing and photography (most notably, by freelancer Ozzie Sweet) until its demise in 2000. Rogers reportedly paid around $600,000 for the archive, and hired Chris Galbreath, a FedEx employee based in Memphis, to handle the logistics of retrieving, packing, and transporting 13 filing cabinets worth of pictures from Toronto to the U.S.

With approximately 2.2 million images in his archive, Rogers had built a presence in the undervalued and unappreciated niche of vintage sports photography. He was still a small-time operator in the heartland, known only to a group of passionate collectors, but that would quickly change.

In 2008, Rogers elbowed his way into national news when he landed the T206 Honus Wagner card he’d yearned for since childhood at an auction held at the ESPN Zone in Chicago. The price had soared in the intervening years. Rogers paid $1.62 million in a sale orchestrated by Mastro Auctions, after he “started drinking a bit and I think that gave me the extra courage,” he told CNBC’s Darren Rovell.

He threw a massive bash at his home so that friends and neighbors could gaze at the “Jumbo Wagner,” so nicknamed for its oversized borders. The “who’s who of North Little Rock” showed up, according to one former associate, including local politicians who arrived bearing gifts because they mistakenly thought that John and Angelica were celebrating the birth of a child named “Honus.”

“John got drunk that night and gave me the card to hang on to,” said a former employee. “I had it for two days until he called me about it.”

Rogers’s eagerness to embrace the spotlight caught the attention of Chicago-based FBI agent Brian Brusokas, who was part of a team investigating sports-memorabilia fraud. “Most collectors, when they purchase something of high value at auction, they usually stay anonymous,” Brusokas said. “What struck me as odd was that, right after purchasing that card, John went looking for media attention. He had a party at his home to show off the Wagner card, which is something most people don’t do.”

Mere months after the auction, Rogers offered the card on eBay for $2.5 million. It didn’t sell at that price, and he purportedly dumped it for a $600,000 loss in early 2009. Hobbyists posting on the collector forum Net54 were puzzled why Rogers had sold the card he had described as “the holy grail.”

“John was always a seat-of-his-pants kind of guy,” said former partner Doug Allen. “He’s the only person I know who ever took a loss on a Honus Wagner card. He turned around and sold it for a multi-hundred-thousand-dollar loss just because he wanted to move on to the next deal.”

Paper Trail

According to Rogers it was his friend George Michael, the veteran Washington, D.C.–based sportscaster, who suggested that he seek out the voluminous photography archives that newspapers across the country were summarily discarding. Michael himself was an avid photography collector and researcher until his death in 2009. (The namesake of the Society of Baseball Research award for “Pictorial History,” Michael’s personal photo pursuit was collecting pictures of baseball players sliding.) He'd spotted an opportunity.

With the economy cratering in the aftermath of the subprime mortgage crisis, and the internet wrecking the business model of print journalism, newspapers were hemorrhaging cash and looking to unload non-essential assets. That included the musty hoards of negatives and prints that photo editors had been stashing in metal filing cabinets and cardboard boxes, often unsorted and alphabetized, where they spent decades occupying precious space and producing zero income. At the same time, digital photography had rendered darkrooms largely superfluous; archive librarians were retiring or taking buyouts, and taking their institutional knowledge with them.

Rogers took Michael’s advice and found publishers “lining up to sell” their photo archives, as he put it, starting with the Detroit News for a reported $1 million. He offered what seemed like a sweetheart deal: Rogers’s company would cart away the negatives and prints, professionally scan them, return the archive to the newspaper in digital form complete with valuable metadata, and present them with a tidy check. In return, Rogers kept the physical copies—which he was free to flog on eBay or, if they were particularly rare, at auction, like a negative of Mickey Mantle in the nude that he reportedly sold for $25,000.

Sometimes the newspaper retained the all-important copyright; sometimes, depending on the contract terms, it fell to Rogers. That allowed him to monetize the archive via licensing agreements with sports leagues and television networks like ESPN and HBO.

Publishers saw Rogers as a godsend, delighted to have him handle the time-consuming and costly chore of digitizing millions of ancient negatives and yellowed prints, as well as the hassle and expense of storing them. Word spread quickly through the industry about this unique collector from Arkansas. He soon gobbled up the archives of other prominent newspapers, including the Denver Post, the Boston Herald, the Seattle Times, the Chicago Sun-Times, and the St. Petersburg Times.

“At a time when the decline in advertising was hurting us, the opportunity for an influx of capital in exchange for digitizing our photo archive made sense,” said Rasmussen, noting that Rogers paid $500,000 to digitize the Denver Post’s archive of approximately 2 million photographs. “A half-million dollars was a significant boost for us, and we were able to take these old images and bring them back into circulation.”

At climate-controlled facilities in North Little Rock and Memphis, a small army of archivists sorted and processed the photographs and negatives: cleaning each one, erasing edits, repairing tears, and scanning them, front and back, at a minimum resolution of 300 dots per inch. As the sheer volume of images swelled, Rogers outsourced processing work to India and Bangladesh, where workers added crucial metadata like the date, the subject, a brief description or caption, the photographer’s name, and the news service.

The resulting digital cache—organized, easily searchable, and stored on hard drives—went back to the newspaper, which now had the wherewithal to sell digital prints online. “We were bringing in a six-figure income every year from selling [pictures],” Rasmussen said. “We were splitting the proceeds with the photographers 50/50, so we had photographers who were there for 30 years who were getting checks.”

Dean Musgrove, photo editor of the Los Angeles Daily News, met Rogers when the latter flew out to L.A. “I didn’t think much of him,” Musgrove said. “He was disheveled and something about him bothered me. But we were going on what happened at our sister paper [the Denver Post]. It had worked out for them, so we felt OK doing that.”

Musgrove’s misgivings led him to deliberately hold back particularly prized photos from the O.J. Simpson trial and the L.A. Riots. “I said to myself, ‘Let’s see how this goes.’”

“[The newspapers] like the size of the checks we cut when we purchase the collections, the seven-figure checks, but what they like more is we provide millions in services,” Rogers told one reporter. In return, “we’re able to obtain priceless images. That’s what we do. To me as a collector, that’s my addiction. That’s our business model. It fuels our clients’ needs and wants. So it’s a win-win for everybody.”

By 2010, an article published in the Northwest Arkansas Democrat-Gazette estimated Rogers’s revenue was “$6 million to $8 million a year and is on track to top $10 million in 2010.”

But Rogers emphasized that his efforts went beyond mere revenue. His ultimate goal was to preserve “our nation’s history,” a stance that earned him publicity and praise.

“If America is one big family,” intoned CBS News anchor Scott Pelley before introducing a flattering segment about Rogers, “then we need someone to keep our family album. Fortunately, [John Rogers] is doing just that.”

Local papers hailed the “kid from Dogtown” and applauded his charitable side, including sizable contributions to the “Shop With a Cop Christmas Program” and funding scholarships for students who were the first in their family to attend college. Rogers joined his alma mater's “Team Tech 100,” alongside fellow alums Terry Bradshaw and Matt Stover, to support Louisiana Tech’s sports programs.

The worshipful coverage highlighted the soft side beneath his 300-pound frame and Van Dyke beard. “Because he’s such a big guy, people look at him like he’s kind of scary, but he truly feels for other people,” his wife Angelica told the Democrat-Gazette. “Once when he was just a teenager, we were eating at a Kentucky Fried Chicken. We had just sat down to eat when he got up and took his tray across the room. He came back a few minutes later without it.

“He gave away his food. He gave his dinner to a man who told him he hadn’t eaten all day. That’s all he said. He just loves people. He really does.”

The couple lived in a 12,449-square-foot castle that they built overlooking a lake on 5.5 acres of land in the Park Hill section of town, complete with a saltwater pool, grotto, indoor basketball court, batting cage, safe room, wine cellar, sauna, gym, and elevator. There, they hosted charity events like “Soiree at Snake Hill” to raise funds for programs at the high school.

Rogers’s archive grew to some 35 million images. With 300 or so people employed around the globe, he said that his company was processing about 400,000 photographs per month and about 50,000 negatives a day, a volume that, if true, set a mind-boggling pace.

“We’d like to buy every newspaper in the country, is our goal,” he said.

Glass-Plate Treasure

In June 2010, Rogers bought the photo archive of The Sporting News, a transaction valued at $1-2 million, according to differing published accounts. The "Bible of Baseball" had had two owners in its first 114 years of publication, but was now on its second new owner—American City Business Journals (ACBJ), a subsidiary of the Newhouse family's Advance Publications—in six years.

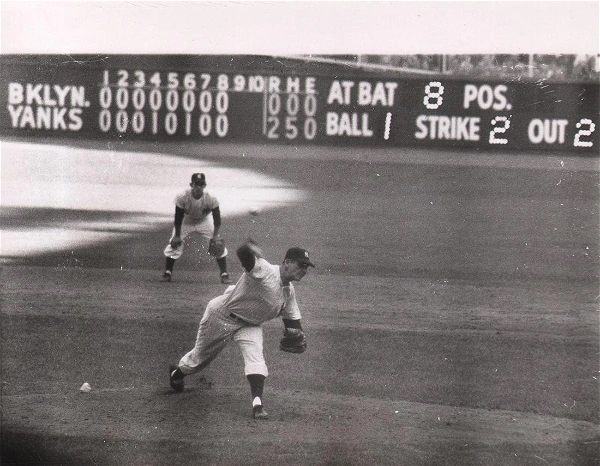

ACBJ bought The Sporting News in 2007 and moved the paper's operations from its longtime St. Louis home to Charlotte, N.C. The move included an archive of approximately 600,000 photo prints and negatives. The jewels of the collection were 8,354 original negatives shot by Charles Conlon.

A newspaper proofreader by trade, Conlon dabbled in landscape photography at the turn of the 20th century. But when the sports editor at the New York Evening Telegram encouraged him to venture out to the city’s ballparks, Conlon started lugging around a bulky Graflex View camera and stacks of 5x7 glass negatives to shoot the players, in action and in the dugout, for the Evening Telegram, the Spalding Base Ball Guide, The Sporting News, and Baseball Magazine.

Conlon documented the national pastime from 1904 to 1942, often without credit. His probing black-and-white portraits of Babe Ruth and Christy Mathewson toggle between documentary portraiture and fine art; his 1910 photo of Ty Cobb sliding fiercely into third ranks among the finest sports pictures ever produced. (The “Cobb Sliding” picture happens to be the only one of the surviving glass-plate negatives that was damaged.)

The Sporting News bought Conlon’s collection before his death in 1945. (Conlon himself destroyed thousands of negatives, claiming they were “running me out of the house.”) His name went virtually unrecognized for the next 45 years or so until the brother-sister duo of Neal and Constance McCabe curated a sumptuous coffee-table book that underscored his supreme artistry.

Rogers, the proud new owner of Conlon's life's work, likened Conlon to Civil War photographer Mathew Brady, and called him “the Ansel Adams of baseball imagery—he’s the biggest of the big in terms of early baseball images. … [To] own his original negatives is a dream come true.”

He told one reporter that, when he went to retrieve the collection, the irreplaceable glass negatives were buried under piles of junk in a closet. “They were down on the floor,” he told one reporter. “They were water-damaged, and on top of them were coats, phonebooks. … It was like an archeological dig.”

According to former partner Doug Allen, who traveled to Charlotte to inspect the Conlon collection, Rogers’s story is hyperbole. “Nope, they were all in archival boxes in a conference room, stacked neatly in alphabetical order, all sleeved. It was a beautiful thing to behold. John never did that. He makes his own truth, but that’s fine.”

Rogers boasted that curator-historian Frank Ceresi had appraised the Conlon cache at $8.4 million just months after the purchase. (He neglected to mention that Ceresi was also his occasional partner.) He moved swiftly to cash in on the investment, marketing a set of 11x14 Platinum-Palladium prints, featuring 150 images, with each individual print selling for $999.

If securing the Conlon collection was a grand-slam bargain, then acquiring the George Brace archive was hitting for the cycle. In 1929, photographer George Burke started shooting the Cubs at Wrigley and the White Sox at Comiskey, as well as the visiting teams passing through Chicago. Brace, his apprentice, inherited the job after Burke died; he paid for film and darkroom supplies by selling prints to fans, teams, and publications.

By the time Brace retired in 1994, he’d produced hundreds of thousands of negatives, depicting more than 10,000 players, and filling 57 double-layered drawers in large filing cabinets stored in the basement of his home. Photo editor Richard Cahan, who co-authored a coffee-table book about the archive, described it as “the nation’s finest private collection of baseball photographs.”

Brace died in 2002, leaving the archive to his family. Daughters Mary and Kathleen kept the business going, but with photography moving away from film, they found buying paper and darkroom supplies increasingly prohibitive. After Kathleen died, Mary and her niece, Deborah Miller, decided to digitize the collection. They bought an expensive scanner, but soon gave up. “We figured it would take us 15 years to finish it,” Mary told me.

Rogers had previously ordered prints from Mary. Sensing an opportunity, he swooped in and agreed to pay $1.35 million for the collection and the copyright, with an upfront payment of $500,000, to be followed by 10 annual payments. Rogers also promised to deliver a complete digital archive for the family’s use.

Of utmost importance to Mary Brace was preserving her father’s collection intact. “My dad spent his entire life forming this collection and I wanted to keep it together,” she said. “Rogers told me, ‘We’re gonna keep it together.’ He’s really smooth. He came along at the right time and made all kinds of promises. He told me just what I wanted to hear.”

Rogers immediately reneged on his word. He reportedly hawked dozens of rare photographs at auction without Mary’s knowledge.

“John had no patience,” a former employee at his archive told me. “When we would get an archive, he would immediately pull out the best stuff and sell them before we made [digital] copies of them. It was a nightmare working for him. He would make very public purchases and make very private sales.”

Rogers was an acquisition machine. He bought the archive of famed photographer Marvin Newman. He reportedly agreed to digitize the archives of 30 newspapers in the McClatchy chain and 20 newspapers of the Digital First Media group. He expanded into video by purchasing documentarian David Hoffman’s film archive. He obtained the complete library of The George Michael Sports Machine after his friend’s death, along with interviews from the old Gillette Cavalcade of Sports TV program.

In a 2012 interview with the Arkansas Times, Rogers said that his company would soon control more than 80 million images, with sales from eBay bringing in $120,000 a week. Another published report in 2014 estimated that the archive contained 220 million images. With a nod toward the national chain based in northwest Arkansas, Rogers claimed that his archive was becoming “The Walmart of Photography.”

His reputation had soared so high that he was no longer paying six or seven figures for newspapers’ photo archives; they were handing them over practically gratis, in exchange for his valuable digitization services. Rogers launched another company, Planet Giant, to sell murals and posters from the pictures in his control, and began building a portal that would enable him to sell them directly to consumers, including via auction, and to license images for TV, movies, and other ventures.

His self-assured mien and his student-of-American-history banter convinced others that his dealings were above-board, even as Rogers allegedly fudged the provenance of select memorabilia and purchased sketchy items from notorious collector Peter Nash, aka rapper Prime Minister Pete Nice of 3rd Bass.

“There was no reason to doubt John,” said Bob Failing, a memorabilia collector who later sued Rogers over an unpaid loan. “I met him and his wife and his kids. They were nice people. He put up a good front.”

Meanwhile, no journalist questioned his business model or how he was able to bankroll so many acquisitions. None examined whether his archive was honorably fulfilling the terms of each deal.

“John was like Getty [Images] on steroids—going aggressively after each and every archive,” FBI agent Brusokas said. “What he was saying was 100-percent right: These photos were an untapped and undervalued resource in the collectibles market. If done right, this could serve history well. But within a very short period of time, I was like, nope, it’s not going to be good. There was no way he could keep up with what he was promising people.”

“John was one of these people in life that have so many holes in their bucket that, regardless of how much water you pour into it, you can never fill that up,” a former partner said. “Enough was never enough. He was literally acquiring more stuff than he could process.”

Said another former employee: “John’s deal was always bigger, bigger, bigger.”

House of Cardboard

For Rogers, the chase was intoxicating. “With baseball cards, it’s bittersweet when you complete a set because the challenge was over,” he once said. “With photos, the challenge is never going to be over.”

But even as Rogers reportedly added 15,000 square feet of office space and hired additional workers, and even as he traveled abroad to make a deal to digitize the archives of the Fairfax Media newspaper chain in Australia and New Zealand, rumors that he was overextended and underfunded burbled in Arkansas banking circles.

Local lenders who’d done business with Rogers questioned how he was able to operate without a chief financial officer and how he could close deals despite a history of bounced checks, according to Arkansas Business reporter George Waldon. Others wondered how he could afford the mortgage on his lakefront McMansion and his New York City condo overlooking Central Park that he reportedly rented for $10,000 a month.

The collapse of Rogers's empire was gradual and then sudden, to paraphrase Ernest Hemingway’s line about going bankrupt. It can be traced to the dark side of the sports collectible industry, where incestuous ties between buyers and sellers, auction houses and appraisers, and well-heeled collectors and their insurance companies often crossed conflict-of-interest boundaries, creating a buyer-beware domain replete with counterfeit game jerseys, forged autographs, and bogus and stolen merch. One joke you’ll hear in these circles is that Mickey Mantle still signs autographs with an arm out of the grave.

Rampant fraud and forgery in the memorabilia market had caught the FBI's attention by the mid-1990s. Findings from the agency's first crackdown, Operation Foul Ball, which estimated that “forged memorabilia comprises over $100 million of the market each year,” led to Operation Bullpen, an undercover campaign to "infiltrate the nationwide memorabilia fraud network." In 2008, the agency took down one of its prime targets: Burr Ridge Ill.–based Mastro Auctions, the leading sports memorabilia auction house.

On the very same day that Mastro sold the holy-grail T206 Honus Wagner card to John Rogers for $1.62 million, agents swarmed the auction house's booth at The National, a memorabilia convention in Chicago, and handed out federal grand jury subpoenas.

Mastro Auctions was shut down the next year amid allegations of selling “phony and altered memorabilia,” according to the U.S. Attorney’s Office, including the T206 Wagner card purchased by Gretzky and McNall in 1991. CEO Bill Mastro later admitted to trimming the card's side borders with a paper cutter to improve its appearance and value. (Arizona Diamondbacks owner Ken Kendrick now owns the card.) Federal investigators also concluded that Mastro rigged auctions through “shill bidding,” a shady practice that inflated the prices that buyers paid. Among the victims were Keith Olbermann, Penny Marshall, and Hal Steinbrenner.

With their CEO under indictment, several Mastro Auctions executives, including Doug Allen, left to form Legendary Auctions. Among the silent investors funding the new company was John Rogers.

Rogers supplied Legendary Auctions with vintage photographs from his archive, including from the Brace collection—the one he'd promised to keep intact. Allen, who helped Rogers finance the purchase of the Conlon collection and partnered with him on several projects, took possession of what he described as “100 or so of the most iconic images. I took ‘Cobb Sliding,’ I took all the Ruths and the Mathewsons. I stored those in my safe.”

On a hobbyist message board, Rogers repeatedly called Allen “a great guy.” But at that point, Rogers did not know that Allen, who was being investigated for fraud at Mastro, had agreed to wear a wire to ensnare other targets of the FBI probe, including Rogers himself.

The case took an unexpected twist when Allen admitted to Rogers that he was cooperating with the feds. What Allen didn’t know, when Rogers baited him into confessing that he was wearing a wire, was that Rogers too was secretly recording their conversation. As a result, Allen lost his chance at a reduced sentence and went to prison for 57 months.

“That was the worst day of my life,” Allen said, “walking in and them playing the recording he had of me. Wow. I tried to help this guy, and I had to go and tell my wife that day that, you know what, what I thought was going to be better for me is going to be worse for me now.”

“Doug did something unforgivable to me,” Rogers later said in an in-prison interview with the American Greed TV show. “You don’t want to rat. People like that, they ought to be shot, I think. But I took an exception for Doug Allen. I said, you know what, this scumbag deserves to pay for this. I wired up against Doug. I made sure that son of a bitch got his sentence doubled. And I don’t regret it. And anybody that has a problem with it and wants to call me a rat can kiss my ass.”

Allen had also warned Rogers that the FBI was planning to execute a search warrant at his home and businesses in North Little Rock. Brusokas was at home one evening in January of 2014 when he received a phone call from an Arkansas number. He was shocked to hear John Rogers on the line, speaking in a booming voice.

“‘Brian, it’s John Rogers here,’” Brusokas recently recounted from memory. “‘Doug is playing double agent. I don’t want to be involved in this. We’re at a restaurant right now. He went to the bathroom. I got your number out of his phone. I know you’re doing a search warrant at my house. Please don’t hurt my dogs, don’t hurt my family. I’m gonna cooperate. I gotta go.’ Click. He hung up.”

Jan. 28, 2014 was a blisteringly cold day in North Little Rock. Brusokas had driven from Chicago through a winter ice storm to lead the FBI raid on Rogers’s home and three business locations. Thanks to Allen’s tip, Rogers was “prepared” for the search warrant, according to government prosecutors.

“After we did our security sweep,” Brusokas said, “John was sitting on his couch and he had a big smile on his face. He said, ‘See, I told you I knew you were coming.’”

Even so, what the FBI seized showed Rogers's skill in the sinister practices of the trade, right down to the accoutrements of forging authenticity: vintage typewriters, phony hologram stickers, fake photographers’ stamps. He had also filled the pages of a notebook with practiced signatures of everyone from Babe Ruth to Ronald Reagan to Frank Sinatra.

John being John, he couldn’t resist ribbing Brusokas. Inside the notebook, written in the penmanship of Babe Ruth, was this message: “To my pal Brian. The finest FBI agent.”

Another challenge was that Rogers had mixed the good with the bad: a vintage photo of Mickey Mantle, say, but with a bogus autograph; a bat actually signed by Dale Murphy, but with four fake signatures of other Braves stars. To really confuse matters, a ton of stuff was 100-percent genuine.

According to Brusokas, Rogers was particularly adept at concocting memorabilia related to his home state. Like many ballplayers of yore, Babe Ruth came to Hot Springs, Ark., for spring training (and gambling, golf, and the hot springs). Rogers acquired an antique steamer trunk and tried to pass it off as Ruth’s personal luggage.

Rogers fabricated memorabilia related to Chicago Bulls star Scottie Pippen, an Arkansas native who played ball at the University of Central Arkansas. Rogers allegedly sold several All-Star Game participation trophies given to Pippen; the NBA does not hand out All-Star Game participation trophies.

The FBI interviewed associates and employees at Rogers’s archive and conducted a forensic accounting of his financial records. Their investigation unleashed a trickle and then a tsunami of lawsuits that exposed the scams, unpaid loans, and fraudulent collateral that Rogers used to bamboozle investors and partners.

An opening salvo came from Mark Roberts, a wealthy collector who, with assistance from curator Frank Ceresi, had launched an online museum dedicated to the history of the national pastime. According to Roberts’s lawsuit, filed in February 2014, the nearly 3,000 vintage photographs he had purchased from Rogers for more than two million dollars were copies worth only a fraction of what he'd paid.

Next came Mary Brace. She’d received the initial $500,000 payment from Rogers for her father’s photo archive. She was supposed to receive $85,000 annually over the next decade, but the payments stopped after one year. Rogers also failed to provide her with a complete digital copy of the Brace collection, as he had promised. “I was supposed to retire with the money,” she said. “That’s why I made the deal for 10 years, so I would have something to live on. That never came about.”

As for the scans? “He gave me a little thing that had a couple hundred random photos on it,” she said. “That was a joke.”

Rogers’s personal life was upended in August, when his wife sued for divorce, ending their 18-year marriage. Angelica Rogers reportedly received full ownership of Sports Cards Plus and the photo archive business, the couple’s home and other properties, a 2012 Mercedes, and custody of the three children, ages 16, 14, and 12. (What Arkansas Business described as “the house that fraud built” later sold for nearly $1.3 million out of foreclosure.)

Angelica informed her ex-husband’s clients that she was now running the business. That arrangement drew a mixed response. “Skeptics view the divorce as a move to protect assets from creditors,” Waldon wrote.

Rogers’s attorney Brett Myers (and the other lawyers who succeeded him) needed a scorecard to keep track of the filings inside the historic Pulaski County Courthouse in downtown Little Rock. The First Arkansas Bank & Trust led the parade of plaintiffs, filing lawsuits over four delinquent loans, personally guaranteed by Rogers, totaling $14.5 million.

In one case, the bank loaned Rogers $3.5 million to purchase a cache of rare baseball card sets, which Rogers valued at $15 million, from noted collector and merchant Larry Fritsch (widely considered to be the first person to sell baseball cards full-time, back in 1970 in Wisconsin). When the FBI confiscated the cards and had them analyzed, they were deemed counterfeit.

The bank also loaned Rogers $1.5 million to purchase David Hoffman’s video archive, only to discover later that the price Rogers actually paid was $325,000. Hoffman himself filed suit in November for $80,000 that Rogers owed him.

Even while losing operational control of his companies, Rogers kept blustering. He told a reporter that he had just “closed a deal to buy about 15 million negatives” from several southern California newspapers. “I’m taking this opportunity because I feel I have a duty [to save the photos],” he said.

“We took on too much digitization work,” he admitted. “The cost outweighed [the revenue]. We are adjusting to that now. We’re creating new revenue streams and I believe fully we’ll pull out of this.

“I’m learning from my mistakes,” he continued. “I’ve got every faith in the world that we can work this out.”

His tangled lies further unraveled when business partner William “Mac” Hogan and Arkansas backer John Connor Jr. filed separate lawsuits over unpaid loans. “I thought that what he was trying to do was the correct thing, and I found out it wasn’t,” said Connor, a rice and soybean farmer who sued Rogers for $9.6 million. “I don't think he was representing the correct facts to the people that were working with him, and consequently things didn’t work out very well.”

Hogan detailed a series of “phantom transactions” that Rogers fabricated as part of a Ponzi scheme to borrow money from one entity to pay off the loans of another. Among them: Hogan allegedly lent Rogers $2 million to purchase the photo archive of The Oklahoman newspaper in exchange for 50 percent ownership. But The Oklahoman had been one of the few publications that turned down Rogers’s entreaties to buy and digitize their photos. Instead, Rogers crafted a “bogus sales contract with the Oklahoma City newspaper,” according to Arkansas Business, to show Hogan.

Hogan also lent Rogers $150,000 for a 50 percent stake in the $300,000 purchase of Billy Sims’s Heisman Trophy, awarded to the University of Oklahoma star running back in 1978. But this version was a doctored creation, according to the FBI. Rogers bought an honorary trophy given to radio broadcaster Al Helfer, the longtime “Voice of the Heisman,” for approximately $50,000, affixed a Billy Sims nameplate that he had made at a local shop, and typed up a sham “letter of authenticity” with a forged Sims signature.

In total, Hogan sought $12.3 million, plus $39 million in punitive damages. “To say we were hoodwinked would be an understatement,” Hogan admitted, according to Waldon.

Brothers George and Steve Demos sued Rogers after he promised them $3 million, plus a 50 percent share of the Minneapolis Star Tribune’s archive, in exchange for a legitimate game-used bat that Babe Ruth hit a home run with during the 1924 season. After Rogers failed to deliver the money, he promised that he would hold onto the bat until he could pay them. Instead, desperate for cash, Rogers sold the bat for far less than market value.

Photographer Marvin Newman came next. He sued for breach of contract when Rogers allegedly didn’t pay him the agreed-upon sum of $400,000 and returned substandard digital scans of his pictures.

These and other claims against Rogers exceeded $45 million, not counting tens of millions more in punitive damages, according to Arkansas Business. As the volume of claims climbed, Pulaski County Circuit Court judge Chris Piazza appointed Little Rock business consultant Michael McAfee as receiver to preserve the photo collections, manage Rogers’s holdings, liquidate the assets, and distribute funds to the various creditors.

McAfee’s first challenge was to decipher Rogers’s flimflam dealings. McAfee told one reporter that “he had been approached by someone who claimed he had been promised—with a note written on a bar napkin—a percentage of Rogers’s company.”

“Here’s the case number,” McAfee told the man. “Please feel free to file a claim.”

McAfee found that Rogers had “overpledged” ownership stakes in the Conlon collection, his prized possession, to multiple individuals and creditors, resulting in well over 100 percent ownership. On top of that, each transaction assessed the collection at a differing amount. One investor “paid Rogers $1.1 million for a 25 percent interest,” according to Waldon, while another paid $350,000 for a 25 percent share and 125 original negatives. McAfee also discovered that hundreds of Conlon’s negatives had “evaporated” from Rogers’s warehouse. They were presumed lost, stolen, or sold.

Rogers’s unrelenting meddling vexed McAfee. According to published reports, Rogers entered negotiations with Atlanta-based Red Alert Media Matrix and its CEO Timothy Holly to buy the entirety of the receivership’s assets (except for the Conlon collection). Red Alert made an all-cash bid of $59 million, but “couldn’t provide verified funds to satisfy [McAfee],” according to Waldon. Red Alert next offered $28 million cash and a million shares of company stock valued at a whopping $972 million, and after that was rejected, unveiled a third proposal of $18 million and a billion shares of stock. The court rejected the three overtures, in part because of Rogers’s involvement.

Then, shortly before midnight on a Saturday evening in August 2015, Rogers defied a court order to stay away from his former business at 115 E. 24th Street in North Little Rock. He was accused of swiping three five-terabyte hard drives with over one million scans of photographs, including the metadata, that he claimed to own.

In December, Rogers was nabbed on burglary charges for that incident. It was his second arrest that year, following contempt of court charges in July.

He later stated that he was high on cocaine and grappling with his addiction. “I made hugely regretful, shameful mistakes, clouded in the daily haze of drug addiction,” Rogers posted on Facebook.

-30-

On October 7, 2016, just days after the “Jumbo Wagner” tobacco card that Rogers had once owned was sold for a record $3.1 million at auction, he appeared for his arraignment in U.S. District Court in Chicago. He was charged with one count of felony wire fraud to obtain at least $10 million from banks, partners, and clients.

According to federal prosecutors, Rogers “falsely represented that he had secured contracts to purchase certain collections of sports memorabilia and photograph archives, and found buyers to purchase these collections and archives at a profit, when he knew these statements were false because the deals did not exist and because he created contracts that he showed to investors.”

His motive for years of lies, scams, and grifts? “Greed,” he said.

Rogers initially pleaded not guilty, but changed his plea to guilty in March 2017. But, facing a reduced prison term because he had been cooperating with federal authorities in other investigations, Rogers wouldn’t or couldn’t quit. While freed on bond as he awaited sentencing, Rogers allegedly persisted in producing and selling fraudulent memorabilia, using various aliases and the assistance of a new girlfriend to camouflage the schemes and con victims, according to federal investigators.

On Nov. 20, 2017, Rogers appeared inside the Dirksen U.S. Courthouse in the Chicago Loop. Brusokas took the witness stand and testified for several hours about Rogers’s latest efforts to sell counterfeit items, including a fake commemorative football from the first Super Bowl. Judge Thomas Durkin had heard enough. He revoked Rogers’s bond and ordered him held at Chicago’s Metropolitan Correctional Center until sentencing.

One month later, Rogers returned to court for sentencing. His youngest son wept after Rogers admitted that he was no hero. “I didn’t think of [you] when I was doing those things,” he said.

Because he had violated the cooperation deal with the feds, his projected eight-year prison term was boosted to nearly 12 years. Now 50, Rogers is currently jailed at the federal correctional institution in Forrest City, Ark., located some 90 miles east of North Little Rock.

In 2020, he filed a motion for compassionate release, citing underlying health conditions (obesity and asthma) that made him vulnerable to serious complications if he contracted COVID-19. Judge Durkin denied the motion, writing that reducing his sentence would “disrespect the seriousness of his crime and principles of justice,” and that Rogers has “already demonstrated a propensity to commit crimes even when he is under close scrutiny by law enforcement.”

His current projected release date is Feb. 16, 2027, to be followed by three years of supervision.

Written interview requests sent to Rogers were not answered. Interview requests made to his father’s email address were ignored. Angelica Rogers, who currently works as a real estate agent in Arkansas, declined to speak with me.

Those who know John Rogers best don’t believe he’s completely abandoned the business, even while he sits in prison. They point to the website of an outfit called Regal Photo Archive that is seemingly acting as a front for the Rogers Photo Archive, complete with matching “RPA” initials and lens-shaped logos. Regal’s copyright was recently extended to 2023. The list of the newspaper, photographer, and video collections Regal claims to have “restored and digitized” matches exactly those that Rogers once controlled, including those of the Denver Post, Sporting News, Sport, Charles Conlon, and George Michael.

A recent legal listing describes Regal as a subsidiary of the El Dorado Family Group, as is Red Alert Media Matrix, the company that unsuccessfully attempted to purchase Rogers’s entire archive out of receivership. El Dorado CEO Timothy Holly is also the president of Red Alert Media Matrix. Numerous attempts to contact Holly through El Dorado and its affiliates were unsuccessful.

The fates of the photo archives that Rogers owned or controlled are mixed. By violating signed contracts and cannibalizing the very archives he claimed to be preserving, Rogers destroyed the essential integrity and comprehensiveness of collections that visually detailed the story of one city, one sport, one team, one photographer’s life work. As one law-enforcement officer put it, Rogers “raped and pillaged archives and destroyed history.”

“We would cut corners to turn around and digitize a newspaper archive [in six months],” said one of Rogers’s former employees, “because John was in such a hurry. We promised them that we’d scan the images at a certain dpi. We fudged that and scanned them at 200 dpi and then converted it to 600 dpi. The quality wasn’t there. The newspapers got burned badly.”

Dean Musgrove of the L.A. Daily News recalled that when Rogers sent him back the hard drives, “I’d open them up and there would be this long string of numbers,” he said. The scans were “almost useless” because “nothing was captioned. It was terrible.

“I tell people, ‘Our archive was stolen from us,’” Musgrove continued. “Every week, every month, I face this problem, like when [former L.A. Mayor] Dick Riordan passed away [in April 2023]. We had tons of staff photos of Riordan taken over the years, but they don’t exist because they were in the print archive that went to Rogers. We had to pull photos from AP and Getty.”

Multiple attempts to contact Michael McAfee were unsuccessful. Neither a comprehensive inventory of the collections of Rogers Photo Archive nor a record of how the receiver dispersed them has ever been released to the public.

Some publishers, like the Fairfax Group in Australia, lost an untold number of photographs. Tim Rasmussen, formerly with the Denver Post, experienced regret and guilt for recommending Rogers’s services to other newspapers.

“For us [at the Post], it was a very good arrangement working with John,” he said, noting that their contract had rigorous guardrails. “But then I helped John make deals for a lot of other newspapers, and he screwed them over royally and they lost their archives and got nothing for it. … I felt like crap because I had vouched for the guy and for the process.”

Memphis-based Historic Images, run by Chris Galbreath, a former partner of Rogers, bought part of the diminished archive from the receivership for an undisclosed amount. The company has essentially followed Rogers’s original business model: offering original prints on eBay and through its website, which boasts “a catalog of nearly 30 million images.”

Historic Images eventually sold the remains of the Chicago Sun-Times archive to collector Leo Bauby, who then sold the negatives (further reduced in number) to the Chicago History Museum in 2018 for $125,000. The museum is actively digitizing the archive.

Mary Brace won a $780,000 default judgment against Rogers, but the remains of her father’s collection were sold to Chicago-based Digital Archive Group, led by archivist Jeffrey Kelch, for a reported $46,500. “I acquired the [Brace] collection legally from the court,” Kelch told me. “I asked a lot of questions because my intent was to save the collection so that it didn’t end up the way [Rogers] was doing, which was trying to break it apart and sell it to collectors. I bought it to keep it out of the hands of collectors who were going to bastardize the thing and sell it over and over and over.”

“Mary Brace got hosed,” insisted one of Rogers’s former partners. “That was her father’s life work and that was her retirement. That collection can never be recreated.”

Photographer Marvin Newman prevailed in his lawsuit and recovered his photographs. “I’ve been in the business a long time,” said Newman, now 95 years old. “I never ran into someone like Rogers. I thought I was dealing with a regular businessman. The guy’s a thief.”

In 2016, the 7,462 recovered Charles Conlon negatives were sold at auction to an anonymous buyer for $1.8 million. The whereabouts of the collection remain a mystery; Dallas-based Heritage Auctions declined my written request to connect me with the buyer, purported to be a wealthy private collector in the southwest.

“It’s weird because [the buyer] has done nothing with it,” said Doug Allen. “They didn’t donate it to the Hall of Fame and take a tax write-off. To my knowledge, they haven’t tried to monetize it. Nothing’s happened with them.” (For the record, the Baseball Hall of Fame in upstate New York has original Conlon photographs in its archive, created from the negatives by Conlon himself, but not the negatives themselves.)

Many people who worked with or for Rogers declined to speak with me on the record. This was particularly true among those living in Arkansas.

“John is a fantastically awesome guy, but his alter ego is the biggest asshole in the world who lies to everybody,” one former partner said. “He’s literally a Dr. Jekyll/Mr. Hyde.”

In tracing the deals they’d done together over the years, “everything [John] had told me up to that point was a lie,” this partner realized. “To the best of my ability, I’ve tried to put this in my rearview mirror and break the mirror off.”

The mother of another former employee refused to let me speak to her son on the phone. “He went through hell,” she said. “Broke my heart.”

Another former partner told me that he has “zero comments or interest [in] revisiting anything that caused agony, pain, and anguish.”

Others bemoaned the lost opportunity. If Rogers had committed to patiently scaling the archive business, they said, he could have succeeded without having to resort to dirty tricks. “Done properly, we could’ve done something that we would be proud of,” a former employee said. “Preserving all this wonderful art and making money at the same time—everybody wins.”

“He had a legitimate archival business,” said one person who did business with Rogers, “but I guess there wasn’t enough action. Just making money was not what it’s about [for him]. It’s about the action. It’s about the danger.”

Those looking for a sliver of a silver lining to this story could spot it on baseball fields in Little Rock and Chicago’s South Side. There, not long after Rogers was imprisoned, teenagers took to the diamond using hundreds of wooden bats and baseballs that Rogers had desecrated with fake autographs. The FBI had seized the equipment during its investigation. After rubbing off the forged signatures, the FBI gave the gear to local youth baseball leagues.

Suggested Reading:

Baseball’s Golden Age: The Photographs of Charles M. Conlon, by Neal McCabe and Constance McCabe. New York: Abrams, 1993.

The Big Show: Charles M. Conlon’s Golden Age Baseball Photographs, by Neal McCabe and Constance McCabe. New York: Abrams, 2011.

The Card: Collectors, Con Men, and the True Story of History’s Most Desired Baseball Card, by Michael O’Keeffe and Teri Thompson. New York: William Morrow, 2007.

Card Sharks: How Upper Deck Turned a Child’s Hobby into a High-Stakes, Billion-Dollar Business, by Pete Williams. New York: Macmillan, 1995.

Cardboard Gods: An All-American Tale Told Through Baseball Cards, by Josh Wilker. New York: Seven Footer Press, 2010.

The Game That Was: The George Brace Baseball Photo Collection, by Richard Cahan and Mark Jacob. Chicago: Contemporary Books, 1996.

The Great American Baseball Card Flipping, Trading and Bubble Gum Book, by Brendan C. Boyd and Fred Harris. Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1973.

Mint Condition: How Baseball Cards Became an American Obsession, by Dave Jamieson. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2010.

Operation Bullpen: The Inside Story of the Biggest Forgery Scam in American History, by Kevin Nelson. Benicia, CA: Southampton Books, 2006.

A Portrait of Baseball Photography: The Definitive History of Our Pastime’s Pictures, News Services, and Photographers, by Marshall Fogel, Khyber Oser, and Henry Yee. Willowbrook, IL: MastroNet, 2005.

Through a Blue Lens: The Brooklyn Dodgers Photographs of Barney Stein, 1937-1957, by Dennis D’Agostino & Bonnie Crosby. Chicago: Triumph Books, 2007.