Sports Illustrated's final, unequivocal coins-on-the-eyes/book-the-caterer-and-rent-the-hall/sell-the-clothes-and-the-furniture demise is not yet officially here, but it's closer than ever before with the news that possibly everyone still working there had been given a time-released pink slip. The once-proud bible of sports journalism, which has been dying for two decades, will now be turned into either a checkout stand staple with breaking news like "The Celtics Dynasty Of The '60s" or "The 1984 Summer Olympics: A Retrospective," or just an empty space to be taken up by either "Quilting Quarterly" or bags of Chex Mix.

The nuts and bolts are these: Authentic Brands, which held SI's fate in its hands, noticed it hadn't been paid the latest installment for the use of the license by the Arena Group that ran SI, and decided to cancel the license and can everybody still working there—even the good ones. According to the email announcing that ABG was done with journalism, there was a glimmer of hope in that some of the employees had been told they would be kept on longer while the company looks for someone else to take up the banner. But if nobody comes forward, SI will become just another line-item death amidst all the others in the journalism field. And with it, all the emotional reactions coming from people well into their 50s and therefore not members of the demographic in which American business believes its future resides.

In truth, though, SI has been dying for years—though through no fault of the many excellent journalists who worked there, who produced worthy work right up until the end, probably to the dismay of the corporate pterodactyls who swooped over them. The slow death also goes back well before Time Inc., which created SI seven decades ago, sold it off for cash to pay the estate taxes. The SI brand was supposed to have value beyond the swimsuit issue, but it didn't, and neither does the swimsuit issue for that matter. It's all attic filler now, waiting for some garage-sale zombie to buy old issues and take them home until their own garage sales come to claim them. The SI the nostalgics remember ended well before the turn of the century, when print turned to electronics and access to the special stories and their protagonists was resisted rather than welcomed.

Oh, there was still writing and writers, photos and photographers. There were stories that could be told nowhere else, and people of quality who could tell them. There was inspiration and entertainment to be had one day out of every week, for as long as one day a week was sufficient response to the curious. Then again, as we have all learned, immediacy cannot abide turnaround time, and the well-crafted tale you knew nothing about has slowly but surely been replaced by in-game betting in your own home, which isn't clever or nuanced or thought-provoking or even helpful but is immediate as hell.

In addition, SI's once-envied monopoly of access eroded as sports leagues, agents, and athletes all learned that access implied the need for middlemen like journalists, and middlemen aren't an efficient use of the resource. There was no longer the prototypical Pat Putnam boxing story, in which he would get access to Muhammad Ali in his hotel room hours after the fight—access nobody could get because nobody could rival SI for prestige.

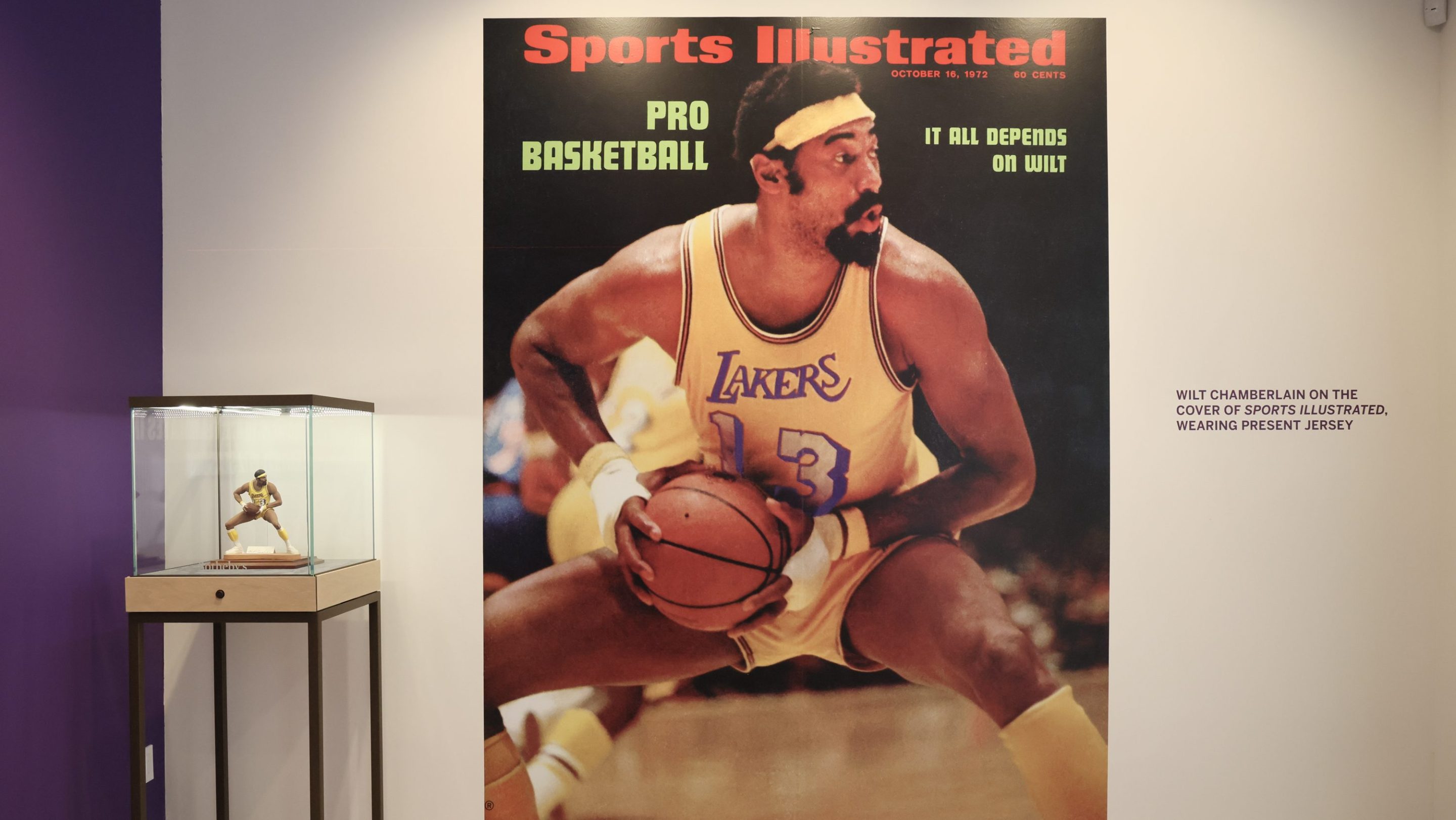

The most glorious glory days of SI were indeed the '60s and '70s, which we needn't remind you is half a century ago, and the introduction of the annual swimsuit issue was, in fact, the magazine's first true heel turn against its roots because it was the first acknowledgement that, even in the '60s, the stories weren't working with the same economic efficacy—that the exclusive access stopped being exclusive and eventually stopped being access at all. SI writers still got good seats to events, but they had to work with the interview rooms the proles did and the very occasional and rarely insightful walk to the bus before even that avenue closed.

More than that, though, there were a million incidents like this: Two of my daughter's high school classmates were staying over our house one Saturday night in the early aughts, and come Sunday morning they were both offered a chance to read the Sunday sports section because that's where their mid-teens curiosities began and ended. They both declined, and one of the two, now in his early 30s, said with an unsettling level of pride, "Oh, nobody reads the paper anymore." And the other joined in with an even more self-pleasing, "Nobody reads anything any more. It'll be on TV if it's important."

That conversation right there, and the millions just like it, were the end of SI—a slow-motion demise that came a few un-renewed subscriptions at a time. Again, at the risk of repetition, there was still good work to be found all the way to the last few months, as there is in newspapers, but the money got in the way of the art, and then the steady erosion of customers got in the way of the money. The license issue was just the excuse; nobody was getting paid any more, and the evolutionary result was that nobody would get paid ever again.

Sports Illustrated didn't die Friday, not the SI that will be rhapsodized about all weekend. It has been dead for a very long time. The amazing thing, if you think about it, is that it couldn't last even as long as newspapers, the thing that it was created to augment and improve upon seven decades ago, and whose episodic but inevitable death had been predicted well before SI's. Newspapers, indeed, are the most stubborn of the media survivors because of the army of septuagenarians who still want the tactile feel of the news, even though it isn't news at all any more but stuff that happened before lunchtime the day before.

SI failed to maintain its hold on America's few remaining coffee tables, and Friday's dagger was not only another punch to the windpipe of journalism but another admission that corporate America hasn't the wit or interest to sell journalism on its own merit, printed, videographed or digitized—merit as the information and thought conduit that could help us all achieve what prior generations thought this country was supposed to hold dear. Now, it's all just a race to beat a reaper that is picking up size, speed, and weaponry—a video game in which the best any of us can hope for is to read the screen that says "Level Two."