The press conference to introduce Chauncey Billups as the new head coach of the Portland Trail Blazers began like any other. There, at one end of the table was was Billups, clad in a dark grey suit, white button-down shirt, and dark red tie, the official colors of the team. And next to him sat the general manager, Neil Olshey, in a light grey suit that matched his full head of grey hair. They both wore lapel pins made with the Blazers' signature logo. Every detail was impeccable and well coordinated, right down to the prepared answers to questions about that time in the late 1990s, when Billups, then in his rookie season with the Boston Celtics, was sued by a woman who said he sexually assaulted her. The case also was investigated by law enforcement, with no criminal charges filed.

Olshey spoke first, saying he wanted to address the "some of the feedback" that had come up.

"With all sincerity, and you have my word along with everyone else in the organization, we are aware of the concerns that have been expressed by people regarding some serious allegations Chauncey faced in 1997. We took the allegations very seriously, and we treated them with the gravity that they deserve," he said. "Even though other NBA organizations, business partners, television networks, regional networks, have all enthusiastically in the past and present offered Chauncey high-profile positions with their organizations, we wanted to make sure we had our own thorough process because some things are just bigger than basketball."

Olshey said the organization did a traditional background check and commissioned an outside investigation that "corroborated Chauncey's recollection of the events that nothing non-consensual happened."

"We stand by Chauncey, everyone in the organization," Olsey said, "and we believe he's the right choice to be our head coach and the right choice to be the kind of ambassador in the Portland community everybody here has become accustomed to."

Without missing a beat, Billups spoke next. He, too, had prepared remarks.

"There's not a day that goes by that I don't think about how every decision that we make can have a profound impact on a person's life," Billups said. "I learned at a very young age as a player, not only a player but a young man, a young adult, that every decision, you know, every decision has consequences. And that's led to some really, really healthy but tough conversations that I've had to have with my wife, who was my girlfriend at the time in 1997, and my daughters about what actually happened and about what they may have to read about me in the news and in the media.

"But this experience has shaped my life in so many different ways. My decision making, obviously. Who I allow to be in my life. The friendships and the relationships that I have and how I go about them. It's impacted every decision that I make. You know, it really has. And it shaped me in some unbelievable ways. So I know how important it is, you know, really, to have the right support system around you in particular during tough, difficult times. And it's something that I've tried to instill in all of the players that I've played with over the course of my career, just sharing some of my experiences and things and maybe it will help them, you know, down the road at some point."

Billups closed his prepared remarks by saying this was his dream job and this day was "one of the best days of my life."

The rest of the press conference would not go as smoothly as those well-timed, perfectly coordinated remarks, most notably when reporter Jason Quick with The Athletic asked Billups to further explain his comments about how what happened in 1997 had shaped him. It was at this point that a member of the Blazers' staff, off camera but audible in the video, said, "Jason, we appreciate your question. We've addressed this. It's been asked and answered, so happy to move on to the next question here." At the same press conference, Olshey told reporter Sean Highkin of Bleacher Report, who asked for more details on the independent investigation, "That's proprietary, Sean, so you're just gonna have to take our word that we hired an experienced firm that ran an investigation that gave us the results we've already discussed."

But the public records regarding what happened in 1997 are, it turns out, not proprietary. The woman—who said she was sexually assaulted by Billups, his then-teammate Ron Mercer, and another man named Michael Irvin (not the former football player) at the home of another then-Celtics player, Antoine Walker—spoke to police and filed a lawsuit in civil court. More than 200 documents filed in the woman's civil lawsuit are open to public inspection. Defector Media obtained a copy of the file. Over the course of more than 1,400 pages, it lays out in great detail what the woman, using the pseudonym Jane Doe, said happened to her that night, as well as how Billups, Mercer, Irvin, and Walker all defended themselves from her lawsuit. Their defense consisted of challenging the constitutionality of the law she filed under and, when that didn't work, insisting all the sex with all the men was consensual and that Doe was just trying to blackmail the famous men into giving her money so that she wouldn't ruin their endorsement deals.

Defector Media reached out to the Blazers's media contacts for comment, but they did not respond. Defector Media also attempted to reach Walker, Mercer, and Irvin for comment but received no replies.

Doe said the assault happened on either late Nov. 9 or in the early hours of Nov. 10, 1997. That year was Billups's rookie season, after he was chosen third overall in the NBA Draft by the Celtics. From the moment the investigation began, authorities said very little publicly about what was happening. The Boston Herald reported on Dec. 4 that Waltham police and the Middlesex County District Attorney's Office were investigating a report of sexual assault at Walker's home.

"Sources indicated to the Herald that Walker is not accused of the alleged assault," said the Herald report, "but may have been with one or more men when they picked up the woman at a bar about a month ago."

There is no mention of Billups. Mercer's name does appear in the Herald report because he's mentioned as one of Walker's neighbors. There were no other news reports on the investigation or what happened, at least that I could find, until Doe filed her lawsuit in federal court the following April—but the article in the Herald on that lawsuit, which was published in May, doesn't say much because Doe filed her complaint under seal. This appears to be part of why what happened that night seems so shrouded in mystery.

But Doe's complaint is now unsealed. She filed one complaint and would later amend it to add more details. One version of the amended complaint, the second one she filed, remains under seal. But the third one, which was accepted by the court, is public. Here is what she said happened that night, based on the final version of her complaint which she filed with the court.

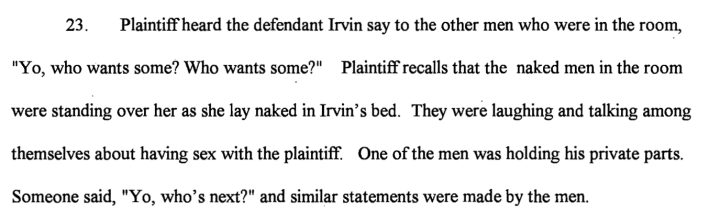

Doe said in her lawsuit that she had known Walker since May of that year and they dated "from time to time." She also knew Irvin because he lived with Walker. On the night of Nov. 9, 1997, she met up with Walker, Irvin, Billups, and Mercer at a Boston comedy club, and she was part of a group of men and women who all were hanging out there that night. When the evening ended, Irvin told her to get into a car with Billups, which she did, and Billups drove her, Mercer, and Irvin to Walker's home, where she was assaulted in Irvin's room. Doe said that she tried to stop the assault "but found she was not strong enough to protect herself from her assailants." Doe said she could not fully recall what happened because she was unconscious for part of the night, but some moments she did recall.

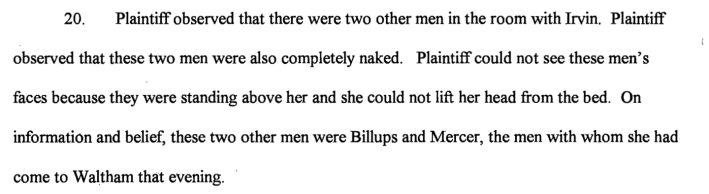

She recalled Irvin "gripped her head tightly with both of his hands while forcing his penis into her mouth" in his bedroom while he was naked. She recalled gagging. She also said there were two other men in the room.

At one point, Doe said that she recalled Walker appearing in the room, dressed only in gym shorts. According to the complaint, Irvin said to Walker, "Don't you want some?" Walker said he did not want to have sex with the plaintiff because "I just got through with someone in the next room."

Doe said she lost consciousness and when she woke up, she was still in Irvin's bedroom, naked, with Irvin asleep next to her, and used condoms and their wrappers strewn all over the floor. She rushed out of the room and called a friend, saying "something bad" had happened to her. She found Dennis Smith, another man who she said had been at the comedy club, who was asleep in the basement. Smith went upstairs, then told her that Walker wanted to talk to her before she left. She said no to that and "pleaded with Smith to take her home," which he did. While driving, Smith tried to talk to her about what happened, but Doe didn't want to. Doe said she was "trembling and crying uncontrollably," so much she could not eat the food that Smith had bought her. Smith told her not to "tell" about what had happened.

(Doe does not used the term gang rape in the complaint, but her lawyers do use that later in the case, once, when they are fighting the motions to dismiss from Mercer and Billups. On June 19, they wrote, "In her Amended Complaint, the plaintiff alleges that she was the victim of a gang rape in November 1997 in Waltham, Massachusetts.")

After she got home, Doe said in her complaint that was vomiting and felt severe pain in "her back, rectum, legs, neck and throat." She could not eat or drink, and she could not stop trembling or crying. Later that day, she went to Boston Medical Center. She said in her amended complaint that the exam found bruises on her body as well as injuries to her throat, cervix, and rectum. The injuries to her back "were consistent with the plaintiff having been dragged across a rug." Per her complaint, she was diagnosed with shock.

A rape kit was done and photographs were taken of her injuries. Sperm were retrieved, but at that time it was not yet established if the sperm were from Mercer, Irvin, or Billups. That same day, according to her complaint, she went to the police.

Doe's amended complaint also presents what she said Mercer, Irvin, and Billups told Waltham police. According to the document, Mercer told police that she wanted to have oral sex with him, and the oral sex happened at his home, not Walker's. Her complaint said that Billups told police that she voluntarily had oral sex with him that night as well and it happened at Mercer's home. Her complaint said that Irvin told police he had "sexual relations" with Doe that night and it too was consensual and it happened at Mercer's home. "He told police authorities that plaintiff wanted 'more sex' at Walker's home," the complaint said, "but that he, Irvin, was too tired, and therefore he went to sleep."

Doe sued Billups, Mercer, and Irvin for emotional and physical distress. She said the three men "acted with malice based upon the plaintiff's gender" and should be liable for the assault as well. She sued Walker for doing nothing to protect her in his home. While normally I wouldn't bother with the details of precisely which law a person cites in a lawsuit, it matters in this case, because Doe sued the men under the then-new Violence Against Women Act. VAWA is best known as the federal legislation that criminalized domestic violence, but it also included at the time a provision meant to make it easier for people who were victims of a crime of violence motivated by gender to sue for civil damages in federal court. That provision would soon be challenged by people who said it was an overreach by Congress beyond its powers and, therefore, should be deemed unconstitutional. And into this debate about congressional power and what the government can and cannot do to prevent gender-based violence came Doe's lawsuit.

Doe's first complaint is signed by two attorneys: Margaret A. Burnham, who already had been the first black woman judge in Massachusetts and at the time was working in private practice focusing on civil rights and international human rights, and Geraldine S. Hines, who would go on to become the first black woman to serve on the Massachusetts top court. Burnham also would go on to be one of the lawyers who helped bring the civil lawsuit against Franklin County, Mississippi, for how the county's law enforcement aided and abetted the Ku Klux Klan's murder of two young black men, Charles Moore and Henry Dee. And on June 5, a notice to the court from Doe's legal team said that Charles J. Ogletree, a legendary Harvard law professor who represented Anita Hill when she said future Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas sexually harassed her, would be participating in the case.

The same day Doe's lawyers filed her lawsuit, they also filed a motion asking for her lawsuit to be impounded, because "the nature of these claims and the notoriety of these defendants requires the plaintiff's complaint be treated other than in the ordinary course." A week later, on April 23, lawyers for all the parties filed a joint motion asking for the entire record to be impounded. U.S. District Judge Richard. G. Stearns allowed it except for docket item No. 4, which was the motion itself requesting the impounding. (Impounding is not exactly the same as sealing, but they do have the same effect for the public, which is barring us from seeing court records.)

Walker, who was represented by lawyer Nicholas Theodorou, was the first person to file a motion to dismiss on May 14. His memorandum said that, even if what happened were "assumed to be true," he had no duty to protect Doe because it was not him who asked her to go to the Waltham home and it was not his room where she said she was assaulted. Walker said he had no relationship with her that would trigger a duty to protect, and he could not have anticipated that this would happen to her.

A few days later Mercer, through lawyer Dennis J. Kelly, who previously represented former Celtic Charles Smith in his vehicular homicide trial, filed his motion to dismiss. "The clear intent of the plaintiff's actions is to blackmail Mercer into making a quick monetary settlement with her when he did nothing wrong," it read. In fact, Mercer planned to "contest this matter vigorously" and pursue his own claims against Doe for "among other things, abusing the process." It added that her claim under VAWA should be dismissed, "because that legislation is unconstitutional." In June, Irvin asked to join Mercer's request to dismiss, which was allowed.

Billups would not file his motion to dismiss until June 19, when he filed a request asking to join in and adopt Mercer's motion, essentially saying his argument was the same. His motion called Doe's allegations "outrageous." He, like Mercer, would be represented by Kelly. The motion was allowed by the court.

From that point, the case in many ways became intertwined with the ongoing legal debates about VAWA. According to court records, Doe's lawyers told the judge that in May they had called and asked one of Mercer's lawyers for more time to respond to their argument that the law was unconstitutional so that the U.S. Department of Justice could consider weighing in. Mercer's lawyer, Kelly, said no and then asked the court to deny Doe's lawyers more time because, among several reasons, "plaintiff filed this action in the anonymous name of Jane Doe, under seal, and should not be permitted to take advantage of court-ordered secrecy, on the one hand, and publication when it suits her purpose, on the other hand."

The response went on to hit upon a recurring theme in the defense for Billups, Mercer, and Walker: Doe was ruining their reputations.

"The Defendants' good characters are falsely maligned and unfairly tarnished merely by the filing of such unfounded scurrilous allegations as are made in the original complaint and the contradictory Amended Complaint," argued the opposition to Doe's motion to disclose. "Thus they chose to advocate continued sealing of the proceedings in this action. Yet unilateral disclosure of the nature and particulars of this action by the plaintiff's attorney, even to the Department of Justice, is inconsistent with the purposes of impoundment of the record. In a very real sense plaintiff seeks 'to have it both ways,' exclusively for her benefit."

Walker and Irvin filed papers to join in and adopt Mercer's request to not allow Doe's lawyers to disclose the case. Doe's lawyers argued in response that "the order sealing and impounding cannot reasonably be interpreted to prevent the parties from taking all necessary steps to marshal the legal resources needed to defend their positions, including discussing actions with, and disclosing the proceedings to other attorneys." Stearns allowed it but the notes on the document add, "This motion should have been filed before any disclosure was made. The court will not tolerate any further breaches of the sealing order."

On June 15, Walker's lawyers filed a brief in support of his motion to dismiss and reiterated his argument that he had no obligation to protect Doe. A few days later, Doe's legal team asked the court to lift the sealing and impounding orders, or to at least revise them, because the secrecy around whom they could talk to was hurting her case. Her lawyers wanted to keep her as Doe, but they wished to to seek help from the justice department as well as people with expertise on the the law, and they had not anticipated that the impounding order would stop them from getting the necessary resources. Plus, with a key part of the defense being that VAWA was illegal, her lawyers wrote, "Plaintiff should not be required to defend an Act of Congress in secret." Attorneys for all the men file court documents opposing this, arguing that the file had been sealed off at the request of Doe's lawyers and her legal team should be more than enough help for her. Doe's request was denied. There are no notes in the court file saying why.

The next battle would be over the process of discovery, the part of a case where each side discloses to the other the evidence and information it has. As part of this process, Doe sent questions to all the defendants. She requested documents from them. And she sent a subpoena for documents to then-Celtics head coach Rick Pitino, as well as a notice that she would like to take his deposition. Lawyers for all four men asked the court to delay Doe's discovery process because "Doe's discovery requests, even at this early stage of the case, are clearly focused on damages, thus revealing her true motivations, namely to blackmail the defendants into making a quick monetary settlement." The motion is so certain that Doe just wants to blackmail the men that it says so, again, to close out the document, saying Doe wants "to blackmail them into submission." It was denied.

Doe's lawyers responded by telling the court in a motion saying that the idea Doe was just fishing for money was "absurd" and that "these statements make clear that these defendants do not take these allegations seriously, and fully expect to avoid ever having to answer for their conduct."

On July 28, lawyers for all four men responded with their own request for the the court to place a protective order over discovery. The request listed a few reasons: the ongoing investigation by Waltham police and the Middlesex County District Attorney's Office, the defendants taking issue with some of Doe's questions, and media coverage of the case hurt the men's reputations.

Doe's lawyers responded with their own document, saying the request for a protective order was little more than an attempt to delay and obstruct the discovery process. It called the proposed protective order "over-inclusive and cumbersome" and said it was not the "least restrictive means of preventing harm to the parties." The response also took issue with the lawyers for the men framing Doe's requests as mostly being about money

"These repeated delay tactics serve only to protect the defendants," they wrote, "and hamper the resolution of this action."

On Aug. 18, 1998, Stearns granted the men their protective order with just a few minor changes to what they wanted.

The bickering over what the men needed to turn over in discovery would continue, with Stearns largely conceding to requests from the defendants. According to a motion filed by Mercer and Billups, both of them were interviewed on Dec. 8, 1997, by Middlesex County Assistant District Attorney Judy Carroll and Waltham Det. Sgt. David McGann. Sometime afterward, their lawyers got copies of these statements. But Mercer and Billups did not want to turn over their copies of these statements to Doe. Instead, they asked the court to give the local prosecutors a chance to get a protective order over the statements to block Doe from getting them. Stearns allowed this request, unmoved by the argument from Doe's lawyers that investigative privilege was meant to protect certain information in an investigation from becoming public, which this was not about, and that any investigative privilege was waived when authorities gave the men copies of their statements.

(Documents from both sides filed on this issue also mention an ongoing state grand jury investigation in September of 1998. There is no other mention of the grand jury in the documents. Waltham police Det. Sgt. Tim King told Defector Media they would not be releasing any information regarding this case, citing a Massachusetts law that makes all reports of sexual assault or attempted sexual assault confidential.)

Though Stearns granted the request, there's no document showing prosecutors intervening to block the sharing of the statements. But Stearns also granted a request from all four men to force Doe to sit for her deposition first, before any of them, as they were concerned that Doe would use the depositions of Billups and Pitino "to educate herself and to contrive and alter her allegations further." Doe's lawyers responded with a motion asking Stearns to reconsider this because forcing her to go first "reflects adversely" on Doe's credibility.

"More importantly, it sacrifices the court's neutrality in the matter. There is no basis for granting this motion short of accepting defendant's representations about plaintiff's credibility. In due course and based on matters properly before it, this court will decide whether this matter should go to trial," they wrote. "The trial, not the pre-trial proceedings, is the proper forum for determining who speaks the truth about the events of November 10, 1997."

Stearns denied this request, but he did allow a motion by Doe to inspect Walker's home.

In late December, Doe's lawyers asked the court to compel Irvin, Billups, and Mercer to comply with their discovery requests. Lawyers for Billups respond with their own request, citing the many reasons they believed they were not taking too long, which once again included sticking to their argument that discovery was really just about Doe trying to get money or, as they put it in the language of court, "Almost all of plaintiff's discovery requests concern Billups's ability to pay punitive damages." The same document mentioned that Billups's lawyers had not heard back from prosecutors regarding the interview documents that Doe wanted, and said Billups would produce them "subject to the Protective Order previously entered herein." Mercer's legal team filed an identical request.

On this point, Stearns agreed with Doe.

Walker did win his argument to be dismissed from the case. On Dec. 18, 1998, Stearns ruled that Walker could be dismissed because, "There is no basis upon which one could, from even the most liberal reading of the Amended Complaint, conclude that Walker had any reason to foresee that Doe would be attacked by his teammates." He went on to write that the law "with rare exceptions, imposes no duty on a witness to a crime to intervene in the aid of the victim." This followed a request from Walker's lawyers a month earlier to move up the hearing on his motion because all the media attention ran the risk of damaging his reputation. This was denied.

While Doe had been fighting attempts by Mercer, Billups, and Irvin to delay turning over discovery, her lawyers also had been battling over the constitutionality of VAWA. At a Dec. 16, 1999, hearing, attorneys from the U.S. Department of Justice and the NOW Legal Defense and Education Fund both appeared to help Doe's lawyer defend the constitutionality of VAWA and, specifically, the portion allowing civil lawsuits. And on Feb. 19, 1999, Stearns rules that the lawsuit could go forward because VAWA was constitutional, writing, "While I do not pretend that the matter is without doubt, I join the overwhelming majority of district courts that have found the VAWA constitutional."

Many courts did find this section of VAWA constitutional, but not the highest court. More than a year after Stearns's ruling, the U.S. Supreme Court would rule against this portion of the law.

On March 26, 1999, Stearns denied a motion to dismiss from Mercer and Billups, citing a decision from a separate appeals court that had ruled the civil lawsuit portion of VAWA unconstitutional. That case was Brzonkala vs. Virginia Polytechnic University, later called United States vs. Morrison, in which a college student sued Virginia Tech after she reported being raped by two football players. The university, despite having a sexual-assault policy, allegedly did nothing to punish one player and set aside the punishment of the other. Years before college students would sue their universities for similar failings under Title IX—the federal civil rights law that mandates all people, regardless of sex, have equal access to education—Christy Brzonkala sued Virginia Tech under VAWA. The case would eventually go to the Supreme Court, where one of the advocates for Brzonkala's case was NOW's Julie Goldscheid, who also lent support to Doe. A year later, in 2000, the justices ruled 5-4 that the civil remedy portion of VAWA was indeed unconstitutional because violence against women, it wrote, had nothing to do with interstate commerce or equal protection, the powers Congress cited in passing the law.

"If the allegations here are true, no civilized system of justice could fail to provide her a remedy for the conduct of respondent Morrison," Chief Justice William Rehnquist wrote for the majority. "But under our federal system that remedy must be provided by the Commonwealth of Virginia, and not by the United States."

In an answer filed on March 18, 1999, Billups said he was never at Walker's home and he denied that an assault occurred. He said that Doe had oral sex with him, which she initiated, that night in a car. He also would assert a counterclaim that Doe was abusing the legal process, defaming him, and that she was ruining his endorsement deals to force him to pay her. That same day, Mercer filed his similar answers. Mercer said he too was not in Walker's home that night and that no assault happened. He denied having sex with Doe. He said that on some day—he didn't give an exact date—in November of 1997, he had consensual oral sex with Doe that she initiated at Billups's home. Mercer said he did not have any other contact with her. Like Billups, Mercer accused Doe of abusing the legal process, defaming him, and messing with his endorsement deals to force him to give her money. Doe responded to their counterclaims by denying them.

Irvin's answers to Doe's lawsuit were filed on April 14, 1999. He denied that any assault occurred.

On May 3, Doe's lawyers filed a motion asking the court to compel Mercer to answer some of her questions and produce documents that they were avoiding. Stearns allowed it. Later that month, a deadline was set for all discovery to be done by Nov. 30. And then a week later, on May 28, a document was filed saying that Doe and her lawyers were considering "alternative dispute resolution."

On June 7, lawyers for Mercer and Billups asked for six more days to respond to discovery and questions because, among the reasons given, the end of the NBA season meant there were vacations and business trips that "caused minor logistical impediments." It was allowed.

In October, what would seem like a minor turn of the legal system ended up putting the lawsuit back in the news. On Oct. 4, 1999, an appeals court vacated the dismissal of the claim against Walker, saying Stearns had ruled too soon, and sent it back, essentially saying that Walker should be added back to the lawsuit, which he was. The decision by the appeals court was public and it mentioned a summary of Doe's lawsuit, as court opinions do, but because so little was known due to nearly everything in the file being kept from the public, this meant the two-paragraph summary was news. The Boston Globe, the Boston Herald, the Associated Press, and the Telegram & Gazette covered details of the decision.

After being added back to the lawsuit, Walker would keep fighting to get himself dismissed. He would respond by telling the court in documents that Doe was far more negligent that night than he was: "Plaintiff was guilty of negligence that was greater than the total amount of negligence attributable to the defendants and, accordingly, the Complaint should be dismissed." If Doe prevailed, he believed that Mercer, Irvin, and Billups should have to contribute to any judgment he had to pay.

But adding Walker back to the lawsuit also triggered a decision from Stearns in regard to the public record. Because of the details mentioned in the appeals court opinion as well as an opinion authored by Stearns, the judge said that all the sealing and impounding of records was no longer necessary. He issued his short explanation on Dec. 9, 1999.

A day later, Doe, Mercer, and Billups all filed a motion to dismiss with prejudice because Doe, Mercer, and Billups "have settled the claims and counterclaims between them."

But Walker, Mercer, and Billups wouldn't concede to making the entire case file public. Walker asked the court to keep documents under seal because his portion of the lawsuit was ongoing, and he was concerned about Doe's "scandalous allegations." He even argued that keeping the file sealed was a matter of equity: "As Doe successfully sought permission to file her complaint under the name 'Jane Doe,' she has been able to escape all public scrutiny while at the same time subjecting defendants to these scandalous accusations. Equity, therefore, demands that the pleadings continue to be sealed in order to prevent the further dissemination of Doe's defamatory allegations." Billups and Mercer joined in this argument three days later.

On Jan. 4, 2000, Stearns ruled that the file would stay sealed in light of the objections from Walker, Billups, and Mercer and the lack of a response from Doe. But all future documents would be sealed on a case-by-case basis. Six days later, the Herald filed a motion to intervene asking that the records be unsealed. Because so little had been made public, the Herald's motion relied on what they knew from the few public opinions written by judges and reading the line item descriptions of each document on the docket. Walker then filed a motion against the Herald's request. Mercer, Billups, and Irvin joined it.

Stearns would rule for the Herald. He wrote, "The court is not persuaded that any potential harm to the defendants' reputations arising from the unsealing of the documents outweighs the presumption of public access to judicial records."

But there are still files under seal. Before everything could be made public, Walker submitted a list of documents he would like to remain under seal, which Mercer and Billups agreed to and Stearns permitted. That means there are six files you still cannot see. In his ruling, Stearns does not say why he agreed to keep those documents under seal.

Stearns ruled on Jan. 27, 2000, that all the documents, except those six selections, would become public. A few days later, stories ran in the Herald and the Globe about what they revealed. It's here that the times in which all this took place, the late 1990s and early 2000s, reveal themselves. The headline for the story published in the Herald on Feb. 3, according to the copy stored in the database LexisNexis, is, "Walker claims false charges cost him endorsements." The first sentence reads, "Celtics captain Antoine Walker claims he lost lucrative endorsements after a woman wrongfully accused him of letting his friend and teammates rape her at his Waltham condo." And the headline for the Globe? "Celtics' Walker: Accuser Sought Money." This is the first sentence on the Globe story: "Boston Celtics captain Antoine Walker says a woman contacted the Celtics looking for money before filing a lawsuit alleging that she was raped inside Walker's apartment by three of his friends and he failed to stop the attack."

After that, there are no more newspaper stories, at least that I could find.

This is also about where the court file ends, at least the copy that I received. My documents end on Jan. 27, 2000, with the Stearns order making the documents public. But there are still documents listed on the public docket, about nine by my count. I got my copy of the case file from the National Archives and Records Administration. When I asked about the pages I didn't receive, I was told that the archive gave me everything they had and my question was better directed to the U.S. District Court of Massachusetts. I contacted them and they confirmed there were missing pages from the court file. Best I can tell, using only the online docket, a stipulation of confidentiality is put in place in late February, then Doe and Walker filed a joint motion to dismiss on March 6, and on March 17 the case was closed. There's nothing on the online docket saying how the claim against Irvin was resolved.

The lawsuit and the police investigation, soon after 2000, slid into obscurity. No criminal charges were ever filed. I had never even heard of it until Billups got the Blazers job and I started seeing people talk about it on social media. But all the references I saw on social media generally used the same few sources, a handful of stories from that era that somehow survived online and a few pages from a book. How could so little be known about a case that involved three NBA players, and two accused of sexual assault? At first I thought it must have been because the documents were squirreled away, hidden from public view. But that wasn't the case at all. It was just because a woman saying she was sexually assaulted by famous men wasn't deemed terribly important news. And when the Blazers put on their press conference—so perfectly coordinated, so ready to blow past any uncomfortable questions, so certain that nothing out there could refute the team's preferred narrative—they surely wish it had stayed that way.

Update (6:02 p.m. ET): Blazers vice president of basketball communications Jim Taylor responded to Defector Media's request for comment by saying, "We do not have anything additional to share."