A story changes simply by dint of The New York Times covering it, and how the Times covers it will go a decently long way in deciding what kind of story it will become. That is something that the people in charge of the Times surely know, and no doubt take some pride in, but don't really acknowledge. If it is in the personal and professional interest of an ambitious reactionary activist like Christopher Rufo to make his means and ends seem transparent and intentional, it is in the interest of the Times to make all of that work and all of those considerations invisible; the activist wants to appear more in control of the situation than he actually is, and the institution wants its role to recede. For an institution that deals in objectivity, the idea is to act as if that role doesn't even exist.

It's that last bit, the pretense of a perspective that is above and immune to the viral noise and chaos of The Discourse, that makes talking about the Times so unpleasant. Accept it, and there's nothing to talk about; deny it and you will find yourself talking much faster and more heatedly than you ordinarily would like to think of yourself as talking. Go off about how the Times is beholden to a smug, musty liberalism it can't acknowledge, or about how it primarily serves to translate the ravenous imperatives of all-consuming capitalism into something less tonally alarming, and you will be ... mostly right both times, actually, but also asking the wrong questions and making yourself somebody that people won't really want to talk to. This is not just because complaining about the Times is what political scientists call "Hannity Coded," or even just because it's tiresome. It's because most of what's wrong here, and so much of what keeps those wrong things wrong, is less about what the Times actually believes and more about how the Times sees and doesn't see its own broader hand in things. This is all pretty unbearable, so it makes sense that Harvard University, a hyper-online billionaire, and the U.S. House of Representatives would all be involved in the story that has most recently brought it to the fore.

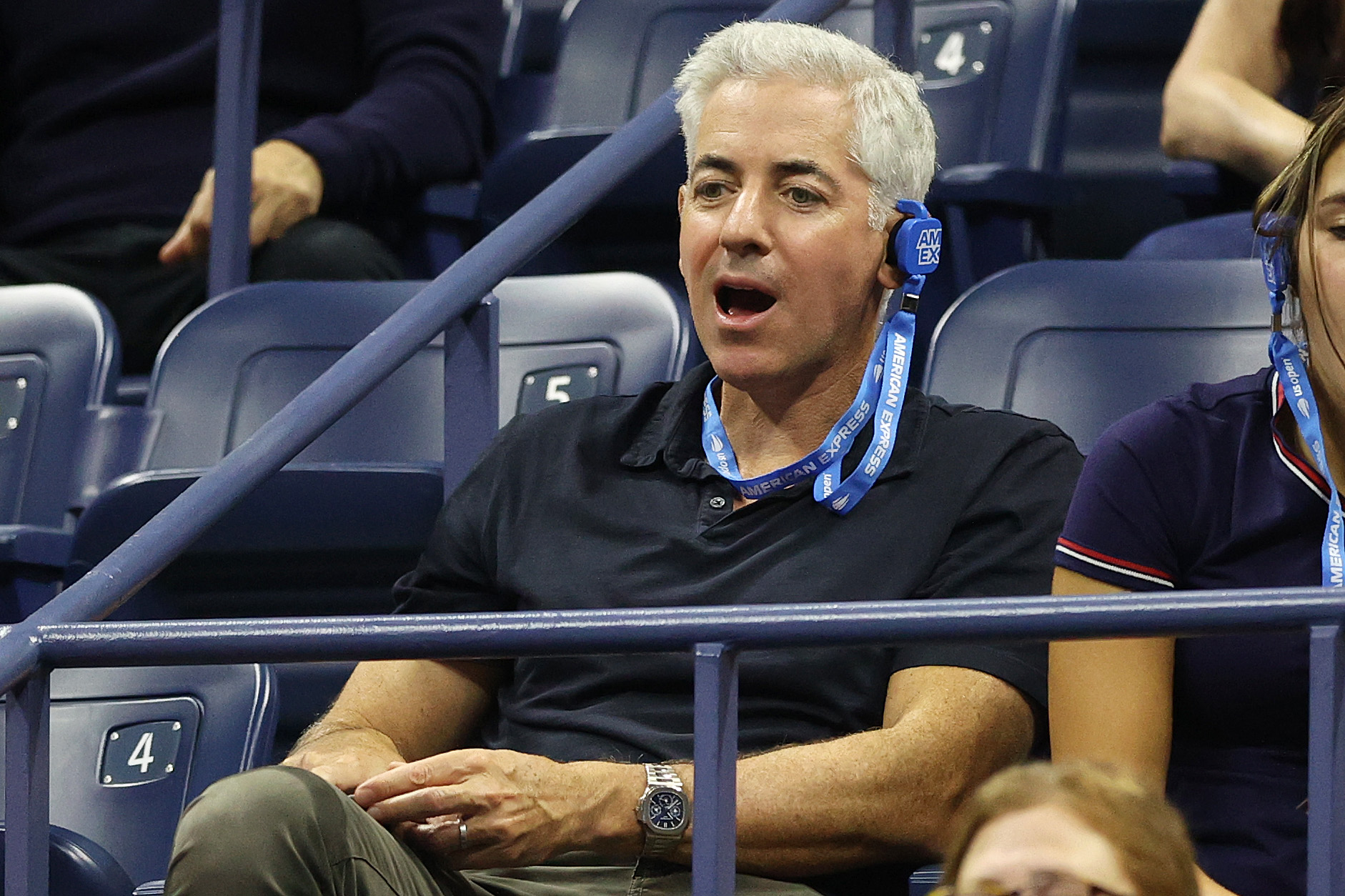

As quickly as possible: Harvard's president, Claudine Gay, resigned one week ago, after a pressure campaign against her by wealthy donors. The justification for the campaign changed in the ways that such reasons tend to over time. Gay's fumbling attempt at a good-faith answer to some deliriously bad-faith questions by Rep. Elise Stefanik (Harvard '06) about her administration's approach to antisemitic speech on campus was the proximate cause, at least until a campaign led by Rufo painting Gay as a serial plagiarist ushered her past scholarship into its place. Gay is the first black person and second woman to be president of Harvard, which allowed those interested in doing so to make her the avatar of an out-of-control [long pause] diversity. Donors like Bill Ackman (Harvard '88, Harvard Business School '92), the aforementioned poignantly online hedge fund dip, got mad and stayed mad; various rich people got upset with each other, and with the other rich people on Harvard's board of trustees.

"The board members had received plenty of advice and criticism by others in their wealthy circles, Harvard alumni, and donors," the Times reported in one of the dozens of stories they wrote about all this. "But when they arrived at their vacation spots around Christmas they were besieged by a new wave from friends and relatives." Eventually the board, which the Times noted included among other alumni "an heir to the Tootsie Roll fortune," made it clear that they simply could not go on, getting harangued like this, at their respective vacation spots. Gay would have to resign.

"SCAPLED," Rufo tweeted triumphantly. Ackman first got mad that the Massachusetts Institute of Technology had not fired its president for her (different, better) answers to Stefanik in Congress—the Times, to date, has run two stories about this woman remaining in her job—and then got angrier still when Business Insider revealed last week that Ackman's wife, a high-profile former MIT professor, had engaged in much more egregious acts of plagiarism than Gay. He has been posting about it ever since, revealing in the process that this has been especially unpleasant for his wife because she is an introvert, and that the orb his wife sent to Jeffrey Epstein in thanks for a large donation was in fact a completely normal thing, and also that Brad Pitt was interested in his wife but nothing came of it. As is the custom among his tranche of amphetamized rich guys, Ackman has done this in a series of very long tweets written in a tone that might be described as "Rorshach from Watchmen being interviewed on CNBC."

Is any of this interesting to you? The answer will depend on how interesting you find the braying drawing-room dramas of rich dullards, and also how patient you are with being lied to by people dumber than you. The world-historic fatuity of the people running the country's most powerful institutions and pouting grandiosely atop its most egregious piles of treasure phases in and out of urgency without ever ceasing to be palpable; their dreary personal defects and cheesy clubhouse feuds had cast a long and dispiriting shadow over the broader culture long before Donald Trump imposed his own collection first onto and then over national politics.

Whatever is going on at Harvard, because it is happening at Harvard, will always matter a great deal to people like these. This is how you wind up with coverage like the kind that the Times has lavished on this story; the Times reporter Anemona Hartocollis (Harvard '77), who heads the paper's "have you heard about what they're doing at Skylar's college" beat, said in an interview with her own paper that said coverage "mobilized a cast of more than a dozen reporters with different areas of expertise from the business, politics, culture and education teams" to tell this story. She also said that it's "been exhausting since early October," which is not a statement I'm prepared to argue with in the least.

On the merits, this is all pretty familiar, pretty embarrassing stuff. It is one of the oldest and least-inspiring American stories, in which a mediocre and self-regarding elite unfolds its dull anxieties and off-the-rack bigotries outwards and upwards until they assume the size and shape of a worldview. These are not very interesting people on balance, nor have they ever had to concern themselves with more important things, and so their anxieties are boring and small. They're afraid of losing their advantages, but also about being seen as more like what they are and less like the Olympians they play in a culture that worships power as a default, and its most garish and unaccountable expressions as a sort of degrading fandom.

That anxiety scales effectively up and down the country's hierarchy of aspirational tyrants; there's the billionaire hedge fund guy alternately thundering away like Cobra Commander and whinging about how unfair everyone is being to him and his wonderful wife, and also there's the managing partner from Hyundai of St. Augustine rooting him on in the replies. It is difficult to put into words how dull this all is, or the dissociative vertigo of feeling the broader culture tilting backwards at the unnatural angle of a sinking cruise ship under the weight of the dreary prank wars and feuds and high-handed busybody bullshit of America's richest and most readily flustered people. The euphemisms cooked up by activists like Rufo and advanced by sweaty congressional nullities and the twitchy super-class of activist capitalists are insulting in their flimsiness. It would not necessarily be better if everyone involved said what they really meant when they bluster about DEI or CRT or whatever other ominous acronymic way of saying "black people in positions of authority," but we would save some time.

But if every single visible aspect of this story has been unappealing and insulting in its particulars, it's worth sparing a moment of consideration for the invisible aspect. The double-bylined Times blow-by-blow of Gay's last days as Harvard's president, after a rundown of various incidents—Ackman tweeting some things that were true and some other things that weren't, those uncomfortable conversations about the alma mater in Turks & Caicos—notes that "newspaper articles about Dr. Gay and the board kept coming."

That is less a passive or exonerative construction than an admission of where and how the Times sees its role in all this—as the invisible hand of respectable opinion, a tidal force that carries things forward or back. To be fair, the paper will also write stories about how diversity as a concept and corporate practice are overwhelmingly popular, and about how virtually none of the dire implications of those antisemitism hearings were grounded in observable reality, and about how all that deep concern about antisemitism has already been abandoned by Congresspeople and activists alike in favor of a more open-ended campaign against older targets. The coverage is honest in that way, but crucially less so about the bigger question of how all of this vapor and gossip and recursive rich-guy umbrage became a story in the first place.

It would be foolish and exhausting to speculate on the role that Times editor-in-chief Joseph Kahn (Harvard '87, Harvard M.A. '90) played in pushing this story; there is nothing to do but speculate, there. Power works in different ways, and if Ackman–style public meltdowns are the loudest and most overt expression of that work, and Rufo's store-brand Rasputin act are the most obviously motivated, they are not the only ones. There is also the Times' understanding of itself as the author of the discourse, and all that ostentatious invisibility—the decisions about what is and is not a story, or what is and is not up for debate, that only show up in the negative.

You already know how that works; we are soaking in it. Someone at the institution decides that there is or ought to be, say, a debate about the safety or advisability of trans health care where no such debate actually exists, and then the debate is manufactured to suit that sense—in and through stories about that debate. And then, at some point down the line, some laws are promulgated that reflect that debate's terms.

When Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine banned trans health care in his state last week, he did not do it by signing a heavy-handed law passed through his state's legislature. He vetoed that, and then effectively did the same thing in a way that reflected all the deep and vexing complexities and risks that the Times has repeatedly insisted exist. He mandated a process that would force people seeking that care to navigate a series of onerous administrative requirements, and to compel the services of an endocrinologist, and a bioethicist, and a mental health specialist—to make sure that care is not given too fast. "It needs to be lengthy," DeWine said of the counseling component, "and it needs to be comprehensive."

So what begins as irresponsible, ideological, but plausibly deniable discourse shows up down the line as policy. It's rarely quite as easy to see as it is in this instance, when irresponsible, ideological, plausibly deniable discourse is the policy. The debate can only ever continue; the resolution will arrive without any visible fingerprints, as a story about something that just happened.