When Paul Henderson scored the series-winning goal at the 1972 Summit Series, all of Canada rejoiced. And then they exhaled.

The eight-game clash between Canada, the nation that invented ice hockey and whose top pros exclusively populated NHL rosters, and the Soviet Union, the nation that dominated amateur hockey at the Olympics and the world championships, was the first opportunity for the world’s best players to collide on the ice. What was expected to be a Canadian cakewalk turned into an embarrassing fiasco as the Soviets, backstopped by 20-year-old Vladislav Tretiak, jumped out to a 3-1-1 edge, with the final three contests to be held in Moscow.

Only, the USSR couldn’t stop Henderson, who qualified for national sainthood by tallying game-winning goals in each of those three games, the last one coming with just 34 seconds remaining in Game 8. Canadians of a certain age remember exactly where they were on September 28, 1972, when announcer Foster Hewitt exulted, “Henderson has scored for Canada!” Wayne Gretzky, all of 11 years old, was jumping up and down in front of his family’s TV set in Brantford, Ontario, having skipped school to watch the game.

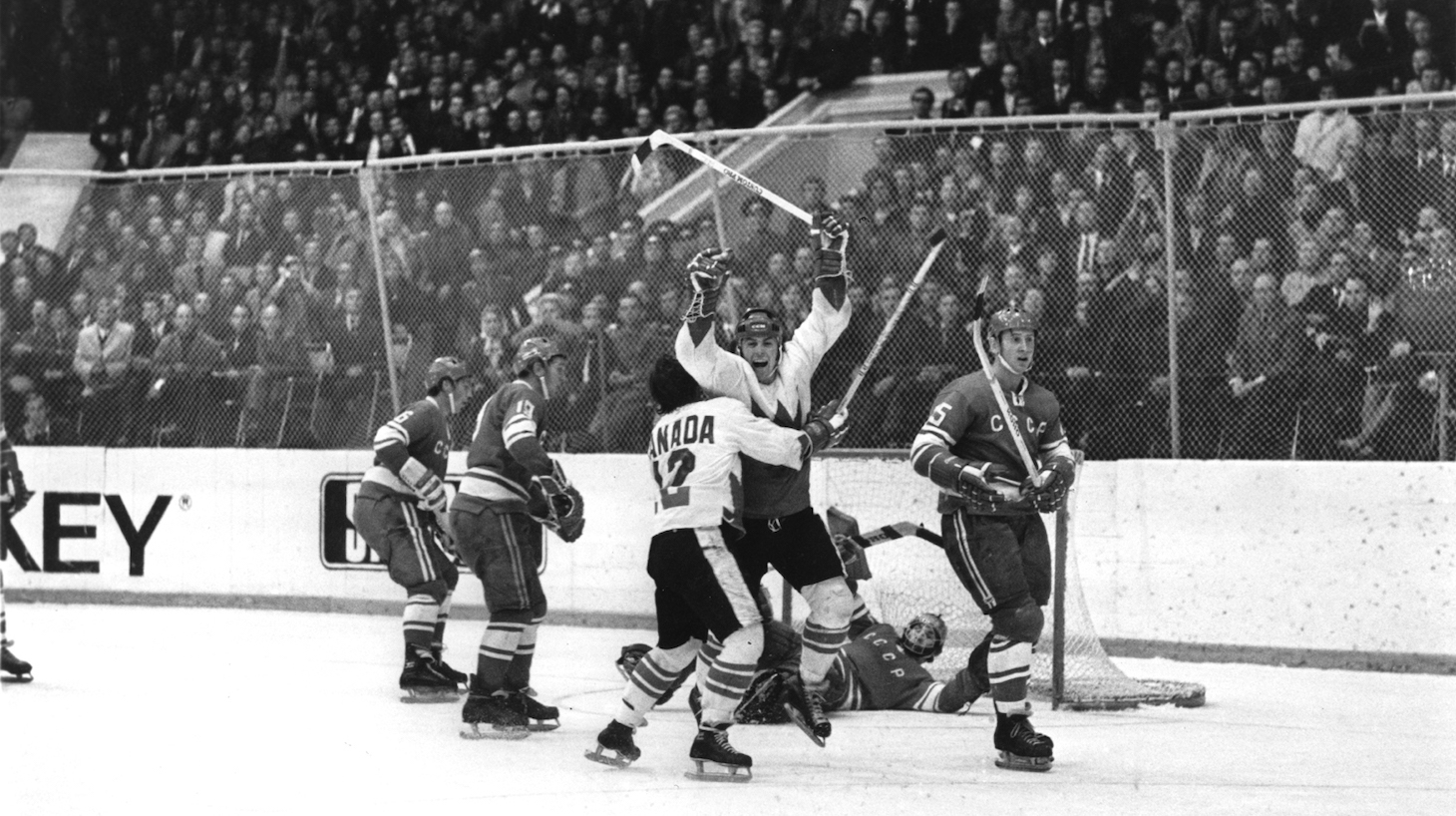

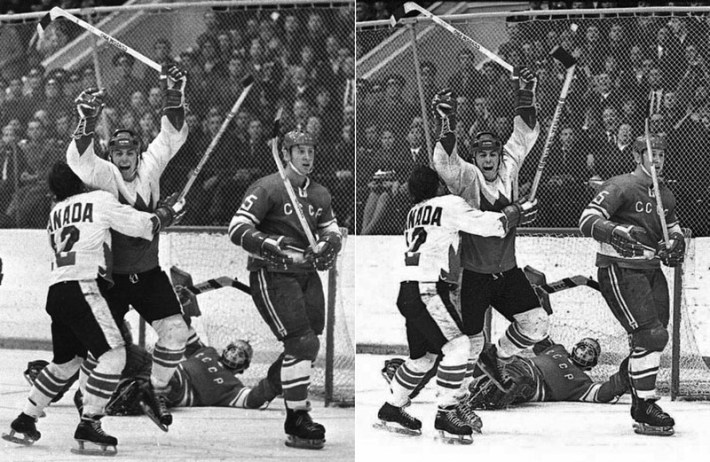

What imprinted the moment forever in Canada’s psyche is the indelible image of Henderson celebrating in the arms of teammate Yvan Cournoyer, a fallen Tretiak in the background. The black-and-white image resonated not only because it captured the joy (and relief) of victory, but also because two photojournalists took nearly identical pictures of the climactic moment. The pictures are so similar that Frank Lennon and Denis Brodeur were likely standing shoulder to shoulder when they aimed their Nikon cameras at Henderson and produced twin timeless images.

Before Moscow, Lennon and Brodeur crossed paths occasionally at hockey arenas. Lennon was born into newspapers. His father and an uncle worked at the Toronto Star, the largest newspaper in Canada (and where Ernest Hemingway gained experience as a reporter before turning to novels). Frank started as a messenger boy in 1944. He graduated to the post of darkroom technician and, to learn how to shoot quality pictures under pressure, moonlighted as a wedding and birthday-party photographer.

According to his son, Kevin, Frank Lennon was one of the first staff photographers hired by the Star. He kept a police radio in his car and shot breaking news, crime, entertainment, politics, and sports, photographing everyone from Pierre and Margaret Trudeau to Cher to Leonard Cohen to Marcel Duchamp to Warren Moon to Cito Gaston—and everyone from Gordie Howe to Bobby Hull to Bobby Orr to Wayne Gretzky. He frequented Maple Leaf Gardens so often that his position inside the arena, at ice level to the right of the net the Leafs shot on in the first and third periods, was dubbed “Frank’s corner.”

Denis Brodeur was known for his hockey skills before he took up photography. Small and nimble, the Montreal native turned down a professional contract with the AHL’s Cleveland Barons so that he could represent Canada at the 1956 Winter Olympics. The diminutive goalkeeper met heartbreak at the open-air rink in Cortina d’Ampezzo, beaten by the U.S. team that took silver behind the Soviet Union’s first hockey gold. Brodeur and Canada settled for the bronze.

After hanging up his goalkeeper’s pads, Brodeur turned to photography full-time. He started with a Rolleiflex twin-lens camera and a hand-held flash before graduating to a Hasselblad and then a Nikon. He freelanced for Montréal-Matin, a French-language tabloid, and showed his dedication to the craft by bolting strobe lights into the ceiling of the Montreal Forum. He soon became the Canadiens’ team photographer and later served in the same post with the Expos after they began play in 1969. Every year he’d pack his family into the car and drive to spring training in Florida.

The two journalists, hailing from different cultures within Canada, were friendly rivals when it came to photography. But when it came to facing off against the USSR, they united behind Canada, just as every one of their countrymen did. Indeed, roiling beneath the ice was the realpolitik of the Cold War. Sporting events were viewed as a way for world powers to establish (or deepen) diplomatic relations—or reflect real-world tensions. In the span of a few weeks that summer, American chess prodigy Bobby Fischer outwitted his Russian opponent, Boris Spassky, at the World Championship in Reykjavik, and the men’s basketball final between the U.S. and the USSR at the Munich Olympics ended in a controversial decision that is still debated today. Meanwhile, exhibition table-tennis matches involving American and Chinese “ping pong diplomats” were keying rapprochement between the two nations.

The Summit Series was détente on skates, but it was also a battle for global bragging rights.

The amateur-only rule in international hockey prevented NHL pros from competing head-to-head against the USSR national team (not to mention the highly regarded squads from Czechoslovakia and Sweden). Canada’s hockey powerbrokers argued that the Soviets were skirting the rules by slotting talented athletes into state-subsidized jobs (often in the military) that enabled them to train and compete full-time while maintaining “shamateur” status. In protest, Canada dropped out of the Olympics and the world championships, hockey’s two most prestigious international competitions.

Finally, led by notorious lawyer-agent Alan Eagleson, the two nations brokered a deal for an eight-game exhibition series before the 1972–73 NHL season. Four games in Canada, four games in Russia, 480 minutes to settle the score; the pros against the amateurs, the maple leaf versus the hammer and sickle, capitalism against communism, democracy against totalitarianism, the individual versus the collective. It was, as a later documentary would dub it, the Cold War on Ice.

Team Canada packed its roster with 35 of the NHL’s top players. Phil Esposito had just led the Boston Bruins to their second Stanley Cup title in three years; he was joined by high-flying Yvan Cournoyer, Stan Mikita, the Mahovlich brothers, the Rangers’ GAG (goal-a-game) line of Hadfield-Ratelle-Gilbert, and defensemen Brad Park, Guy Lapointe, and Serge Savard. In goal were Phil’s brother Tony and the cerebral Ken Dryden, who would backstop Montreal to six Stanley Cups. Foster Hewitt, the beloved voice of Hockey Night in Canada, came out of retirement to give the play-by-play for the TV broadcasts.

However, Team Canada entered the series without several key figures. Bruins defenseman Bobby Orr had scored the championship-clinching goal in the 1972 Stanley Cup Finals while sweeping the regular season, All-Star Game and playoff MVP awards, but was unavailable after surgery on his fragile left knee. Bobby Hull, Gerry Cheevers, Derek Sanderson, and J. C. Tremblay were banned because they’d signed contracts to play in the rival WHA. Gordie Howe had retired after the 1970–71 season.

Team Canada faced other obstacles. Many of the players hadn’t skated since April; they were in “summer-cottage shape,” according to writer-musician Dave Bidini, and accustomed to getting into game shape during training camp. They only had time to practice together for 18 days before the opening face-off. Essentially, they were a group of overconfident, flabby stars with little-to-no experience playing together.

The selection of Paul Henderson to the team received scant notice even though the speedy left winger was coming off his most productive season with the Maple Leafs, scoring 38 goals. Coach Harry Sinden put him on a line centered by the Flyers’ Bobby Clarke with Toronto teammate Ron Ellis on the other wing.

One piece of equipment made Henderson instantly identifiable on the ice: his ubiquitous red helmet. After being concussed while playing for the Red Wings, he was forced to wear protective headgear. He was practically the only NHLer to use one in those less-scientific times, but with CCM paying him to wear the gear, he stuck with it.

Facing Canada was a team that, since joining the Olympic Movement after World War II, dominated amateur hockey. The USSR had just swept to their third consecutive gold medal at the 1972 Sapporo Olympics; they’d racked up nine consecutive world championships before losing to Czechoslovakia that spring. Skilled, cohesive, and supremely well-conditioned, their creative passing and transition play unleashed a flowing, dynamic style that upended the dump-chase-and-check model of the stodgy NHL.

Still, as the birthplace of hockey, Team Canada was expected to easily dispatch the Soviets. “The N.H.L. team will slaughter them in eight straight,” predicted New York Times reporter Gerald Eskenazi. Globe and Mail columnist Dick Beddoes opined, “If the Russians win one game, I will eat this column shredded at high noon in a bowl of borscht on the front steps of the Russian embassy.”

The day after Bobby Fischer was crowned chess champion, ending a 24-year reign for Soviet grandmasters, hockey fans streamed into the Montreal Forum for Game 1 of what one writer called the “Super Bowlski.” Ever the political opportunist, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau dropped the ceremonial first puck. Esposito scored almost immediately and then Henderson scored to give Team Canada a 2-0 lead less than seven minutes into the first period.

The rout was on right up until the unexpected happened. The Soviets weren’t fazed by the early goals or the Forum crowd and, with relentless skating, soon flummoxed the NHL’s best. They tied the score, 2-2, with a short-handed goal before the end of the first period and cruised to a 7-3 victory that was not even as close as the final score indicated.

Insult was added to injury: the exhausted players from Team Canada stumbled to their locker room unaware that, according to protocol, they were supposed to line up and shake hands with the Soviets after the game. Poor sportsmanship was added to a long list of miscues.

A shocked, devastated nation grasped at excuses and wallowed in self-doubt over what the Star labeled “hockey humiliation.” Beddoes, a man of his word, posed for photographers at the Soviet consulate in Toronto and, yes, ate his column. The previously unfamiliar names of the visitors—Tretiak, the high-scoring forward Valeri Kharlamov, coach Vsevolod Bobrov—haunted the dreams of every Canadian.

Team Canada re-grouped in Game 2 with a 4-1 win in Toronto as Tony Esposito replaced Dryden in goal. The terrorist attack at the Munich Olympics stole the world’s attention before Game 3 in Winnipeg; that evening, while the locals seethed about the absence of Bobby Hull, the original (and Golden) Jet, the USSR rallied from a two-goal deficit for a hard-fought 4-4 draw.

The final game in Canada ended in resounding defeat for the locals after two power-play goals by Boris Mikhailov gave the Soviets a 2-1-1 series edge. Spectators at Vancouver’s Pacific Coliseum lustily booed the NHLers when they exited the ice, prompting Phil Esposito to scold them in his post-game TV interview.

“To the people across Canada, we tried our best,” he said, sweat dripping down his face. “For the people that boo us, geez ... all of the guys are really disheartened and we’re disillusioned and we’re disappointed in some of the people. We cannot believe the bad press we’ve got, the booing we’ve gotten in our own buildings. ... I don’t think it’s fair that we should be booed.”

The carefree arrogance that characterized Canada’s attitude before the series started had disintegrated. Forget détente: Now it was “war,” Esposito declared.

Team Canada stopped off in Stockholm to play the Swedish national team and get used to Europe’s larger rinks. Some 3,000 Canadian die-hards accompanied them abroad, paying upward of $650 (or about $4,200 CAD today) for a tour package that included round-trip airfare, tickets to the four games in Moscow, and rooms at the Rossiya, then the largest hotel in the world.

The Star sent Frank Lennon to cover the scene behind the Iron Curtain. He took pictures at the Kremlin and St. Basil’s Cathedral; he shot the players in street clothes as they roamed the city with their wives and handed out gum to children, and the rowdy fans as they chanted “Da Da Canada, Nyet, Nyet Soviet.”

Denis Brodeur almost didn’t make the trip. He and his wife, Mireille, had just had their fifth child, a son they named Martin—you’ve probably heard of him. But Denis traveled to Moscow on his own dime because he and sportswriter Gilles Terroux were collaborating on a book about the series and, as he later told journalist Dave Stubbs, he picked up some work from other clients.

The interior lighting at Moscow’s Luzhniki Palace of Sports was poor, but the layout favored photographers, according to Melchior DiGiacomo, who shot the series for Sports Illustrated. No plexiglass barriers were mounted along the boards behind each goal—just wire netting—and there was plenty of space for them to roam, despite the presence of armed soldiers. “We could practically walk from one end of the ice to the other along this passageway [in front of the first row of seats],” DiGiacomo said in an interview. “Nobody gave us any hassle.”

Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev was prominently seated in the presidential box as Team Canada jumped out to an early 3-0 lead in Game 5. Then, disaster struck for the visitors. After Henderson misfired on a shot, he fell to the ice and crashed into the boards in an awkward position. He was concussed, but his helmet probably saved him from serious, even permanent injury. He returned to the ice and, on his next shift, scored for Canada. But the home team didn’t wilt, netting four consecutive goals for a 5-4 victory and 3-1-1 series lead.

The defeat was “the best thing” to happen to Team Canada, Henderson later said, because now they began to play “like cornered rats.”

Actually, they went goony. Late in the second period of Game 6, Bobby Clarke swung his stick like a baseball bat and broke the left ankle of star forward Kharlamov. The Soviets took the early lead, but three consecutive goals by Canada—the last by Henderson—gave the visitors the victory, 3-2.

Henderson saved the day again in Game 7. With less than three minutes remaining, the score knotted at 3-3, Henderson took a pass at center ice surrounded by four Soviets. He somehow pushed the puck through defenseman Gennady Tsygankov, then beat Tretiak over his right shoulder for the improbable winner. He called it “the most satisfying goal I ever scored in my life.”

Two days later was Game 8, to decide the 3-3-1 series. The teams traded power-play goals in the first period, before the Soviets took a 5-3 lead into the third. Esposito and Cournoyer scored to even the score with seven minutes remaining in the game. (The organizers of the Series had decreed no overtime.)

Frank Lennon was shooting in the rafters, but with the game tied he returned to ice level. He stationed himself to Tretiak’s left, between the blue line and the goal, near where he’d shot a captivating photo of Henderson’s game-winner from Game 7. He was using a Nikon F camera.

Denis Brodeur had left this same area to shoot photos of the Soviet coach. When Canada tied the score, he scurried back and loaded a fresh roll of black-and-white Kodak film into his own Nikon F, with a 135mm lens and a motor-drive.

Less than a minute to play. Canada, desperate, fought to keep the puck in the Soviet zone. Henderson came on for Peter Mahovlich, joining Esposito and Cournoyer, and he immediately darted toward the USSR net as Cournoyer held the puck along the boards to the left of Tretiak.

Cournoyer sent the puck cross-ice toward the streaking Henderson, but the pass was broken up and Henderson crashed into the boards behind the net. The Soviets couldn’t clear, and Esposito alertly whacked the loose puck toward Tretiak from inside the faceoff circle as Henderson, up on his skates, dashed to the front of the net, defenders looming.

Foster Hewitt called it for TV viewers back home:

“… Cournoyer has it on that wing! Here’s a shot! Henderson made a wild stab for it and fell! Here’s another shot! Right in front! THEY SCORE! Henderson has scored for Canada! Henderson right in front of the net! And the fans and the team are going wild! Henderson right in front of the Soviet goal with 34 seconds left in the game! An absolute mob scene over Paul Henderson as there should be and this crowd is going wild!”

For Lennon and Brodeur, preparation met the moment. They concentrated on getting the shot, on chronicling history, as time simultaneously sped up and slowed down: Here’s Henderson trying to corral the rebound from Esposito’s shot: Click! Click! Here’s Henderson stabbing at the puck again and somehow flipping it over Tretiak: Click! Click! Here’s Henderson, stick raised high in glee as Cournoyer embraces him and forlorn defenseman Yuri Liapkin stares at a lifetime of ignominy: Click! Click! Here’s the entire team, including Dryden skating the length of the ice, mobbing Henderson: Click! Click! And, here’s the scoreboard: Канада 6, CCCP 5. Click!

The war was over, but the photographers’ work was just beginning. On deadline, Lennon hurriedly developed the film in his hotel room. Then he transmitted his pictures over the wire, from Moscow to London to New York to Toronto. The next day, his photo of Henderson embracing Cournoyer was splashed across five columns on the front page of the Star and then re-printed in papers across the country. The tightly cropped version—viewed full-frame, it’s actually a horizontal—was the first to be seen by the world and the version most Canadians conjure up when they hear the name “Paul Henderson.”

“Everybody around him jumped up and Frank would [later] say to me that he was amazed he had the presence of mind to keep shooting,” said Henderson, who befriended Lennon afterwards. “Everything within him wanted to jump up and shout.”

Lennon won the National Newspaper Award for Best News Photo, and was named Canadian photographer of the year. In 2008, The Beaver (now Canada’s History magazine) named it one of the “10 photos that changed Canada.”

Brodeur, meanwhile, rushed over to the news offices of Izvestia to develop his film. He wasn’t on deadline, but he wanted to see if he had The Shot. He did, and more: a 17-frame sequence that captured the goal and the celebration. He was fortunate, he later said to Dave Stubbs, because the last two pictures were actually the 37th and 38th frames on a 36-exposure roll of film. Brodeur’s photos were published in the book he co-authored with Gilles Terroux, entitled Face-off of the Century: Canada-U.S.S.R., as well as in numerous books and magazines.

This was not the first time that two or more photographers produced nearly identical pictures of an epic moment. Nat Fein was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for his portrait of Babe Ruth at his Yankee Stadium farewell, a touching moment that the Associated Press’s Harry Harris also captured. Neil Leifer’s exquisitely framed color photo of Muhammad Ali standing over Sonny Liston during their second heavyweight championship bout has been called the “best sports photo of the century,” while the AP’s John Rooney’s strikingly similar photo (albeit in black and white) is rarely recognized. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette staffer Morris Berman took a dramatic picture of Giants quarterback Y. A. Tittle after he was knocked senseless in a 1964 game; Berman’s picture hung in the Pro Football Hall of Fame, while comparable photos taken by the AP’s Dozier Mobley and Pittsburgh Press’s Don Stetzer are overlooked.

Fate was fickle for other photographers in Moscow. Mel DiGiacomo had a prized lens smashed during the series. He missed the goal, but did manage a tight shot of Esposito hugging Henderson and Cournoyer. Brian Pickell, on assignment to shoot the official commemorative book, was alternating among three cameras before he ran out of film in each of them in the closing minute. He was inserting film when Henderson scored.

Back home, demand for reprints of Lennon’s photo swamped the syndication desk at the Star. The newspaper ceded the negative to him, and he began churning out prints for a ravenous public.

In 1990, Lennon retired after close to 50 years with the Star. He was given ownership of his most famous photo, and he eventually copyrighted the image. The “Goal of the Century” has been licensed for countless books, posters, trading cards, a Royal Canadian Mint coin, even a postage stamp. After his death in 2006, his family donated Lennon’s entire oeuvre, some 123,400 photos, to Library and Archives Canada in Ottawa, while retaining ownership of the Henderson photo.

In 2010, Denis Brodeur auctioned off the 17-frame series of the Henderson goal for nearly $50,000. (Henderson’s sweater from the series sold for $1.275 million.) According to published reports, Brodeur also sold his collection of more than 100,000 photos, which included his other pictures from the Summit Series, to the NHL for $350,000.

By then, Brodeur was more famous for being Martin’s father than for his photography. Denis traveled to the Salt Lake City Olympics in 2002 to witness his son the goaltender lead Canada to the gold medal, the country’s first since 1952, and, in 2010, he watched as Martin and Canada won Olympic gold on home ice in Vancouver. He died in 2013.

Paul Henderson has spent nearly every day since 1972 listening to strangers tell him where they were when he scored The Goal. He struggled to live up to his legend, he later acknowledged. He feuded with Maple Leafs owner Harold Ballard and signed a lucrative contract to jump to the Toronto Toros of the WHA. (This qualified him to play in the 1974 Summit Series, featuring the Soviets against WHA players, which the Soviets won, 4-1-3.) When the Toros relocated to Birmingham, Alabama, he helped introduce professional ice hockey to the South. Henderson ended his unique career—and, really, is there any other in sports comparable to his?—playing minor-league hockey.

Younger Canadians have their own generational landmark moments: the Gretzky-to-Lemieux game-winner over the Soviets at the 1987 Canada Cup; Joe Carter’s walk-off homer at the 1993 World Series; Sidney Crosby’s “golden goal” over Team USA at the Vancouver Olympics; Jose Bautista’s bat flip to decide the 2015 ALDS; Kawhi Leonard's four-bounce buzzer-beater en route to a 2019 Raptors title.

But the Henderson goal endures, buttressed by an endless torrent of thinkpieces, books, dissertations, documentaries, poems, and songs that have dissected and explicated its significance for Canada and the NHL. The slight differences between Frank Lennon’s iconic photograph of Paul Henderson and Denis Brodeur’s iconic photograph of Paul Henderson matter less with each passing year. It’s as if they’ve merged into one grainy apparition of jubilation, pride, patriotism, and relief.

Acknowledgements: Besides my own interviews and newspaper and magazine research from 1972 to the present, I consulted several books for this story, including Roy MacSkimming’s Cold War: The Amazing Canada-Soviet Hockey Series of 1972; Ken Dryden’s Face-Off at the Summit (written with Mark Mulvoy, photos by Mel DiGiacomo); Ken Dryden and Roy MacGregor’s Home Game: Hockey and Life in Canada; Paul Henderson’s How Hockey Explains Canada (written with Jim Prime); Gary Ronberg’s The Ice Men; Dave Bidini’s A Wild Stab For It: This Is Game Eight From Russia (with photos by Brian Pickell); Sean Mitton and Jim Prime’s The Goal That United Canada; and Brodeur and Terroux’s Face-Off of the Century: Canada-U.S.S.R. Also, Dave Stubbs has written several enlightening articles about Denis Brodeur and his photography career. Two documentaries about the series were helpful: Cold War on Ice (George Roy dir., NBC Sports) and Summit On Ice (CBC).