In 2019, Björn Persson snapped a photo of Tim, a famous Kenyan elephant, standing against a dark and cloudy sky. The dramatic photo won Persson the title of Photographer of the Year in a contest run by the travel company African Geographic. But after the award was announced, people who were familiar with Tim—he was, after all, a famous elephant—noticed the unique rips and tears on his ears were missing. The contest's judges disqualified Persson when they realized he had digitally manipulated the photo, and gave the top prize to a picture of a jumping spider instead.

Tim's airbrushed ears are far from the most egregious act of deception in wildlife photography, a field that is famous for forgery. It's challenging to photograph wild animals in the wild, so some photographers cut corners: snapping headshots on game farms, baiting elusive subjects like owls, and even dabbling in animal cruelty by gluing or freezing insects. Pretty much any photo you see of a frog "riding" another animal, such as a turtle or beetle, is the product of staging. So wildlife photography contests have strict ethical standards, and eagle-eyed judges are experienced at spotting manipulated photos. In 2018, a photo of an anteater investigating a bioluminescent termite mound under a starry sky, which won a Wildlife Photography of the Year award administered by the Natural History Museum in London, was withdrawn after judges noticed the anteater was almost certainly taxidermied. In 2010, a photographer was stripped of the same award after judges determined his photo of a dramatically jumping Iberian wolf had been staged a photo using a tame wolf from a wildlife park.

These recent, high-profile scandals in photo editing caught the interest of a group of researchers in the United Kingdom and Australia, who recently published a paper in the journal People and Nature investigating the effects that digital touch-ups can have on our perceptions of and care for endangered species. They wondered: Would people be more willing to give conservation money to a beautiful, airbrushed bird than its real-life counterpart? "Photography has been so widely used by conservation NGOs," said Diogo Gaspar Veríssimo, a conservation researcher at the University of Oxford and an author on the paper. "At the same time we know that humans on fashion magazines and other outlets are definitely retouched sometimes beyond reason," he added.

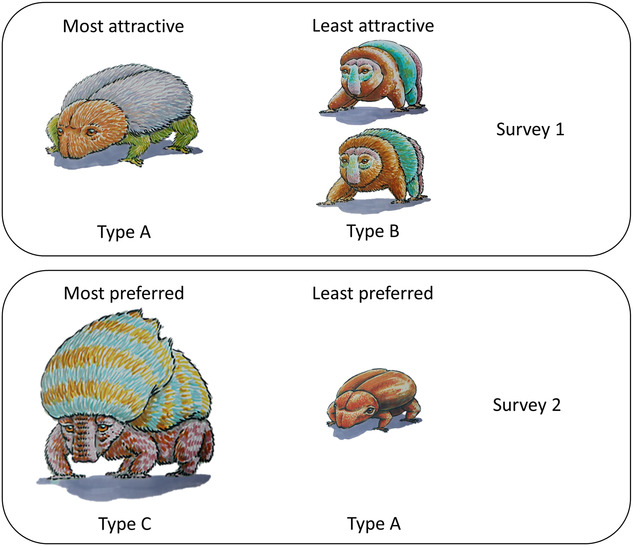

For humans and animals, being born beautiful, at least by human standards, can be a gift and a curse. The aesthetic appeal of turtles and tropical fish make them targets of poaching. But an animal's beauty also influences how much we are willing to invest in their survival. To many, a world without snow leopards might seem a tragedy. A world without common slit-faced bats might seem less tragic. And a world without tapeworms might even seem preferable. So animals like pandas and penguins take center stage in conservation, starring in ad campaigns and the logos of nonprofits, while slimier, scaled species wait in the wings for attention, and funding, that may never come. A paper published in 2020 in Conservation Letters previously put this idea to the test. The researchers created a series of imaginary animals of various sizes, shapes, colors, and textures, and asked participants to rank their animals from most to least attractive. Unsurprisingly, people preferred larger, more colorful imaginary animals—the charismatic megafauna of the paper—and indicated they were more likely to donate towards the beauties of the bunch.

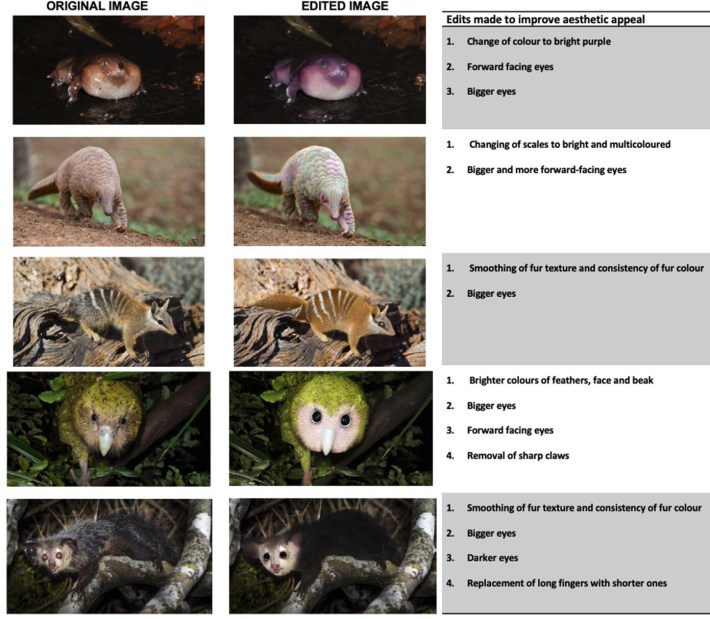

The authors of the new paper wanted to extend this research into the realm of real species. They selected five species: the striped marsupial called the numbat, the purple-colored pignose frog, the Indian pangolin, the long-fingered lemur called the aye-aye, and the world's only flightless parrot, the kākāpō. The researchers chose these species because they were relevant to the NGO funding the paper, and represented a spectrum of appearances, Veríssimo said. The researchers then worked with an image editing organization to make photos of each of these species more "appealing" by standards suggested by prior research, including the 2020 paper. The editing made them more colorful; increased the size of their eyes; reduced irregularities in their fur or feathers; even downplayed some of their more unsavory features, such as the unsettlingly long fingers of the aye-aye. In other words, they yassified them.

Survey participants were then asked how they would allocate £5,000 among three choices: a classically charismatic animal like an elephant, an uncharismatic species like the Hispaniolan solenodon, a shrew-like creature with a hairless snout, and either an edited or unedited version of one of the five species in the study. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the researchers found people funneled more of their hypothetical donations to the yassified animals than their dowdy real-life counterparts. "I was surprised that this effect was detectable with this group of species not only because they are already relatively charismatic but also because our sample was relatively limited in size," Veríssimo said.

The researchers also gathered three focus groups to gauge their reactions to both original and unedited images. When asked what words they would use to describe each image, and the reasons they felt that way, several focus groups did not mince words. After seeing original, unedited photos of several species, the focus groups found the aye-aye "freaky and weird," the numbat "skinny and coarse," the kākāpō "dirty," and the pig-nosed frog "slimy and horrible." Fortunately, no focus group had a bad word to say about the pangolin, either in its muted original form or Lisa Frank–like makeover.

When presented with the edited images, the participants were drawn to the strange, sultry eyes of the yassified pig-nosed frog. "Yeah the cartoonish features and the clear facial expression looks like a child throwing a strop," said one participant, referring to what appears to be the British equivalent of a temper tantrum. But many were hung up on the extreme face-tuning of the kākāpō. "It just doesn't look real at all," said one participant, adding "the shape of the face was just too perfect." This suggests that photos that have been too obviously manipulated might sow distrust in viewers. After all, people are less likely to send conservation money toward animals that appear not to be endangered but rather to be Webkinz.

As Veríssimo pointed out, the study focused on species that are already quite charismatic. Pangolins are essentially walking pinecones, aye-ayes offer representation to all the gothy freaks, and a bright green, chunky bird that waddles around the forests of New Zealand has charm to spare. It is unclear how the paper's image-editing practices might apply to far less charismatic endangered species, but Veríssimo says that looking to invertebrates or plants would be the next step. How, exactly, does one yassify an abalone? Would people find a colorful medicinal leech or furry American burying beetle more or less appealing? I may disagree with the idea that a hot little Facetuned leech should garner more conservation dollars than the drab blood-suckers of the real world, but I personally would love to see one. Seriously, if you have Photoshop and some free time, please email your hot abalones, Kawaii leeches, and glamorous beetles to simbler@defector.com.